Panthera Pardus Kotiya) Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panthera Pardus, Leopard

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T15954A5329380 Panthera pardus, Leopard Assessment by: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser- Wursten, C. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser-Wursten, C. 2008. Panthera pardus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15954A5329380. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15954A5329380.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Carnivora Felidae Taxon Name: Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) Synonym(s): • Felis pardus Linnaeus, 1758 Regional Assessments: • Mediterranean Infra-specific Taxa Assessed: • Panthera pardus ssp. -

Status of Common Leopard Panthera Pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Kunjo VDC of Mustang District, Nepal

Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. Status of Common Leopard Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Kunjo VDC of Mustang District, Nepal Submitted by Yadav Ghimirey M.Sc thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Environmental Management Evaluation Committee: Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah Advisor (Member) ………………………… Co-ordinator/AP (Member) ………………………… (Member) Yadav Ghimirey Previous Degree: Bachelor of Science Sikkim Government College Gangtok, Sikkim India School of Environmental Management and Sustainable Development Shantinagar, Kathmandu Nepal October 2006 1 Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms ………………………………………………...................i List of Tables .................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures .................................................................................................................. iii List of Plates ……............................................................................................................. iv Abstract ..............................................................................................................................v Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... vi 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….....1 -

Subspecies of Sri Lankan Mammals As Units of Biodiversity Conservation, with Special Reference to the Primates

Ceylon Journal of Science (Bio. Sci.) 42(2): 1-27, 2013 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/cjsbs.v42i2.6606 LEAD ARTICLE Subspecies of Sri Lankan Mammals as Units of Biodiversity Conservation, with Special Reference to the Primates Wolfgang P. J. Dittus1, 2 1National Institute of Fundamental Studies, Kandy 2000, Sri Lanka. 2Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Washington, DC 20013, USA. ABSTRACT Subspecies embody the evolution of different phenotypes as adaptations to local environmental differences in keeping with the concept of the Evolutionary Significant Unit (ESU). Sri Lankan mammals, being mostly of Indian-Indochinese origins, were honed, in part, by the events following the separation of Sri Lanka from Gondwana in the late Miocene. The emerging new Sri Lankan environment provided a varied topographic, climatic and biotic stage and impetus for new mammalian adaptations. This history is manifest nowhere as clearly as in the diversity of non-endemic and endemic genera, species and subspecies of Sri Lankan mammals that offer a cross-sectional time-slice (window) of evolution in progress: 3 of 53 genera (6%), and 22 of 91 species (24%) are endemic, but incorporating subspecies, the majority 69 of 108 (64%) Sri Lankan land-living indigenous mammal taxa are diversified as endemics. (Numerical details may change with taxonomic updates, but the pattern is clear). These unique forms distinguish Sri Lankan mammals from their continental relatives, and contribute to the otherwise strong biogeographic differences within the biodiversity hotspot shared with the Western Ghats. Regardless of the eventual fates of individual subspecies or ESU’s they are repositories of phenotypic and genetic diversity and crucibles for the evolution of new endemic species and genera. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Leopard (Panthera Pardus) Status, Distribution, and the Research Efforts Across Its Range

Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range Andrew P. Jacobson1,2,3, Peter Gerngross4, Joseph R. Lemeris Jr.3, Rebecca F. Schoonover3, Corey Anco5, Christine Breitenmoser- Wu¨rsten6, Sarah M. Durant1,7, Mohammad S. Farhadinia8,9, Philipp Henschel10, Jan F. Kamler10, Alice Laguardia11, Susana Rostro-Garcı´a9, Andrew B. Stein6,12 and Luke Dollar3,13,14 1 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, United Kingdom 2 Department of Geography, University College London, London, United Kingdom 3 Big Cats Initiative, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., United States 4 BIOGEOMAPS, Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Biological Sciences, Fordham University, Bronx, NY, United States 6 IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, c/o KORA, Bern, Switzerland 7 Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx Zoo, Bronx, NY, United States 8 Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), Tehran, Iran 9 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, The Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Tubney, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom 10 Panthera, New York, NY, United States 11 The Wildlife Institute, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 12 Landmark College, Putney, VT, United States 13 Department of Biology, Pfeiffer University, Misenheimer, NC, United States 14 Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States ABSTRACT The leopard’s (Panthera pardus) broad geographic range, remarkable adaptability, and secretive nature have contributed to a misconception that this species might not be severely threatened across its range. We find that not only are several subspecies and regional populations critically endangered but also the overall range loss is greater than the average for terrestrial large carnivores. 31 December 2015 Submitted To assess the leopard’s status, we compile 6,000 records at 2,500 locations Accepted 5 April 2016 Published 4May2016 from over 1,300 sources on its historic (post 1750) and current distribution. -

The Endangerment and Conservation of Cheetahs (Acinonyx Jubatus), Leopards (Panthera Pardus), Lions (Panthera Leo), and Tigers (Panthera Tigris) in Africa and Asia

The endangerment and conservation of cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), leopards (Panthera pardus), lions (Panthera leo), and tigers (Panthera tigris) in Africa and Asia Britney Johnston * B.S. Candidate, Department of Biological Sciences, California State University Stanislaus, 1 University Circle, Turlock, CA 95382 Received 17 April, 2018; accepted 15 May 2018 Abstract Increasing habitat depletion, habitat degradation, and overhunting in Africa and Asia have resulted in the designation of the four largest species of felid (cheetah, leopard, lion, tiger) as vulnerable or endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Scientists interested in understanding and potentially slowing the disappearance of these species need access to causal factors, the past and current range of each species, the life history, and importance of conservation. This article presents one such resource with all of this information compiled in a place that Is easy for people to get to. The primary target of this article is educators but will be useful to anyone interested in these species, their current state, and their future peril. Keywords: cheetah, leopard, lion, tiger, endangered species, conservation, Old World, big cats, habitat Introduction world with some species programs. These steps are used to analyze whether or not a species is in danger and are Conservationism is a common term heard in many then used to halt the decline and reverse it. The first is settings in the modern world, implying that an effort to population decline; this is the obvious decline in a conserve species needs to be made and enforced. population that incites a need for a change to be made. -

Travel + Leisure Southeast Asia

One final check that all 2,500 Night Safari animals are safe for the evening. OPPOSITE A stealthy Sri Lankan leopard. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE 72 MARCH 2014 TRAVELANDLEISUREASIA.COM Animal-uneducated melanie lee trains as a zookeeper at Singapore’s Night Safari, and discovers the quirky charm of its nocturnal residents. photographed by darren soh , A PHOENIX MUSCULAR BALL PYTHON FROM AFRICA, writhes around in my hands. “Being a keeper is all about mutual respect and trust between animals and humans,” says Natalie Chan, a supervisor at Singapore’s Night Safari. “The animals may not understand what you say, but they feel your energy and, as much as possible, you try to make that I am not up to carrying either of these animals for the daily them feel comfortable.” roving session at the Night Safari entrance. “You just help visitors My response? Yelping: “Help!” The take photos with these animals instead,” assistant communications python senses my unease and manager Natt Haniff says. attempts to slither out of my hands. In the real zookeeper world, I would probably have been fired. Chan takes Phoenix and he Luckily, I’m only doing a three-day stint behind the scenes at the immediately calms down and hangs 20-year-old Night Safari. The world’s first nocturnal zoo and one of off her arms in complete stillness. “He Singapore’s most popular tourist destinations with 1.1 million visitors senses your nervousness,” she tells annually, the Night Safari is my go-to spot to bring friends from out of me. -

Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species

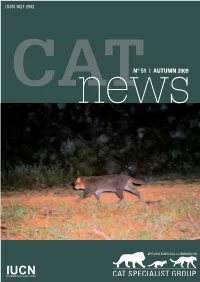

ISSN 1027-2992 CATnewsN° 51 | AUTUMN 2009 01 IUCNThe WorldCATnews Conservation 51Union Autumn 2009 news from around the world KRISTIN NOWELL1 Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species The IUCN Red List is the most authoritative lists participating in the assessment pro- global index to biodiversity status and is the cess. Distribution maps were updated and flagship product of the IUCN Species Survi- for the first time are being included on the val Commission and its supporting partners. Red List website (www.iucnredlist.org). Tex- As part of a recent multi-year effort to re- tual species accounts were also completely assess all mammalian species, the family re-written. A number of subspecies have Felidae was comprehensively re-evaluated been included, although a comprehensive in 2007-2008. A workshop was held at the evaluation was not possible (Nowell et al Oxford Felid Biology and Conservation Con- 2007). The 2008 Red List was launched at The fishing cat is one of the two species ference (Nowell et al. 2007), and follow-up IUCN’s World Conservation Congress in Bar- that had to be uplisted to Endangered by email with others led to over 70 specia- celona, Spain, and since then small changes (Photo A. Sliwa). Table 1. Felid species on the 2009 Red List. CATEGORY Common name Scientific name Criteria CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus C2a(i) ENDANGERED (EN) Andean cat Leopardus jacobita C2a(i) Tiger Panthera tigris A2bcd, A4bcd, C1, C2a(i) Snow leopard Panthera uncia C1 Borneo bay cat Pardofelis badia C1 Flat-headed -

Wildlife in India

Wildlife India 2 Hemis Rajaji Corbett Dudhwa Chitwan National Park Sariska Bharatpur Desert Manas Kaziranga Ranthambore Jawai Dam Panna Bandhavgarh Kanha Kisli Sasan Gir Satpura Pench Sundarbans Tadoba Nagarhole Bandipur Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary Periyar Horton Plains National Park Wildlife India Yala National Park 3 RANTHAMBORE NATIONAL PARK Location Located in Sawai Madhopur District of Southern Eastern Rajasthan Distance and driving Nearest airport Jaipur 4 hours' drive approx time Nearest Railway station Sawai Madhopur Railway station 30 minutes driving time approx. Area Covered 392 km² Animals Tigers, Leopards, Striped Hyenas, Sambar deer, Chital, Nilgai, Common or Hanuman langurs, Macaques, Jackals, Jungle cats, Caracals, Sloth bears, Black bucks, Rufoustailed Hare, Indian Wild Boar, Chinkara, Common Palm Civets or Toddy cat, Coomon Yellow Bats, Desert Cats, Fivestriped Palm Squirels, Indian False Vampires, Indian Flying Foxes, Indian Foxes, Indian Gerbilles, Indian Mole Rats, Indian Porcupines, Longeared Hedgehogs, Ratels, Small Indian Mongoose, Small Indian Civets and Common mongoose. Best time to visit 1st October to 31st March Closing time 1st July to 30th September Safari information Safaris available by shared canter (16 or 20 seater open bus) by shared / exclusive Jeep (seating capacity of 5 persons) Safari timings 1 Oct to 31 Oct 6:30 to 10:00 am / 2:30 to 6:00 pm 1 Nov to 31 Jan 7:00 to 10:30 am / 2:00 to 5:30 pm 1 Feb to 31 Mar 6:30 to 10:00 am / 2:30 to 6:00 pm 1 Apr to 15 May 6:00 to 9:30 am / 3:00 to 6:30 pm 1 Apr to 30 Jun 6:00 to 9:30 am / 3:30 to 7:00 pm Booking information Booked - 90 days in advance & necessary Passport details required to book game rides requirements Zones 1-5 Core Zones 6-10 Buer Zones Hotels available Aman-i-Khas approx 5 kms (25 minutes) The Oberoi Vanyavilas approx. -

EAZA TAG Reports 2018

THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIA TAG Reports 2018 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Callitrichid 36 Glossary 2 Larger New World Monkey 38 Terrestrial Invertebrate 3 Old World Monkey 40 Fish And Aquatic Invertebrate 4 Gibbon 42 Amphibian 7 Great Ape 43 Reptile 10 Small Mammal 47 Ratite 14 Canid And Hyaenid 49 Penguin 15 Bear 51 Ciconiiformes And Phoenicopteriformes 17 Small Carnivore 53 Waterfowl And Pelecaniformes 19 Felid 55 Falconiformes And Strigiformes 21 Marine Mammal 56 Galliformes 23 Elephant 58 Gruiformes 24 Equid 60 Charadriiformes 24 Rhinoceros 62 Pigeon And Dove 25 Tapir And Suiform 64 Parrot 26 Cattle And Camelid 66 Toucan And Turaco 28 Deer 68 Hornbill 29 Antelope And Giraffid 68 Passeriformes 30 Caprinae 70 Monotreme And Marsupial 33 Long-Term Management Plans 72 Prosimian 35 Cover image: The Canid and Hyaenid Taxon Advisory Group were the first to complete the new style Regional Collection Plan. Painted dog (Lycaon pictus) pups at Yorkshire Wildlife Park © Yorkshire Wildlife Park TAG Reports 2018 INTRODUCTION This Annual Report clearly showcases the range was wonderfully hosted by Budapest Zoo (Hungary). and diversity of activities that EAZA’s 39 Taxon Advisory The meeting provided a unique opportunity to discuss Groups (TAG) were involved in over the course of 2018. topics including integrated conservation, the One The implementation of the revolutionary new Plan Approach, cooperation with zoos and aquariums EAZA Population Management structure started very in other regions and animal welfare and population successfully with the first new style Regional Collection management. Many TAGs also held their mid-year Plans (RCP) and the first new style EAZA Ex situ meeting in Budapest and used the opportunity to Programmes (EEP) approved by the EEP Committee. -

Wide Distribution of an Apex Carnivore and Umbrella Species, the Sri Lankan Leopard (Panthera Pardus Kotiya)

Biodivers Conserv DOI 10.1007/s10531-017-1431-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Forest cover and level of protection influence the island- wide distribution of an apex carnivore and umbrella species, the Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya) 1 1 2,3 Andrew M. Kittle • Anjali C. Watson • Samuel A. Cushman • David. W. Macdonald3 Received: 15 January 2017 / Revised: 8 June 2017 / Accepted: 2 September 2017 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2017 Abstract Apex predators fulfil potentially vital ecological roles. Typically wide-ranging and charismatic, they can also be useful surrogates for biodiversity preservation, making their targeted conservation imperative. The Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya), an endangered, endemic sub-species, is the island’s apex predator. Of potential keystone importance, this carnivore also fulfills ‘‘umbrella’’ and ‘‘flagship’’ criterion and is of high ecological and existence value. Apex predator conservation requires identifying factors underlying distribution, so we used multi-scale maximum entropy modelling with sam- pling bias correction to investigate a broad suite of relevant ecological, climatic and anthropogenic factors in order to identify potentially suitable leopard habitat. Presence locations were determined from 15 years of surveys, observations and verified reports. The best bias correction procedure and scale were uncertain, so we employed a novel method of using information from all models across analyses to determine top models and identify influential variables. Leopard presence was most strongly linked to the landscape pro- portion encompassed by Protected Areas strictly limiting human presence, with more porous Protected Areas less influential. All three forest composition and configuration metrics investigated (area weighted mean patch size, patch density and forest connectivity) were influential, with increased patch size and higher connectivity predicting better habitat suitability for leopards. -

25 Jan 2020 26 Jan 2020

Lunar New Year 2019 Animal Enrichment Schedule 25 Jan 2020 Please note that all activities are weather permitting and subject to change Time Species Location Fishing Cat Trail 9.00pm Southern Three Banded Armadillo Fishing Cat Trail Leopard Trail Northern Luzon Cloud Rat Leopard Trail 8.30pm Small-toothed Palm Civet Leopard Trail East Lodge Trail 9.30pm Sloth Bear East Lodge Trail On Tram Route Malayan Tiger On Tram Route 9.30pm Sloth Bear On Tram Route 26 Jan 2020 Please note that all activities are weather permitting and subject to change Time Species Location Fishing Cat Trail 9.00pm Binturong Fishing Cat Trail Leopard Trail 8.30pm Malayan Porcupine Leopard Trail 9.00pm Northern Luzon Cloud Rat Leopard Trail East Lodge Trail 9.00pm Serval East Lodge Trail On Tram Route 9.30pm Malayan Tiger On Tram Route Page 1 of 6 Lunar New Year 2019 Animal Enrichment Schedule 27 Jan 2020 Please note that all activities are weather permitting and subject to change Time Species Location Fishing Cat Trail 9.00pm Common Palm Civet Fishing Cat Trail Leopard Trail Masked Palm Civet Leopard Trail 8.30pm Binturong Leopard Trail 9.00pm Northern Luzon Cloud Rat Leopard Trail East Lodge Trail 9.00pm Spotted Hyena East Lodge Trail 28 Jan 2020 Please note that all activities are weather permitting and subject to change Time Species Location Fishing Cat Trail 9.00pm Fishing Cat Fishing Cat Trail Leopard Trail 8.30pm Sri Lankan Leopard Leopard Trail 9.00pm Giant Flying Squirrel Leopard Trail 29 Jan 2020 Please note that all activities are weather permitting and