Colonisation and Early Peopling of the Colombian Amazon During The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehispanic and Colonial Settlement Patterns of the Sogamoso Valley

PREHISPANIC AND COLONIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERNS OF THE SOGAMOSO VALLEY by Sebastian Fajardo Bernal B.A. (Anthropology), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2006 M.A. (Anthropology), Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Sebastian Fajardo Bernal It was defended on April 12, 2016 and approved by Dr. Marc Bermann, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Olivier de Montmollin, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh Dr. Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History, University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Robert D. Drennan, Distinguished Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Sebastian Fajardo Bernal 2016 iii PREHISPANIC AND COLONIAL SETTLEMENT PATTERNS OF THE SOGAMOSO VALLEY Sebastian Fajardo Bernal, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This research documents the social trajectory developed in the Sogamoso valley with the aim of comparing its nature with other trajectories in the Colombian high plain and exploring whether economic and non-economic attractors produced similarities or dissimilarities in their social outputs. The initial sedentary occupation (400 BC to 800 AD) consisted of few small hamlets as well as a small number of widely dispersed farmsteads. There was no indication that these communities were integrated under any regional-scale sociopolitical authority. The population increased dramatically after 800 AD and it was organized in three supra-local communities. The largest of these regional polities was focused on a central place at Sogamoso that likely included a major temple described in Spanish accounts. -

University of Pittsburgh

University of Pittsburgh CAMPUS: OAKLAND (PITTSBURGH) 2021-22 Factsheet for Incoming Exchange Students CONTACT INFORMATION General Office Information Study Abroad Office, University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh 802 William Pitt Union, 3959 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA ☏ +1 412-648-7413 +1 412-383-1766 [email protected] internationalexchanges.pitt.edu Contact for Incoming & Shawn ALFONSO WELLS (Ms.) Exchange and Panther Program Manager Outgoing Students ☏ +1 412-648-7413 [email protected] Academic Calendar & Fall 2021 Semester Spring 2022 Semester International Student Aug. 15 – 16, 2021 (Tentative) Jan. 11 – 5, 2022 (Tentative) Deadlines Check-in Courses duration Aug. 24 – Dec. 4, 2021 Jan. 11 – Apr. 23, 2022 Final Exams Dec. 7 – 12, 2021 Apr. 26 – May 1, 2022 Nomination Deadlines Application Deadlines Year (Fall & Spring) March 1 March 25 Fall (Semester 1) March 1 March 25 Spring (Semester 2) October 1 October 15 See details: http://internationalexchanges.pitt.edu/deadlines-calendar Application Materials & • Online application. • Passport. Requirements • English Language Requirements. Non-native English speakers must meet one of the minimum requirements: IELTS Band Score 6.5, Duolingo 105 or TOELF iBT 80. Students who score less than 100 on the TOEFL iBT or Band 7.0 on the IELTS must take an additional proficiency test upon arrival. • Transcripts. See details: http://internationalexchanges.pitt.edu/eligibility Tuition Costs & Fees Tuition: No tuition costs. Special Fees: For select courses that require special equipment, such the physical education courses or studio art courses, fees maybe charged. For a list of the courses, please see the “Special Course Related Fees” for the following website here: http://www.registrar.pitt.edu/courseclass.html. -

Heinz Memorial Chapel University of Pittsburgh Public Health Safety Measures

Heinz Memorial Chapel University of Pittsburgh Public Health Safety Measures In order to ensure the safety of visitors to the University’s Heinz Memorial Chapel (the “Chapel”) and to comply with applicable rules, regulations and guidance (including those from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (“CDC”), the Pennsylvania Governor, Pennsylvania Department of Health, and the University of Pittsburgh), the following public health safety measures for weddings at the Chapel are enacted until further notice and may change from time to time: 1. Refund and Rescheduling. Weddings at the Chapel in 2021 may be cancelled by either the University or the wedding couple due to COVID-19. The University shall provide as much advance notice as is reasonable and possible for any cancellation. Wedding couples should understand that given the nature of and risk of a COVID-19 outbreak, a cancellation by the University may occur and may occur without much notice. For any cancellation due to COVID- 19, the wedding couple shall have the option to either: (i) receive a full refund; or (ii) reschedule the wedding to a future available date and time, if any. 2. Safety Requirements. The following measures must be followed at any wedding, memorial or funeral service, baptism, or other event or service at the Chapel until further notice: (i) Rehearsal. Rehearsals will be limited to no more than twenty (20) people (which includes all participants) and will serve as a walkthrough of the ceremony or event with a Chapel coordinator. Masks and six (6)-feet of physical distancing are required. The organist will not be present. -

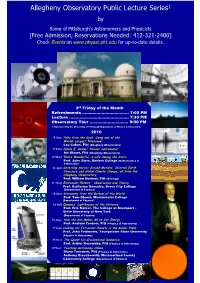

Allegheny Observatory Public Lecture Series1

Allegheny Observatory Public Lecture Series 1 by Some of Pittsburgh’s Astronomers and Physicists [Free Admission, Reservations Needed: 412-321-2400] Check Events on www.phyast.pitt.edu for up-to-date details. 3rd Friday of the Month Refreshments ……….............……........ 7:00 PM Lecture ……..……................................ 7:30 PM Observatory Tour ……….…………..…... 9:00 PM 1. Sponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Department of Physics & Astronomy. 2010 15 Jan : Tales from the Keck: Using one of the Worlds Largest Telescopes Lou Coban, Pitt (Allegheny Observatory) 19 Feb : James E. Keeler: Pioneer Astronomer Art Glaser, Pitt (Allegheny Observatory) 19 Mar : That’s Wonderful, A Life Among the Stars Prof. John Stein, Geneva College (Mathematics & Astronomy) 16 Apr : Detecting nm/sec Ground Motions, Internal Earth Structure and Global Climate Change, all from the Allegheny Observatory Prof. William Harbert, Pitt (Geology) 21 May : Extrasolar Planets – Observation and Theory Prof. Guillermo Gonzalez, Grove City College (Department of Physics) 18 Jun : Astronomy from the Bottom of the World Prof. Tom Oberst, Westminster College (Department of Physics) 16 Jul : Quasars: Lighthouses of the Universe Prof. Eric Monier, The College at Brockport – State University of New York (Department of Physics) 20 Aug : How the Sun Makes All of Our Energy Prof. Andrew Zentner, Pitt (Physics & Astronomy) 17 Sep : Looking for Extrasolar Planets in the Kepler Field Prof. John Feldmeier, Youngstown State University (Physics & Astronomy) 15 Oct : The Quest for Gravitational Radiation Prof. Arthur Kosowsky, Pitt (Physics & Astronomy) 19 Nov : Teaching Astronomy Online Diane Turnshek, Pitt (Physics & Astronomy) Anthony Orzechowski, Westmorland County Community College (Department of Physics). -

Cardinal Glass-NIE World of Wonder 11-19-20

Opening The Windows Of Curiosity Sponsored by Sometimes called the May Flower or the Christmas Orchid, Spec Ad-NIE World Of Wonder 2019 Supporting Ed Top Colombia’s national flower Exploring the realms of history, science, nature and technology is rare and grows high in the cloud forests. The national flag has three horizontal bands of yellow, blue and red. EveryCOLOMBIA color has a different meaning: This South American country is famous for its proud Red symbolizes the blood spilled in people, coffee, emeralds, flowers and, unfortunately, the war for independence. Yellow represents the land’s gold its illegal drug traffic. Colombia is also notable as a and abundant natural riches. Blue signifies the land’s highly diverse country — it is estimated that 1 in every 10 seas, its liberty and sovereignty. Cattleya species of flora and fauna on earth can be found here. trianae orchid In a word Riohacha Just the facts The official name of Colombia Area 440,831 sq. mi. Santa Marta is the Republic of (1,141,748 sq. km) Colombia. It was named for Caribbean Barranquilla Population 50,372,424 the explorer Christopher Co- Sea Valledupar lumbus. The country’s name is Capital city Bogotá Panama pronounced koh-LOHM-bee-ah. Highest elevation City Early Spanish colonists called Montería Pico Cristóbal Colón PANAMA Colombia is the the land New Granada. VENEZUELA 18,947 ft. (5,775 m) Cauca Cúcuta only country in Atrato River South America that Lowest elevation Sea level Looking back River Arauca has coastlines on Agriculture Coffee, cut Medellín both the Pacific Before the Spanish arrived in Puerto Carreño flowers, bananas, rice, tobacco, Pacific Quibdó Ocean and the 1499, the region was inhabited Tunja Caribbean Sea. -

Boletín De Arqueología. Enero De 1990. Año 5. Número 1

EXCAVACIONES ARQUEOLOGICAS EN EL MUNICIPIO DE NEMOCON ""Ana María Groot de Mahecha La investigación arqueológica que había proyectado realizar en la salina de Nemocónsegúnla propuestaquepresentéa la Fundación,debiósermodificada en los comienzos del proceso de trabajo, por motivos que en este informe se presentan. El hallazgo de una estación a cielo abierto relacionado con la presencia de cazadores y recolectores, llamó mi atención, por las posibilidades que ofrecía para complementar la historia del poblamiento prehispánico de la región de Nemocón. Una vez evaluado el potencial de este sitio arqueológico, y frente a un inminente riesgo de que fuera alterado, tomé la decisión de realizarallí una excavación sistemática en área. El trabajo de campo se realizó en dos temporadas; una de dos semanas en la salina y alrededores de Nernocón, y otra, de tres meses en el sitio Checua 1, con la participación de estudiantes de Antropología de la Universidad Nacional. El avance de investigación que aquí se presenta corresponde a esta fase de trabajo, cuya descripción general a continuación se desarrolla. Replanteamiento del Problema de Investigación En el proyecto titulado "Una Actividad Económica Precolombina: realidades y transformaciones de la explotación de sal" me había propuesto como objetivo general el buscar, a través de técnicas arqueológicas, un conocimiento amplio sobre las ocupaciones humanas que poblaron desde tiempos muy antiguos el lugardela salinadeNemocón y susalrededores, tendientea reconoceral patrón de asentamiento, la adaptación -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Inclusive Protected Area Management in the Amazon: the Importance of Social Networks Over Ecological Knowledge

Sustainability 2012, 4, 3260-3278; doi:10.3390/su4123260 OPEN ACCESS sustainability ISSN 2071-1050 www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability Article Inclusive Protected Area Management in the Amazon: The Importance of Social Networks over Ecological Knowledge Paula Ungar 1,* and Roger Strand 2 1 Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Research on Biological Resources, Avenida Paseo de Bolívar (Circunvalar) 16–20, Bogotá, Colombia 2 Centre for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities, University of Bergen, P.O. Box 7805, N-5020 Bergen, Norway; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +57-1-3202-767; Fax: +57-1-320-2767. Received: 3 September 2012; in revised form: 5 November 2012 / Accepted: 16 November 2012 / Published: 30 November 2012 Abstract: In the Amacayacu National Park in Colombia, which partially overlaps with Indigenous territories, several elements of an inclusive protected area management model have been implemented since the 1990s. In particular, a dialogue between scientific researchers, indigenous people and park staff has been promoted for the co-production of biological and cultural knowledge for decision-making. This paper, based on a four-year ethnographic study of the park, shows how knowledge products about different components of the socio-ecosystem neither were efficiently obtained nor were of much importance in park management activities. Rather, the knowledge pertinent to park staff in planning and management is the know-how required for the maintenance and mobilization of multi-scale social-ecological networks. We argue that the dominant models for protected area management—both top-down and inclusive models—underestimate the sociopolitical realm in which research is expected to take place, over-emphasize ecological knowledge as necessary for management and hold a too strong belief in decision-making as a rational, organized response to diagnosis of the PA, rather than acknowledging that thick complexity needs a different form of action. -

Travel Birdwatching Birds of Colombia

Travel Birdwatching Birds of Colombia Bogotá – Tolima - Eje Cafetero - Amazonas Program # 04 description: Day 01. Bogotá: Arrival at Bogotá, the capital of Colombia. Welcoming reception at the airport and transportation to the hotel. Accommodation. Day 02. Bogotá: Breakfast in the hotel and transportation to Swamp Martos of Guatavita, 2600 – 3150 m above sea level. This area offers more than 2000 ha of forest mists, wetlands and upland moors, where we can see more than 100 species that live there between the endemic, endangered and migratory: Brown-breasted Parakeet; Bogota Rail; Black-billed Mountain Toucan; Torrent Duck; White capped Tanager; Rufous-brwed Conebill. Day 03. Bogotá: Breakfast in the hotel of Bogotá and fieldtrip for two days to the Natural Park Chicaque. This park is located 40 minutes away from the capital of Colombia between 2100 and 270 m. above sea level. There are 300 ha of oak forests (Quercus humboldtii). Here we will able to see more than 210 species of birds of different colors and incomparable beauty, among these are: Rufous-browed Conebill; Flame-faced Tanager; Saffron-crowned Tanager; Esmerald Toucan; Capped Conebiill; Black Inca Endemic); Turquoise Dacnis (endemic). Day 04. Chicaque - Tolima: Breakfast in the hotel and transportation to the Canyon of Combeima in the department of Tolima. During the road trip we will visit the Hacienda La Coloma, where the coffee that is exported is produced. There will we learn all the different processes of how the seeds are selected and how to differentiate quality coffee. Lunch and accommodation in the city of Ibagué, the capital of Tolima. -

South America Highlights

Responsible Travel Travel offers some of the most liberating and rewarding experiences in life, but it can also be a force for positive change in the world, if you travel responsibly. In contrast, traveling without a thought to where you put your time or money can often do more harm than good. Throughout this book we recommend ecotourism operations and community-sponsored tours whenever available. Community-managed tourism is especially important when vis- iting indigenous communities, which are often exploited by businesses that channel little money back into the community. Some backpackers are infamous for excessive bartering and taking only the cheapest tours. Keep in mind that low prices may mean a less safe, less environmentally sensitive tour (espe- cially true in the Amazon Basin and the Salar de Uyuni, among other places); in the market- place unrealistically low prices can negatively impact the livelihood of struggling vendors. See also p24 for general info on social etiquette while traveling, Responsible Travel sec- tions in individual chapter directories for country-specific information, and the GreenDex ( p1062 ) for a list of sustainable-tourism options across the region. TIPS TO KEEP IN MIND Bring a water filter or water purifier Respect local traditions Dress appropri Don’t contribute to the enormous waste ately when visiting churches, shrines and left by discarded plastic water bottles. more conservative communities. Don’t litter Sure, many locals do it, but Buyer beware Don’t buy souvenirs or many also frown upon it. products made from coral or any other animal material. Hire responsible guides Make sure they Spend at the source Buy crafts directly have a good reputation and respect the from artisans themselves. -

Ralph Bauer Associate Dean for Academic

CURRICULUM VITAE Ralph Bauer Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, College of Arts and Humanities Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature 1102 Francis Scott Key Hall University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-7311 Phone: 301 405 5646 E-Mail: [email protected] https://www.english.umd.edu/profiles/rbauer ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: August 2004 to present: Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature, University of Maryland. May – July 2011: Visiting Professor, American Studies, University of Tuebingen. August 2006 to August 2007: Associate Visiting Professor, Department of English and Department of Spanish and Portuguese, New York University June 2006 to July 2006: Visiting Associate Professor, Department of American Studies, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany. August 1998- August 2004: Assistant Professor of English, University of Maryland. August 1997- August 1998: Assistant Professor of English, Yale University. 1992-1996 Graduate Instructor, Michigan State University, Department of English, Department of American Thought and Language, Department of Integrative Studies in Arts and Humanities. ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS: August 2017 to present: Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, College of Arts and Humanities. 20013-2016: Director of Graduate Studies, Department of English, University of Maryland, College Park 2003 -2006: Director of English Honors, University of Maryland, College Park. EDUCATION: Ph. D., American Studies, 1997, Michigan State University. M. A., American Studies, 1993, Michigan State University. Undergraduate Degrees (Zwischenpruefung), 1991, in English, German, and Spanish, University of Erlangen/Nuremberg, Germany. SCHOLARSHIP: MONOGRAPHS: The Alchemy of Conquest: Science, Religion, and the Secrets of the New World (forthcoming from the University of Virginia Press, fall 2019). The Cultural Geography of Colonial American Literatures: Empire, Travel, Modernity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003; paperback 2008). -

Quaternary International Colonisation and Early Peopling of The

Quaternary International xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Colonisation and early peopling of the Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene and the Early Holocene: New evidence from La Serranía La Lindosa ∗ Gaspar Morcote-Ríosa, Francisco Javier Aceitunob, , José Iriartec, Mark Robinsonc, Jeison L. Chaparro-Cárdenasa a Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia b Departamento de Antropología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia c Department of Archaeology, Exeter, University of Exeter, United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Recent research carried out in the Serranía La Lindosa (Department of Guaviare) provides archaeological evi- Colombian amazon dence of the colonisation of the northwest Colombian Amazon during the Late Pleistocene. Preliminary ex- Serranía La Lindosa cavations were conducted at Cerro Azul, Limoncillos and Cerro Montoya archaeological sites in Guaviare Early peopling Department, Colombia. Contemporary dates at the three separate rock shelters establish initial colonisation of Foragers the region between ~12,600 and ~11,800 cal BP. The contexts also yielded thousands of remains of fauna, flora, Human adaptability lithic artefacts and mineral pigments, associated with extensive and spectacular rock pictographs that adorn the Rock art rock shelter walls. This article presents the first data from the region, dating the timing of colonisation, de- scribing subsistence strategies, and examines human adaptation to these transitioning landscapes. The results increase our understanding of the global expansion of human populations, enabling assessment of key inter- actions between people and the environment that appear to have lasting repercussions for one of the most important and biologically diverse ecosystems in the world.