International Journal of Hinduism & Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled By Mukund Ainapure i Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled by Mukund Ainapure • Original Sanskrit Verses from the Rig Veda cited in The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo Volume 16, Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Part II – Mandala 5 • Padpātha Sanskrit Verses after resolving euphonic combinations (sandhi) and the compound words (samās) into separate words • Sri Aurobindo’s English Translation matched word-by-word with Padpātha, with Explanatory Notes and Synopsis ii Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Volume III By Mukund Ainapure © Author All original copyrights acknowledged April 2020 Price: Complimentary for personal use / study Not for commercial distribution iii ॥ी अरिव)दचरणारिव)दौ॥ At the Lotus Feet of Sri Aurobindo iv Prologue Sri Aurobindo Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta on 15 August 1872. At the age of seven he was taken to England for education. There he studied at St. Paul's School, London, and at King's College, Cambridge. Returning to India in 1893, he worked for the next thirteen years in the Princely State of Baroda in the service of the Maharaja and as a professor in Baroda College. In 1906, soon after the Partition of Bengal, Sri Aurobindo quit his post in Baroda and went to Calcutta, where he soon became one of the leaders of the Nationalist movement. -

The Vaiesikastra S9-1 Referred to in the Yuktidipik Shujun Motegi

Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies Vol. 36, No. 2, March 1988 The Vaiesikastras9-1 referred to in the Yuktidipik Shujun Motegi The Vaisesika-sutra (=vs)1) is a text of ambiguity, which contains not a few obscure sutras. In the present paper, I would take up VS 9-1 as one of such sutras and discuss its meaning with the help of the reference in the Yuktidipika (=YD)2>, an anonymous commentary of the Samkhyakarika. VS 9-1 runs: kriya-guna-vyapadesabhavad asat. (An effect does not exist in a cause because there is no such inferential mark as kriya-guna-vyapadesa to show its existence in a cause. ) This sutra explains one of the four patterns of non-existence, and as the result supports the asatkaryavad a, which is a typical Vaisesika theory of causation. According to the Vaisesika school, the empirical world is constituted by connec- tion and dissociation of atoms (paramanu). Material beings (karyas) are always newly constituted by connection and dissociation of atoms, so that they can not be supposed to exist (asat) in preceedingly existent beings. To prove this point of view, the sutra presents the inferential mark (linga), that is, kriya-guna-vya- pad esa. Before going into examination of the VS referred to in the YD, we have to cast a glace on the commentaries of the VS to see the Vaisesika tradition of in- terpretation. The commentaries of the VS don't agree with each other in the reading of the compound word kriya-guna-vyapadesa. Candrananda, for exam- ple, interprets VS 9-1 as follows : na tavat karyam prag utpatteh pratyaksena grhyate / napy anumdnena, sati liege tasya bhavat, liiigabhavas ca tadiyayoh kriyagunayor anupalabdheh, na canyad vyapadesa- sabdasucitam lingam asti / tasmat prag utpatter asat / (Candrananda's Vrtti, p. -

Annual Report 2003-2004

ANNUAL REPORT 2003-2004 ■inaiiiNUEPA DC D12685 UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi-110 002 (India) UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION LIST OF THE COMMISSION MEMBERS DURING 2003-2004 Chairman Dr. Arun Nigavekar ■;ir -Chariman Prof. V.N. Rajasekharan Pillai /».. bers 1. Shri S.K. Tripathi 2. Shri Dinesh Chander Gupta 3. Dr. S.K. Joshi 4. Prof. Sureshwar Sharma ++ 5. Prof. B.H. Briz Kishore ++ 6. Prof. Vasant Gadre 7. Prof. Ashok Kumar Gupta 8. Dr. G. Mohan Gopai * 9. Dr. G. Karunakaran Pillai 10. Prof. Arana Goel 11. Dr. P.N. Tandon$ Secretary Prof. Ved Prakash # w.e.f. 30.04.2003 ++ Second Term w.e.f. 16.06.2003 * upto 11.06.2003 $ w.e.f. 12.06.2003 CONTENTS Highlights of the University Grants Commission 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Role and Organization of UGC 13 1.2 About Tenth Plan 14 1.3 Special Cells Functioning in the UGC 15 a) Malpractices Cell 15 b) Legal Cell 16 c) Vigilance Cell 17 d) Pay Scale Cell 17 e) Sexual Harassment Complaint Committee of UGC 17 f) Internal Audit Cell 17 g) Desk: Parliament Matters 18 1.4 Publications 19 1.5 The Budget and Finances of UGC 19 1.6 Computerisation of UGC 20 1.7 Highlights of the Year 21 2. Higher Education System: Statistical Growth of Institutions, Enrolment, Faculty and Research 2.1 Institutions 36 2.2 Students Enrolment 38 2.3 Faculty Strength 38 2.4 Research Degrees 39 2.5 Growth in Enrolment of Women in Higher Education 39 2.6 Distribution of Women Enrolment by State, Stage and Faculty 39 2.7 Women Colleges 41 3. -

Ashtavakra Gita

Chapter 5 to 15 Volume – 02 Index Chapter Title Verses Page No Introduction 1 to 9 1 Self - Witness in all 20 9 to 62 2 The Marvellous Self 25 63 to 142 3 Self in All - All in Self 14 143 to 174 4 Glory of Realisation 6 175 to 194 5 Four Methods - Dissolution of Ego 4 195 to 208 6 The Self Supreme 4 209 to 224 7 That Tranquil Self 5 225 to 236 8 Bondage and Freedom 4 237 to 242 9 Indifference 8 243 to 259 10 Dispassion 8 260 to 275 11 Self As Pure Intelligence 8 276 to 293 12 How to Abide in the Self 8 294 to 305 13 The Bliss Absolute 7 306 to 325 14 Tranquillity 4 326 to 339 i Chapter Title Verses Page No 15 Brahman - The Absolute Reality 20 340 to 385 16 Self-abidance - Instructions 11 386 to 405 17 Aloneness of the Self 20 406 to 468 18 The Goal 100 469 to 570 19 The Grandeur of the self 8 NIL 20 The Absolute state 14 NIL Total 298 ii Index S. No. Verses Page No Chapter 5 - Four Methods - Dissolution of Ego 67 Verse 1 197 68 Verse 2 201 69 Verse 3 203 70 Verse 4 207 Chapter 6 - The Self Supreme 71 Verse 1 211 72 Verse 2 218 73 Verse 3 219 74 Verse 4 220 Chapter 7 - That Tranquil Self 75 Verse 1 227 76 Verse 2 228 77 Verse 3 229 78 Verse 4 230 79 Verse 5 232 iii S. -

A Report on Pilot Social Audit of Mid Day Meal Programme May, 2015

A Report on Pilot Social Audit of Mid Day Meal Programme May, 2015 Submitted to: Secretary, School and Mass Education Department, Odisha Prepared by: Lokadrusti, At- Gadramunda, Po- Chindaguda, Via- Khariar, Dist.- Nuapada (Odisha) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Lokadrusti has been assigned the project of “Pilot Social Audit of Mid Day Meal Programme in Nuapada district” by State Project Management Unit (MDM), School and Mass Education Department, Government of Odisha. I am thankful to Secretary, School and Mass Education Department, Government of Odisha, for providing an opportunity to undertake this activity of social audit of MDM. I acknowledge the support extended by the Director and state project management unit of MDM, Odisha from time to time. I am thankful to the District Education Officer, District Project Coordinator of Sarva Sikhya Abhiyan, Nuapada and Block Education Officer of Boden and Khariar block for their support and cooperation. My heartfelt thanks to all the social audit resource persons, village volunteers, School Management Committee members, parents, students, cooks, Panchayatiraj representatives and Women Self Help Group members those helped in conducting the field visit, data collection, focused group discussions and village level meetings. I express all the headmasters and teachers in the visited schools for providing us with relevant information. I am extremely thankful to the Lokadrusti team members to carry this project of social relevance and document the facts for public vigilance and to highlight the grass root level problems of MDM scheme to plan further necessary interventions. Abanimohan Panigrahi Member Secretary, Lokadrusti [i] Preface Primary school children (6-14 years) form about 20 per cent of the total population in India. -

Audit Bureau of Circulations

Audit Bureau Of Circulations Founder Member : International Federation of Audit Bureaux of Circulations Wakefield House, Sprott Road, Ballard Estate, Mumbai – 400 001 Tel: +91 22 2261 18 12 / 2261 90 72 . Fax: +91 22 2261 88 21 E-mail :[email protected] Web Site : http://www.auditbureau.org 21st October, 2016 To, All Members Notification No. 846 PART I: AMENDMENT TO BUREAU’S CODE FOR PUBLICITY – DISCLAIMER FOR VARIANT COPIES To be added under para 2(a)(ii) under the heading “Definitions/scope” 2. a) DISCLAIMER A disclaimer in the same font and size as the main claim is required to be mentioned whenever variant copies are included in the total copies for any claim, publicity, ranking, advertisement, hoardings etc. or any other form of publicity. (main claim would be considered as one which projects – leading, highest, number one, rankings etc. and / or a claim with the largest font size) For example: If total copies of average 1,00,000 includes average 10,000 variant copies, (details of which are available on the ABC certificate of circulation) then it is necessary to mention that “the total circulation of average 1,00,000 copies includes average 10,000 variant copies” in the same font and size as of the main claim. Publisher members however can claim / publicise based on their total certified circulation figures including variant copies. This disclaimer would apply in all cases including comparison made for State, District or Town based on Area Distribution Statement certified by ABC and available to all members. This provision for a disclaimer clause was earlier intimated to all publisher members as well as discussed in detail with all publisher members in August 2016. -

Paninian Studies

The University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA Ann Arbor, Michigan STUDIES Professor S. D. Joshi Felicitation Volume edited by Madhav M. Deshpande Saroja Bhate CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Number 37 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress catalog card number: 90-86276 ISBN: 0-89148-064-1 (cloth) ISBN: 0-89148-065-X (paper) Copyright © 1991 Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-064-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-89148-065-5 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12773-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90169-2 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ CONTENTS Preface vii Madhav M. Deshpande Interpreting Vakyapadiya 2.486 Historically (Part 3) 1 Ashok Aklujkar Vimsati Padani . Trimsat . Catvarimsat 49 Pandit V. B. Bhagwat Vyanjana as Reflected in the Formal Structure 55 of Language Saroja Bhate On Pasya Mrgo Dhavati 65 Gopikamohan Bhattacharya Panini and the Veda Reconsidered 75 Johannes Bronkhorst On Panini, Sakalya, Vedic Dialects and Vedic 123 Exegetical Traditions George Cardona The Syntactic Role of Adhi- in the Paninian 135 Karaka-System Achyutananda Dash Panini 7.2.15 (Yasya Vibhasa): A Reconsideration 161 Madhav M. Deshpande On Identifying the Conceptual Restructuring of 177 Passive as Ergative in Indo-Aryan Peter Edwin Hook A Note on Panini 3.1.26, Varttika 8 201 Daniel H. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

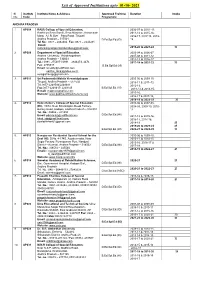

List of Approved Institutions Upto 11-08

List of Approved Institutions upto 01-10- 2021 Sl. Institute Institute Name & Address Approved Training Duration Intake No. Code Programme ANDHRA PRADESH 1. AP004 RASS College of Special Education, 2006-07 to 2010 -11, Rashtriya Seva Samiti, Seva Nilayram, Annamaiah 2011-12 to 2015-16, Marg, A.I.R. Bye – Pass Road, Tirupati, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018- Andhra Pradesh – 517501 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(ID) 19, Tel No.: 0877 – 2242404 Fax: 0877 – 2244281 Email: [email protected]; 2019-20 to 2023-24 30 2. AP008 Department of Special Education, 2003-04 to 2006-07 Andhra University, Vishakhapatnam 2007-08 to 2011-12 Andhra Pradesh – 530003 2012-13 to 2016-17 Tel.: 0891- 2754871 0891 – 2844473, 4474 2017-18 to 2021-22 30 Fax: 2755547 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(VI) Email: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] 3. AP011 Sri Padmavathi Mahila Visvavidyalayam , 2005-06 to 2009-10 Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh – 517 502 2010-11 & 2011–12 Tel:0877-2249594/2248481 2012-13, Fax:0877-2248417/ 2249145 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2013-14 & 2014-15, E-mail: [email protected] 2015-16, Website: www.padmavathiwomenuniv.org 2016-17 & 2017-18, 2018-19 to 2022-23 30 4. AP012 Helen Keller’s College of Special Education 2005-06 to 2007-08, (HI), 10/72, Near Shivalingam Beedi Factory, 2008-09, 2009-10, 2010- Bellary Road, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh – 516 001 11 Tel. No.: 08562 – 241593 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) Email: [email protected] 2011-12 to 2015-16, [email protected]; 2016-17, 2017-18, [email protected] 2018-19 25 2019-20 to 2023-24 25 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2020-21 to 2024-25 30 5. -

Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature

YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Studia Orientalia 116 YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Helsinki 2015 Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Klaus Karttunen Studia Orientalia, vol. 116 Copyright © 2015 by the Finnish Oriental Society Editor Lotta Aunio Co-Editor Sari Nieminen Advisory Editorial Board Axel Fleisch (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Middle Eastern and Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Assyriology) Jaana Toivari-Viitala (Egyptology) Typesetting Lotta Aunio ISSN 0039-3282 ISBN 978-951-9380-88-9 Juvenes Print – Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy Tampere 2015 CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................................................................................... XV PART I: REFERENCES IN TEXTS A. EPIC AND CLASSICAL SANSKRIT ..................................................................... 3 1. Epics ....................................................................................................................3 Mahābhārata .........................................................................................................3 Rāmāyaṇa ............................................................................................................25 -

Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

S International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India Volume: 7 Abstract Disability has been the inescapable part of human society from ancient times. With the thrust of Issue: 1 disability right movements and development in eld of disability studies, the mythical past of dis- ability is worthy to study. Classic Indian Scriptures mention differently able character in prominent positions. There is a faulty opinion about Indian mythology is that they associate disability chie y Month: July with evil characters. Hunch backed Manthara from Ramayana and limping legged Shakuni from Mahabharata are negatively stereotyped characters. This paper tries to analyze that these charac- ters were guided by their motives of revenge, loyalty and acted more as dramatic devices to bring Year: 2019 crucial changes in plot. The deities of lord Jagannath in Puri is worshipped , without limbs, neck and eye lids which ISSN: 2321-788X strengthens the notion that disability is an occasional but all binding phenomena in human civiliza- tion. The social model of disability brings forward the idea that the only disability is a bad attitude for the disabled as well as the society. In spite of his abilities Dhritrashtra did face discrimination Received: 31.05.2019 because of his blindness. The presence of characters like sage Ashtavakra and Vamanavtar of Lord Vishnu indicate that by efforts, bodily limitations can be transcended. Accepted: 25.06.2019 Keywords: Karma, Medical model, Social model, Ability, Gender, Charity, Rights. -

Why Should I Take Admission in NIOS Vocational Education Courses?

PROSPECTUS 2013 With Application Form for Admission Vocational Education Courses National Institute of Open Schooling (An autonomous organisation under MHRD, Govt. of India) A-24-25, Institutional Area, Sector-62, NOIDA (U.P.) - 201309 Website: www.nios.ac.in “The Largest Open Schooling System in the World” i Why should I take admission in Facts and Figures NIOS Vocational Education Courses? about NIOS l The largest Open Schooling system in the world: more than 1. Freedom to Learn 2.45 million learners have taken admission since 1990. With the motto to ‘reach out and reach all’, the NIOS follows the principle of freedom to learn. What to learn, when to learn, l More than 25,000 learners take how to learn and when to appear for the examination is decided admission every year in Vocational Education Courses by you. There is no restriction of time, place and pace of and more than 3,50,000 are learning. enrolled in all the courses and programmes. 2. Flexibility l 1,44,799 learners have been The NIOS provides flexibilities such as: certified in different Vocational Education Courses since May l Round the year Admission: You can take admission online or through Accredited 1993. Vocational Institute round the year. Admission in Vocational Courses can also be done through On-line mode. l NIOS reaches out to its clients through a network of more l Choice of courses: Choose courses of your choice from the given list keeping than 1725 Vocational Education the eligibility criteria in mind. centres spread all over the l Examination when you want: Public Examinations are held twice in a year.