Mölder a (2016). Small Forest Parcels, Management Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

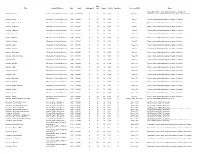

Aufstellung Haltestellen

Haltestellenübersicht VOS Süd Nr. Ort Haltestelle E/B Postleitzahl Gemeinde Zone Linie 1 Allendorf Allendorfer Straße 2 49176 Hilter 415 414 417 467 2 Allendorf Dauwe 2 49176 Hilter 415 414 417 467 3 Allendorf Ostendarp 2 49176 Hilter 415 414 417 467 4 Allendorf Pohlmann 2 49176 Hilter 415 414 417 467 5 Allendorf Zur Baumheide 2 49176 Hilter 415 414 417 467 6 Altenhagen Am Ellenberg 0 49170 Hagen 414 431 7 Altenhagen Heggestraße 0 49170 Hagen 414 430 431 8 Altenhagen Hölscher 0 49170 Hagen 414 430 463 N61 9 Altenhagen Trafo 0 49170 Hagen 414 430 431 463 N61 10 Altenhagen Zum Wöhrden 0 49170 Hagen 414 430 431 11 Aschen Alte Schule 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 12 Aschen Am Sonnenhang 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 13 Aschen B68 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 14 Aschen Brinkmann 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 422 425 15 Aschen Bahnweg 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 16 Aschen Dallhofweg 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 422 425 17 Aschen Dissener Weg 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 422 425 18 Aschen Im Dorfe 1 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 19 Aschen Firma Claas 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 20 Aschen Kamp 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 21 Aschen Karl-Wilhelm-Straße 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 22 Aschen Lindenstraße 2 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 23 Aschen Seiger 1 49201 Dissen 419 420 425 24 Aschendorf Am Landwehrbach 1 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 421 25 Aschendorf An der Grenze 2 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 421 461 26 Aschendorf An der Salzquelle 2 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 420 421 426 436 461 466 27 Aschendorf Bollweg 1 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 421 28 Aschendorf Brinkheide 1 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 421 461 29 Aschendorf Dreß 1 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 421 30 Aschendorf Hünnefeldskamp 2 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 420 421 426 436 466 31 Aschendorf Im Masch 1 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 421 32 Aschendorf Kindergarten 2 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 420 421 426 436 461 466 33 Aschendorf Kleine-Tebbe 1 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 419 421 34 Averfehrden Baumann 2 49216 Glandorf 417 433 35 Averfehrden B. -

Hasbergenbürgerbüro Der Gemeinde Hasbergen, Martin-Luther-Str

HASBERGENBürgerbüro der Gemeinde Hasbergen, Martin-Luther-Str. 12, 49205 Hasbergen HASBERGEN Bürgerbüro der Gemeinde Hasbergen vhs-Außenstelle Martin-Luther-Straße 12 49205 Hasbergen Sprechzeiten: Annelie Schmied Montag–Freitag: 8:00-12:00 Uhr Tel.: 05405 502-202 Dienstag: 14:00-16:00 Uhr Fax: 05405 502-66 Rufnummern des Bürgerbüros: Donnerstag: 14:00-19:00 Uhr E-Mail: [email protected] Tel.: 05405 502-101/-102/-103/-104 rei ausgeführt werden können. Zahlreiche Stickstiche aus der Schwälmer Weißstickerei werden auch in der Ajourstickerei POLITIK angewandt. Angefangene Arbeiten können vollendet und andere gängige Stickarten erlernt werden. Arbeitsmaterialien BERUFLICHE GESELLSCHAFT wie Stickschere, Nahttrenner, Nadeln, Leinenstoffe ect. kön- nen bei der Kursleitung erworben werden. BILDUNG UMWELT Weitere Termine: 5. Mrz. und 2. Apr. 2019 Leitung: Maria Deistler 191-130101 Ort: Hasbergen, Schule am Roten Berg, Raum B.2.2, Schulstraße 16 Bitte beachten Sie auch Wohnungseigentumsrecht Beginn: Di., 5. Feb. 2019, 18:00 Uhr unsere Angebote in der Rubrik für Anfänger/-innen Dauer: 3 Termine, mtl., je Di., 18:00-21:00 Uhr EDV/Neue Medien. Entgelt: € 30 Vortrag Weitere Informationen zu unseren Angeboten der Das Wohnungseigentumsrecht ist selbst für Eigentümer ein Beruflichen Bildung und zu den evtl. Fördermöglichkeiten Buch mit sieben Siegeln. Der Vortrag richtet sich an Eigentü- 191-130202 erhalten Sie bei mer und erläutert die Grundlagen des Wohnungseigentums- Carola Köster rechts: Was ist der Unterschied zwischen Gemeinschafts- und Das moderne Stricken Sondereigentum? Welche Rechte und Pflichten hat der Woh- und Häkeln Tel.: 0541 501-3083 nungseigentümer? Welche der Verwalter? Welche Aufgabe E-Mail: [email protected] oder bei der Verwaltungsbeirat? Wie ist eine Wohnungseigentümer- Jetzt neu: Mosaik stricken Hermann Wellers versammlung durchzuführen? Wie haben die Jahresabrech- In diesem Kurs können Sie Socken mit der Tomaten-, Bume- (Sozialpflege) nung und der Wirtschaftsplan auszusehen? rang- oder ohne Ferse stricken. -

Verzeichnis Aller Schulen Im LKOS Stand 01 08 17 Nach Schulformen

Verzeichnis aller Schulen im Landkreis Osnabrück (Stand: 01.08.2017) Angaben zum Schulträger Name der Schule Straße PLZ Ort Telefon Telefax E-Mail Adresse Internetadresse Schulleiter/in Name des Schulträgers Grundschulen Grundschule Wehrendorf Wischland 12 49152 Bad Essen 05472 2226 05472 959956 [email protected] www.gs-wehrendorf.de Frau Aubke Gemeinde Bad Essen Grundschule Bad Essen Niedersachsenstraße 22 49152 Bad Essen 05472 2263 05472 9499979 [email protected] www.grundschule-bad-essen.de Frau Spang Gemeinde Bad Essen Grundschule Lintorf Bühenkamp 10 49152 Bad Essen 05472 8158970 05472 8158999 [email protected] www.grundschule-lintorf.de Frau Brokamp Gemeinde Bad Essen Grundschule am Salzbach Mühlenstraße 2 49196 Bad Laer 05424 2918-121 05424 2918-19 [email protected] www.grundschule-am-salzbach.de Frau Jung Gemeinde Bad Laer Grundschule Bad Rothenfelde Frankfurter Str. 48 49214 Bad Rothenfelde 05424-4144 05424-2217879 [email protected] www.grundschule-bad-rothenfelde.de/ Frau Bojko Gemeinde Bad Rothenfelde Grundschule Belm Heideweg 30 49191 Belm 05406-4001 05406-899744 [email protected] www.gsb-heideweg.de Herr Röhnisch Gemeinde Belm Grundschule Icker Lechtinger Str. 88 49191 Belm 05406/ 4413 05406/ 806761 [email protected] www.gs-icker.de Frau Walkenhorst (komm.Leitg.) Gemeinde Belm Grundschule Powe Ringstr. 116 49191 Belm 05406/ 83150 05406/ 831530 [email protected] www.osnanet.de/grundschule-powe Herr Brill Gemeinde Belm Grundschule -

For People and Forests

North Rhine-Westphalia 37 % Structure and tasks of the State 11 % Enterprise for Forestry and Timber 16 % 20 % North Rhine-Westphalia 16 % Münsterland Ostwestfalen- The State Enterprise for Forestry and Timber North Rhine- Lippe Westphalia consists of 14 Regional Forestry Offices, the Eifel National Park Forestry Office and the Training and Test Forestry Office in Arnsberg. The forest wardens in a Niederrhein Hoch- sauerland total of 300 forest districts ensure that there is a state- Märkisches Sauerland wide presence. The State Enterprise for Forestry and Timber North Rhine- Westphalia’s main tasks are to sustainably maintain and develop the roles that forests play, to manage the state Imprint Eifel Bergisches Forestry and Timber Land Siegen- Tree species forest and to provide forestry services – e.g. assisting Wittgenstein North Rhine-Westphalia Spruce forest owners in the management of their forests. Published by Pine State Enterprise for Forestry and Timber North Rhine-Westphalia For people and forests Percentage of forest (%) Oak Other tasks include forest supervision (right of access, Public Relations Section 10-20 40-50 Beech Kurt-Schumacher-Str. 50b forest transformation, fire protection, etc.), the implemen- 20-30 50-70 other 59759 Arnsberg Hardwood tation of forestry and forest-based programmes (e.g. with 30-40 E-Mail: [email protected] a view to promoting the energetic and non-energetic use Telephone: +49 251 91797-0 of wood) and the education of the public about the mani- www.wald-und-holz.nrw.de Forest and tree species distribution fold and – above all – elementary significance of the forest www.facebook.com/menschwald in North Rhine-Westphalia to the people. -

Schadstoffmobiltermine 2021 - Nach Orten Sortiert

Schadstoffmobiltermine 2021 - nach Orten sortiert Stand: 30.10.2020 Änderungen vorbehalten! A bis G Ort Ortsteil Sammelstelle Datum Tag Uhrzeit Alfhausen Bahnhofstraße 4, Bauhof 23.07.2021 Fr. 16.00-18.00 Ankum Aslager Straße, Neuer Marktplatz 08.05.2021 Sa. 10.00-12.00 Bad Essen Lintorf Lintorfer Str. Ecke "Am Hallenbad", Parkplatz des VfL-Sportplatzes 26.02.2021 Fr. 15.00-18.00 Bad Essen Niedersachsenstraße 24, Schulhof Grundschule 03.04.2021 Sa. 09.00-12.00 Bad Iburg Charlottenburger Ring 41, "Parkplatz Charlottenburger Ring" 13.03.2021 Sa. 09.00-12.00 Bad Iburg Charlottenburger Ring 41, "Parkplatz Charlottenburger Ring" 15.10.2021 Fr. 15.00-18.00 Bad Laer Weststraße, Parkplatz Sportplatz, (neuer Parkplatz gegenüber Schule/Freibad) 30.04.2021 Fr. 15.00-18.00 Bad Laer Weststraße, Parkplatz Sportplatz, (neuer Parkplatz gegenüber Schule/Freibad) 02.07.2021 Fr. 15.00-18.00 Bad Rothenfelde Ulmenallee, Zentralparkplatz 04.06.2021 Fr. 15.00-18.00 Badbergen Bahnhofstraße, Marktplatz (vor dem Gemeindebüro) 11.09.2021 Sa. 09.00-12.00 Belm Heideweg 25, Parkplatz Sporthalle 10.04.2021 Sa. 10.00-12.00 Belm Vehrte Wittekindsweg (DRK Gebäude) 10.07.2021 Sa. 10.00-12.00 Berge Schienenweg, Parkplatz am Feuerwehrhaus 27.02.2021 Sa. 10.00-12.00 Bersenbrück Im alten Dorfe 4, Bauhof 05.06.2021 Sa. 09.00-12.00 Bippen Am Schützenplatz, Parkplatz hinter der Kreissparkasse 23.04.2021 Fr. 16.00-18.00 Bissendorf Wissingen Bahnhofstraße, Bahnhofsvorplatz 19.03.2021 Fr. 15.00-18.00 Bissendorf Am Schulzentrum, Parkplatz 25.06.2021 Fr. -

Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R

STUDIA FORESTALIA SUECICA NR 39 1966 Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R. An Analysis of Soviet Competitive Potentialities Skogsekonomi i Sovjet~rnionen rned en unalys av landets potentiella konkurrenskraft by KARL VIICTOR ALGTTERE SICOGSH~GSICOLAN ROYAL COLLEGE OF FORESTRY STOCKHOLM Lord Keynes on the role of the economist: "He must study the present in the light of the past for the purpose of the future." Printed in Sweden by ESSELTE AB STOCKHOLM Foreword Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R. is a special study of the forestry sector of the Soviet economy. As such it makes a further contribution to the studies undertaken in recent years to elucidate the means and ends in Soviet planning; also it attempts to assess the competitive potentialities of the U.S.S.R. in international trade. Soviet studies now command a very great interest and are being undertaken at some twenty universities and research institutes mainly in the United States, the United Kingdoin and the German Federal Republic. However, it would seem that the study of the development of the forestry sector has riot received the detailed attention given to other fields. In any case, there have not been any analytical studies published to date elucidating fully the connection between forestry and the forest industries and the integration of both in the economy as a whole. Studies of specific sections have appeared from time to time, but I have no knowledge of any previous study which gives a complete picture of the Soviet forest economy and which could faci- litate the marketing policies of the western world, being undertaken at any university or college. -

Hph-FORUM-2014-Q4.Pdf

DAS INFORMATIONSMAGAZIN DER HEILPÄDAGOGISCHEN HILFE BERSENBRÜCK WINTER 04|2014 · AUSGABEWINTER 80 04|2014 TITELTHEMA AUTONOMIE UND ABHÄNGIGKEIT www.hph-bsb.de rücker Gemeinnützige 22 BEGLEITENDE MaSSNAHME „ARBEITS- GmbH Bersenb nbrück GmbH Werkstätten Reha-Aktiven Berse der ilfe Unternehm Heilpädagogische Hilfe Bersenbrück Heilpädagogischen H nbrück VORWORT Berse SICHERHEIT IN DER WFBM“ Eine Fortbildung HpH Bersenbrück · Pos tfach 1106 · 49587 Bersenbrück Hartmut Baar Bereichsleiter e Rehabilitation 20 Beruflich 3-7 mit vielen Informationen zum Thema rück Robert-Bosch-Straße-32 49593 Bersenb 05439 9449 Telefon 05439 9449-59231 Fax 0170 7934 Mobil de [email protected] www.hph-bsb. @hph-bsb.de www.hph-bsb.de 23 Ha SETALER MUNDRÄUBER-KoNFITÜRE INHALT Heilpädagogische Hilfe Datum Bersenbrück KURZBRIEF auS BERSENBRÜCK Viele neue Produkte Mit der Bitt e um Stellungnahme Erledigung Rücksprache Kenntnisnahme Rückgabe THEMEN WINTER 2014 Konsultationskitas Mit freundlichen Grüßen WOHNEN UND LEBEN zu einer wichtigen Säulegeworden. der 24 VIEL GELERNT BSJler schwärmt von Konsultationskitas sind en fachlichen Weiterbildung und Qualifizierung ualitäts- Sie leisten einen bedeutsamen Beitrag zur praktisch ne und konzeptionellen Unterstützung in der Q entwicklung und -sicherungandere und sind Kindertagesstätten in diesem Sin Erfahrungen Motor und Ideengeber für AKTUELLES in Niedersachsen. - chschülerInnen, Träger Die Aufgabe der Umgebung Pädagogische Fachkräfte, Fa ist nicht, das Kind zu vertreterInnen und weitere Interessierter gelebten erhalten Praxis, -

Um-Maps---G.Pdf

Map Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Catalogued Case Drawer Folder Condition Series or I.D.# Notes Topography, towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gabon - Libreville Service Géographique de L'Armée 1935 1:1,000,000 N 35 10 G1-A F One sheet Cameroon, Gabon, all of Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tomé & Principe Gambia - Jinnak Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 1 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - N'Dungu Kebbe Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 2 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - No Kunda Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 4 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Farafenni Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 5 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kau-Ur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Bulgurk Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kudang Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Fass Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kuntaur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 8 Towns, roads, political -

Forest Ownership in Germany

16.11.2015 AGDW- Federation of German Forest Owner Associations Forest Ownership in Germany total forested area 11,4 mio ha 32 % of total land state forest private 33 % forest 48 % communal forest 19 % 1 16.11.2015 Average Size of Private Ownership 2 Mio private owners 5,48 Mio hectres av. size < 5 ha Who are the private forest owners? < 20 ha 50 % urban owners, small scale farmers, private persons, clerus 20 - 50 ha 11 % mid sacale farmers, private persons, clerus 13% 50 - 100 ha 7 % 6% large farmers, noble families, private persons, clerus 8% 50% 100 - 200 ha 6 % 6% noble families, private persons, entrepreneurs, trusts 7% 200 - 500 ha 8 % 11% noble families, private persons, entrepreneurs, trusts 500 - 1000 ha 6 % noble families, private persons, entrepreneurs, trusts > 1000 ha 13 % noble families, private persons, entrepreneurs, trusts Source: BWI 3 2012 2 16.11.2015 History of Forest Producer Organizations in Germany 1879 – 1917 first grass root forest owner associations „Vereinigung Mitteldeutscher Waldbesitzer“ 1918 establishment of regional forest owner associations reason: fear of expropriation by left wing government 1918 „Bayerischer Waldbesitzerverband WBV 1918“ 1919 foundation of umbrella organization „Reichsverband dt. Waldbesitzerverbände“ 1934 dissolution of all free organizations or inclusion in Nazi organization „Reichsnährstand“ 1945/48 dissolution of all Nazi organizations by Allies WW II 1946/47 reestablishment of regional forest owner associations 1948 foundation of umbrella organization „Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher -

Flyer Kulturelle Sommerfrische 2017

Kulturelle Sommerfrische in der VarusRegion nstaltun n Tagen in sechs Orten Mehr als 90 Vera gen an neu 1.-9. JULI 2017 VERANSTALTUNGSTERMINE Unser Motto: ‚‚Wenn man schnell vorankommen will, muss man alleine gehen, wenn man aber weit kommen will, muss man gemeinsam gehen.“ In der VarusRegion gehen wir gemeinsam erfolgreiche touristische Produkte. Davon pro- I und wir sind zusammen weit gekommen: fitieren auch unsere Bürgerinnen und Bürger. Von ersten gemeinsamen Basisschritten, wie Wir teilen uns die Arbeit und die Kosten – einer Radelkarte, über die bereits zum Klassi- perfekt! Die 1. Kulturelle Sommerfrische war ker avancierte „Kaffeezeit“, die „DiVa Tour“ so erfolgreich, dass wir in 2017 sagen konnten: und den „DiVa Walk“, die Kartoffelplate, den Ja, wir feiern wieder Natur-Kultur-Bewegung TortenSchlachtTag, die Eintopf- und Suppen - in der VarusRegion. Seien Sie dabei: Mehr als tage, die Holunderzeit bis zu unserem jüngsten 90 Veranstaltungen an 9 Tagen in 6 Orten Kind, der „Kirchentour“ – wir haben viele vom 1.–9. Juli 2017! Wir bedanken uns ganz herzlich bei allen Veranstaltern, bei der Volksbank, die die Veranstaltung fördert und wir wünschen uns weiterhin gute, fröhliche, gemeinsame touristische Zusammenarbeit! Gemeinsam sind wir gut: Bad Essen | Belm | Bohmte | Bramsche | Ostercappeln | Wallenhorst IMPRESSUM Herausgeber: VarusRegion im Osnabrücker Land, www.varusregion.de | Erscheinungstermin: Juni 2017 Konzeption, Redaktion: Annette Ludzay & Team Tourist-Info Bad Essen und die Kolleginnen & Kollegen der VarusRegion Gestaltung: bvw werbeagentur & verlag | Fotos: die Kommunen der VarusRegion, Tourismusverband Osnabrücker Land e.V. (TOL) & privat 2 KULTURELLE SOMMERFRISCHE 2017 VarusRegion e Quakenbrück ck Hunt brü Bersen e s a Bohmte d e H n Alfse Kronensee la Kalkriese Art Ostercappeln Bad Essen Bramsche l na ka nd rstenau lla Fü itte ge M hengebir e ie s W a n H Belm uenkirche Wallenhorst Ne Hase Osnabrück rf do lle Me Bissen onn gen eorgsmarienhütte ber T.W.WW G Has a. -

Integriertes Ländliches Entwicklungskonzept (ILEK) Melle

Integriertes ländliches Entwicklungskonzept (ILEK) Melle „Fabelhafter Grönegau“ 1 Impressum Auftraggeber: Stadt Melle Schürenkamp 16 49324 Melle Auftragnehmer: Grontmij GmbH Postfach 34 70 17 28339 Bremen Friedrich-Mißler-Straße 42 28211 Bremen Bearbeitung: Grontmij GmbH Dipl.-Ing. Roland Stahn Dipl.-Ing. Birte Adomat Bildnachweis: Die Quellen sind jeweils am Bild nachgewiesen. Bearbeitungszeitraum: Juli 2014 bis Dezember 2014 Vorgelegt durch: Lenkungsgruppe Grönegau, vertreten durch Bürgermeister Reinhard Scholz Europäischer Landwirtschafts- fonds für die Entwicklung des ländlichen Raums: Hier investiert Europa in die ländlichen Gebiete 2 INHALT Integriertes ländliches Entwicklungskonzept (ILEK) Melle INHALT 1 Zusammenfassung 7 2 Regionsabgrenzung 10 3 Ausgangslage 13 3.1 Raum- und Siedlungsstruktur 13 3.2 Charakterisierung der Orte 16 3.2.1 Buer 16 3.2.2 Bruchmühlen 17 3.2.3 Gesmold 18 3.2.4 Neuenkirchen 19 3.2.5 Wellingholzhausen 20 3.2.6 Riemsloh 21 3.2.7 Oldendorf 22 3.2.8 Dorferneuerungen 24 3.3 Bevölkerungsentwicklung/Demografie 24 3.4 Wirtschaftsstruktur 28 3.5 Landwirtschaft 29 3.6 Soziale Infrastruktur und Daseinsvorsorge 32 3.7 Mobilität 32 3.8 Tourismus 34 3.9 Natur und Umwelt 39 3.10 Klima und Energie 42 3.11 Kunst, Kultur, Bildung 43 3.12 Übergeordnete Planungen 44 3.13 Profil der Region 46 4 SWOT-Analyse 49 4.1 Orts- und Innenentwicklung, Daseinsvorsorge und Infrastruktur, regionale Wirtschaft 49 4.2 Mobilität 52 4.3 Tourismus, Erholung, Sport 53 4.4 Klima, Energie, Umwelt, Naturschutz 55 4.5 Kunst, Kultur und Bildung 56 -

Kommunal Wahl Landkreis Osnabrück Vom 11

Wahlen Die Kommunal Wahl Landkreis Osnabrück vom 11. September 2016 Amtliche Endergebnisse Herausgeber: Landkreis Osnabrück Der Kreiswahlleiter Am Schölerberg 1 49082 Osnabrück 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Erläuterungen...................................................................................................................................... 5 Abgrenzung der Wahlbereiche.............................................................................................................7 Landkreis Osnabrück Ergebnis Tabelle .................................................................................................................................8 Sitzverteilung Kreistag.........................................................................................................................9 Zusammensetzung Kreistag................................................................................................................ 10 Wahlbereich 1 Ergebnis Tabelle..................................................................................................................................12 Stimmzettel..........................................................................................................................................13 Samtgemeinde Artland........................................................................................................................ 14 Badbergen..................................................................................................................................15 Menslage....................................................................................................................................16