Religion in the Public Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptation Strategies of Islamist Movements April 2017 Contents

POMEPS STUDIES 26 islam in a changing middle east Adaptation Strategies of Islamist Movements April 2017 Contents Understanding repression-adaptation nexus in Islamist movements . 4 Khalil al-Anani, Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, Qatar Why Exclusion and Repression of Moderate Islamists Will Be Counterproductive . 8 Jillian Schwedler, Hunter College, CUNY Islamists After the “Arab Spring”: What’s the Right Research Question and Comparison Group, and Why Does It Matter? . 12 Elizabeth R. Nugent, Princeton University The Islamist voter base during the Arab Spring: More ideology than protest? . .. 16 Eva Wegner, University College Dublin When Islamist Parties (and Women) Govern: Strategy, Authenticity and Women’s Representation . 21 Lindsay J. Benstead, Portland State University Exit, Voice, and Loyalty Under the Islamic State . 26 Mara Revkin, Yale University and Ariel I. Ahram, Virginia Tech The Muslim Brotherhood Between Party and Movement . 31 Steven Brooke, The University of Louisville A Government of the Opposition: How Moroccan Islamists’ Dual Role Contributes to their Electoral Success . 34 Quinn Mecham, Brigham Young University The Cost of Inclusion: Ennahda and Tunisia’s Political Transition . 39 Monica Marks, University of Oxford Regime Islam, State Islam, and Political Islam: The Past and Future Contest . 43 Nathan J. Brown, George Washington University Middle East regimes are using ‘moderate’ Islam to stay in power . 47 Annelle Sheline, George Washington University Reckoning with a Fractured Islamist Landscape in Yemen . 49 Stacey Philbrick Yadav, Hobart and William Smith Colleges The Lumpers and the Splitters: Two very different policy approaches on dealing with Islamism . 54 Marc Lynch, George Washington University The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network that aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . -

Or C\^Iing Party. \

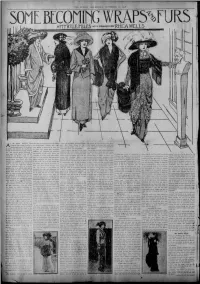

r 3 the season advances one's that they are their own excuse for being— This type is prettily developed In mole- the dismay of those observers who dislike thoughts turn toward evening en- as reconstructed emeralds and ruMes skin. Mrs. Frank Nelson, Jr., has a their fidgety movements and would fain scarf and big pillow muff of this fur enjoy the classic calm of the unbeplum- tertainments, and it is the toilette have gained a distinction of their own do soiree and de theatre that which she wears very becomingly. aged bandeau. manteau by their real beauty and excellence. There is also a scarf of tlie black One of the quaintest coiffure ornaments occupy the attention of the lady of fash- big Moreover, fur imitations are absolutely fur In Mr. Wells’ sketch. It is fitted in town is black velvet and ion. The evening gowns mentioned in lynx bright green if the sisters and I Indispensable wives, about the neck and at one end Is orna- tulle. It Is clasped in the back with a these pages from time to time and de- of something to give in celebration of Many families hold the bridal veil as one popular colors in what is known as tho daughters of others than multi-million- a of made in the mented with handsome sil£ frog, pro- narrow' hand of mother pearl, very scribed by pen pictures Christman has begun to crowd the shops. of the most precious of heirlooms, to b© “made*’ veils and these with their well aires are to be with ducing that “one-sided” effect at once thin and very lustrous. -

The Construction of National Culture and Identity in a Province: the Case of the People's House of Kayseri

THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY FULYA BALKAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA AND CULTURAL STUDIES DECEMBER 2019 i ii Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Lütfi Doğan Tılıç (Başkent Uni., HIT) Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan (METU, ADM) Assoc. Prof. Barış Çakmur (METU, ADM) iii ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Fulya Balkar Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI Balkar, Fulya M.S., Department of Media and Cultural Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan December 2019, 249 pages This thesis focuses on the Kayseri House experience in early republican period and aims to explore how the narratives of national culture and identity were constructed in a so-called conservative province in the context of the Kayseri House. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

The Role of Religion in Public Life and Official Pressure to Participate in Alcoholics Anonymous, 65 U

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Summer 1997 The Role of Religion in Public Life and Official essurPr e to Participate in Alcoholics Anonymous Paul E. Salamanca University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Paul E. Salamanca, The Role of Religion in Public Life and Official Pressure to Participate in Alcoholics Anonymous, 65 U. Cin. L. Rev. 1093 (1997). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Religion in Public Life and Official essurPr e to Participate in Alcoholics Anonymous Notes/Citation Information University of Cincinnati Law Review, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Summer 1997), pp. 1093-1168 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/412 THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN PUBLIC LIFE AND OFFICIAL PRESSURE TO PARTICIPATE IN ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS Paul E. Salamanca* [F]or an hour it was deadly dull, and I was fidgety. Miss Watson would say, "Dont put your feet up there, Huckleberry;" and "dont scrunch up like that, Huckleberry-set up straight;" and pretty soon she would say, "Don't gap and stretch like that, Huckleberry-why don't you try to behave?" Then she told me all about the bad place, and I said I wished I was there. -

Constitutionalizing Secularism, Alternative

This article is published in a peer‐reviewed section of the Utrecht Law Review Constitutionalizing secularism, alternative secularisms or liberal-democratic constitutionalism? A critical reading of some Turkish, ECtHR and Indian Supreme Court cases on ‘secularism’ Veit Bader* 1. Introduction Recently, the heated debates on secularism in social sciences, politics and, increasingly, in political theory and political philosophy have also infected legal theory, constitutional law and comparative constitutionalism. Generally speaking, it may indeed be ‘too late to ban the word “secular”’ or to remove ‘secularism’ from our cultural vocabulary. The argument, however, that ‘too many controversies have already been stated in these terms’1 seems unconvincing to me. For the purposes of normative theory generally, and particularly for those of constitutional law and jurisprudence, the focus of this article, I have proposed to replace all normative concepts of ‘secularism’ by ‘priority for liberal-democracy’2 because I am convinced that we are better able to economize our moral disagreements or to resolve the substantive constitutional, legal, jurisprudential and institutional issues and controversies by avoiding to restate them in terms of ‘secularism’ or ‘alternative secularisms’. With regard to the ‘constitutional status of secularism’ we can discern three distinct positions all sharing the argument that ‘secularism (...) in most liberal democracies (…) is not explicitly recognized in the constitutional text or jurisprudence’3 and that it has ‘no clear standing * Professor Emeritus of Social and Political Philosophy (Faculty of Humanities) and of Sociology (Faculty of Social Sciences) at the University of Amsterdam (the Netherlands), email: [email protected] Thanks for critical comments and suggestions to Christian Moe, Ahmet Akgündüs, Yolande Jansen, Bas Schotel, Gunes Tezcur, Asli Bali, Werner Menski, an anonymous reviewer and the participants of conferences in New Delhi, Utrecht, and Istanbul where I presented earlier versions of this article. -

Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokã¡R Prohã¡Szka

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 12 Issue 3 Article 6 6-1992 Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokár Prohászka Leslie A. Muray Lansing Community College, Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Muray, Leslie A. (1992) "Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokár Prohászka," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol12/iss3/6 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I ; MODERNISM AND CHRISTIAN SOCIALISM IN THE THOUGHT OF OTTOKAR PROHASZKA By Leslie A. Moray Dr. Leslie A. Muray (Episcopalian) is professor of religious studies at the Lansing Community College in Lansing, Michigan. He obtained his Ph.D. degree from the Graduate Theological School in Claremont, California. Several of his previous articles were published in OPREE. Little known in the West is the life and work of the Hungarian Ottokar Prohaszka (1858- 1927), Roman Catholic Bishop of Szekesfehervar and a university professor who was immensely popular and influential in Hungary at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. He was the symbol of modernism, for which three of his works were condemned, and Christian Socialism in his native land. -

"Religion-Neutral" Jurisprudence: an Examination of Its Meaning and End

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 13 (2004-2005) Issue 3 Article 5 February 2005 "Religion-Neutral" Jurisprudence: An Examination of Its Meaning and End L. Scott Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Religion Law Commons Repository Citation L. Scott Smith, "Religion-Neutral" Jurisprudence: An Examination of Its Meaning and End, 13 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 841 (2005), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol13/iss3/5 Copyright c 2005 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj "RELIGION-NEUTRAL" JURISPRUDENCE: AN EXAMINATION OF ITS MEANINGS AND END L. Scott Smith* INTRODUCTION The United States Supreme Court has in recent years, more than ever before, rested its jurisprudence of religion largely upon the notion of neutrality. The free exercise of religion, the Court has asserted, does not guarantee a person the right, based upon religious observance, to violate a law that is religiously neutral and of general applicability.' The nonestablishment norm of the Constitution is accordingly * M.Div., Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary; Ph.D., Columbia University; J.D., Texas Tech University. This Article is dedicated to Professors Kenneth Benson, Brick Johnstone, and Jill Raitt, with whom I enjoyed many inspiring conversations while I was a senior fellow in law at the University of Missouri's Center for Religion, the Professions, and the Public, from January through May, 2004. ' Employment Div. v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990). Michael W. McConnell correctly predicted in 1992 that, since Smith, with its emphasis upon neutrality, represented the Court's position on the Free Exercise Clause, "it is to be expected that the Court will soon reinterpret the Establishment Clause in a manner consistent with Smith." Michael W. -

An Embellishment: Purdah

An Embellishment: Purdah For An Embellishment: Purdah,i a two-part text installation for an exhibition, Spatial Imagination (2006), I selected twelve short extracts from ‘To Miss the Desert’ and rewrote them as ‘scenes’ of equal length, laid out in the catalogue as a grid, three squares wide by four high, to match the twelve panes of glass in the west-facing window of the gallery looking onto the street. Here, across the glass, I repeatedly wrote the word ‘purdah’ in black kohl in the script of Afghanistan’s official languages – Dari and Pashto.ii The term purdah means curtain in Persian and describes the cultural practice of separating and hiding women through clothing and architecture – veils, screens and walls – from the public male gaze. The fabric veil has been compared to its architectural equivalent – the mashrabiyya – an ornate wooden screen and feature of traditional North African domestic architecture, which also ‘demarcates the line between public and private space’.iii The origins of purdah, culturally, religiously and geographically, are highly debated,iv and connected to class as well as gender.v The current manifestation of this gendered spatial practice varies according to location and involves covering different combinations of hair, face, eyes and body. In Afghanistan, for example, under the Taliban, when in public, women were required to wear what has been termed a burqa, a word of Pakistani origin. In Afghanistan the full-length veil is more commonly known as the chadoree or chadari, a variation of the Persian chador, meaning tent.vi This loose garment, usually sky-blue, covers the body from head to foot. -

Colonial and Orientalist Veils

Colonial and Orientalist Veils: Associations of Islamic Female Dress in the French and Moroccan Press and Politics Loubna Bijdiguen Goldmiths College – University of London Thesis Submitted for a PhD in Media and Communications Abstract The veiled Muslimah or Muslim woman has figured as a threat in media during the past few years, especially with the increasing visibility of religious practices in both Muslim-majority and Muslim-minority contexts. Islamic dress has further become a means and technique of constructing ideas about the ‘other’. My study explores how the veil comes to embody this otherness in the contemporary print media and politics. It is an attempt to question constructions of the veil by showing how they repeat older colonial and Orientalist histories. I compare and contrast representations of the dress in Morocco and France. This research is about how Muslimat, and more particularly their Islamic attire, is portrayed in the contemporary print media and politics. My research aims to explore constructions of the dress in the contemporary Moroccan and French press and politics, and how the veil comes to acquire meanings, or veil associations, over time. I consider the veil in Orientalist, postcolonial, Muslim and Islamic feminist contexts, and constructions of the veil in Orientalist and Arab Nahda texts. I also examine Islamic dress in contemporary Moroccan and French print media and politics. While I focus on similarities and continuities, I also highlight differences in constructions of the veil. My study establishes the importance of merging and comparing histories, social contexts and geographies, and offers an opportunity to read the veil from a multivocal, multilingual, cross-historical perspective, in order to reconsider discourses of Islamic dress past and present in comparative perspective. -

The Portrayal of the Historical Muslim Female on Screen

THE PORTRAYAL OF THE HISTORICAL MUSLIM FEMALE ON SCREEN A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 SABINA SHAH SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES LIST OF CONTENTS List of Photographs................................................................................................................ 5 List of Diagrams...................................................................................................................... 7 List of Abbreviations.............................................................................................................. 8 Glossary................................................................................................................................... 9 Abstract.................................................................................................................................... 12 Declaration.............................................................................................................................. 13 Copyright Statement.............................................................................................................. 14 Acknowledgements................................................................................................................ 15 Dedication............................................................................................................................... 16 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ -

Rethinking Religious Minorities' Political Power

Rethinking Religious Minorities’ Political Power Hillel Y. Levin* This Article challenges the assumption that small religious groups enjoy little political power. Based on this assumption, the dominant view is that courts are indispensable for protecting religious minority groups from oppression by the majority. But this assumption fails to account for the many and varied ways in which the majoritarian branches have chosen to protect and accommodate even unpopular religious minority groups, as well as the courts’ failures to do so. The Article offers a public choice analysis to account for the surprising majoritarian reality of religious accommodationism. Further, it explores the important implications of this reality for deeply contested legal doctrines, as well as the insights it offers for recent and looming high- profile cases pitting state law against religious liberty. * Copyright © 2015 Hillel Y. Levin. The Author is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Georgia School of Law. He thanks Nelson Tebbe, Douglas Laycock, Ron Krotoszynski, James Oleske, Chip Lupu, Paul Horwitz, Michael Broyde, Nathan Chapman, Harlan Cohen, Dan Coenen, and Bo Rutledge for helping to refine — and challenge — the ideas explored in this article and their comments on earlier drafts. He is also grateful to Amelia Trotter, Andrew Mason, and Heidi Gholamhosseini for their excellent research assistance. 1617 1618 University of California, Davis [Vol. 48:1617 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: THE COUNTERMAJORITARIAN ASSUMPTION ............. 1619 I. THE MAJORITARIAN REALITY .................................................. 1627 A. Reframing the Discourse: A Tale of Two Eruvs ................ 1628 1. The Countermajoritarian Eruv: Tenafly, New Jersey ........................................................................ 1631 2. The Majoritarian Eruv: Memphis, Tennessee .......... 1635 3.