Dendrobium (Orchidaceae): to Split Or Not to Split?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orchidarium Es Una Revista Editada Por El Parque Botánico Y Orquidario De Estepona

Orchidar ium Revista trimestral del Orquidario de Estepona ISSN 2386-6497 Nº1 Año 2015. Enero - Febrero - Marzo Foto de portada: No podíamos comenzar esta andadura sin una foto del orquidario que nos sirve de referencia; nos referimos al orqui- dario de Estepona. El edificio, diseñado por los arquitectos Gustavo y Fernando Gómez Huete, conjuga elementos de vanguardia con otros clá- sicos y asociados a este tipo de construcciones. Pero tampoco se ha olvidado de la funcionalidad. La prosperidad de sus colecciones será la mejor prueba. Contenido página 2 Editorial página 3 Orquidario de Estepona: Presentación. Por Manuel Lucas página 8 Género del mes: Una primera vista del género Bulbophyllum. Por Manuel Lucas página 17 Ficha de cultivo: Bullbophyllum wendlandianum. Por Manuel Lucas página 19 Tema: Mecanismos de Polinización de las Orquídeas. Por Maria Elena Gudiel página 25 Darwiniana: Louis-Marie Aubert Du Petit-Thouars. Por Manuel Lucas página 28 Florilegium página 31 Ficha de cultivo: Bulbophyllum falcatum. Por Manuel Lucas página 35 Orquídeas de Europa: el género Ophrys. Por Alberto Martínez página 40 Opinión: Cultivo general, reflexión elemental. Por Péter Szabó página 42 Orquilocuras: El curso. Por Antonio Franco página 44 Información y calendario de actividades Orchidarium es una revista editada por el Parque Botánico y Orquidario de Estepona. Domicilio: Calle Terraza s/n 29680-Estepona (Málaga) Teléfono de contacto: 622646407. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Dirección, diseño, y maquetación: Manuel Lucas García. Equipo editorial: Manuel Lucas García y Alberto Martínez. Nuestro archivo fotográfico se sirve de los colaboradores externos, con agradecimiento: Daniel Jiménez (www.flickr.com/photos/costarica1/) Emilio E. -

Dendrobium Kingianum Bidwill Ex Lindl

Volume 24: 203–232 ELOPEA Publication date: 19 May 2021 T dx.doi.org/10.7751/telopea14806 Journal of Plant Systematics plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/Telopea • escholarship.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/TEL • ISSN 0312-9764 (Print) • ISSN 2200-4025 (Online) A review of Dendrobium kingianum Bidwill ex Lindl. (Orchidaceae) with morphological and molecular- phylogenetic analyses Peter B. Adams1,2, Sheryl D. Lawson2, and Matthew A.M. Renner 3 1The University of Melbourne, School of BioSciences, Parkville 3010, Victoria 2National Herbarium of Victoria, Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, Birdwood Ave., Melbourne 3004, Victoria 3National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney 2000, New South Wales Author for correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Populations of Dendrobium kingianum Bidwill ex Lindl. from near Newcastle, New South Wales to southern and central west Queensland and encompassing all regions of the distribution were studied using field observations, morphometric analysis and nrITS sequences. A total of 281 individuals were used to construct regional descriptions of D. kingianum and 139 individuals were measured for 19 morphological characters, and similarities and differences among specimens summarised using multivariate statistical methods. Patterns of morphological variation within D. kingianum are consistent with a single variable species that expresses clinal variation, with short-growing plants in the south and taller plants in the northern part of the distribution. The nrITS gene tree suggests two subgroups within D. kingianum subsp. kingianum, one comprising northern, the other southern individuals, which may overlap in the vicinity of Dorrigo, New South Wales. The disjunct D. kingianum subsp. carnarvonense Peter B. -

Australia Lacks Stem Succulents but Is It Depauperate in Plants With

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Australia lacks stem succulents but is it depauperate in plants with crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM)? 1,2 3 3 Joseph AM Holtum , Lillian P Hancock , Erika J Edwards , 4 5 6 Michael D Crisp , Darren M Crayn , Rowan Sage and 2 Klaus Winter In the flora of Australia, the driest vegetated continent, [1,2,3]. Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), a water- crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), the most water-use use efficient form of photosynthesis typically associated efficient form of photosynthesis, is documented in only 0.6% of with leaf and stem succulence, also appears poorly repre- native species. Most are epiphytes and only seven terrestrial. sented in Australia. If 6% of vascular plants worldwide However, much of Australia is unsurveyed, and carbon isotope exhibit CAM [4], Australia should host 1300 CAM signature, commonly used to assess photosynthetic pathway species [5]. At present CAM has been documented in diversity, does not distinguish between plants with low-levels of only 120 named species (Table 1). Most are epiphytes, a CAM and C3 plants. We provide the first census of CAM for the mere seven are terrestrial. Australian flora and suggest that the real frequency of CAM in the flora is double that currently known, with the number of Ellenberg [2] suggested that rainfall in arid Australia is too terrestrial CAM species probably 10-fold greater. Still unpredictable to support the massive water-storing suc- unresolved is the question why the large stem-succulent life — culent life-form found amongst cacti, agaves and form is absent from the native Australian flora even though euphorbs. -

Review of Selected Literature and Epiphyte Classification

--------- -- ---------· 4 CHAPTER 1 REVIEW OF SELECTED LITERATURE AND EPIPHYTE CLASSIFICATION 1.1 Review of Selected, Relevant Literature (p. 5) Several important aspects of epiphyte biology and ecology that are not investigated as part of this work, are reviewed, particularly those published on more. recently. 1.2 Epiphyte Classification and Terminology (p.11) is reviewed and the system used here is outlined and defined. A glossary of terms, as used here, is given. 5 1.1 Review of Selected, Relevant Li.terature Since the main works of Schimper were published (1884, 1888, 1898), particularly Die Epiphytische Vegetation Amerikas (1888), many workers have written on many aspects of epiphyte biology and ecology. Most of these will not be reviewed here because they are not directly relevant to the present study or have been effectively reviewed by others. A few papers that are keys to the earlier literature will be mentioned but most of the review will deal with topics that have not been reviewed separately within the chapters of this project where relevant (i.e. epiphyte classification and terminology, aspects of epiphyte synecology and CAM in the epiphyt~s). Reviewed here are some special problems of epiphytes, particularly water and mineral availability, uptake and cycling, general nutritional strategies and matters related to these. Also, all Australian works of any substance on vascular epiphytes are briefly discussed. some key earlier papers include that of Pessin (1925), an autecology of an epiphytic fern, which investigated a number of factors specifically related to epiphytism; he also reviewed more than 20 papers written from the early 1880 1 s onwards. -

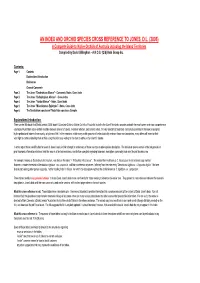

Jones Cross 2006 Index

AN INDEX AND ORCHID SPECIES CROSS REFERENCE TO JONES, D.L. (2006) A Complete Guide to Native Orchids of Australia including the Island Territories Compiled by David Gillingham - A.N.O.S. (Qld) Kabi Group Inc. Contents: Page 1: Contents Explanations/Introduction References General Comments Page 2: The Jones "Dendrobium Alliance" - Comments, Notes, Cross Index Page 3: The Jones "Bulbophyllum Alliance" - Cross Index Page 4: The Jones "Vanda Alliance" - Notes, Cross Index Page 5: The Jones "Miscellaneous Epiphytes" - Notes, Cross Index Page 6: The Dendrobium speciosum/Thelychiton speciosus Complex Explanations/Introduction: There can be little doubt that David Jones's (2006) book A Complete Guide to Native Orchids of Australia including the Island Territories provides probably the most current and most comprehensive coverage of Australia's native orchids available between one set of covers. However whether, and to what extent, the very substantial taxonomic restructure presented in the book is accepted by the professional botanical community, only time will tell. In the meantime, while many orchid growers will enthusiastically embrace these new taxonomies, many others will exercise their valid right to continue labelling their orchids using the older taxa, waiting for the dust to settle on the scientific debate. In either regard there are difficulties for users of Jones's book, in their attempt to relate many of these new taxa to older species descriptors. The individual species entries in the text provide no prior taxonomic information whatever; and the index is of limited assistance, and far from complete regarding taxonomic descriptors commonly used over the past decade or so. -

Dendrobium Moiorum (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae), a New Species of Dendrobium Section Diplocaulobium from West Papua, Indonesia

Phytotaxa 430 (2): 142–146 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.430.2.5 Dendrobium moiorum (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae), a new species of Dendrobium section Diplocaulobium from West Papua, Indonesia REZA SAPUTRA1, MARK ARCEBAL K. NAIVE2, JIMMY FRANS WANMA3 & ANDRÉ SCHUITEMAN4 1West Papua Natural Resources Conservation Agency (Balai Besar KSDA Papua Barat), Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Indonesia. Jalan Klamono KM 16, Sorong, West Papua Province, Indonesia; E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, College of Science and Mathematics, Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology, Iligan City, Lanao del Norte, Philippines 3University of Papua, Manokwari, West Papua Province, Indonesia 4Science Directorate, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AB, UK Abstract Dendrobium moiorum Saputra, Schuit., Wanma & Naive (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae; Dendrobieae), a new endemic species from West Papua, Indonesia, is described and illustrated. The new species resembles Dendrobium isthmiferum and the diagnostic differences are discussed. Information on distribution, ecology, phenology and conservation status are provided. Keywords: endemic, Papuasia, taxonomy, Sorong Nature Recreation Park Introduction Described by Swartz (1799: 82), Dendrobium belongs to the tribe Malaxideae, subtribe Dendrobiinae (Chase et al., 2015), and is the second largest orchid genus encompassing about 1600–1800 species. This genus consists of epiphytic, occasionally lithophytic or rarely terrestrial herbs distributed from Sri Lanka throughout tropical Asia and the Pacific region, north to Japan, east to Tahiti and south to New Zealand (Schuiteman & Adams, 2014; Ormerod, 2017). According to Ormerod & Juswara (2019), the number of species belonging to the genus Dendrobium in Indonesia is uncertain but is probably around 800 species and many undoubtedly still await discovery. -

Molecular Identification and Evaluation of the Genetic Diversity

biology Article Molecular Identification and Evaluation of the Genetic Diversity of Dendrobium Species Collected in Southern Vietnam 1, , 2, 2 2 Nhu-Hoa Nguyen * y, Huyen-Trang Vu y, Ngoc-Diep Le , Thanh-Diem Nguyen , Hoa-Xo Duong 3 and Hoang-Dung Tran 2,* 1 Faculty of Biology, Ho Chi Minh City University of Education, 280 An Duong Vuong Street, Ward 4, District 5, Ho Chi Minh 72711, Vietnam 2 Faculty of Biotechnology, Nguyen Tat Thanh University, 298A-300A Nguyen Tat Thanh Street, Ward 13, District 4, Ho Chi Minh 72820, Vietnam; [email protected] (H.-T.V.); [email protected] (N.-D.L.); [email protected] (T.-D.N.) 3 Biotechnology Center of Ho Chi Minh City, 2374 Highway 1, Quarter 2, Ward Trung My Tay, District 12, Ho Chi Minh 71507, Vietnam; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.-H.N.); [email protected] (H.-D.T.) These authors contributed equally to the works. y Received: 15 March 2020; Accepted: 9 April 2020; Published: 10 April 2020 Abstract: Dendrobium has been widely used not only as ornamental plants but also as food and medicines. The identification and evaluation of the genetic diversity of Dendrobium species support the conservation of genetic resources of endemic Dendrobium species. Uniquely identifying Dendrobium species used as medicines helps avoid misuse of medicinal herbs. However, it is challenging to identify Dendrobium species morphologically during their immature stage. Based on the DNA barcoding method, it is now possible to efficiently identify species in a shorter time. In this study, the genetic diversity of 76 Dendrobium samples from Southern Vietnam was investigated based on the ITS (Internal transcribed spacer), ITS2, matK (Maturase_K), rbcL (ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase large subunit) and trnH-psbA (the internal space of the gene coding histidine transfer RNA (trnH) and gene coding protein D1, a polypeptide of the photosystem I reaction center (psaB)) regions. -

Botanical Inventory of the Proposed Ta'u Unit of the National Park of American Samoa

Cooperative Natiad Park Resou~cesStudies Unit University of Hawaii at Manoa Department of Botany 3 190 Made Way Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 (808) 956-8218 Technical Report 83 BOTANICAL INVENTORY OF THE PROPOSED TA'U UNIT OF THE NATIONAL PARK OF AMERICAN SAMOA Dr. W. Arthur Whistler University of Hawai'i , and National Tropical Botanical Garden Lawai, Kaua'i, Hawai'i NatidPark Swice Honolulu, Hawai'i CA8034-2-1 February 1992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank Tim Motley. Clyde Imada, RdyWalker. Wi. Char. Patti Welton and Gail Murakami for their help during the field research catried out in December of 1990 and January of 1991. He would also like to thank Bi Sykes of the D.S.I.R. in Chtistchurch, New Zealand. fur reviewing parts of the manuscript, and Rick Davis and Tala Fautanu fur their help with the logistics during the field work. This research was supported under a coopemtive agreement (CA8034-2-0001) between the University of Hawaii at Man08 and the National Park !&mice . TABLE OF CONTENTS I . INTRODUCTION (1) The Geography ...........................................................................................................1 (2) The Climate .................................................................................................................1 (3) The Geology............................................................................................................... 1 (4) Floristic Studies on Ta'u .............................................................................................2 (5) Vegetation -

Bulbophyllum Trongsaense (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae: Dendrobieae), a New Species from Bhutan

Phytotaxa 436 (1): 085–091 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.436.1.9 Bulbophyllum trongsaense (Orchidaceae: Epidendroideae: Dendrobieae), a new species from Bhutan PHUB GYELTSHEN1*, DHAN BAHADUR GURUNG2 & PANKAJ KUMAR3* 1Department of Forest and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, Trongsa, Bhutan. 2College of Natural Resources, Royal University of Bhutan, Lobesa, Bhutan. 3Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden, Lam Kam Road, Lam Tsuen, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong S.A.R., P.R. China. *For correspondence: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Bulbophyllum trongsaense is described as a new species from Trongsa district of Bhutan. Detailed morphological description, distribution, phenology, ecology and colour photographs are provided along with comparison with B. amplifolium to which it shows closest affinity. Keywords: Bulbophyllum amplifolium, B. nodosum, Endangered Introduction Orchidaceae is the largest and most diverse family of flowering plants (Pearce & Cribb 2002, Gurung 2006, Chase et al. 2015) consisting over 28,000 species in 736 genera with new species increasing day by day (Christenhusz & Byng 2016). Orchids occupy almost all habitats on earth except the glaciers; however, they show highest diversity in the tropics (Gurung 2006). Bhutan, the part of Eastern Himalayan Hotspot is home to rich flora and fauna. Pearce & Cribb (2002) recorded 369 species for Bhutan and about 579 species from other Himalayan regions, but this number is surely an underestimate and Bhutan is likely to harbor around 500 species as many parts of the country are still under surveyed (Pearce & Cribb 2002, Gurung 2006). -

Orchidaceae) from Argentina and Uruguay

Phytotaxa 175 (3): 121–132 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.175.3.1 A new paludicolous species of Malaxis (Orchidaceae) from Argentina and Uruguay JOSÉ A. RADINS1, GERARDO A. SALAZAR2,5, LIDIA I. CABRERA2, ROLANDO JIMÉNEZ-MACHORRO3 & JOÃO A. N. BATISTA4 1Dirección de Biodiversidad, Ministerio de Ecología y Recursos Naturales Renovables, Calle San Lorenzo 1538, Código Postal 3300, Posadas, Misiones, Argentina 2Departamento de Botánica, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado Postal 70-367, 04510 Mexico City, Distrito Federal, Mexico 3Herbario AMO, Montañas Calizas 490, Lomas de Chapultepec, 11000 Mexico City, Distrito Federal, Mexico 4Departamento de Botânica, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Caixa Postal 486, 31270−910 Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil 5Corresponding autor; e-mail [email protected] Abstract Malaxis irmae, a new orchid species from the Paraná and Uruguay river basins in northeast Argentina and Uruguay, is de- scribed and illustrated. It is similar in size and overall floral morphology to Malaxis cipoensis, a species endemic to upland rocky fields on the Espinhaço range in Southeastern Brazil, which is its closest relative according to a cladistics analysis of nuclear (ITS) and plastid (matK) DNA sequences presented here. However, M. irmae is distinguished from M. cipoensis by inhabiting lowland marshy grasslands, possessing 3−5 long-petiolate leaves per shoot (vs. 2 shortly petiolate leaves), cy- lindrical raceme (vs. corymbose), pale green flowers (vs. green-orange flowers) and less prominent basal labellum lobules. -

The Rare Plants of Samoa JANUARY 2011

The Rare Plants of Samoa JANUARY 2011 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 2 BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 2 The Rare Plants of Samoa Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2011. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 2: The Rare Plants of Samoa. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Author: Art Whistler, Isle Botanica, Honolulu, Hawai’i Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Series Editors: James Atherton and Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. ISBN 978-982-9130-02-0 © 2011 Conservation International All rights reserved. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, CI empowers societies to responsibly and sustainably care for nature for the well-being of humanity This publication is available electronically from Conservation International’s website: www.conservation.org ABOUT THE BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES This document is part of a technical report series on conservation projects funded by the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and the Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific). The main purpose of this series is to disseminate project findings and successes to a broader audience of conservation professionals in the Pacific, along with interested members of the public and students. -

Network Scan Data

Selbyana 29(1): 69-86. 2008. THE ORCHID POLLINARIA COLLECTION AT LANKESTER BOTANICAL GARDEN, UNIVERSITY OF COSTA RICA FRANCO PUPULIN* Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 1031-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica, CA Angel Andreetta Research Center on Andean Orchids, University Alfredo Perez Guerrero, Extension Gualaceo, Ecuador Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA, USA The Marie Selby Botanical Gardens, Sarasota, FL, USA Email: [email protected] ADAM KARREMANS Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica. P.O. Box 1031-7050 Cartago, Costa Rica, CA Angel Andreetta Research Center on Andean Orchids, University Alfredo Perez Guerrero, Extension Gualaceo, Ecuador ABSTRACT. The relevance of pollinaria study in orchid systematics and reproductive biology is summa rized. The Orchid Pollinaria Collection and the associate database of Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica, are presented. The collection includes 496 pollinaria, belonging to 312 species in 94 genera, with particular emphasis on Neotropical taxa of the tribe Cymbidieae (Epidendroideae). The associated database includes digital images of the pollinaria and is progressively made available to the general public through EPIDENDRA, the online taxonomic and nomenclatural database of Lankester Botanical Garden. Examples are given of the use of the pollinaria collection by researchers of the Center in a broad range of systematic applications. Key words: Orchid pollinaria, systematic botany, pollination biology, orchid pollinaria collection,