The Example of the Amur Leopard, Panthera Pardus Orientalis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard Under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes Ivan Csiszar, Tatiana Loboda, Dale Miquelle, Nancy Sherman, Hank Shugart, Tim Stephens. The Study Region Primorsky Krai has a large systems of reserves and protected areas. Tigers are wide ranging animals and are not necessarily contained by these reserves. Tigers areSiberian in a state Tigers of prec areipitous now restricted decline worldwide. Yellow is tothe Primorsky range in 1900;Krai in red the is Russian the current or potential habitat, todayFar East Our (with study a possible focuses few on the in Amur Tiger (PantheraNorthern tigris altaica China).), the world’s largest “big cat”. The Species of Panthera Amur Leopard (P. pardus orientalis) Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) One of the greatest threats to tigers is loss of habitat and lack of adequate prey. Tiger numbers can increase rapidly if there is sufficient land, prey, water, and sheltered areas to give birth and raise young. The home range territory Status: needed Critically depends endangered on the Status: Critically endangered (less than (less than 50 in the wild) 400 in the wild) Females: 62 – 132density lbs; of prey. Females: Avg. about 350 lbs., to 500 lbs.; Males: 82 – 198 lbs Males: Avg. about 500 lbs., to 800 lbs. Diet: Roe deer (Capreolus Key prey: Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), pygargus), Sika Deer, Wild Boar, Wild Boar (Sus scrofa), Sika Deer Hares, other small mammals (Cervus nippon), small mammals The Prey of Panthera Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Called Elk or Wapiti in the US. The Prey of Panthera Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) The Prey of Panthera Roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) The Prey of Panthera Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Amur Tigers also feed occasionally on Moose (Alces alces). -

2012 WCS Report Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in The

Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in the Russian Far East Final Report to The Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA) from the WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY (WCS) March 2012 Project Location: Southwest Primorskii Krai, Russian Far East Grant Period: July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Project Coordinators: Dale Miquelle, PhD Alexey Kostyria, PhD E: [email protected] E: [email protected] SUMMARY From March to June 2011 we recorded 156 leopard photographs, bringing our grand total of leopard camera trap photographs (2002-present) to 756. In 2011 we recorded 17 different leopards on our study area, the most ever in nine years of monitoring. While most of these likely represent transients, it is still a positive sign that the population is reproducing and at least maintaining itself. Additionally, camera trap monitoring in an adjacent unit just south of our study area reported 12 leopards, bringing the total minimum number of leopards to 29. Collectively, these results suggest that the total number of leopards in the Russian Far East is presently larger than the 30 individuals usually reported. We also recorded 7 tigers on the study area, including 3 cubs. The number of adult tigers on the study area has remained fairly steady over all nine years of the monitoring program. INTRODUCTION The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is the northern-most of the nine extant subspecies (Miththapala et al., 1996; Uphyrkina et al., 2001), with a very small global distribution in the southernmost corner of the Russian Far East (two counties in Primorye Province), and in neighboring Jilin Province, China. -

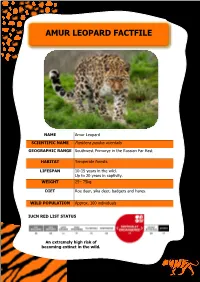

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Amur Tiger Conservation in Russia in 2017

Amur Tiger Conservation in Russia in 2017 Progress report by Phoenix Fund January 1 – June 30, 2017 SMART In February 2015, the simultaneous count of Amur tigers and Amur leopards showed that about 523-540 Amur tigers occur today in the Russian Far East (comparing to 430-500 individuals recorded during the previous count in 2005). Same upward tendency was registered with the global population of Amur leopards, which numbers grew from 30 to 60-70 species in a decade. Despite sustained conservation efforts over recent years and encouraging recent monitoring results, the big cats still remain at risk due to poaching, logging, forest fires, and prey depletion. Every year the wild populations of Amur tigers and Amur leopards officially lose up to ten individuals due to poaching, collisions with vehicles and other causes of death. According to official statistics and trusted sources, as many as 11 Amur tigers died from January through June 2017. The ongoing alarming mortality in these species requires powerful and innovative solutions that leverage and build on existing capacity if we are to be successful in halting the loss of invaluable endangered wildlife. In this regard, thanks to continuous support from the Kolmarden Fundraising Foundation Phoenix continued implementing its complex conservation programme with the following objectives: 1) to reduce poaching of Amur tigers and their prey species and improve protection of their habitat; 2) to improve law enforcement efforts within federal-level protected areas; 3) and to raise people’s awareness about the state of, and the threats to, the Amur tiger population and involve the public in nature conservation actions. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Tiger Conservation in the Russian Far East

Tiger Conservation in the Russian Far East Background The Russian Far East is home to the world’s only remaining population of wild Amur, or Siberian tigers, Panthera tigris altaica (Figures 1&2). Population surveys conducted in 2005 estimated this to be between 430 – 500 individuals (Miquelle et al. 2007), but since then numbers have declined even further, based both on data from the Amur Tiger Monitoring Program (a 13 year collaboration between WCS and Russian partners), and official government reports (Global Tiger Recovery Program 2010). An increase in poaching (Figure 3), combined with habitat loss, is the key driver of this downward trend. Furthermore, the appearance of disease-related deaths in tiger populations represents a new threat of unknown dimensions and one which is only just being acknowledged. WCS-Russia’s overall tiger program in the Russian Far East The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) has been active in the Russian Far East since 1992, working to conserve landscape species including Amur tigers, Far Eastern leopards and Blakiston’s fish owls, whose survival ultimately requires the conservation of the forest ecosystem as a whole. Our science-based approach, which relies on the findings of our research to design effective conservation interventions, emphasizes close collaboration with local stakeholders to improve wildlife and habitat management, both within and outside of protected areas, inclusion of local communities in resolving resource use issues, and the application of robust monitoring programs to understand the effectiveness of conservation interventions. Poaching of tigers and their prey appears to be the number one threat to tigers in the Russian Far East. -

Leopard (Panthera Pardus) Status, Distribution, and the Research Efforts Across Its Range

Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range Andrew P. Jacobson1,2,3, Peter Gerngross4, Joseph R. Lemeris Jr.3, Rebecca F. Schoonover3, Corey Anco5, Christine Breitenmoser- Wu¨rsten6, Sarah M. Durant1,7, Mohammad S. Farhadinia8,9, Philipp Henschel10, Jan F. Kamler10, Alice Laguardia11, Susana Rostro-Garcı´a9, Andrew B. Stein6,12 and Luke Dollar3,13,14 1 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, United Kingdom 2 Department of Geography, University College London, London, United Kingdom 3 Big Cats Initiative, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., United States 4 BIOGEOMAPS, Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Biological Sciences, Fordham University, Bronx, NY, United States 6 IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, c/o KORA, Bern, Switzerland 7 Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx Zoo, Bronx, NY, United States 8 Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), Tehran, Iran 9 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, The Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Tubney, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom 10 Panthera, New York, NY, United States 11 The Wildlife Institute, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 12 Landmark College, Putney, VT, United States 13 Department of Biology, Pfeiffer University, Misenheimer, NC, United States 14 Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States ABSTRACT The leopard’s (Panthera pardus) broad geographic range, remarkable adaptability, and secretive nature have contributed to a misconception that this species might not be severely threatened across its range. We find that not only are several subspecies and regional populations critically endangered but also the overall range loss is greater than the average for terrestrial large carnivores. 31 December 2015 Submitted To assess the leopard’s status, we compile 6,000 records at 2,500 locations Accepted 5 April 2016 Published 4May2016 from over 1,300 sources on its historic (post 1750) and current distribution. -

D Ocelot Club

STAFF: Mrs. Harry Cisin, Editor, An.agansett, N. Y. 1.1930 (516) 267 Robert Peraner, Associate Editor, 250 Willow Drive, Somerville, Mass. 02144 (617) 623 0444 Mrs. Daniel Treanor, Sec-Treas. 1454 Fleetwood Drive E., Mobile, Alabama 36605 (205) 478 8962 Dr. Michael Balbc, Art/Conservation, 21-01 46th Street Long Island City, N. Y. 11105 Wm. ~n~lei,~elidologi, P. 0. Drawer 1750, Buellton, Calif. 93427 (805) 688 3216 1 Lone- Island Ocelot Club. 1 ~mi&insett, N. Y. 11930 Volume 15, Number 2 March, 1971 March-April 1971 D OCELOT CLUB OMAR- Son of Trilby and Caesar, born 12/26/70 "earmarked" by Caesar? And now their offspring is at Studio Noir, 22 Isis Street, San Francisco, Calil. the biggest feline news in San Francisco. Further re- This notable ocelot trio is owned by Dion and Loralee ferences to Omar will be found on page 5 (True Romance Vigne. Omar's parents were "cover people" two of Trilby Ocelot), on Page 13 (The News) and on Page 6 years ago for the March-April, 1969 Newsletter (Vol. in the report of Exotic Cats of Northern California. 13, Number 2). Remember how mother Trilby was ---- Photo by Dion Vignee. PERSONAL OPINIONS on the Keeping oi Large Felidae as Pets By Robert E. Baudy Center Hill, Florida Not a weekgoes by that we do not receive some inquiry relating to the advisability of keeping large members of the cat family as pets. We have consequently decided to submit to Catherine Cisin, for possible publication in the LIOC Newsletter, our answers to the most commonly asked ques- tions on this subject, hoping that our own feeling on this LONG ISLAND OCELOT CLUB touchy subject might be of some help to would-be owners NEWSLETTER of large felines. -

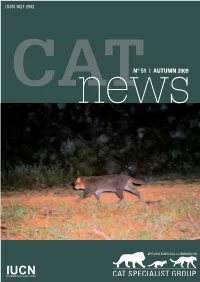

Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species

ISSN 1027-2992 CATnewsN° 51 | AUTUMN 2009 01 IUCNThe WorldCATnews Conservation 51Union Autumn 2009 news from around the world KRISTIN NOWELL1 Cats on the 2009 Red List of Threatened Species The IUCN Red List is the most authoritative lists participating in the assessment pro- global index to biodiversity status and is the cess. Distribution maps were updated and flagship product of the IUCN Species Survi- for the first time are being included on the val Commission and its supporting partners. Red List website (www.iucnredlist.org). Tex- As part of a recent multi-year effort to re- tual species accounts were also completely assess all mammalian species, the family re-written. A number of subspecies have Felidae was comprehensively re-evaluated been included, although a comprehensive in 2007-2008. A workshop was held at the evaluation was not possible (Nowell et al Oxford Felid Biology and Conservation Con- 2007). The 2008 Red List was launched at The fishing cat is one of the two species ference (Nowell et al. 2007), and follow-up IUCN’s World Conservation Congress in Bar- that had to be uplisted to Endangered by email with others led to over 70 specia- celona, Spain, and since then small changes (Photo A. Sliwa). Table 1. Felid species on the 2009 Red List. CATEGORY Common name Scientific name Criteria CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus C2a(i) ENDANGERED (EN) Andean cat Leopardus jacobita C2a(i) Tiger Panthera tigris A2bcd, A4bcd, C1, C2a(i) Snow leopard Panthera uncia C1 Borneo bay cat Pardofelis badia C1 Flat-headed -

Distemper, Extinction, and Vaccination of the Amur Tiger

Distemper, extinction, and vaccination of the FROM THE COVER Amur tiger Martin Gilberta,b,c,1, Nadezhda Sulikhand,e, Olga Uphyrkinad, Mikhail Goncharukf,g, Linda Kerleyf,h,i, Enrique Hernandez Castrob, Richard Reeveb, Tracie Seimonc, Denise McAloosec, Ivan V. Seryodkinj,k, Sergey V. Naidenkol, Christopher A. Davism, Gavin S. Wilkiem, Sreenu B. Vattipallym, Walt E. Adamsonb,m, Chris Hindsm, Emma C. Thomsonm, Brian J. Willettm, Margaret J. Hosiem, Nicola Loganm, Michael McDonaldm, Robert J. Ossiboffn, Elena I. Shevtsovae, Stepan Belyakino, Anna A. Yurlovao, Steven A. Osofskya, Dale G. Miquellec, Louise Matthewsb, and Sarah Cleavelandb aCornell Wildlife Health Center, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; bBoyd Orr Centre for Population and Ecosystem Health, Institute of Biodiversity Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, United Kingdom; cWildlife Conservation Society, Bronx, NY 10460; dFederal Scientific Center of the East Asia Terrestrial Biodiversity, Far Eastern Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok 690022, Russia; eLand of the Leopard National Park, Vladivostok 690068, Russia; fZoological Society of London, London NW1 4RY, United Kingdom; gPrimorskaya State Agricultural Academy, Ussuriisk 692510, Russia; hUnited Administration of Lazovsky Zapovednik and Zov Tigra National Park, Lazo 692890, Russia; iAutonomous Noncommercial Organization “Amur,” Lazo 692890, Russia; jPacific Geographical Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, -

Securing a Future for Amur Leopards and Tigers in Russia

Securing a Future for Amur Leopards and Tigers in Russia – VI 2018 Final Report Phoenix Fund 1 Securing a Future for Amur Leopards and Tigers in Russia – VI • 2018 Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Background ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Project Activities............................................................................................................................................ 4 SMART in five protected areas .................................................................................................................. 4 Annual workshop for educators ................................................................................................................ 8 Education in Khasan, Lazo, Terney and Vladivostok ................................................................................. 9 Tiger Day in Primorye .............................................................................................................................. 11 Art Contest .............................................................................................................................................. 13 Photo credits: PRNCO “Tiger “Centre”, Far Eastern Operational Customs Office, Land of the Leopard National Park, Alexander Ratnikov, and children's paintings -

Forum Big Cats in Borderlands: Challenges and Implications for Transboundary Conservation of Asian Leopards

Forum Big cats in borderlands: challenges and implications for transboundary conservation of Asian leopards M OHAMMAD S. FARHADINIA,SUSANA R OSTRO-GARCÍA,LIMIN F ENG J AN F. KAMLER,ANDREW S PALTON,ELENA S HEVTSOVA,IGOR K HOROZYAN M OHAMMED A L -DUAIS,JIANPING G E and D AVID W. MACDONALD Abstract Large carnivores have extensive spatial require- for the survival of these subspecies. Recent listing of the ments, with ranges that often span geopolitical borders. leopard in the Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Consequently, management of transboundary populations Migratory Species of Wild Animals is important, but more is subject to several political jurisdictions, often with hetero- international collaboration is needed to conserve these sub- geneity in conservation challenges. In continental Asia there species. We provide a spatial framework with which range are four threatened leopard subspecies with transboundary countries and international agencies could establish trans- populations spanning countries: the Persian Panthera boundary cooperation for conserving threatened leopards pardus saxicolor, Indochinese P. pardus delacouri, Arabian in Asia. P. pardus nimr and Amur P. pardus orientalis leopards. We Keywords Asia, Bonn Convention on the Conservation of reviewed the status of these subspecies and examined the Migratory Species of Wild Animals, borderland, conserva- challenges to, and opportunities for, their conservation. tion geopolitics, leopard, Panthera pardus, security fence, The Amur and Indochinese leopards have the majority transboundary (–%) of their remaining range in borderlands, and the Persian and Arabian leopards have –% of their re- maining ranges in borderlands. Overall, in of countries the majority of the remaining leopard range is in border- lands, and thus in most countries conservation of these Introduction subspecies is dependent on transboundary collaboration.