Sectarian Violence in Pakistan's Kurram Agency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(FATA) of Pakistan: Conflict Management at State Level

TIGAH,,, A JOURNAL OF PEACE AND DEVELOPMENT Volume: II, December 2012, FATA Research Centre, Islamabad Peacebuilding in FATA: Conflict Management at State Level Peacebuilding in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan: Conflict Management at State Level Sharafat Ali Chaudhry ∗ & Mehran Ali Khan Wazir ! Abstract Studies focusing on violence in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) conclude that the Russian aggression in 1979 towards Afghanistan, anarchy in post-soviet era, and US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 are the key reasons of spreading of violence in FATA. However, there is a controversy in views about the nature of violence in the bordering areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan. This paper empirically analyzes three dimensions of wide spread violence in the area. First, it maps the current research and views on the nature of violence in FATA. Second, it examines meta-theories of peacemaking and their relevance to the cultural, social and historical context of the tribal belt. Finally, this paper proposes the policy options for conflict management at the state level in Pakistan. Introduction The conflict in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) has been explored to greater extent and the majority of studies conclude that the current violence in FATA has its roots within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) invasion of Afghanistan which ended up in the Afghan civil war. Soviet invasion pulled the United States of America (USA) into this region. The US won the proxy war in Afghanistan against USSR ∗ Sharafat Ali Chaudhry, a development professional-turned-Lawyer, has been visiting faculty member at Department of P&IR at IIU, Islamabad. -

The Haqqani Network in Kurram the Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency

May 2011 The haQQani NetworK in KURR AM THE REGIONAL IMPLICATIONS OF A GROWING INSURGENCY Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ©2011 by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project Cover image courtesy of Dr. Mohammad Taqi. the haqqani network in kurram The Regional Implications of a Growing Insurgency Jeffrey Dressler & Reza Jan A Report by the Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project ACKNOWLEDGEMENts This report would not have been possible without the help and hard work of numerous individuals. The authors would like to thank Alex Della Rocchetta and David Witter for their diligent research and critical support in the production of the report, Maggie Rackl for her patience and technical skill with graphics and design, and Marisa Sullivan and Maseh Zarif for their keen insight and editorial assistance. The authors would also like to thank Kim and Fred Kagan for their necessary inspiration and guidance. As always, credit belongs to many, but the contents of this report represent the views of the authors alone. taBLE OF CONTENts Introduction.....................................................................................1 Brief History of Kurram Agency............................................................1 The Mujahideen Years & Operation Enduring Freedom .............................. 2 Surge of Sectarianism in Kurram ...........................................................4 North Waziristan & The Search for New Sanctuary.....................................7 -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

OCHA Pakistan Weekly Return Snapshot 12 May 2016

Pakistan: FATA Return [Subject] Weekly (as of XX Snapshot Mmm YYYY) (from 6 to 12 May 2016) Families Families Families Families Total returned % Returned & returned returned in 2016 returned total* remaining in female-headed displaced this week displacement households* Returned 48% 52% 2,331 33,573 146,346 157,445 17% * since 16 March 2015 Displaced Returns continue at a regular pace with 2,331 families returning during the week of 6 Nangarhar Jammu Aksai Area of Detail and Kashmir to 12 May. As before, the bulk of returns are to North Waziristan and South Waziristan AFGHANISTAN Peshawar Islamabad Agencies. Twenty six families have returned to Orakzai in the past week, concluding Shalobar ! Nowshera Upper New ") ! Kurram ! Durrani Khyber this phase of Orakzai returns. The next two phases of Orakzai returns will address the Indus Jalozai IRAN Paktya Kurram ") Shahkas remaining 21,252 families, although exact dates for these returns have not yet been INDIA FATA Chamjana Arabian Karachi Orakzai announced. The current phase of Kurram returns has also concluded. The next phase Sea Lower ! Jerma Kurram ! Hangu will begin following further denotifications within Kurram. Togh Kohat Khost Shewa Sarai Afghanistan Spinwam FR Bannu Mir ! Bakka Khel North ") ! Khan Bannu Waziristan ") Punjab Garyum Jalir Mirzail Check as of 28 April 2016 Post Total Government transport and return grant RazmakDossali 50km Khandaisar") Ladha Paktika ") FR Tank Khyber ! million or PKR 4,236 million worth of support packages disbursed Tiraza Camp $41 ") Sararogha ") Humanitarian hub 19% 18% Pakhtunkhwa Tank Embarkation point 113,642 grants of PKR10,000 123,998 grants of PKR25,000 South Sarwakai ! Waziristan Return agencies have been disbursed to families have been disbursed to families Khairgai for the transport package for the return package De-notified areas % disbursed to female % disbursed to female headed households headed households The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Origination, Organization, and Prevention: Saudi Arabia, Terrorist Financing and the War on Terror”

Testimony of Steven Emerson with Jonathan Levin Before the United States Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs “Terrorism Financing: Origination, Organization, and Prevention: Saudi Arabia, Terrorist Financing and the War on Terror” July 31, 2003 Steven Emerson Executive Director The Investigative Project 5505 Conn. Ave NW #341 Washington DC 20015 Email: [email protected] phone 202-363-8602 fax 202 966 5191 Introduction Terrorism depends upon the presence of three primary ingredients: Indoctrination, recruitment and financing. Take away any one of those three ingredients and the chances for success are geometrically reduced. In the nearly two years since the horrific attacks of 9/11, the war on terrorism has been assiduously fought by the US military, intelligence and law enforcement. Besides destroying the base that Al Qaeda used in Afghanistan, the United States has conducted a comprehensive campaign in the United States to arrest, prosecute, deport or jail those suspected of being connected to terrorist cells. The successful prosecution of terrorist cells in Detroit and Buffalo and the announcement of indictments against suspected terrorist cells in Portland, Seattle, northern Virginia, Chicago, Tampa, Brooklyn, and elsewhere have demonstrated the resolve of those on the front line in the battle against terrorism. Dozens of groups, financial conduits and financiers have seen their assets frozen or have been classified as terrorist by the US Government. One of the most sensitive areas of investigation remains the role played by financial entities and non-governmental organizations (ngo’s) connected to or operating under the aegis of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Since the July 24 release of the “Report of the Joint Inquiry into the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001,” the question of what role Saudi Arabia has played in supporting terrorism, particularly Al Qaeda and the 9/11 attacks, has come under increasing scrutiny. -

The Races of Afghanistan

4 4 4 4 /fi T H E A C ES O F A F G H A N I STA N , A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF TH E PRINCIPAL NATIONS HA TH A C U RY IN BITING T O NT . ”fi — Q ~ v n o Q ‘ A “ 0 - H B EL L EW M J O . W . S URGEO N A R , L A T E 0N S P E C I A L P O L I T I C A L D U T Y A T KA B UL . L C ALCUTTA C K E S P N K A N D C C . T H A R, I , T R U BN E C O NV . R C O . LONDON : R AND . ; THACKE AND "" M D C C C L " . A ll ri h ts r served " g e . ul a u fi N J 989“ Bt u21 5 PR IN T D B Y T R A C KE R S P IN K E , , PR EF A C E. T H E manuscript o f t he fo llo wing bri e f a c c o unt o f t he ra c es of Af ha s a wa s w e n a t Kab u fo r th e g ni t n ritt l , m os ar a f er the d u e s o f t he d a we e o e r a nd a t t p t, t ti y r v , o d n e rva s o f e sure fr m o ffic a bus ess h t h e d i t l l i o i l in , wit vi ew t o it s t rans mi ss i o n t o Engl a nd fo r p ubli c a ti o n b ut fa n as d e w t o a c o se and b e n o b e d lli g ill it r l , i g lig o n tha t a c c o unt t o l ea ve Ka bul fo r In di a o n s i ck ' e ve m u o se c ou d no t b e c a d o ut . -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

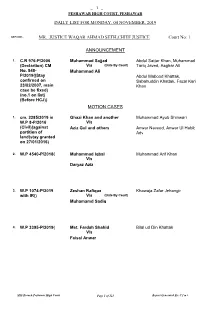

Single Bench List for 04-11-2019

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 NOVEMBER, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 ANNOUNCEMENT 1. C.R 976-P/2006 Muhammad Sajjad Abdul Sattar Khan, Muhammad (Declartion) CM V/s (Date By Court) Tariq Javed, Asghar Ali No. 848- Muhammad Ali P/2019((Stay Abdul Mabood Khattak, confirned on Sabahuddin Khattak, Fazal Karim 23/02/2007, main Khan case be fixed) (no.1 on list) (Before HCJ)) MOTION CASES 1. cm. 2285/2019 in Ghazi Khan and another Muhammad Ayub Shinwari W.P 8-P/2016 V/s (Civil)(against Aziz Gul and others Anwar Naveed, Anwar Ul Habib partition of Adv land(stay granted on 27/01/2016) 2. W.P 4540-P/2018() Muhammad Iqbal Muhammad Arif Khan V/s Daryaz Aziz 3. W.P 1074-P/2019 Zeshan Rafique Khawaja Zafar Jehangir with IR() V/s (Date By Court) Muhamamd Sadiq 4. W.P 3395-P/2019() Mst. Fardah Shahid Bilal ud Din Khattak V/s Faisal Anwar MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 121 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR MONDAY, 04 NOVEMBER, 2019 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE WAQAR AHMAD SETH,CHIEF JUSTICE Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 5. W.P 4300-P/2019() Afzal Imran Ali Mohmand V/s Mst. Rashida i W.P 4716/2019 Mst Rashida Abid Ayub V/s Afzal 6. Cr.M(BCA) 3065- The State Waqas Khan Chamkani P/2019() V/s Noor Dad Khan 7. Cr.M(BCA) 3100- Muhammad Yousaf Syed Abdul Fayaz P/2019() V/s Abdullah Cr Appeal Branch AG Office 8. -

Afghan Opiate Trade 2009.Indb

ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium Copyright © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2009 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), in the framework of the UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme/Afghan Opiate Trade sub-Programme, and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC field offices for East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Southern Africa, South Asia and South Eastern Europe also provided feedback and support. A number of UNODC colleagues gave valuable inputs and comments, including, in particular, Thomas Pietschmann (Statistics and Surveys Section) who reviewed all the opiate statistics and flow estimates presented in this report. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including, in particular, the Anti Narcotics Force of Pakistan, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan and the World Customs Organization. Thanks also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and of the United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Lead researcher, Afghan -

Khushal Khan Khattak and Swat

Sultan-i-Rome KHUSHAL KHAN KHATTAK AND SWAT Khushal Khan Khattak was a prominent and versatile Pukhtun poet and prose writer. He was also a swordsman and being very loyal to the Mughals, he served them with full dedication like his ancestors against his fellow Yusufzai and Mandarn (commonly referred to as Yusufzai) Pukhtuns for a long time before he turned against the Mughals. Due to some disagreements and decreasing favours from the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, Khushal Khan Khattak endeavoured to instigate the Pukhtun tribes against him. In this connection he visited Swat as well. He has praised Swat and its scenic beauty, and has made its comparison with Kabul and Kashmir in this respect but has reviled and condemned the people of Swat for various things and traits. In the course of his tour of Swat, Khushal Khan fell in certain controversies which led to serious disputes and debates with Mian Noor: a reverend religious figure in Swat at that time. This created fresh grudges between him and the people of Swat, and the Swati Yusufzai therefore did not support him in his campaign against Aurangzeb. Besides, the Swati people were in no conflict with Aurangzeb. Therefore it was not to be expected of them to make a common cause with a person who and his ancestors remained loyal to the Mughals and served them to their best against the Pukhtuns. 109 110 [J.R.S.P., Vol. 51, No. 1, January – June, 2014] The diverging beliefs and subsequent debates between Mian Noor and Khushal Khan also contributed to the failure of Khushal Khan’s mission in Swat. -

Inter Cluster Assessment Mission to Orakzai Agency

ABSTRACT The Report includes the findings of an Inter-Cluster Assessment mission to the de-notified areas of Orakzai Agency. The mission held meetings with Government officials and IDPs and visited some of the villages to which the IDPs will return. The mission found conditions in the Agency conducive for returns, recommends support to the returns process, except to four villages where there is a risk of landmines mines. Inter Cluster Assessment Mission to Orakzai Agency 19 September 2015 Compiled by OCHA Pakistan Contents 1. Background .................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Mission Objectives ...................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 2 4. Challenges ................................................................................................................................................... 3 5. Meeting with political authorities and FDMA ........................................................................................... 3 6. Cluster specific findings .............................................................................................................................. 3 a. Community Restoration ......................................................................................................................... -

Check List of Heteroptera of Parachinar (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), Pakistan

INT. J. BIOL. BIOTECH., 9 (3): 327-330, 2012. CHECK LIST OF HETEROPTERA OF PARACHINAR (KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA), PAKISTAN Rafiq Hussain and Rukhsana Perveen Department of Zoology University of Karachi, Karachi 75270, Pakistan. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT An investigation was carried out on Heteroptera fauna of Parachinar, located in west of Peshawar (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan).Twenty one species belonging eighteen genera from five different families (Pentatomidae, Lygaeidae, Reduviidae, Pyrrhocoridae and Belostomatidae) were collected from 2007-2010. The specimens were identified through fauna of British India and pertinent literature. Pentatomidae is dominant family having greater number of specimens. The species listed below are new record from the studied area. All the specimens have been deposited in the Zoological Museum University of Karachi. Key Words: Faunistic, Heteroptera, Parachinar, First Record. INTRODUCTION The first mention of the true bugs (Hemiptera : Heteroptera) of Pakistan came with the series of Distant fauna of British India including Ceylon and Burma (1902,1904,1908). Since that time the publication of Ahmad (1979, 1980,1981 ), Ahmad et al ( 1986 ), Ahmad and Kamaluddin (1985, 1989 ), Ahmad and Perveen ( 1983 ), Abbasi (1986), Ahmad and McPherson (1990), Ahmad and Zahid (2004) , Memon, Ahmad and Kamaluddin (2004) has added significant part of Heteroptera species of Pakistan. Parachinar is an agricultural region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The climate of this region is cold and hard with annual rain fall of 245-250mm. Wheat, Rice, Maize, Sun-flower and vegetables e.g. potato, tomato, Pea, turnip, ladyfinger, onion, garlic and fruits such as apple, pear, apricot, walnut are the important crops and fruits of this locality.