Long-Term Amur Tiger Research and Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia's Tigers ×

This website would like to remind you: Your browser (Apple Safari 4) is out of date. Update your browser for more × security, comfort and the best experience on this site. Video MEDIA SPOTLIGHT Russia's Tigers For the complete videos with media resources, visit: http://education.nationalgeographic.com/media/russias-tigers/ The Siberian tiger is the world's largest cat. But with only 400 left in the wild, this rare giant is in danger of extinction due to poaching and habitat loss. Join Wild Chronicles on an expedition to Russia, where researchers have the rare opportunity to study this elusive species up close at a wildlife sanctuary. Hopefully their work will help protect these mighty giants. QUESTIONS Why does the Siberian tiger have a thicker coat than other tigers in southern Asia? The winters in Siberia are extremely cold. Why are these Siberian tigers difficult to study in the wild? The Siberian rough terrain and the vast distances the tigers travel (anywhere from 200-500 square miles or 500- 1,300 square kilometers) makes studying them difficult. Besides poaching the tigers, how else are poachers harming these tigers? The poachers are also poaching the tiger's food supply, like elk and wild boar. Why do you think it so important to protect and save the Siberian tiger? Siberian tigers are the most rare subspecies of tiger and the largest tiger subspecies in the world. It is important to save the Siberian tiger because they are beautiful and strong creatures. In some cultures, like the Tungusic peoples (living in Siberia), the Siberian tiger is revered as a near-deity, or god. -

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard Under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes Ivan Csiszar, Tatiana Loboda, Dale Miquelle, Nancy Sherman, Hank Shugart, Tim Stephens. The Study Region Primorsky Krai has a large systems of reserves and protected areas. Tigers are wide ranging animals and are not necessarily contained by these reserves. Tigers areSiberian in a state Tigers of prec areipitous now restricted decline worldwide. Yellow is tothe Primorsky range in 1900;Krai in red the is Russian the current or potential habitat, todayFar East Our (with study a possible focuses few on the in Amur Tiger (PantheraNorthern tigris altaica China).), the world’s largest “big cat”. The Species of Panthera Amur Leopard (P. pardus orientalis) Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) One of the greatest threats to tigers is loss of habitat and lack of adequate prey. Tiger numbers can increase rapidly if there is sufficient land, prey, water, and sheltered areas to give birth and raise young. The home range territory Status: needed Critically depends endangered on the Status: Critically endangered (less than (less than 50 in the wild) 400 in the wild) Females: 62 – 132density lbs; of prey. Females: Avg. about 350 lbs., to 500 lbs.; Males: 82 – 198 lbs Males: Avg. about 500 lbs., to 800 lbs. Diet: Roe deer (Capreolus Key prey: Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), pygargus), Sika Deer, Wild Boar, Wild Boar (Sus scrofa), Sika Deer Hares, other small mammals (Cervus nippon), small mammals The Prey of Panthera Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Called Elk or Wapiti in the US. The Prey of Panthera Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) The Prey of Panthera Roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) The Prey of Panthera Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Amur Tigers also feed occasionally on Moose (Alces alces). -

Amur Leopard and Siberian Tiger Combined Tours

Secret Cats of the Russian Far East Destination: Ussuri & Primorie, Russia Season: mid Nov – mid Mar Expert guidance from one of Russia’s leading Siberian Tiger conservationists Exclusive access to a specialist photography hide for the Amur leopard Contribute directly to the ongoing study and research of wild Siberian Tigers Explore some of the most pristine and beautiful forests in the world in winter Track wild Siberian Tigers and piece together their behaviours and movements Dates: Prices (2018-19 season): (1) Group Tour: 19th Nov – 10th Dec 2018 Group Tour - 2018 (2) Group Tour: 27th Nov – 18th Dec 2018 £7,305 per person (3) Group Tour: 12th Feb – 5th Mar 2019 *single supplement £100 (4) Group Tour: 20th Feb – 13th Mar 2019 Group Tour - 2019 (5) Group Tour: 19th Nov – 10th Dec 2019 th th £7,425 per person (6) Group Tour: 27 Nov – 18 Dec 2019 *single supplement £100 Scheduled Group Tour information: Group Dates as a Private Tour The above dates are for combining our Siberian Tiger Winter Tour and our Amur Leopard Photography tour. £16,995 for a solo traveller We run the Amur leopard tour both at the start and end £8,495 per person (2 people) of the Siberian tiger tour. So the itinerary below is for tours where the leopard section starts first, however Private Tour on Other Dates some of the above dates start with the tiger section and £12,150 for a solo traveller then go to the leopards. There is no change to the itinerary (it is just reversed – and your start and end £5,995 per person (2 people) points are different). -

Final Report ______January 01 –December 31, 2003

Phoenix Final Report ____________________________________________________________________________________ January 01 –December 31, 2003 FINAL REPORT January 01 – December 31, 2003 The Grantor: Save the Tiger Fund Project No: № 2002 – 0301 – 034 Project Name: “Operation Amba Siberian Tiger Protection – III” The Grantee: The Phoenix Fund Report Period: January 01 – December 31, 2003 Project Period: January 01 – December 31, 2003 The objective of this project is to conserve endangered wildlife in the Russian Far East and ensure long-term survival of the Siberian tiger and its prey species through anti-poaching activities of Inspection Tiger and non-governmental investigation teams, human-tiger conflict resolution and environmental education. To achieve effective results in anti-poaching activity Phoenix encourage the work of both governmental and public rangers. I. KHABAROVSKY AND SPECIAL EMERGENCY RESPONSE TEAMS OF INSPECTION TIGER This report will highlight the work and outputs of Khabarovsky anti-poaching team and Special Emergency Response team that cover the south of Khabarovsky region and the whole territory of Primorsky region. For the reported period, the Khabarovsky team has documented 47 cases of ecological violations; Special Emergency Response team has registered 25 conflict tiger cases. Tables 1 and 2 show the results of both teams. Conflict Tiger Cases The Special Emergency Response Team works on the territory of Primorsky region and south of Khabarovsky region. For the reported period, 25 conflict tiger cases have been registered and investigated by the Special Emergency Response team of Inspection Tiger, one of them transpired to be a “false alarm”. 1) On January 04, 2003 the Special Emergency Response team received information from gas filling station workers that in the vicinity of Terney village they had seen a tiger with a killed dog crossing Terney-Plastun route. -

2012 WCS Report Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in The

Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in the Russian Far East Final Report to The Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA) from the WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY (WCS) March 2012 Project Location: Southwest Primorskii Krai, Russian Far East Grant Period: July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Project Coordinators: Dale Miquelle, PhD Alexey Kostyria, PhD E: [email protected] E: [email protected] SUMMARY From March to June 2011 we recorded 156 leopard photographs, bringing our grand total of leopard camera trap photographs (2002-present) to 756. In 2011 we recorded 17 different leopards on our study area, the most ever in nine years of monitoring. While most of these likely represent transients, it is still a positive sign that the population is reproducing and at least maintaining itself. Additionally, camera trap monitoring in an adjacent unit just south of our study area reported 12 leopards, bringing the total minimum number of leopards to 29. Collectively, these results suggest that the total number of leopards in the Russian Far East is presently larger than the 30 individuals usually reported. We also recorded 7 tigers on the study area, including 3 cubs. The number of adult tigers on the study area has remained fairly steady over all nine years of the monitoring program. INTRODUCTION The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is the northern-most of the nine extant subspecies (Miththapala et al., 1996; Uphyrkina et al., 2001), with a very small global distribution in the southernmost corner of the Russian Far East (two counties in Primorye Province), and in neighboring Jilin Province, China. -

Sea of Okhotsk: Seals, Seabirds and a Legacy of Sorrow

SEA OF OKHOTSK: SEALS, SEABIRDS AND A LEGACY OF SORROW Little known outside of Russia and seldom visited by westerners, Russia's Sea of Okhotsk dominates the Northwest Pacific. Bounded to the north and west by the Russian continent and the Kamchatka Peninsula to the east, with the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin Island guarding the southern border, it is almost landlocked. Its coasts were once home to a number of groups of indigenous people: the Nivkhi, Oroki, Even and Itelmen. Their name for this sea simply translates as something like the ‘Sea of Hunters' or ‘Hunters Sea', perhaps a clue to the abundance of wildlife found here. In 1725, and again in 1733, the Russian explorer Vitus Bering launched two expeditions from the town of Okhotsk on the western shores of this sea in order to explore the eastern coasts of the Russian Empire. For a long time this town was the gateway to Kamchatka and beyond. The modern make it an inhospitable place. However the lure of a rich fishery town of Okhotsk is built near the site of the old town, and little and, more recently, oil and gas discoveries means this sea is has changed over the centuries. Inhabitants now have an air still being exploited, so nothing has changed. In 1854, no fewer service, but their lives are still dominated by the sea. Perhaps than 160 American and British whaling ships were there hunting no other sea in the world has witnessed as much human whales. Despite this seemingly relentless exploitation the suffering and misery as the Sea of Okhotsk. -

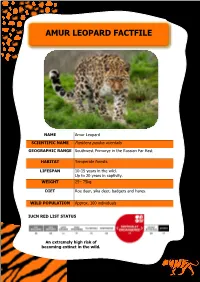

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Tiger Conservation in the Russian Far East

Tiger Conservation in the Russian Far East Background The Russian Far East is home to the world’s only remaining population of wild Amur, or Siberian tigers, Panthera tigris altaica (Figures 1&2). Population surveys conducted in 2005 estimated this to be between 430 – 500 individuals (Miquelle et al. 2007), but since then numbers have declined even further, based both on data from the Amur Tiger Monitoring Program (a 13 year collaboration between WCS and Russian partners), and official government reports (Global Tiger Recovery Program 2010). An increase in poaching (Figure 3), combined with habitat loss, is the key driver of this downward trend. Furthermore, the appearance of disease-related deaths in tiger populations represents a new threat of unknown dimensions and one which is only just being acknowledged. WCS-Russia’s overall tiger program in the Russian Far East The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) has been active in the Russian Far East since 1992, working to conserve landscape species including Amur tigers, Far Eastern leopards and Blakiston’s fish owls, whose survival ultimately requires the conservation of the forest ecosystem as a whole. Our science-based approach, which relies on the findings of our research to design effective conservation interventions, emphasizes close collaboration with local stakeholders to improve wildlife and habitat management, both within and outside of protected areas, inclusion of local communities in resolving resource use issues, and the application of robust monitoring programs to understand the effectiveness of conservation interventions. Poaching of tigers and their prey appears to be the number one threat to tigers in the Russian Far East. -

Leopard (Panthera Pardus) Status, Distribution, and the Research Efforts Across Its Range

Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range Andrew P. Jacobson1,2,3, Peter Gerngross4, Joseph R. Lemeris Jr.3, Rebecca F. Schoonover3, Corey Anco5, Christine Breitenmoser- Wu¨rsten6, Sarah M. Durant1,7, Mohammad S. Farhadinia8,9, Philipp Henschel10, Jan F. Kamler10, Alice Laguardia11, Susana Rostro-Garcı´a9, Andrew B. Stein6,12 and Luke Dollar3,13,14 1 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, United Kingdom 2 Department of Geography, University College London, London, United Kingdom 3 Big Cats Initiative, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., United States 4 BIOGEOMAPS, Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Biological Sciences, Fordham University, Bronx, NY, United States 6 IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, c/o KORA, Bern, Switzerland 7 Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx Zoo, Bronx, NY, United States 8 Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), Tehran, Iran 9 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, The Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Tubney, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom 10 Panthera, New York, NY, United States 11 The Wildlife Institute, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 12 Landmark College, Putney, VT, United States 13 Department of Biology, Pfeiffer University, Misenheimer, NC, United States 14 Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States ABSTRACT The leopard’s (Panthera pardus) broad geographic range, remarkable adaptability, and secretive nature have contributed to a misconception that this species might not be severely threatened across its range. We find that not only are several subspecies and regional populations critically endangered but also the overall range loss is greater than the average for terrestrial large carnivores. 31 December 2015 Submitted To assess the leopard’s status, we compile 6,000 records at 2,500 locations Accepted 5 April 2016 Published 4May2016 from over 1,300 sources on its historic (post 1750) and current distribution. -

HIDDEN in PLAIN SIGHT China's Clandestine Tiger Trade ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS

HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT China's Clandestine Tiger Trade ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS This report was written by Environmental Investigation Agency. 1 EIA would like to thank the Rufford Foundation, SUMMARY the David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation, Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust and Save Wild Tigers for their support in making this work possible. 3 INTRODUCTION Special thanks to our colleagues “on the frontline” in tiger range countries for their information, 5 advice and inspiration. LEGAL CONTEXT ® EIA uses IBM i2 intelligence analysis software. 6 INVESTIGATION FINDINGS Report design by: www.designsolutions.me.uk 12 TIGER FARMING February 2013 13 PREVIOUS EXPOSÉS 17 STIMULATING POACHING OF WILD ASIAN BIG CATS 20 MIXED MESSAGES 24 SOUTH-EAST ASIA TIGER FARMS 25 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 26 APPENDICES 1) TABLE OF LAWS AND REGULATIONS RELATING TO TIGERS IN CHINA 2) TIGER FARMING TIMELINE ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY (EIA) 62/63 Upper Street, London N1 0NY, UK Tel: +44 (0) 20 7354 7960 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7354 7961 email: [email protected] www.eia-international.org EIA US P.O.Box 53343 Washington DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 483 6621 Fax: +1 202 986 8626 email: [email protected] www.eia-global.org Front cover image © Robin Hamilton All images © EIA unless otherwise specified © Michael Vickers/www.tigersintheforest.co.uk SUMMARY Undercover investigations and a review of available Chinese laws have revealed that while China banned tiger bone trade for medicinal uses in 1993, it has encouraged the growth of the captive-breeding of tigers to supply a quietly expanding legal domestic trade in tiger skins. -

Amur (Siberian) Tiger Panthera Tigris Altaica Tiger Survival

Amur (Siberian) Tiger Panthera tigris altaica Tiger Survival - It is estimated that only 350-450 Amur (Siberian) tigers remain in the wild although there are 650 in captivity. Tigers are poached for their bones and organs, which are prized for their use in traditional medicines. A single tiger can be worth over $15,000 – more than most poor people in the region make over years. Recent conservation efforts have increased the number of wild Siberian tigers but continued efforts will be needed to ensure their survival. Can You See Me Now? - Tigers are the most boldly marked cats in the world and although they are easy to see in most zoo settings, their distinctive stripes and coloration provides the camouflage needed for a large predator in the wild. The pattern of stripes on a tigers face is as distinctive as human fingerprints – no two tigers have exactly the same stripe pattern. Classification The Amur tiger is one of 9 subspecies of tiger. Three of the 9 subspecies are extinct, and the rest are listed as endangered or critically endangered by the IUCN. Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Panthera Species: tigris Subspecies: altaica Distribution The tiger’s traditional range is through southeastern Siberia, northeast China, the Russian Far East, and northern regions of North Korea. Habitat Snow-covered deciduous, coniferous and scrub forests in the mountains. Physical Description • Males are 9-12 feet (2.7-3.6 m) long including a two to three foot (60-90 cm) tail; females are up to 9 feet (2.7 m) long.