TRACING OPERATIC PERFORMANCES in the LONG NINETEENTH CENTURY Practices, Performers, Peripheries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

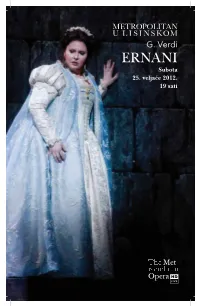

ERNANI Web.Pdf

Foto: Metropolitan opera G. Verdi ERNANI Subota, 25. veljae 2012., 19 sati THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Giuseppe Verdi ERNANI Opera u etiri ina Libreto: Francesco Maria Piave prema drami Hernani Victora Hugoa SUBOTA, 25. VELJAČE 2012. POČETAK U 19 SATI. Praizvedba: Teatro La Fenice u Veneciji, 9. ožujka 1844. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 18. studenoga 1871. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 28. siječnja 1903. Premijera ove izvedbe: 18. studenoga 1983. ERNANI Marcello Giordani JAGO Jeremy Galyon DON CARLO, BUDUĆI CARLO V. Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana Dmitrij Hvorostovsky ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo DON RUY GOMEZ DE SILVA DIRIGENT Marco Armiliato Ferruccio Furlanetto REDATELJ I SCENOGRAF ELVIRA Angela Meade Pier Luigi Samaritani GIOVANNA Mary Ann McCormick KOSTIMOGRAF Peter J. Hall DON RICCARDO OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE Gil Wechsler Adam Laurence Herskowitz SCENSKA POSTAVA Peter McClintock Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Radnja se događa u Španjolskoj 1519. godine. Stanka nakon prvoga i drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 22 sata i 50 minuta. Tekst: talijanski. Titlovi: engleski. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: PRVI IN - IL BANDITO (“Mercè, diletti amici… Come rugiada al ODMETNIK cespite… Oh tu che l’ alma adora”). Otac Don Carlosa, u operi Don Carla, Druga slika dogaa se u Elvirinim odajama u budueg Carla V., Filip Lijepi, dao je Silvinu dvorcu. Užasnuta moguim brakom smaknuti vojvodu od Segovije, oduzevši sa Silvom, Elvira eka voljenog Ernanija da mu imovinu i prognavši obitelj. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Pauline Viardot-Garcia Europäische

Beatrix Borchard PAULINE VIARDOT-GARCIA EUROPÄISCHE KOMPONISTINNEN Herausgegeben von Annette Kreutziger-Herr und Melanie Unseld Band 9 Beatrix Borchard PAULINE VIARDOT-GARCIA Fülle des Lebens 2016 BÖHLAU VERLAG KÖLN WEIMAR WIEN Die Reihe »Europäische Komponistinnen« wird ermöglicht durch die Mariann Steegmann Foundation Weiterführende Quellen und Materialien finden Sie auf der Buchdetailseite http://www.boehlau-verlag.com/978-3-412-50143-3.html unter Downloads Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://portal.dnb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung: Pauline Viardot, Porträt von Ary Scheffer, 1840 (© Stéphane Piera / Musée de la Vie Romantique / Roger-Viollet) © 2016 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Cie, Köln Weimar Wien Ursulaplatz 1, D-50668 Köln, www.boehlau.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig. Korrektorat: Katharina Krones, Wien Satz: Peter Kniesche Mediendesign, Weeze Druck und Bindung: Strauss, Mörlenbach Gedruckt auf chlor- und säurefreiem Papier Printed in the EU ISBN 978-3-412-50143-3 Inhalt Vorwort der Herausgeberinnen ............................................................. 9 Vorbemerkung ....................................................................................... 11 Freiheit und Bindung – Pauline Viardot-Garcia .......................... -

La Couleur Du Temps – the Colour of Time Salzburg Whitsun Festival 29 May – 1 June 2020

SALZBURGER FESTSPIELE PFINGSTEN Künstlerische Leitung: Cecilia Bartoli La couleur du temps – The Colour of Time Pauline Viardot-Garcia (1821 – 1910) Photo: Uli Weber - Decca Salzburg Whitsun Festival 29 May – 1 June 2020 (SF, 30 December 2019) The life of Pauline Viardot-Garcia – singer, musical ambassador of Europe, outstanding pianist and composer – is the focus of the 2020 programme of the Salzburg Whitsun Festival. “The uncanny instinct Cecilia Bartoli has for the themes of our times is proven once again by her programme for the 2020 Salzburg Whitsun Festival, which focuses on Pauline Viardot. Orlando Figes has just written a bestseller about this woman. Using Viardot as an example, he describes the importance of art within the idea of Europe,” says Festival President Helga Rabl-Stadler. 1 SALZBURGER FESTSPIELE PFINGSTEN Künstlerische Leitung: Cecilia Bartoli Pauline Viardot not only made a name for herself as a singer, composer and pianist, but her happy marriage with the French theatre manager, author and art critic Louis Viardot furthered her career and enabled her to act as a great patron of the arts. Thus, she made unique efforts to save the autograph of Mozart’s Don Giovanni for posterity. Don Giovanni was among the manuscripts Constanze Mozart had sold to Johann Anton André in Offenbach in 1799. After his death in 1842, his daughter inherited the autograph and offered it to libraries in Vienna, Berlin and London – without success. In 1855 her cousin, the pianist Ernst Pauer, took out an advertisement in the London-based journal Musical World. Thereupon, Pauline Viardot-García bought the manuscript for 180 pounds. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Maria Di Rohan

GAETANO DONIZETTI MARIA DI ROHAN Melodramma tragico in tre atti Prima rappresentazione: Vienna, Teatro di Porta Carinzia, 5 VI 1843 Donizetti aveva già abbozzato l'opera (inizialmente intitolata Un duello sotto Richelieu) a grandi linee a Parigi, nel dicembre 1842, mentre portava a termine Don Pasquale; da una lettera del musicista si desume che la composizione fu ultimata il 13 febbraio dell'anno successivo. Donizetti attraversava un periodo di intensa attività compositiva, forse consapevole dell'inesorabile aggravarsi delle proprie condizioni di salute; la "prima" ebbe luogo sotto la sua direzione e registrò un convincente successo (furono apprezzate soprattutto l'ouverture ed il terzetto finale). L'opera convinse essenzialmente per le sue qualità drammatiche, eloquentemente rilevate dagli interpreti principali: Eugenia Tadolini (Maria), Carlo Guasco (Riccardo) e Giorgio Ronconi (Enrico); quest'ultimo venne apprezzato in modo particolare, soprattutto nel finale. Per il Theatre Italien Donizetti preparò una nuova versione, arricchita di due nuove arie, nella quale la parte di Armando fu portata dal registro di tenore a quello di contralto (il ruolo fu poi interpretato en travesti da Marietta Brambilla). Con la rappresentazione di Parma (primo maggio 1844) Maria di Rohan approdò in Italia dove, da allora, è stata oggetto soltanto di sporadica considerazione. Nel nostro secolo è stata riallestita a Bergamo nel 1957 ed alla Scala nel 1969, oltre all'estero (a Londra e a New York, dove è apparsa in forma di concerto). Maria di Rohan segna forse il punto più alto di maturazione nell'itinerario poetico di Donizetti; con quest'opera il musicista approfondì la propria visione drammatica, a scapito di quella puramente lirica e belcantistica, facendo delle arie di sortita un vero e proprio studio di carattere e privilegiando i duetti ed i pezzi d'assieme in luogo degli 276 episodi solistici (ricordiamo, tra i momenti di maggior rilievo, l'aria di Maria "Cupa, fatal mestizia" ed il duetto con Chevreuse "So per prova il tuo bel core"). -

The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-5-2016 The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda Juanita Ulloa Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Ulloa, Juanita, "The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda" (2016). Dissertations. Paper 339. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2016 JUANITA ULLOA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School THE SONGS OF MEXICAN NATIONALIST, ANTONIO GOMEZANDA A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Juanita M. Ulloa College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music Department of Voice May, 2016 This Dissertation by: Juanita M. Ulloa Entitled: The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Visual and Performing Arts, School of Music, Department of Voice Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ____________________________________________________ Dr. Melissa Malde, D.M.A., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Paul Elwood, Ph.D., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Carissa Reddick, Ph.D., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Professor Brian Luedloff, M.F.A., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Weis, Ph.D., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense . Accepted by the Graduate School ____________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. -

Svenskt Portråttgalleri

SVENSKT PORTRÅTTGALLERI XXI. TONKONSTNARER OCH SCENISKA ARTISTER STOCKHOLM HASSIS W. TUr,I,BERGS KORLAG STOCKHOLM HASSE W. TTJUBERGS BORTRYCKERI lS97 TONKONSTNÅRER OCH SCENISKA ARTISTER MED KIOGRAFISKA UPPGIFTER ADOLF LINDGREN ocn NILS PERSONNE . FORORD. Alla portrått i denna afdelning, innefattande ton- såttare, vokala och instrumentala virtuoser samt dra- matiska konstnårer, åro ordnade i alfabetisk f'oljd. En del sceniska artister hor nåmligen både till den lyriska och dramatiska kategorien och redan dårfor har det varit nodvåndigt att sammanfora alla i en f'oljd, hvilket ock torde underlåtta uppslagningen. De biograftska uppgifterna ha naturligen mast inskrånkas till de ound- gångligaste data jånite kort forteckning på en del roller eller kompositioner Någon uttommande fullståndighet kan en samling af detta slag icke gora anspråk på. Skulle man taga med alla Sveriges musik- och skådespelsidkare, så skulle listan springa upp till många tusental, och arbetet dårigenom komma att stålla sig allt for dyrt. I sjalfua urvalet kunna ju alltid olika meningar gora sig gal- lande. De, som till åfuentyrs tycka, att vi varit for liberala och upptagit åfven obetydligare namn, erinras dårom, att galleriet icke vill galla som någon estetisk vårdesåttning, utan år till for allmånhetens skull och upptager sådana konstutofvare , som man antager hafva gjort sig offentligen så pass kånda, att allmånheten kan vilja se deras konterfej. De, som åter mojligen skulle onska flera namn, erinras forst om nyss nåinnda nodvåndighet af begrånsning och vidare dårom, att åtskilliga af dem, som blifvit anmodade att insdnda portrått, dels ingenting svarat, dels nttalat sig af- bbjande, samt att for en del, sårskildt aldre och aflidna artister, det varit omojligt att ofverkomma vare sig portrått eller biografi. -

INHALT DES ZWEITEN BANDES Nr

INHALT DES ZWEITEN BANDES Nr. 121-200 r. ~ ~~ t t Nr, Texte..r~h.n.g .;,ummcnzanl Komponist Advent 121. Gelobet sei Israels Gott . 4 . johann Crüger 122. Hod!gelobet seist du jesu Christe Gom Sohn 2 . Ernst Pepping 123. Vom Olberge zeucht daher ·..... 4 . Joachim a Burck 124. Aus hartem Weh die Menschheit klagt 2-4. Ernst Pepping 125. Gott heilger Schöpfer aller Stern 3 Guillaume Dufay 126. Gelobet sei der König groß . 4 Michael Praetorius 127. Und unser lieben Frauen ... 3 . Ernst Pepping 128. Maria durch ein Dornwald ging 6 Heinrich Kaminski Weibnachren 129. In dulci iubilo ...... 8 Leonhard Schröter 130. Hört zu und seid getrost nun . 4 Leonhard Schröter 131. Christum wir sollen loben schon 4 . Ernst Pepping 132. Christe redemptor omnium . 4 Giov. P. da Palestrina Christe Erlöser aller Welt . 133. Hört zu ihr lieben Leute . 5 Michael Praetorius IH. Universi populi . 4 Michael Praetorius Fröhlich seid all Christenleut 135. In Bethlchem ein Kindelein . 4 Michael Praetorius 136. Ein Kind geborn zu Bethlehem 2~. Michael Practorius Puer natus in Bethlehem . 137. Uns ist ein Kind geboren . 6 . johann Stobäus 138. Aus des Vaters Herz ist gboren 4 . Kurt H essenberg ll9. Zu Bethlehem geboren . 3-4 . Ernst Pcpping Neujahr 140. jesu du zartes Kindelein . 5 Melchior Franck 141. Nun wollen wir das alte Jahr mit Lob und Dank vollenden 5 johann Staden Epiphanias 142. Nun liebe See! nun ist es Zeit . 6 johann Eccard 143. Gott Vater uns sein Sohn fürstellt 3 Adam Gumpelzhaimer Passion 1«. 0 du armer Judas . 6 . Arnold von Bruck 145. Da jesus an dem Kreuze stund . -

THE JVEDIS. ART SONG Presented to the Graduate Council of the North

110,2 THE JVEDIS. ART SONG THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial ifillment of the requirements For the Degree of MAST ER OF MUSIC by 223569 Alfred R. Skoog, B. Mus. Borger, Texas August, 1953 223569 PREFACE The aim of this thesis is to present a survey of Swedish vocal music, a subject upon which nothing in English exists and very little in Swedish. Because of this lack of material the writer, who has spent a year (195152) of research in music in Sweden, through the generosity of Mrs. Alice M. Roberts, the Texas Wesleyan Academy, and the Texas Swedish Cultural Foundation, has been forced to rely for much of his information on oral communication from numerous critics, composers, and per- formers in and around Stockholm. This accounts for the paucity of bibliographical citations. Chief among the authorities consulted was Gsta Percy, Redaktionssekreterare (secretary to the editor), of Sohlmans Jusiklexikon, who gave unstintedly, not only of his vast knowledge, but of his patience and enthusiasm. Without his kindly interest this work would have been impossible, iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page . 1.F. .:.A . !. !. ! .! . .! ! PREFACE.! . ! .0 01 ! OF LIST ITLISTRATITONS. - - - . a- . a . V FORH4ORD . .* . .- . * .* . * * * * * * * . vii Chapter I. EARLYSEDIS0H SONG. I The Uppsala School II. NINETEENTH CENTURY NATIONALISTS . 23 The Influence of Mid-Nineteenth Century German Romanticism (Mendelssohn, Schumann, Liszt and Wagner) The French Influence III. LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY ND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY COMPOSERS . 52 Minor Vocal Composers of the Late Nine- teenth Century and Early Twentieth Century IV. THE MODERN SCHOOL OF S7E)ISl COMPOSERS. -

Komponisten 1618Caccini

© Albert Gier (UNIV. BAMBERG), NOVEMBER 2003 KOMPONISTEN 1618CACCINI LORENZO BIANCONI, Giulio Caccini e il manierismo musicale, Chigiana 25 (1968), S. 21-38 1633PERI HOWARD MAYER BROWN, Music – How Opera Began: An Introduction to Jacopo Peri´s Euridice (1600), in: The Late Italian Renaissance 1525-1630, hrsg. von ERIC COCHRANE, London: Macmillan 1970, S. 401-443 WILLIAM V. PORTER, Peri and Corsi´s Dafne: Some New Discoveries and Observations, Journal of the American Musicological Society 17 (1975), S. 170-196 OBIZZI P. PETROBELLI, L’ “Ermonia“ di Pio Enea degli Obizzi ed i primi spettacoli d´opera veneziani, Quaderni della Rassegna musicale 3 (1966), S. 125-141 1643MONTEVERDI ANNA AMALIE ABERT, Claudio Monteverdi und das musikalische Drama, Lippstadt: Kistner & Siegel & Co. 1954 Claudio Monteverdi und die Folgen. Bericht über das Internationale Symposium Detmold 1993, hrsg. von SILKE LEOPOLD und JOACHIM STEINHEUER, Kassel – Basel – London – New York – Prag: Bärenreiter 1998, 497 S. Der Band gliedert sich in zwei Teile: Quellen der Monteverdi-Rezeption in Europa (8 Beiträge) sowie Monteverdi und seine Zeitgenossen (15 Beiträge); hier sollen nur jene Studien vorgestellt werden, in denen Libretto und Oper eine Rolle spielen: H. SEIFERT, Monteverdi und die Habsburger (S. 77-91) [faßt alle bekannten Fakten zusammen und fragt abschließend (S. 91) nach möglichen Einflüssen Monteverdis auf das Wiener Opernschaffen]. – A. SZWEYKOWSKA, Monteverdi in Polen (S. 93-104) [um 1600 wirken in Polen zahlreiche italienische Musiker, vor allem in der königlichen Hofkapelle; Monteverdi lernte den künftigen König Wladyslaw IV. 1625 in Venedig kennen. Marco Scacchi, der Leiter der Kapelle, deren Mitglieder auch drammi per musica komponierten (vgl.