1 Piia Leino HEAVEN Finnish Original

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

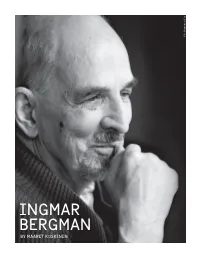

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

Woody Loves Ingmar

1 Woody loves Ingmar Now that, with Blue Jasmine , Woody Allen has come out … … perhaps it’s time to dissect all his previous virtuoso creative adapting. I’m not going to write about the relationship between Vicky Christina Barcelona and Jules et Jim . ————— Somewhere near the start of Annie Hall , Diane Keaton turns up late for a date at the cinema with Woody Allen, and they miss the credits. He says that, being anal, he has to see a film right through from the very start to the final finish, so it’s no go for that movie – why don’t they go see The Sorrow and the Pity down the road? She objects that the credits would be in Swedish and therefore incomprehensible, but he remains obdurate, so off they go, even though The Sorrow and the Pity is, at over four hours, twice the length of the film they would have seen. 2 The film they would have seen is Ingmar Bergman’s Face to Face , with Liv Ullmann as the mentally-disturbed psychiatrist – you see the poster behind them as they argue. The whole scene is a gesture. Your attention is being drawn to an influence even while that influence is being denied: for, though I don’t believe Bergman has seen too much Allen, Allen has watched all the Bergman there is, several times over. As an example: you don’t often hear Allen’s early comedy Bananas being referred to as Bergman-influenced: but not only does its deranged Fidel Castro-figure proclaim that from now on the official language of the revolutionised country will be Swedish, but in the first reel there’s a straight Bergman parody. -

100 Anni Di Ingmar Bergman

100 ANNI DI INGMAR BERGMAN settembre - dicembre 2018 UFFICIO CINEMA Collana a cura dell’Ufficio Cinema del Comune di Reggio Emilia piazza Casotti 1/c - 42121 Reggio Emilia telefono 0522/456632 - 456763 fax 0522/585241 cura rassegna e organizzazione 100 ANNI DI INGMAR BERGMAN Sandra Campanini cura catalogo Angela Cervi impaginazione Angela Cervi amministrazione Cinzia Biagi servizi tecnici Ero Incerti servizi diversi Giorgio Guerri Cinema Rosebud settembre - dicembre 2018 PROGRAMMA SOMMARIO lunedì 17 settembre 7 CIÒ CHE RISPONDE INGMAR BERGMAN, QUANDO RISPONDE • IL POSTO DELLE FRAGOLE (1957) 91’ 9 INTRODUZIONE di Jacques Mandelbaum lunedì 24 settembre 15 LO SCHIAFFO DI “LUCI D’INVERNO” • MONICA E IL DESIDERIO (1952) 92’ di Aldo Garzia mercoledì 7 novembre 21 I COLLEGHI REGISTI, LA CURIOSITÀ PER I GIOVANI di Aldo Garzia • IL SETTIMO SIGILLO (1957) 96’ LE SCHEDE lunedì 26 novembre 31 IL POSTO DELLE FRAGOLE • SUSSURRI E GRIDA (1972) 91’ 41 MONICA E IL DESIDERIO lunedì 10 dicembre 51 IL SETTIMO SIGILLO • SCENE DA UN MATRIMONIO (1975) 168’ 61 SUSSURRI E GRIDA 71 SCENE DA UN MATRIMONIO mercoledì 19 dicembre 79 FANNY E ALEXANDER • FANNY E ALEXANDER (1982) 188’ 93 BIOGRAFIA 101 FILMOGRAFIA 4 5 “”CIÒ CHE RISPONDE INGMAR BERGMAN, QUANDO RISPONDE” (Il regista)... È un illusionista. Se guardiamo l’elemento fondamentale dell’arte cinematografica constatiamo che questa si compone di piccole immagini rettangolari ognuna delle quali è separata dalle altre da una grossa riga nera. Guardando più da vicino si scopre che questi minuscoli rettangoli, i quali a prima vista sembrano contenere lo stesso motivo, differiscono l’uno dall’altro per una modificazione quasi impercettibile di tale motivo. -

Woody Allen Loves Ingmar Bergman Peter Cochran

1 Woody Allen loves Ingmar Bergman Peter Cochran Somewhere near the start of Annie Hall , Diane Keaton turns up late for a date at the cinema with Woody Allen, and they miss the credits. He says that, being anal, he has to see a film right through from the very start to the final finish, so it’s no go for that movie – why don’t they go see The Sorrow and the Pity down the road? She objects that the credits would be in Swedish and therefore incomprehensible, but he remains obdurate, so off they go, even though The Sorrow and the Pity is, at over four hours, twice the length of the film they would have seen. The film they would have seen is Ingmar Bergman’s Face to Face , with Liv Ullmann as the mentally-disturbed psychiatrist – you see the poster behind them as they argue. The whole scene is a gesture. Your attention is being drawn to an influence even while that influence is being denied: for, though I don’t believe Bergman has seen too much Allen, Allen has watched all the Bergman there is, several times over. As an example: you don’t often hear Allen’s early comedy Bananas being referred to as Bergman-influenced: but not only does its deranged Fidel Castro-figure proclaim that from now on the official language of the revolutionised country will be Swedish, but in the first reel there’s a straight Bergman parody. We all remember the dream in Wild Strawberries where Isak Borg sees his own funeral on a deserted Swedish street: in Bananas, Allen dreams 2 his own crucifixion on a deserted Manhattan Street. -

Marketing the University of Calgary to Frosh: a Motivational Typology of Student-College Choice

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 404 930 HE 029 935 AUTHOR Barnetson, Robert James TITLE Marketing the University of Calgary to Frosh: A Motivational Typology of Student-College Choice. PUB DATE 97 NOTE 100p.; M.A. Thesis, University of Calgary. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Masters Theses (042) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Attitude Measures; *College Bound Students; *College Choice; College Freshmen; Decision Making; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; High Schools; High School Students; Questionnaires; *Student Attitudes; Student Motivation; *Student Recruitment; Surveys IDENTIFIERS *University of Calgary (Canada) ABSTRACT This thesis proposes a segmentation of the University of Calgary's (Canada) freshman class based on benefits sought from attendance and provides descriptions of each benefit segment that includes the impact of institutional characteristics. A motivational typology for university participation is presented and the marketing implications of this segmentation on recruiting prospective students are explored. A four-cluster segmentation emerged from analysis, illustrating the predominance of fiscal motives in motivating freshmen from the Baby-Bust and Echo-Bust cohorts to attend a university. A questionnaire was developed which covered biographical information, reasons for attendance, and institutional characteristics. Questionnaire responses were analyzed from 77 freshmen students (out of a sample of 300) at the University of Calgary who had graduated from high school in June 1996. The following motives were most frequently cited as reasons for deciding to attend college: achievement of a higher standard of living, expansion of career opportunities, and career goal requirements. Other motives included the desire to: obtain a degree, have fun, become self-sufficient, learn new things, increase understanding, and meet new people. -

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

·ļ¯Æ ¼Æ›¼ Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

è‹±æ ¼çŽ›Â·ä¼¯æ ¼æ›¼ 电影 串行 (大全) Ingmar Bergman's https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ingmar-bergman%27s-cinema-59725709/actors Cinema Herr Sleeman kommer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/herr-sleeman-kommer-28153912/actors FÃ¥rö trilogy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-trilogy-12043076/actors Crisis https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/crisis-1066211/actors The Blessed Ones https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-blessed-ones-1079728/actors Port of Call https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/port-of-call-1108471/actors Thirst https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/thirst-1188701/actors FÃ¥rö Document 1979 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-document-1979-18239069/actors Stimulantia https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/stimulantia-222633/actors The Venetian https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-venetian-2276647/actors The Image Makers https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-image-makers-2755257/actors Don Juan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/don-juan-3035815/actors FÃ¥rö Document https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-document-64768851/actors metaphysical trilogy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/metaphysical-trilogy-98970250/actors 女人的秘密 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E5%A5%B3%E4%BA%BA%E7%9A%84%E7%A7%98%E5%AF%86-1078811/actors é¢ å” https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E9%9D%A2%E5%AD%94-1078890/actors 愛的一課 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E6%84%9B%E7%9A%84%E4%B8%80%E8%AA%B2-1091180/actors -

Divine Comedy

Divine Comedy Author(s): Alighieri, Dante (1265-1321) Publisher: CCEL Description: Dante©s Divine Comedy is the masterpiece of the Italian lan- guage. Written between 1308 and 1321, the three-part epic poem is well-known as a literary classic. The poem features Dante as the main character (though it is fiction), and de- scribes his journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Pur- gatorio) and Heaven (Paradiso). He meets many angels, demons, and other human travelers on this trip, and his guides are the Latin poet Virgil and Beatrice, a woman he loved. Under the surface, though, Divine Comedy is an al- legory. Dante uses his journey to represent the soul©s movement toward God, and the poem has many other reli- gious themes, mostly gathered from the medieval theology of Thomas Aquinas. The poem is extremely intricate, and mathematical and scientific patterns can be found throughout. Dante also makes many cultural references and allusions, Greek and Roman myth provide many of the characters and history, and the story even has political themes. Divine Comedy is a work that explores the afterlife from a medieval perspective. It is a fascinating read that will entrance all who take the journey with Dante. Abby Zwart CCEL Staff Writer i Contents Divine Comedy 1 Title Page 1 Credits 2 Inferno 3 Canto I 4 Canto II 8 Canto III 12 Canto IV 16 Canto V 20 Canto VI 24 Canto VII 28 Canto VIII 32 Canto IX 36 Canto X 40 Canto XI 44 Canto XII 48 Canto XIII 52 Canto XIV 56 Canto XV 60 Canto XVI 64 Canto XVII 68 Canto XVIII 72 Canto XIX 76 Canto XX 80 Canto -

Migration - Nomadism - Life in Motion 36/2017

36 www.maska.psc.uj.edu.pl 4/2017 ISSN: 1898-5947 magazyn antropologiczno-społeczno-kulturowy magazyn 001101 :) ;p K B 36 migration - nomadism - life in motion 36/2017 Migration – Nomadism – Life in motion Cracow 2017 „Maska” vol. 36 Chief editor: Cracow 2017 Katarzyna Kleczkowska ISSN: 1898-5947 Editorial staff: Print: 100 copies Marta Błaszkowska Free copy Tomasz P. Bocheński Agnieszka Kiejziewicz “Maska” is a peer reviewed academic journal. Anna Kuchta According to requirements of MNiSW (Ministry Agnieszka Lakner of Science and Higher Education) a full annual Joanna Malita-Król list of article reviewers is available on the Maciej Kuster following webpage: www.maska.psc.uj.edu.pl/ Gabriela Matusiak maska/listy-recenzentow Wawrzyniec Miścicki All texts and illustrations (unless stated Elżbieta Musialik otherwise) are published in open access mode, Filip Nowak according to Copyright Law for non-commercial Piotr Wajda purposes (under Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 Magdalena Wąsowicz obligations). Kama Wodyńska Adam Woźniak Full texts and summaries of published works are Agnieszka Wójcik available on-line in the international database “The Central European Journal of Social Sciences Proof-readers: and Humanities” (cejsh.icm.edu.pl). Agnieszka Kiejziewicz Magdalena Stonawska Editorial office: ul. Grodzka 52 Composition: II piętro, s. 102 Izabela Pisarek 31-044 Kraków Karol Ossowski [email protected] www.maska.psc.uj.edu.pl Cover: Paweł Kalina This project was financed by: Print: AT Wydawnictwo tel. 504 799 323 www.atwydawnictwo.pl Table of contents Introduction 5 Leszek Sosnowski 7 Objects and ideas. Japan and Europe in the nineteenth century Adam Lovasz 21 Immobility and Impersonality: Phenomenology of the Comatose Body Weronika Kostecka 33 Once Upon a Time There Was a War: The Use of Fairy-tale Conventions in Contemporary Polish Literature for Children about Refugees Anna Kuchta 51 The Journey of Memory. -

In the Hands of Strangers: the Myth of Choice and Self- Determination for Chronic Pain Patients in Ontario

IN THE HANDS OF STRANGERS: THE MYTH OF CHOICE AND SELF- DETERMINATION FOR CHRONIC PAIN PATIENTS IN ONTARIO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN SOCIOLOGY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO NOVEMBER 2017 © GUADALUPE CONSUELO DYSON, 2017 i Abstract This study aimed to better understand and explain the lived experience of chronic pain patients within Ontario primary health care settings, their perceptions of self-determination, and the impact on their capacity to self-manage their condition and health-related quality of life. Through in-depth interviews with 23 chronic pain (CP) patients, this research establishes an emergent theme of alienation as a key sensitizing characteristic of the experience of the research participants. Self-Determination Theory suggests the management of pain is most effective when patients have a sense of agency and some measure of influence in their own health care. This view is consistent with the current provincial government policy of promoting Patient Centred Care (PCC). The results of this study suggest that CP respondents experience feelings of alienation in the management of their condition. This experience is evidence of a lack of self-determination created by the inability of the health care professionals to effectively put into practice PCC. ii Dedications To my son, Frederick and my sister, Mariana iii Acknowledgements A number of people contributed to the completion of this doctoral dissertation. I would like to express my deeply felt gratitude to all of them. I am extremely grateful to Dr. -

Name Group ########## Arab Countries

Name Group ########## Arab Countries ########## Arab Countries 2M Maroc ARB Arab Countries 4G Aflam ARB Arab Countries 4G Cima ARB Arab Countries 4G Cinema ARB Arab Countries 4G Classic ARB Arab Countries 4G Drama ARB Arab Countries 4G Film ARB Arab Countries 7Besha Cima ARB Arab Countries ABN TV ARB Arab Countries AL Anbar ARB Arab Countries AL Arabia AL Hadath ARB Arab Countries AL Arabia News ARB Arab Countries AL Fajer 1 ARB Arab Countries AL Fajer 2 ARB Arab Countries AL Magharibia ARB Arab Countries AL Majd ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Educational ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Hadith ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Kids ARB Arab Countries AL Majd Quran ARB Arab Countries AL Mayadeen ARB Arab Countries AL Nabaa ARB Arab Countries AL Nahar ARB Arab Countries AL Rafidain ARB Arab Countries AL Salam Palestine ARB Arab Countries ANB ARB Arab Countries ANN ARB Arab Countries ART Aflam 1 ARB Arab Countries ART Aflam 2 ARB Arab Countries ART Cinema ARB Arab Countries ART Hikayat 2 ARB Arab Countries ART Hekayat 1 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Drama HD ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Nat Geo ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 1 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 2 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 3 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi Sports 4 ARB Arab Countries Abu Dhabi TV ARB Arab Countries Aden TV ARB Arab Countries Afaq TV ARB Arab Countries Afrah TV ARB Arab Countries Aghanina ARB Arab Countries Aghapy TV ARB Arab Countries Ajman TV ARB Arab Countries Ajyal ARB Arab Countries Al Aan TV ARB Arab Countries Al Adjwaa ARB Arab Countries Al Ahd ARB Arab -

Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie José

UNIVERSIDADE PRESBITERIANA MACKENZIE JOSÉ LUIZ DE CAMPOS CASTEJÓN BRANCO A ANGÚSTIA NA OBRA DE INGMAR BERGMAN: SARABANDA EM SER E TEMPO DE MARTIN HEIDEGGER São Paulo 2009 Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. JOSÉ LUIZ DE CAMPOS CASTEJÓN BRANCO A ANGÚSTIA NA OBRA DE INGMAR BERGMAN: SARABANDA EM SER E TEMPO DE MARTIN HEIDEGGER Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura da Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Regina Célia Faria Amaro Giora São Paulo 2009 B816a Branco, José Luiz de Campos Castejón. A angústia na obra de Ingmar Bergman: Sarabanda em Ser e Tempo de Martin Heidegger / José Luiz de Campos Castejón – 2009. 173 f. : il. ; 30 cm. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura) – Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, São Paulo, 2009. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Regina Célia Faria Amaro Giora Bibliografia: f. 151 - 158. 1. Angústia. 2. Condição humana. 3. Estruturas ontológicas. 4. Fenomenologia. 5. Manifestações ônticas. I. Título. CDD 791.4309 JOSÉ LUIZ DE CAMPOS CASTEJÓN BRANCO A ANGÚSTIA NA OBRA DE INGMAR BERGMAN: SARABANDA EM SER E TEMPO DE MARTIN HEIDEGGER Dissertação apresentada à Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Educação, Arte e História da Cultura. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Regina Célia Faria Amaro Giora Aprovado em BANCA EXAMINADORA Profª. Drª. Regina Célia Faria Amaro Giora - Orientadora Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie Prof. Dr. Orlando Bruno Linhares Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie Profª.