Status of Common Leopard Panthera Pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Kunjo VDC of Mustang District, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panthera Pardus, Leopard

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T15954A5329380 Panthera pardus, Leopard Assessment by: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser- Wursten, C. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser-Wursten, C. 2008. Panthera pardus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15954A5329380. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15954A5329380.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Carnivora Felidae Taxon Name: Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) Synonym(s): • Felis pardus Linnaeus, 1758 Regional Assessments: • Mediterranean Infra-specific Taxa Assessed: • Panthera pardus ssp. -

Subspecies of Sri Lankan Mammals As Units of Biodiversity Conservation, with Special Reference to the Primates

Ceylon Journal of Science (Bio. Sci.) 42(2): 1-27, 2013 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/cjsbs.v42i2.6606 LEAD ARTICLE Subspecies of Sri Lankan Mammals as Units of Biodiversity Conservation, with Special Reference to the Primates Wolfgang P. J. Dittus1, 2 1National Institute of Fundamental Studies, Kandy 2000, Sri Lanka. 2Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Washington, DC 20013, USA. ABSTRACT Subspecies embody the evolution of different phenotypes as adaptations to local environmental differences in keeping with the concept of the Evolutionary Significant Unit (ESU). Sri Lankan mammals, being mostly of Indian-Indochinese origins, were honed, in part, by the events following the separation of Sri Lanka from Gondwana in the late Miocene. The emerging new Sri Lankan environment provided a varied topographic, climatic and biotic stage and impetus for new mammalian adaptations. This history is manifest nowhere as clearly as in the diversity of non-endemic and endemic genera, species and subspecies of Sri Lankan mammals that offer a cross-sectional time-slice (window) of evolution in progress: 3 of 53 genera (6%), and 22 of 91 species (24%) are endemic, but incorporating subspecies, the majority 69 of 108 (64%) Sri Lankan land-living indigenous mammal taxa are diversified as endemics. (Numerical details may change with taxonomic updates, but the pattern is clear). These unique forms distinguish Sri Lankan mammals from their continental relatives, and contribute to the otherwise strong biogeographic differences within the biodiversity hotspot shared with the Western Ghats. Regardless of the eventual fates of individual subspecies or ESU’s they are repositories of phenotypic and genetic diversity and crucibles for the evolution of new endemic species and genera. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Leopard (Panthera Pardus) Status, Distribution, and the Research Efforts Across Its Range

Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range Andrew P. Jacobson1,2,3, Peter Gerngross4, Joseph R. Lemeris Jr.3, Rebecca F. Schoonover3, Corey Anco5, Christine Breitenmoser- Wu¨rsten6, Sarah M. Durant1,7, Mohammad S. Farhadinia8,9, Philipp Henschel10, Jan F. Kamler10, Alice Laguardia11, Susana Rostro-Garcı´a9, Andrew B. Stein6,12 and Luke Dollar3,13,14 1 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, United Kingdom 2 Department of Geography, University College London, London, United Kingdom 3 Big Cats Initiative, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., United States 4 BIOGEOMAPS, Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Biological Sciences, Fordham University, Bronx, NY, United States 6 IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, c/o KORA, Bern, Switzerland 7 Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx Zoo, Bronx, NY, United States 8 Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), Tehran, Iran 9 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, The Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Tubney, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom 10 Panthera, New York, NY, United States 11 The Wildlife Institute, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 12 Landmark College, Putney, VT, United States 13 Department of Biology, Pfeiffer University, Misenheimer, NC, United States 14 Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States ABSTRACT The leopard’s (Panthera pardus) broad geographic range, remarkable adaptability, and secretive nature have contributed to a misconception that this species might not be severely threatened across its range. We find that not only are several subspecies and regional populations critically endangered but also the overall range loss is greater than the average for terrestrial large carnivores. 31 December 2015 Submitted To assess the leopard’s status, we compile 6,000 records at 2,500 locations Accepted 5 April 2016 Published 4May2016 from over 1,300 sources on its historic (post 1750) and current distribution. -

Poisoning of Endangered Ara- Bian Leopard in Saudi Arabia and Its

short communication M. ZAFAR-UL ISLAM1*, AHMED BOUG1, ABDULLAH AS-SHEHRI1 & MUKHLID AL JAID1 depleted key prey populations like the Nubian ibex Capra nubiana, Hyrax Procavia capensis, Poisoning of endangered Ara- and Cape hare Lepus capensis (Al Johany 2007). As a consequence, the leopard has be- bian leopard in Saudi Arabia come increasingly dependent upon domestic stock for its subsistence, in turn leading to and its conservation efforts retaliation by those herders losing animals. Carcasses are poisoned and traps set to kill Many killings of leopards can be attributed to livestock protection. When catching the predator whenever it is encountered (Ju- goats, sheep, young camels or other domestic animals, leopards interfere with hu- das et al. 2006). Although legally protected, man activities and are seen as straight competitors. With the decrease of natural the current law enforcement is ineffective (Al prey species, they have to more and more shift their diet to livestock, which increas- Johany 2007, Judas et al. 2006). Finally, there es their unpopularity. In most cases, they are also considered as a threat for human. are reports of the sale of furs and rarely live As a result, leopard is hunted across its range, with different methods (trapping, poi- animals sold in the market. For example one soning, shooting). Poisoning using anticoagulant rat killer was common in the eight- cat was sold for $4,800 in the Al Khawbah ies, which was stopped in 1985 unlike trapping. A total of only five known incidences market in 1997 (Judas et al. 2006). Leopard of poisoning of Arabian leopards Panthera pardus nimr have been recorded in Saudi fat is valued by some locals for its perceived Arabia between 1965 and 2014. -

Critically Endangered Arabian Leopards Panthera Pardus Nimr Persist in the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, Oman

Oryx Vol 40 No 3 July 2006 Critically Endangered Arabian leopards Panthera pardus nimr persist in the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, Oman James Andrew Spalton, Hadi Musalam al Hikmani, David Willis and Ali Salim Bait Said Abstract Between 1997 and 2000 a survey of the unrecorded in Jabal Samhan. Although people are Arabian subspecies of leopard Panthera pardus nimr mostly absent from the Reserve there is some conflict was conducted in the little known Jabal Samhan Nature between leopards and shepherds who live outside the Reserve in southern Oman. Using camera-traps 251 Reserve. The numbers and activities of frankincense photographic records were obtained of 17 individual harvesters in the Reserve need to be managed to leopards; nine females, five males, two adults of safeguard the leopard and its habitat. The main unknown sex and one cub. Leopards were usually challenge for the future is to find ways whereby local solitary and trail use and movements suggested large communities can benefit from the presence of the ranges characterized by spatial sharing but little Reserve and from the leopards that the Reserve seeks temporal overlap. More active by day than night in to safeguard. undisturbed areas, overall the leopards exhibited two peaks in activity, morning and evening. The survey also Keywords Arabia, Arabian leopard, camera-traps, provided records of leopard prey species and first Dhofar, Jabal Samhan, leopards, Oman, Panthera pardus records of nine Red List mammal species previously nimr. Introduction thought to have come from Jabal Samhan in 1947, and a further specimen was obtained elsewhere in Dhofar in The Arabian subspecies of leopard Panthera pardus nimr 1947–1948 (Harrison, 1968). -

The Endangerment and Conservation of Cheetahs (Acinonyx Jubatus), Leopards (Panthera Pardus), Lions (Panthera Leo), and Tigers (Panthera Tigris) in Africa and Asia

The endangerment and conservation of cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), leopards (Panthera pardus), lions (Panthera leo), and tigers (Panthera tigris) in Africa and Asia Britney Johnston * B.S. Candidate, Department of Biological Sciences, California State University Stanislaus, 1 University Circle, Turlock, CA 95382 Received 17 April, 2018; accepted 15 May 2018 Abstract Increasing habitat depletion, habitat degradation, and overhunting in Africa and Asia have resulted in the designation of the four largest species of felid (cheetah, leopard, lion, tiger) as vulnerable or endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Scientists interested in understanding and potentially slowing the disappearance of these species need access to causal factors, the past and current range of each species, the life history, and importance of conservation. This article presents one such resource with all of this information compiled in a place that Is easy for people to get to. The primary target of this article is educators but will be useful to anyone interested in these species, their current state, and their future peril. Keywords: cheetah, leopard, lion, tiger, endangered species, conservation, Old World, big cats, habitat Introduction world with some species programs. These steps are used to analyze whether or not a species is in danger and are Conservationism is a common term heard in many then used to halt the decline and reverse it. The first is settings in the modern world, implying that an effort to population decline; this is the obvious decline in a conserve species needs to be made and enforced. population that incites a need for a change to be made. -

Travel + Leisure Southeast Asia

One final check that all 2,500 Night Safari animals are safe for the evening. OPPOSITE A stealthy Sri Lankan leopard. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE 72 MARCH 2014 TRAVELANDLEISUREASIA.COM Animal-uneducated melanie lee trains as a zookeeper at Singapore’s Night Safari, and discovers the quirky charm of its nocturnal residents. photographed by darren soh , A PHOENIX MUSCULAR BALL PYTHON FROM AFRICA, writhes around in my hands. “Being a keeper is all about mutual respect and trust between animals and humans,” says Natalie Chan, a supervisor at Singapore’s Night Safari. “The animals may not understand what you say, but they feel your energy and, as much as possible, you try to make that I am not up to carrying either of these animals for the daily them feel comfortable.” roving session at the Night Safari entrance. “You just help visitors My response? Yelping: “Help!” The take photos with these animals instead,” assistant communications python senses my unease and manager Natt Haniff says. attempts to slither out of my hands. In the real zookeeper world, I would probably have been fired. Chan takes Phoenix and he Luckily, I’m only doing a three-day stint behind the scenes at the immediately calms down and hangs 20-year-old Night Safari. The world’s first nocturnal zoo and one of off her arms in complete stillness. “He Singapore’s most popular tourist destinations with 1.1 million visitors senses your nervousness,” she tells annually, the Night Safari is my go-to spot to bring friends from out of me. -

Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species

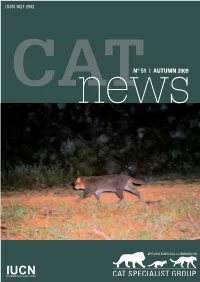

ISSN 1027-2992 CATnewsN° 51 | AUTUMN 2009 01 IUCNThe WorldCATnews Conservation 51Union Autumn 2009 news from around the world KRISTIN NOWELL1 Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species The IUCN Red List is the most authoritative lists participating in the assessment pro- global index to biodiversity status and is the cess. Distribution maps were updated and flagship product of the IUCN Species Survi- for the first time are being included on the val Commission and its supporting partners. Red List website (www.iucnredlist.org). Tex- As part of a recent multi-year effort to re- tual species accounts were also completely assess all mammalian species, the family re-written. A number of subspecies have Felidae was comprehensively re-evaluated been included, although a comprehensive in 2007-2008. A workshop was held at the evaluation was not possible (Nowell et al Oxford Felid Biology and Conservation Con- 2007). The 2008 Red List was launched at The fishing cat is one of the two species ference (Nowell et al. 2007), and follow-up IUCN’s World Conservation Congress in Bar- that had to be uplisted to Endangered by email with others led to over 70 specia- celona, Spain, and since then small changes (Photo A. Sliwa). Table 1. Felid species on the 2009 Red List. CATEGORY Common name Scientific name Criteria CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus C2a(i) ENDANGERED (EN) Andean cat Leopardus jacobita C2a(i) Tiger Panthera tigris A2bcd, A4bcd, C1, C2a(i) Snow leopard Panthera uncia C1 Borneo bay cat Pardofelis badia C1 Flat-headed -

WME Vol.3 Issue 1 E Final

Volume 3 • Issue 1 • June 2008 • ISSN 1990-8237 YEMENI LEOPARD RECOVERY PROGRAMME David B. Stanton fundraising items such as cards and posters, produce content for the YLRP website (under construction), Sana’a International School, P.O. Box 2002, Sana’a, Republic of Yemen. [email protected] and make presentations about conservation issues to Yemeni schoolchildren in other schools. Keywords: Arabian Leopard, Conservation, Yemen, nimr, Wada’a In just a few months the YLRP has achieved some The Arabian Leopard (Panthera pardus nimr) is arguably the rarest large cat on the planet. While this notable accomplishments. We have brought the issue dubious distinction, based on a wild population of some 30 individuals, is generally given to the Amur of leopard conservation to the attention of thousands Leopard (P.p. orientalis), there are close to 500 Amur Leopards held in zoos around the world. Wild Arabian of Yemenis through articles in local newspapers and Leopards might, by the most optimistic estimates, outnumber their far-Eastern cousins by as much as six magazines and in presentations to various audiences. to one, but with only 50 or so Arabian Leopards in captivity P.p. nimr is still at least twice as scarce as We have initiated an institution-building process at orientalis. That the Arabian subspecies survives at all is no small miracle on a peninsula where charismatic Sana’a Zoo which should pave the way for improved wildlife continues to disappear at an alarming rate. The Arabian Leopard’s tenuous persistence in the facilities for their captive leopards and better utilization wild is attributable to the resourcefulness of the animal, the ruggedness of the terrain that it inhabits, and of the zoo’s ability to educate a proportion of its 1.4 pioneering conservation efforts across the peninsula, most notably in Oman and Sharjah, UAE. -

Conservation Strategy for the Arabian Peninsula

Strategy for the Conservation of the Leopard in the Arabian Peninsula Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................7 1. Intorduction ................................................................................................9 2. Status and Distribution .............................................................................10 3. Problem Analysis .....................................................................................12 4. Range-wide Conservation Strategy ..........................................................13 5. Implementation of the Arabina Leopard Conservation Strategy .............18 6. References ................................................................................................22 7. Acknowledgements ..................................................................................22 Appendix I: List of Workshop Participants .................................................23 Appendix II: List of Range State Agencies ..................................................24 Editors: Urs & Christine Breitenmoser, David Mallon & Jane-Ashley Edmonds Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Amal Al Hosani Translation: Nashat Hamidan Cover photo: Arabian Leopard in Oman Photo: Andrew Spalton. Foreword by His Highness the Ruler of Sharjah Al nimr al-arabi, the Arabian leopard, is a uniquely small, genetically distinctive, desert-adapted form of the leopard that is endemic to the Arabian Peninsula. It once occurred around the moun- tainous rim -

Activity Report 2015/2016 02

activity 2015/2016report 01 Activity Report 2015/2016 02 The IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group The Cat Specialist Group is responsible for the global assessment of the conservation status of all 37 wild living cat species. We coordinate and support the activities of currently 203 leading scientists, nature conservation officers and wildlife managers in currently 57 countries. The main tasks include: - to maintain the network of cat experts and partners; - to continuously assess the status and conservation needs of the 37 cat species; - to support governments with strategic conservation planning and implementation of conservation action; - to develop capacity in felid conservation; - to provide services to members and partners and outreach; - to assure the financial resources for the Cat Specialist Group. For the activity reports we present some of our achievements against these main tasks. Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten and Urs Breitenmoser Co-chairs IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Cover photo: Fishing cat (Photo A. Sliwa) IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group activity report 2015/16: contents The Network IUCN Species Survival Commission Leaders’ meeting in Abu Dhabi, UAE .....................................................4 Species Assessment and Conservation Activities Multi-species database workshop in Nairobi, Kenya.......................................................................................5 Global Mammal Assessment - update .............................................................................................................6