UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Babylonian Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud translated by MICHAEL L. RODKINSON Book 10 (Vols. I and II) [1918] The History of the Talmud Volume I. Volume II. Volume I: History of the Talmud Title Page Preface Contents of Volume I. Introduction Chapter I: Origin of the Talmud Chapter II: Development of the Talmud in the First Century Chapter III: Persecution of the Talmud from the destruction of the Temple to the Third Century Chapter IV: Development of the Talmud in the Third Century Chapter V: The Two Talmuds Chapter IV: The Sixth Century: Persian and Byzantine Persecution of the Talmud Chapter VII: The Eight Century: the Persecution of the Talmud by the Karaites Chapter VIII: Islam and Its Influence on the Talmud Chapter IX: The Period of Greatest Diffusion of Talmudic Study Chapter X: The Spanish Writers on the Talmud Chapter XI: Talmudic Scholars of Germany and Northern France Chapter XII: The Doctors of France; Authors of the Tosphoth Chapter XIII: Religious Disputes of All Periods Chapter XIV: The Talmud in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries Chapter XV. Polemics with Muslims and Frankists Chapter XVI: Persecution during the Seventeenth Century Chapter XVII: Attacks on the Talmud in the Nineteenth Century Chapter XVIII. The Affair of Rohling-Bloch Chapter XIX: Exilarchs, Talmud at the Stake and Its Development at the Present Time Appendix A. Appendix B Volume II: Historical and Literary Introduction to the New Edition of the Talmud Contents of Volume II Part I: Chapter I: The Combination of the Gemara, The Sophrim and the Eshcalath Chapter II: The Generations of the Tanaim Chapter III: The Amoraim or Expounders of the Mishna Chapter IV: The Classification of Halakha and Hagada in the Contents of the Gemara. -

Keter As a Jewish Political Symbol

KETER AS A JEWISHPOLITICAL SYMBOL: ORIGINS AND IMPLICATIONS Stuart A. Cohen The use of theHebrew term keter (lit. "crown") to describe agencies of Jewish autonomous rule is first apparent in tanna'itic texts, and especially inMishrtah, Avot 4:13. This article examines the reasons for that innova tion, and examines the categories of rulership to which the term was ap plied. It is suggested that keter reflected an identifiable notion of "sovereignty" and its exercise. In early rabbinic usage, it became a vehicle which conveyed a unique view of the constitutionally correct ordering of Jewish political life. The only Old Testament references to the royal headdress desig nated the keter (lit. "crown") are to be found in the Book of Esther, where the term describes a non-Jewish (Persian) emblem of distinction. Admittedly, the root KTR is indigenously Hebrew; it occurs in Judges 20:43 (meaning "to surround") and in IKings 7:16,17; Jer. 52:22 (meaning "cornice"). But not until the early rabbinic period does the term appear a to have been used to depict the crown as specifically Jewish badge of office. Once that step had been taken, however, the process of semantic accommodation seems to have been both swift and extensive. For one thing, authors of early rabbinic texts frequently (although not invari ably) employed the noun keter as a primary depiction of the royal headdress, preferring it to other crown synonyms which were of more distinguished biblical pedigree. Secondly, and more interestingly, they considerably modified and extended the application of that term it self. As early as Mishnah, Avot 4:13, keter no longer designated (as it did in Esther) exclusively royal authority. -

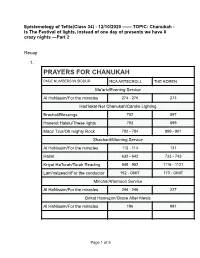

Chanukah Is the Festival of Lights Instead of One Day Of

Epistemology of Tefila(Class 34) - 12/10/2020 —— TOPIC: Chanukah - is The Festival of lights, instead of one day of presents we have 8 crazy nights —Part 2 Recap 1. PRAYERS FOR CHANUKAH PAGE NUMBERS IN SIDDUR RCA ARTSCROLL THE KOREN Ma’ariv/Evening Service Al HaNissim/For the miracles 274 - 276 273 Had’lakat Ner Chanukah/Candle Lighting Brachot/Blessings 782 897 Hanerot Halalu/These lights 782 899 Maoz Tzur/Oh mighty Rock 782 - 784 899 - 901 Shacharit/Morning Service Al HaNissim/For the miracles 112 - 114 131 Hallel 632 - 642 733 - 743 Kriyat HaTorah/Torah Reading 948 - 952 1116 - 1121 Lam’natzeach/For the conductor 152 - OMIT 173 - OMIT Mincha/Afternoon Service Al HaNissim/For the miracles 244 - 246 227 Birkat Hamazon/Grace After Meals Al HaNissim/For the miracles 186 981 Page 1 of 5 2. Main addition is Al HaNissim/For the miracles in our Amidah for Ma’ariv, Shacharit, Mincha, and Birkat Hamazon. 3. We light candles every night, from left to right with a bracha starting with one and adding one additional candle each night until we have 8. 4. We sing the hymn Haneirot halalu while we light the candles and remember that the candles remind us of the miracle and are holy. 5. During the time of lighting canldles we take the time to off from our work, to rest, sing songs, play dreidel, and educate our children about the miracle. Class Strategy 1. Maoz Tzur/O mighty Rock — (RCA Artscroll page 782 -784, The Koren page 899 - 901) Rav Munk(page 409) after all the lights are burning it is customary to sing Maoz Tzur/O mighty Rock which was written Mordechai Ben Yitchak before 1250 but mor than that no exact details of the author are known. -

25D the Soncino Babylonian Talmud

KESUVOS – 78a-112a 25d The Soncino Babylonian Talmud KKEETTHHUUBBOOTTHH Book IV Folios 78a-112a CHAPTERS VIII-XIII TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH NOTES BY R A B B I D R . S A M U E L DAICHES Barrister at Law AND R E V . D R . I S R A E L W. SLOTKI, M.A., Litt.D. UNDER THE EDITORSHIP OF R A B B I D R I. EPSTEIN B.A., Ph.D., D. Lit. Reformatted by Reuven Brauner, Raanana 5772 www.613etc.com 1 KESUVOS – 78a-112a Kethuboth 78a VOID; [PROPERTY, HOWEVER,] WHICH IS UNKNOWN TO THE HUSBAND SHE MAY CHAPTER VIII NOT SELL, BUT IF SHE HAS SOLD IT OR GIVEN IT AWAY HER ACT IS LEGALLY MISHNAH . IF A WOMAN CAME INTO THE VALID. POSSESSION 1 OF PROPERTY BEFORE SHE WAS BETROTHED, BETH SHAMMAI AND GEMARA . What is the essential difference BETH HILLEL AGREE THAT SHE MAY 2 between the first clause 14 in which they 15 do SELL IT OR GIVE IT AWAY AND HER ACT IS not differ and the succeeding clause 16 in LEGALLY VALID. IF SHE CAME INTO THE which they differ? 17 — The school of R. POSSESSION OF THE PROPERTY AFTER Jannai replied: In the first clause it was into SHE WAS BETROTHED, BETH SHAMMAI her possession that the property had come; 18 SAID: SHE MAY SELL IT, 2 AND BETH in the succeeding clause 16 the property came HILLEL SAID: SHE MAY NOT SELL IT; 2 BUT into his possession. 19 If, however, [it is BOTH AGREE THAT IF SHE HAD SOLD IT maintained] that the property 'came into his OR GIVEN IT AWAY HER ACT IS LEGALLY possession' why is HER ACT LEGALLY VALID. -

The Gehenna Controversy

The Gehenna Controversy Walter Balfour, Bernard Whitman 1833-1834 Contents Contents . i An Inquiry into the Scriptural Import of the words Sheol, Hades, Tartarus and Gehenna, translated Hell in the Common English Version, by Walter Balfour 1 Facts stated respecting Gehenna, showing that it does not express a place of endless punishment in the New Testament. 1 All the texts in which Gehenna occurs, considered. 6 Additional facts stated, proving that Gehenna was not used by the sacred writers to express a place of endless misery. 41 Friendly letters to a Universalist on divine rewards and punish- ments: Letter VI, by Bernard Whitman 59 A letter to the Rev. Bernard Whitman, on the term Gehenna, by Walter Balfour 77 Explanation of Matthew v. 29, 30, and the similar Texts, by Hosea Ballou 139 i An Inquiry into the Scriptural Import of the words Sheol, Hades, Tartarus and Gehenna, translated Hell in the Common English Version Walter Balfour Revised, with essays and notes, by Otis A. Skinner Boston: published by A. Tompkins. 1854. SECTION II: Facts stated respecting Gehenna, showing that it does not express a place of endless punishment in the New Testament. Before we consider the texts, where Gehenna occurs in the New Testament, it is of importance to notice the following facts. They have been altogether overlooked, or but little attended to in discussions on this subject. 1st. The term Gehenna is not used in the Old Testament to designate a place of endless punishment. Dr. Campbell declares positively that it has no such mean- ing there. All agree with him; and this should lead to careful inquiry whether in the New Testament it can mean a place of endless misery. -

Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands

Out of the Shtetl Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands NANCY SINKOFF OUT OF THE SHTETL Program in Judaic Studies Brown University Box 1826 Providence, RI 02912 BROWN JUDAIC STUDIES Series Editors David C. Jacobson Ross S. Kraemer Saul M. Olyan Number 336 OUT OF THE SHTETL Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands by Nancy Sinkoff OUT OF THE SHTETL Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands Nancy Sinkoff Brown Judaic Studies Providence Copyright © 2020 by Brown University Library of Congress Control Number: 2019953799 Publication assistance from the Koret Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Brown Judaic Studies, Brown University, Box 1826, Providence, RI 02912. In memory of my mother Alice B. Sinkoff (April 23, 1930 – February 6, 1997) and my father Marvin W. Sinkoff (October 22, 1926 – July 19, 2002) CONTENTS Acknowledgments....................................................................................... ix A Word about Place Names ....................................................................... xiii List of Maps and Illustrations .................................................................... xv Introduction: -

Pachad David

Ha’azinu Weekly Bulletin on the Parshah September 23rd 2017 3rd of Tishri 5778 717 Pachad David Published by Mosdot Orot Chaim U’Moshe in Israel Under the auspices of Moreinu v’Rabbeinu Hagaon Hatzaddik Rabbi David Chananya Pinto, shlita Son of the tzaddik and miracle-worker Rabbi Moshe Ahron Pinto, zt”l, and grandson of the holy tzaddik and miracle-worker Rabbi Chaim Pinto, zy”a MaskilMASKIL L'David LÉDAVID Weekly talk on the Parshah given by Moreinu v’Rabbeinu Hagaon Hatzaddik Rabbi David Chananya Pinto, shlita Man’s Mission in This World “Listen, O heavens, and I will speak! of Israel and the World to Come.” The suffering creates the bond to Eretz Yisrael by causing them And let the earth hear the words of to strengthen their spiritual (heavenly) component my mouth!” and weakening the physical (earthly) portion. In (Devarim 32:1) this way they will merit the Land of Israel, where The commentaries ask, what is the connection Hashem’s “Eyes” are always focused. between the heavens and earth and the admon- Chazal say (Berachot 33b), “Everything is in ishment for Am Yisrael? the Hand of Heaven except the fear of Heaven.” There are those who explain that the heavens This sounds surprising, since if everything is in and earth are an allegory to man; man is com- the Hands of Heaven, meaning all great things posed of two parts – the upper part, which is and small things one needs, whether physical or spiritual, and the lower part, which is physical. spiritual, then how come the thing that is most This is similar to the account of Yiravam ben Nevat, Heavenly, which is the fear of Heaven is not in the Chevrat Pinto NYC when Hashem “seized” him and urged him, “Re- Hands of Heaven? 207 West 78th Street • New York NY 10024 • U.S.A pent, then I, you, and the son of Yishai [i.e. -

With Letters of Light: Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Early Jewish

With Letters of Light rwa lç twytwab Ekstasis Religious Experience from Antiquity to the Middle Ages General Editor John R. Levison Editorial Board David Aune · Jan Bremmer · John Collins · Dyan Elliott Amy Hollywood · Sarah Iles Johnston · Gabor Klaniczay Paulo Nogueira · Christopher Rowland · Elliot R. Wolfson Volume 2 De Gruyter With Letters of Light rwa lç twytwab Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Early Jewish Apocalypticism, Magic, and Mysticism in Honor of Rachel Elior rwayla ljr Edited by Daphna V. Arbel and Andrei A. Orlov De Gruyter ISBN 978-3-11-022201-2 e-ISBN 978-3-11-022202-9 ISSN 1865-8792 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data With letters of light : studies in the Dead Sea scrolls, early Jewish apocalypti- cism, magic and mysticism / Andrei A. Orlov, Daphna V. Arbel. p. cm. - (Ekstasis, religious experience from antiquity to the Middle Ages;v.2) Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “This volume offers valuable insights into a wide range of scho- larly achievements in the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish apocalypti- cism, magic, and mysticism from the Second Temple period to the later rabbinic and Hekhalot developments. The majority of articles included in the volume deal with Jewish and Christian apocalyptic and mystical texts constituting the core of experiential dimension of these religious traditions” - ECIP summary. ISBN 978-3-11-022201-2 (hardcover 23 x 15,5 : alk. paper) 1. Dead Sea scrolls. 2. Apocalyptic literature - History and criticism. 3. Jewish magic. 4. Mysticism - Judaism. 5. Messianism. 6. Bible. O.T. - Criticism, interpretation, etc. 7. Rabbinical literature - History and criticism. -

Rabbis on the Road: Exposition En Route in Classical Rabbinic Texts

Rabbis on the Road: Exposition En Route in Classical Rabbinic Texts by Ruth Ellen Haber A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Dina Stein Professor Michael Nylan Fall 2014 Abstract Rabbis on the Road: Exposition En Route in Classical Rabbinic Texts by Ruth Ellen Haber Joint Doctor of Philosophy in Jewish Studies with the Graduate Theological Union University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair Throughout classical rabbinic texts, we find accounts of sages expounding Scripture or law, while “walking on the road.” We may well wonder why we find these sages in transit, rather than in the usual sites of Torah study, such as the bet midrash (study house) or ʿaliyah (upper story of a home). Indeed, in this corpus of texts, sages normally sit to study; the two acts are so closely associated, that the very word “sitting” is synonymous with a study session or academy. Moreover, throughout the corpus, “the road” is marked as the site of danger, disruption and death. Why then do these texts tell stories of sages expounding en route? In seeking out the rabbinic road, I find that, against these texts’ pervasive notion of travel danger runs another, competing motif: the road as the proper – even necessary – site of Torah study. Tracing the genealogy of the road exposition (or “road derasha”), I find it rooted in traditional Wisdom texts, which have been adapted to form a new, “literal” metaphor. -

Yirat Shamayim As Jewish Paideia

Marc D. Stern Robert S. Hirt, Series Editor OF Awe of God 08 draft 07 balanced.indd iii 9/17/2008 8:52:54 AM THE ORTHODOX FORUM The Orthodox Forum, initially convened by Dr. Norman Lamm, Chancellor of Yeshiva University, meets each year to consider major issues of concern to the Jewish community. Forum participants from throughout the world, including academicians in both Jewish and secular fields, rabbis, rashei yeshivah, Jewish educators, and Jewish communal professionals, gather in conference as a think tank to discuss and critique each other’s original papers, examining different aspects of a central theme. The purpose of the Forum is to create and disseminate a new and vibrant Torah literature addressing the critical issues facing Jewry today. The Orthodox Forum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Joseph J. and Bertha K. Green Memorial Fund at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary established by Morris L. Green, of blessed memory. The Orthodox Forum Series is a project of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Yeshiva University OF Awe of God 08 draft 07 balanced.indd ii 9/17/2008 8:52:53 AM In Memory of My Parents Herman and Marion Stern Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yirat shamayim : the awe, reverence, and fear of God / edited by Marc D. Stern. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-60280-037-3 1. Fear of God – Judaism. 2. Orthodox Judaism. I. Stern, Marc D. BM645.F4Y57 2008 296.3’11 – dc22 * * * Distributed by KTAV Publishing House, Inc. 930 Newark Avenue Jersey City, NJ 07306 Tel. -

Proquest Dissertations

453 FUNDAMENTAL JEWISH EDUCATIONAL IDEALS A Thesis Submitted to the University of Ottawa by Julius Berger in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1950 LkMAfcl£$ %, ^ '»• . *ify 0* X UMI Number: DC53973 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53973 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Prefatory Note It is customary to add a prefatory note to the beginning and a concluding statement to the end of a dissertation. Perhaps, the basis for it is the maxim that "ideas are most readily conveyed to others when you tell them what you are going to tell them, and then tell them what you have told them." This survey offers a contribution to an under standing of the function of Jewish education. The transmission of Jewish values, animated by definite ideals, had for its conscious purpose of arousing religious impulses and ethical tendencies within the hearts and minds of the people. A mere glance at the table of contents will show that the educational ideals described are meant to give support and sanction to the teaching that the history of mankind can be directed into channels making for social, intellect ual, religious, national and international progress. -

Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity. Part I Palestine 330 BCE

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel und Peter Schäfer 91 ARTIBUS Tal Ilan Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity Parti Palestine 330 BCE - 200 CE Mohr Siebeck Tal Ilan, born 1956; 1991 Ph.D. on Jewish Women in Greco-Roman Palestine at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; since 1996 lecturer at the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, Jerusalem; 1992-93 Guest Professor at Harvard; 1995 at Yale and at the Freie Universität Berlin; 1997 at the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York; 1998 at Frankfurt University. CÌP-Titelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek itan. Tal: Lexicon of Jewish names in late antiquity / Tal Ilan. - Tübingen : Mohr Siebeck Pt. 1. Palestine 330 BCE-200 CE. - 2002 (Texts and studies in ancient Judaism ; 91) ISBN 3-16-147646-8 © 2002 by J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O.Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen, printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany ISSN 0721-8753 Dedicated to Yossi Garfinkel - my best friend Acknowledgement This project began as a seminar paper in Prof. Lee Levine's archaeological- historical class on the Hcrodian period at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1982. Levine was interested in investigating the use of Greek names by Jewish aristocrats during the Herodian period.