Leopard (Panthera Pardus) Status, Distribution, and the Research Efforts Across Its Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panthera Pardus, Leopard

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T15954A5329380 Panthera pardus, Leopard Assessment by: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser- Wursten, C. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser-Wursten, C. 2008. Panthera pardus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15954A5329380. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15954A5329380.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Carnivora Felidae Taxon Name: Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) Synonym(s): • Felis pardus Linnaeus, 1758 Regional Assessments: • Mediterranean Infra-specific Taxa Assessed: • Panthera pardus ssp. -

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard Under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes Ivan Csiszar, Tatiana Loboda, Dale Miquelle, Nancy Sherman, Hank Shugart, Tim Stephens. The Study Region Primorsky Krai has a large systems of reserves and protected areas. Tigers are wide ranging animals and are not necessarily contained by these reserves. Tigers areSiberian in a state Tigers of prec areipitous now restricted decline worldwide. Yellow is tothe Primorsky range in 1900;Krai in red the is Russian the current or potential habitat, todayFar East Our (with study a possible focuses few on the in Amur Tiger (PantheraNorthern tigris altaica China).), the world’s largest “big cat”. The Species of Panthera Amur Leopard (P. pardus orientalis) Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) One of the greatest threats to tigers is loss of habitat and lack of adequate prey. Tiger numbers can increase rapidly if there is sufficient land, prey, water, and sheltered areas to give birth and raise young. The home range territory Status: needed Critically depends endangered on the Status: Critically endangered (less than (less than 50 in the wild) 400 in the wild) Females: 62 – 132density lbs; of prey. Females: Avg. about 350 lbs., to 500 lbs.; Males: 82 – 198 lbs Males: Avg. about 500 lbs., to 800 lbs. Diet: Roe deer (Capreolus Key prey: Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), pygargus), Sika Deer, Wild Boar, Wild Boar (Sus scrofa), Sika Deer Hares, other small mammals (Cervus nippon), small mammals The Prey of Panthera Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Called Elk or Wapiti in the US. The Prey of Panthera Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) The Prey of Panthera Roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) The Prey of Panthera Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Amur Tigers also feed occasionally on Moose (Alces alces). -

Opportunity for Thailand's Forgotten Tigers: Assessment of the Indochinese Tiger Panthera Tigris Corbetti and Its Prey with Camera-Trap Surveys

Opportunity for Thailand's forgotten tigers: assessment of the Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti and its prey with camera-trap surveys E RIC A SH, Ż ANETA K ASZTA,ADISORN N OOCHDUMRONG,TIM R EDFORD P RAWATSART C HANTEAP,CHRISTOPHER H ALLAM,BOONCHERD J AROENSUK S OMSUAN R AKSAT,KANCHIT S RINOPPAWAN and D AVID W. MACDONALD Abstract Dramatic population declines threaten the En- Keywords Bos gaurus, distribution, Dong Phayayen-Khao dangered Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti with ex- Yai Forest Complex, Indochinese tiger, Panthera tigris tinction. Thailand now plays a critical role in its conservation, corbetti, prey abundance, Rusa unicolor, Sus scrofa as there are few known breeding populations in other Supplementary material for this article is available at range countries. Thailand’s Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai For- doi.org/./S est Complex is recognized as an important tiger recovery site, but it remains poorly studied. Here, we present results from the first camera-trap study focused on tigers and im- plemented across all protected areas in this landscape. Our Introduction goal was to assess tiger and prey populations across the five protected areas of this forest complex, reviewing discernible he tiger Panthera tigris has suffered catastrophic de- patterns in rates of detection. We conducted camera-trap Tclines in its population (%) and habitat (%) over surveys opportunistically during –. We recorded the past century (Nowell & Jackson, ; Goodrich et al., , detections of tigers in , camera-trap nights. ; Wolf & Ripple, ). Evidence suggests only source Among these were at least adults and six cubs/juveniles sites (i.e. sites with breeding populations that have the po- from four breeding females. -

2012 WCS Report Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in The

Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in the Russian Far East Final Report to The Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA) from the WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY (WCS) March 2012 Project Location: Southwest Primorskii Krai, Russian Far East Grant Period: July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Project Coordinators: Dale Miquelle, PhD Alexey Kostyria, PhD E: [email protected] E: [email protected] SUMMARY From March to June 2011 we recorded 156 leopard photographs, bringing our grand total of leopard camera trap photographs (2002-present) to 756. In 2011 we recorded 17 different leopards on our study area, the most ever in nine years of monitoring. While most of these likely represent transients, it is still a positive sign that the population is reproducing and at least maintaining itself. Additionally, camera trap monitoring in an adjacent unit just south of our study area reported 12 leopards, bringing the total minimum number of leopards to 29. Collectively, these results suggest that the total number of leopards in the Russian Far East is presently larger than the 30 individuals usually reported. We also recorded 7 tigers on the study area, including 3 cubs. The number of adult tigers on the study area has remained fairly steady over all nine years of the monitoring program. INTRODUCTION The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is the northern-most of the nine extant subspecies (Miththapala et al., 1996; Uphyrkina et al., 2001), with a very small global distribution in the southernmost corner of the Russian Far East (two counties in Primorye Province), and in neighboring Jilin Province, China. -

Status of Common Leopard Panthera Pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Kunjo VDC of Mustang District, Nepal

Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. Status of Common Leopard Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Kunjo VDC of Mustang District, Nepal Submitted by Yadav Ghimirey M.Sc thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Environmental Management Evaluation Committee: Prof. Karan Bahadur Shah Advisor (Member) ………………………… Co-ordinator/AP (Member) ………………………… (Member) Yadav Ghimirey Previous Degree: Bachelor of Science Sikkim Government College Gangtok, Sikkim India School of Environmental Management and Sustainable Development Shantinagar, Kathmandu Nepal October 2006 1 Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Acronyms ………………………………………………...................i List of Tables .................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures .................................................................................................................. iii List of Plates ……............................................................................................................. iv Abstract ..............................................................................................................................v Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... vi 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….....1 -

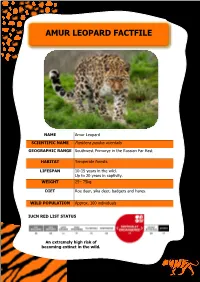

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Panthera Pardus) and Its Extinct Eurasian Populations Johanna L

Paijmans et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018) 18:156 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1268-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) and its extinct Eurasian populations Johanna L. A. Paijmans1* , Axel Barlow1, Daniel W. Förster2, Kirstin Henneberger1, Matthias Meyer3, Birgit Nickel3, Doris Nagel4, Rasmus Worsøe Havmøller5, Gennady F. Baryshnikov6, Ulrich Joger7, Wilfried Rosendahl8 and Michael Hofreiter1 Abstract Background: Resolving the historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) is a complex issue, because patterns inferred from fossils and from molecular data lack congruence. Fossil evidence supports an African origin, and suggests that leopards were already present in Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene. Analysis of DNA sequences however, suggests a more recent, Middle Pleistocene shared ancestry of Asian and African leopards. These contrasting patterns led researchers to propose a two-stage hypothesis of leopard dispersal out of Africa: an initial Early Pleistocene colonisation of Asia and a subsequent replacement by a second colonisation wave during the Middle Pleistocene. The status of Late Pleistocene European leopards within this scenario is unclear: were these populations remnants of the first dispersal, or do the last surviving European leopards share more recent ancestry with their African counterparts? Results: In this study, we generate and analyse mitogenome sequences from historical samples that span the entire modern leopard distribution, as well as from Late Pleistocene remains. We find a deep bifurcation between African and Eurasian mitochondrial lineages (~ 710 Ka), with the European ancient samples as sister to all Asian lineages (~ 483 Ka). The modern and historical mainland Asian lineages share a relatively recent common ancestor (~ 122 Ka), and we find one Javan sample nested within these. -

Status of the African Wild Dog in the Bénoué Complex, North Cameroon

Croes et al. African wild dogs in Cameroon Copyright © 2012 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478-2677 Distribution Update Status of the African wild dog in the Bénoué Complex, North Cameroon 1* 2,3 1 1 Barbara Croes , Gregory Rasmussen , Ralph Buij and Hans de Iongh 1 Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML), University of Leiden, The Netherlands 2 Painted dog Conservation (PDC), Hwange National Park, Box 72, Dete, Zimbabwe 3 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK * Correspondence author Keywords: Lycaon pictus, North Cameroon, monitoring surveys, hunting concessions Abstract The status of the African wild dog Lycaon pictus in the West and Central African region is largely unknown. The vast areas of unspoiled Sudano-Guinean savanna and woodland habitat in the North Province of Cameroon provide a potential stronghold for this wide-ranging species. Nevertheless, the wild dog is facing numerous threats in this ar- ea, mainly caused by human encroachment and a lack of enforcement of laws and regulations in hunting conces- sions. Three years of surveys covering over 4,000km of spoor transects and more than 1,200 camera trap days, in addition to interviews with local stakeholders revealed that the African wild dog in North Cameroon can be consid- ered functionally extirpated. Presence of most other large carnivores is decreasing towards the edges of protected areas, while presence of leopard and spotted hyaena is negatively associated with the presence of villages. Lion numbers tend to be lower inside hunting concessions as compared to the national parks. -

The Role of Small Private Game Reserves in Leopard Panthera Pardus and Other Carnivore Conservation in South Africa

The role of small private game reserves in leopard Panthera pardus and other carnivore conservation in South Africa Tara J. Pirie Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Reading for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences November 2016 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors Professor Mark Fellowes and Dr Becky Thomas, without whom this thesis would not have been possible. I am sincerely grateful for their continued belief in the research and my ability and have appreciated all their guidance and support. I especially would like to thank Mark for accepting this project. I would like to acknowledge Will & Carol Fox, Alan, Lynsey & Ronnie Watson who invited me to join Ingwe Leopard Research and then aided and encouraged me to utilize the data for the PhD thesis. I would like to thank Andrew Harland for all his help and support for the research and bringing it to the attention of the University. I am very grateful to the directors of the Protecting African Wildlife Conservation Trust (PAWct) and On Track Safaris for their financial support and to the landowners and participants in the research for their acceptance of the research and assistance. I would also like to thank all the Ingwe Camera Club members; without their generosity this research would not have been possible to conduct and all the Ingwe Leopard Research volunteers and staff of Thaba Tholo Wilderness Reserve who helped to collect data and sort through countless images. To Becky Freeman, Joy Berry-Baker -

Subspecies of Sri Lankan Mammals As Units of Biodiversity Conservation, with Special Reference to the Primates

Ceylon Journal of Science (Bio. Sci.) 42(2): 1-27, 2013 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/cjsbs.v42i2.6606 LEAD ARTICLE Subspecies of Sri Lankan Mammals as Units of Biodiversity Conservation, with Special Reference to the Primates Wolfgang P. J. Dittus1, 2 1National Institute of Fundamental Studies, Kandy 2000, Sri Lanka. 2Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Washington, DC 20013, USA. ABSTRACT Subspecies embody the evolution of different phenotypes as adaptations to local environmental differences in keeping with the concept of the Evolutionary Significant Unit (ESU). Sri Lankan mammals, being mostly of Indian-Indochinese origins, were honed, in part, by the events following the separation of Sri Lanka from Gondwana in the late Miocene. The emerging new Sri Lankan environment provided a varied topographic, climatic and biotic stage and impetus for new mammalian adaptations. This history is manifest nowhere as clearly as in the diversity of non-endemic and endemic genera, species and subspecies of Sri Lankan mammals that offer a cross-sectional time-slice (window) of evolution in progress: 3 of 53 genera (6%), and 22 of 91 species (24%) are endemic, but incorporating subspecies, the majority 69 of 108 (64%) Sri Lankan land-living indigenous mammal taxa are diversified as endemics. (Numerical details may change with taxonomic updates, but the pattern is clear). These unique forms distinguish Sri Lankan mammals from their continental relatives, and contribute to the otherwise strong biogeographic differences within the biodiversity hotspot shared with the Western Ghats. Regardless of the eventual fates of individual subspecies or ESU’s they are repositories of phenotypic and genetic diversity and crucibles for the evolution of new endemic species and genera. -

Carnivore Hotspots in Peninsular Malaysia and Their Landscape

1 Carnivore hotspots in Peninsular Malaysia and their 2 landscape attributes 3 Shyamala Ratnayeke1*¶, Frank T. van Manen2¶, Gopalasamy Reuben Clements1&, Noor Azleen 4 Mohd Kulaimi3&, Stuart P. Sharp4& 5 1Department of Biological Sciences, Sunway University, Malaysia 6 7 2U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, Bozeman, 8 MT 59715, USA 9 10 3Ex-Situ Conservation Division, Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Malaysia 11 12 4Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YQ, UK 13 14 15 16 *Corresponding author 17 Email: [email protected] 18 19 ¶SR and FTVM are joint senior authors 20 &These authors also contributed equally to this work 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Disclaimer: This draft manuscript is distributed solely for purposes of scientific peer review. Its content is 34 deliberative and pre-decisional, so it must not be disclosed or released by reviewers. Because the 35 manuscript has not yet been approved for publication by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), it does not 36 represent any official USGS finding or policy. 37 Abstract 38 Mammalian carnivores play a vital role in ecosystem functioning. However, they are prone to 39 extinction because of low population densities and growth rates, large area requirements, and 40 high levels of persecution or exploitation. In tropical biodiversity hotspots such as Peninsular 41 Malaysia, rapid conversion of natural habitats threatens the persistence of this vulnerable 42 group of animals. Here, we carried out the first comprehensive literature review on 31 43 carnivore species reported to occur in Peninsular Malaysia and updated their probable 44 distribution. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard