Demystifying the Catalytic Pathway of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Isocitrate Lyase Collins U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lignite Coal Burning Seam in the Remote Altai Mountains Harbors A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Lignite coal burning seam in the remote Altai Mountains harbors a hydrogen-driven thermophilic Received: 20 September 2017 Accepted: 17 April 2018 microbial community Published: xx xx xxxx Vitaly V. Kadnikov1, Andrey V. Mardanov1, Denis A. Ivasenko2, Dmitry V. Antsiferov2, Alexey V. Beletsky1, Olga V. Karnachuk2 & Nikolay V. Ravin1 Thermal ecosystems associated with underground coal combustion sites are rare and less studied than geothermal features. Here we analysed microbial communities of near-surface ground layer and bituminous substance in an open quarry heated by subsurface coal fre by metagenomic DNA sequencing. Taxonomic classifcation revealed dominance of only a few groups of Firmicutes. Near- complete genomes of three most abundant species, ‘Candidatus Carbobacillus altaicus’ AL32, Brockia lithotrophica AL31, and Hydrogenibacillus schlegelii AL33, were assembled. According to the genomic data, Ca. Carbobacillus altaicus AL32 is an aerobic heterotroph, while B. lithotrophica AL31 is a chemolithotrophic anaerobe assimilating CO2 via the Calvin cycle. H. schlegelii AL33 is an aerobe capable of both growth on organic compounds and carrying out CO2 fxation via the Calvin cycle. Phylogenetic analysis of the large subunit of RuBisCO of B. lithotrophica AL31 and H. schlegelii AL33 showed that it belongs to the type 1-E. All three Firmicutes species can gain energy from aerobic or anaerobic oxidation of molecular hydrogen, produced as a result of underground coal combustion along with other coal gases. We propose that thermophilic Firmicutes, whose spores can spread from their original geothermal habitats over long distances, are the frst colonizers of this recently formed thermal ecosystem. Studies of thermophilic microorganisms that survive and develop at temperatures that are extreme for ordi- nary life have broadened our understanding of the diversity of microorganisms and their evolution, the mech- anisms of adaptation to environmental conditions. -

Yeast Genome Gazetteer P35-65

gazetteer Metabolism 35 tRNA modification mitochondrial transport amino-acid metabolism other tRNA-transcription activities vesicular transport (Golgi network, etc.) nitrogen and sulphur metabolism mRNA synthesis peroxisomal transport nucleotide metabolism mRNA processing (splicing) vacuolar transport phosphate metabolism mRNA processing (5’-end, 3’-end processing extracellular transport carbohydrate metabolism and mRNA degradation) cellular import lipid, fatty-acid and sterol metabolism other mRNA-transcription activities other intracellular-transport activities biosynthesis of vitamins, cofactors and RNA transport prosthetic groups other transcription activities Cellular organization and biogenesis 54 ionic homeostasis organization and biogenesis of cell wall and Protein synthesis 48 plasma membrane Energy 40 ribosomal proteins organization and biogenesis of glycolysis translation (initiation,elongation and cytoskeleton gluconeogenesis termination) organization and biogenesis of endoplasmic pentose-phosphate pathway translational control reticulum and Golgi tricarboxylic-acid pathway tRNA synthetases organization and biogenesis of chromosome respiration other protein-synthesis activities structure fermentation mitochondrial organization and biogenesis metabolism of energy reserves (glycogen Protein destination 49 peroxisomal organization and biogenesis and trehalose) protein folding and stabilization endosomal organization and biogenesis other energy-generation activities protein targeting, sorting and translocation vacuolar and lysosomal -

Supporting Information High-Throughput Virtual Screening

Supporting Information High-Throughput Virtual Screening of Proteins using GRID Molecular Interaction Fields Simone Sciabola, Robert V. Stanton, James E. Mills, Maria M. Flocco, Massimo Baroni, Gabriele Cruciani, Francesca Perruccio and Jonathan S. Mason Contents Table S1 S2-S21 Figure S1 S22 * To whom correspondence should be addressed: Simone Sciabola, Pfizer Research Technology Center, Cambridge, 02139 MA, USA Phone: +1-617-551-3327; Fax: +1-617-551-3117; E-mail: [email protected] S1 Table S1. Description of the 990 proteins used as decoy for the Protein Virtual Screening analysis. PDB ID Protein family Molecule Res. (Å) 1n24 ISOMERASE (+)-BORNYL DIPHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 2.3 1g4h HYDROLASE 1,3,4,6-TETRACHLORO-1,4-CYCLOHEXADIENE HYDROLASE 1.8 1cel HYDROLASE(O-GLYCOSYL) 1,4-BETA-D-GLUCAN CELLOBIOHYDROLASE I 1.8 1vyf TRANSPORT PROTEIN 14 KDA FATTY ACID BINDING PROTEIN 1.85 1o9f PROTEIN-BINDING 14-3-3-LIKE PROTEIN C 2.7 1t1s OXIDOREDUCTASE 1-DEOXY-D-XYLULOSE 5-PHOSPHATE REDUCTOISOMERASE 2.4 1t1r OXIDOREDUCTASE 1-DEOXY-D-XYLULOSE 5-PHOSPHATE REDUCTOISOMERASE 2.3 1q0q OXIDOREDUCTASE 1-DEOXY-D-XYLULOSE 5-PHOSPHATE REDUCTOISOMERASE 1.9 1jcy LYASE 2-DEHYDRO-3-DEOXYPHOSPHOOCTONATE ALDOLASE 1.9 1fww LYASE 2-DEHYDRO-3-DEOXYPHOSPHOOCTONATE ALDOLASE 1.85 1uk7 HYDROLASE 2-HYDROXY-6-OXO-7-METHYLOCTA-2,4-DIENOATE 1.7 1v11 OXIDOREDUCTASE 2-OXOISOVALERATE DEHYDROGENASE ALPHA SUBUNIT 1.95 1x7w OXIDOREDUCTASE 2-OXOISOVALERATE DEHYDROGENASE ALPHA SUBUNIT 1.73 1d0l TRANSFERASE 35KD SOLUBLE LYTIC TRANSGLYCOSYLASE 1.97 2bt4 LYASE 3-DEHYDROQUINATE DEHYDRATASE -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information (a) (b) Figure S1. Resistant (a) and sensitive (b) gene scores plotted against subsystems involved in cell regulation. The small circles represent the individual hits and the large circles represent the mean of each subsystem. Each individual score signifies the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. The p-value was calculated as a two-tailed t-test and significance was determined using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; false discovery rate was selected to be 0.1. Plots constructed using Pathway Tools, Omics Dashboard. Figure S2. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-resistant gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S3. Connectivity map displaying the predicted functional associations between the silver-sensitive gene hits; disconnected gene hits not shown. The thicknesses of the lines indicate the degree of confidence prediction for the given interaction, based on fusion, co-occurrence, experimental and co-expression data. Figure produced using STRING (version 10.5) and a medium confidence score (approximate probability) of 0.4. Figure S4. Metabolic overview of the pathways in Escherichia coli. The pathways involved in silver-resistance are coloured according to respective normalized score. Each individual score represents the mean of 12 trials – three biological and four technical. Amino acid – upward pointing triangle, carbohydrate – square, proteins – diamond, purines – vertical ellipse, cofactor – downward pointing triangle, tRNA – tee, and other – circle. -

The TB Structural Genomics Consortium: a Resource for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Biology

ARTICLE IN PRESS Tuberculosis (2003) 83, 223–249 Tuberculosis www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/tube The TB structural genomics consortium: a resource for Mycobacterium tuberculosis biology T.C. Terwilligera,*, M.S. Parka, G.S. Waldoa, J. Berendzenb, L.-W. Hungb, C.-Y. Kima, C.V. Smithc, J.C. Sacchettinic, M. Bellinzonid, R. Bossid, E. De Rossid, A. Mattevid, A. Milanod, G. Riccardid, M. Rizzid, M.M. Robertse, A.R. Cokerf, G. Fossatig, P. Mascagnig, A.R.M. Coatese, S.P. Woodf, C.W. Gouldingh, M.I. Apostolh, D.H. Andersonh, H.S. Gillh, D.S. Eisenbergh, B. Tanejai, S. Mandei, E. Pohlj, V. Lamzinj, P. Tuckerj, M. Wilmannsj, C. Colovosj, W. Meyer-Klauckej, A.W. Munrok, K.J. McLeank, K.R. Marshallk, D. Leysk, J.K. Yangl, H.-J. Yoonl, B.I. Leel, M.G. Leel, J.E. Kwakl, B.W. Hanl, J.Y. Leel, S.-H. Baekl, S.W. Suhl, M.M. Komenm, V.L. Arcusm, E.N. Bakerm, J.S. Lottm, W. Jacobs Jr.n, T. Albero, B. Ruppp aLos Alamos National Laboratory, Bioscience Division, Mail Stop M888, Los Alamos, NM, 87545, USA bLos Alamos National Laboratory, Physics Division, Mail Stop D454, Los Alamos, NM 87545, USA cDepartment of Biochemistry and Biophysis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2128, USA dDepartment of Genetics and Microbiology, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy eMedical Microbiology, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, St. George’s Hospital Medical School, Cranmer Terrace, London SW17 0RE, UK fDivision of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Southampton, Bassett Crescent -

Impact of Solar Radiation on Gene Expression in Bacteria

Proteomes 2013, 1, 70-86; doi:10.3390/proteomes1020070 OPEN ACCESS proteomes ISSN 2227-7382 www.mdpi.com/journal/proteomes Review Impact of Solar Radiation on Gene Expression in Bacteria Sabine Matallana-Surget 1,2,* and Ruddy Wattiez 3 1 UPMC Univ Paris 06, UMR7621, Laboratoire d’Océanographie Microbienne, Observatoire Océanologique, Banyuls/mer F-66650, France 2 CNRS, UMR7621, Laboratoire d’Océanographie Microbienne, Observatoire Océanologique, Banyuls/mer F-66650, France 3 Department of Proteomics and Microbiology, Research Institute for Biosciences, Interdisciplinary Mass Spectrometry Center (CISMa), University of Mons, Mons B-7000, Belgium; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-4-68-88-73-18. Received: 2 May 2013; in revised form: 21 June 2013 / Accepted: 2 July 2013 / Published: 16 July 2013 Abstract: Microorganisms often regulate their gene expression at the level of transcription and/or translation in response to solar radiation. In this review, we present the use of both transcriptomics and proteomics to advance knowledge in the field of bacterial response to damaging radiation. Those studies pertain to diverse application areas such as fundamental microbiology, water treatment, microbial ecology and astrobiology. Even though it has been demonstrated that mRNA abundance is not always consistent with the protein regulation, we present here an exhaustive review on how bacteria regulate their gene expression at both transcription and translation levels to enable biomarkers identification and comparison of gene regulation from one bacterial species to another. Keywords: transcriptomic; proteomic; gene regulation; radiation; bacteria 1. Introduction Bacteria present a wide diversity of tolerances to damaging radiation and are the simplest model organisms for studying their response and strategies of defense in terms of gene regulation. -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

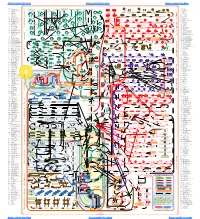

Authors: Zheng Zhao, Delft University of Technology Marcel A. van den Broek, Delft University of Technology S. Aljoscha Wahl, Delft University of Technology Wilbert H. Heijne, DSM Biotechnology Center Roel A. Bovenberg, DSM Biotechnology Center Joseph J. Heijnen, Delft University of Technology An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Marco A. van den Berg, DSM Biotechnology Center Peter J.T. Verheijen, Delft University of Technology Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. PchrCyc: Penicillium rubens Wisconsin 54-1255 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Liang Wu, DSM Biotechnology Center Walter M. van Gulik, Delft University of Technology L-quinate phosphate a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar multidrug multidrug a dicarboxylate phosphate a proteinogenic 2+ 2+ + met met nicotinate Mg Mg a cation a cation K + L-fucose L-fucose L-quinate L-quinate L-quinate ammonium UDP ammonium ammonium H O pro met amino acid a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar K oxaloacetate L-carnitine L-carnitine L-carnitine 2 phosphate quinic acid brain-specific hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical -

Polymorphic Positions in the Genome of Xcm Page 1 of 5

Polymorphic positions in the genome of Xcm seq_id position 2005 2251 4387 4389 4379 4380 4381 4383 4384 4394 4392 4395 4433 4434 genes silent/non-silent NZ_ACHT01000023 16591 G t t t t t t t t t t t t t Intergenic Intergenic NZ_ACHT01000028 7775 A c c c c c c c c c c c c c XcampmN_010100000587 ribosomal protein alanine acetyltransferase (7614-8207) non-silent tac -> taA; NZ_ACHT01000041 15615 C t t t t t t t t t t t t t XcampmN_010100000977 hemolysin III (15149-15805) non-silent atc -> aCc; NZ_ACHT01000044 2934 T c c c c c c c c c c c c c XcampmN_010100001152 hypothetical protein (2671-3549) non-silent gat -> Aat; NZ_ACHT01000044 3736 A g g g g g g g g g g g g g XcampmN_010100001157 bifunctional aspartate kinase/diaminopimelate decarboxylase non-silentprotein (3730-4207) gct -> Act; NZ_ACHT01000060 1984 C a a a a a a a a a a a a a Intergenic Intergenic NZ_ACHT01000064 1939 C t t t t t t t t t t t t t Intergenic Intergenic NZ_ACHT01000072 4507 A c c c c c c c c c c c c c XcampmN_010100002109 VirB3 protein (4240-4551) non-silent atg -> atT; NZ_ACHT01000089 30693 A c c c c c c c c c c c c c XcampmN_010100002947 hypothetical protein (30250-31116) silent atc -> atA; NZ_ACHT01000101 1035 T c c c c c c c c c c c c c XcampmN_010100003517 soluble lytic murein transglycosylase (1-1051) non-silent cgc -> cAc; NZ_ACHT01000101 2893 T c c c c c c c c c c c c c XcampmN_010100003522 TonB-dependent receptor (1308-4187) non-silent gcg -> gTg; NZ_ACHT01000120 419 A c c c c c c c c c c c c c XcampmN_010100004174 acyl carrier protein phosphodiesterase (162-746) -

Suppl Fürcorel Ohne Mend Ohnetextfelder.Cdr

Additional File 1 Fermentation stage-dependent adaptations of Bacillus licheniformis during enzyme production Sandra Wiegand, Birgit Voigt, Dirk Albrecht, Johannes Bongaerts, Stefan Evers, Michael Hecker, Rolf Daniel and Heiko Liesegang Content Figure S1 Protease production and process parameters. ........................................................................... 2 Figure S2 Proteome of the amino acid metabolism – Part I. .................................................................... 3 Figure S3 Proteome of the amino acid metabolism – Part II. ................................................................... 4 Figure S4 Amino acid transport. ............................................................................................................... 5 Figure S5 Proteome of the central carbon metabolism. ............................................................................ 7 Figure S6 Carbohydrate transport. ............................................................................................................ 8 Figure S7 Acetoin utilization operon acuABC. ....................................................................................... 10 Figure S8 Most abundant proteins. ......................................................................................................... 10 Figure S9 Lichenicidin gene cluster. ....................................................................................................... 11 Figure S10 Cell envelope stress response. ............................................................................................. -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

Mechanism-Based Inactivator of Isocitrate Lyases 1 and 2 from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

Mechanism-based inactivator of isocitrate lyases 1 and 2 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Truc V. Phama, Andrew S. Murkinb, Margaret M. Moynihanb,1, Lawrence Harrisc, Peter C. Tylerc, Nishant Shettya,d, James C. Sacchettinia,e, Hsiao-ling Huange,f, and Thomas D. Meeka,2 aDepartment of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; bDepartment of Chemistry, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York, Buffalo, NY 14260; cThe Ferrier Research Institute, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington 5046, New Zealand; dFujifilm Diosynth Biotechnologies Texas, College Station, TX 77845; eDepartment of Chemistry, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; and fAlbany Molecular Research, Inc., Albany, NY 12203 Edited by Perry Allen Frey, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, and approved June 7, 2017 (received for review May 2, 2017) Isocitrate lyase (ICL, types 1 and 2) is the first enzyme of the McFadden (16) demonstrated that the affinity label, 3-bromopyruvate glyoxylate shunt, an essential pathway for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3BP) (Fig. 1), exerted time-dependent inactivation of Escherichia (Mtb) during the persistent phase of human TB infection. Here, we coli ICL. A crystal structure of Mtb ICL1 treated with 3BP report 2-vinyl-D-isocitrate (2-VIC) as a mechanism-based inactivator revealed that Cys191 had been S-pyruvoylated (10). One could of Mtb ICL1 and ICL2. The enzyme-catalyzed retro-aldol cleavage envision synthetic analogs of D-isocitrate that bear nascent elec- of 2-VIC unmasks a Michael substrate, 2-vinylglyoxylate, which then trophilic substituents at C-2, which are unmasked only following forms a slowly reversible, covalent adduct with the thiolate form of ICL-catalyzed retro-aldol cleavage. -

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material Figure S1. Cluster analysis of the proteome profile based on qualitative data in low and high sugar conditions. Figure S2. Expression pattern of proteins under high and low sugar cultivation of Granulicella sp. WH15 a) All proteins identified in at least two out of three replicates (excluding on/off proteins). b) Only proteins with significant change t-test p=0.01. 2fold change is indicated by a red line. Figure S3. TigrFam roles of the differentially expressed proteins, excluding proteins with unknown function. Figure S4. General overview of up (red) and downregulated (blue) metabolic pathways based on KEGG analysis of proteome. Table S1. growth of strain Granulicella sp. WH15 in culture media supplemented with different carbon sources. Carbon Source Growth Pectin - Glycogen - Glucosamine - Cellulose - D-glucose + D-galactose + D-mannose + D-xylose + L-arabinose + L-rhamnose + D-galacturonic acid - Cellobiose + D-lactose + Sucrose + +=positive growth; -=No growth. Table S2. Total number of transcripts reads per sample in low and high sugar conditions. Sample ID Total Number of Reads Low sugar (1) 15,731,147 Low sugar (2) 12,624,878 Low sugar (3) 11,080,985 High sugar (1) 11,138,128 High sugar (2) 9,322,795 High sugar (3) 10,071,593 Table S3. Differentially up and down regulated transcripts in high sugar treatment. ORF Annotation Log2FC GWH15_14040 hypothetical protein 3.71 GWH15_06005 hypothetical protein 3.12 GWH15_00285 tRNA-Asn(gtt) 2.74 GWH15_06010 hypothetical protein 2.70 GWH15_14055 hypothetical protein 2.66