Forum Big Cats in Borderlands: Challenges and Implications for Transboundary Conservation of Asian Leopards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panthera Pardus, Leopard

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T15954A5329380 Panthera pardus, Leopard Assessment by: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser- Wursten, C. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser-Wursten, C. 2008. Panthera pardus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15954A5329380. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15954A5329380.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Carnivora Felidae Taxon Name: Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) Synonym(s): • Felis pardus Linnaeus, 1758 Regional Assessments: • Mediterranean Infra-specific Taxa Assessed: • Panthera pardus ssp. -

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard Under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes Ivan Csiszar, Tatiana Loboda, Dale Miquelle, Nancy Sherman, Hank Shugart, Tim Stephens. The Study Region Primorsky Krai has a large systems of reserves and protected areas. Tigers are wide ranging animals and are not necessarily contained by these reserves. Tigers areSiberian in a state Tigers of prec areipitous now restricted decline worldwide. Yellow is tothe Primorsky range in 1900;Krai in red the is Russian the current or potential habitat, todayFar East Our (with study a possible focuses few on the in Amur Tiger (PantheraNorthern tigris altaica China).), the world’s largest “big cat”. The Species of Panthera Amur Leopard (P. pardus orientalis) Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) One of the greatest threats to tigers is loss of habitat and lack of adequate prey. Tiger numbers can increase rapidly if there is sufficient land, prey, water, and sheltered areas to give birth and raise young. The home range territory Status: needed Critically depends endangered on the Status: Critically endangered (less than (less than 50 in the wild) 400 in the wild) Females: 62 – 132density lbs; of prey. Females: Avg. about 350 lbs., to 500 lbs.; Males: 82 – 198 lbs Males: Avg. about 500 lbs., to 800 lbs. Diet: Roe deer (Capreolus Key prey: Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), pygargus), Sika Deer, Wild Boar, Wild Boar (Sus scrofa), Sika Deer Hares, other small mammals (Cervus nippon), small mammals The Prey of Panthera Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Called Elk or Wapiti in the US. The Prey of Panthera Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) The Prey of Panthera Roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) The Prey of Panthera Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Amur Tigers also feed occasionally on Moose (Alces alces). -

Opportunity for Thailand's Forgotten Tigers: Assessment of the Indochinese Tiger Panthera Tigris Corbetti and Its Prey with Camera-Trap Surveys

Opportunity for Thailand's forgotten tigers: assessment of the Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti and its prey with camera-trap surveys E RIC A SH, Ż ANETA K ASZTA,ADISORN N OOCHDUMRONG,TIM R EDFORD P RAWATSART C HANTEAP,CHRISTOPHER H ALLAM,BOONCHERD J AROENSUK S OMSUAN R AKSAT,KANCHIT S RINOPPAWAN and D AVID W. MACDONALD Abstract Dramatic population declines threaten the En- Keywords Bos gaurus, distribution, Dong Phayayen-Khao dangered Indochinese tiger Panthera tigris corbetti with ex- Yai Forest Complex, Indochinese tiger, Panthera tigris tinction. Thailand now plays a critical role in its conservation, corbetti, prey abundance, Rusa unicolor, Sus scrofa as there are few known breeding populations in other Supplementary material for this article is available at range countries. Thailand’s Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai For- doi.org/./S est Complex is recognized as an important tiger recovery site, but it remains poorly studied. Here, we present results from the first camera-trap study focused on tigers and im- plemented across all protected areas in this landscape. Our Introduction goal was to assess tiger and prey populations across the five protected areas of this forest complex, reviewing discernible he tiger Panthera tigris has suffered catastrophic de- patterns in rates of detection. We conducted camera-trap Tclines in its population (%) and habitat (%) over surveys opportunistically during –. We recorded the past century (Nowell & Jackson, ; Goodrich et al., , detections of tigers in , camera-trap nights. ; Wolf & Ripple, ). Evidence suggests only source Among these were at least adults and six cubs/juveniles sites (i.e. sites with breeding populations that have the po- from four breeding females. -

2012 WCS Report Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in The

Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in the Russian Far East Final Report to The Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA) from the WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY (WCS) March 2012 Project Location: Southwest Primorskii Krai, Russian Far East Grant Period: July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Project Coordinators: Dale Miquelle, PhD Alexey Kostyria, PhD E: [email protected] E: [email protected] SUMMARY From March to June 2011 we recorded 156 leopard photographs, bringing our grand total of leopard camera trap photographs (2002-present) to 756. In 2011 we recorded 17 different leopards on our study area, the most ever in nine years of monitoring. While most of these likely represent transients, it is still a positive sign that the population is reproducing and at least maintaining itself. Additionally, camera trap monitoring in an adjacent unit just south of our study area reported 12 leopards, bringing the total minimum number of leopards to 29. Collectively, these results suggest that the total number of leopards in the Russian Far East is presently larger than the 30 individuals usually reported. We also recorded 7 tigers on the study area, including 3 cubs. The number of adult tigers on the study area has remained fairly steady over all nine years of the monitoring program. INTRODUCTION The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is the northern-most of the nine extant subspecies (Miththapala et al., 1996; Uphyrkina et al., 2001), with a very small global distribution in the southernmost corner of the Russian Far East (two counties in Primorye Province), and in neighboring Jilin Province, China. -

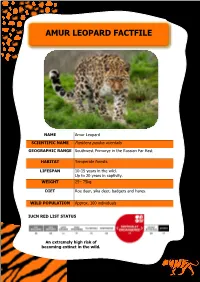

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Panthera Pardus) and Its Extinct Eurasian Populations Johanna L

Paijmans et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018) 18:156 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1268-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) and its extinct Eurasian populations Johanna L. A. Paijmans1* , Axel Barlow1, Daniel W. Förster2, Kirstin Henneberger1, Matthias Meyer3, Birgit Nickel3, Doris Nagel4, Rasmus Worsøe Havmøller5, Gennady F. Baryshnikov6, Ulrich Joger7, Wilfried Rosendahl8 and Michael Hofreiter1 Abstract Background: Resolving the historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) is a complex issue, because patterns inferred from fossils and from molecular data lack congruence. Fossil evidence supports an African origin, and suggests that leopards were already present in Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene. Analysis of DNA sequences however, suggests a more recent, Middle Pleistocene shared ancestry of Asian and African leopards. These contrasting patterns led researchers to propose a two-stage hypothesis of leopard dispersal out of Africa: an initial Early Pleistocene colonisation of Asia and a subsequent replacement by a second colonisation wave during the Middle Pleistocene. The status of Late Pleistocene European leopards within this scenario is unclear: were these populations remnants of the first dispersal, or do the last surviving European leopards share more recent ancestry with their African counterparts? Results: In this study, we generate and analyse mitogenome sequences from historical samples that span the entire modern leopard distribution, as well as from Late Pleistocene remains. We find a deep bifurcation between African and Eurasian mitochondrial lineages (~ 710 Ka), with the European ancient samples as sister to all Asian lineages (~ 483 Ka). The modern and historical mainland Asian lineages share a relatively recent common ancestor (~ 122 Ka), and we find one Javan sample nested within these. -

Carnivore Hotspots in Peninsular Malaysia and Their Landscape

1 Carnivore hotspots in Peninsular Malaysia and their 2 landscape attributes 3 Shyamala Ratnayeke1*¶, Frank T. van Manen2¶, Gopalasamy Reuben Clements1&, Noor Azleen 4 Mohd Kulaimi3&, Stuart P. Sharp4& 5 1Department of Biological Sciences, Sunway University, Malaysia 6 7 2U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center, Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, Bozeman, 8 MT 59715, USA 9 10 3Ex-Situ Conservation Division, Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Malaysia 11 12 4Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YQ, UK 13 14 15 16 *Corresponding author 17 Email: [email protected] 18 19 ¶SR and FTVM are joint senior authors 20 &These authors also contributed equally to this work 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Disclaimer: This draft manuscript is distributed solely for purposes of scientific peer review. Its content is 34 deliberative and pre-decisional, so it must not be disclosed or released by reviewers. Because the 35 manuscript has not yet been approved for publication by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), it does not 36 represent any official USGS finding or policy. 37 Abstract 38 Mammalian carnivores play a vital role in ecosystem functioning. However, they are prone to 39 extinction because of low population densities and growth rates, large area requirements, and 40 high levels of persecution or exploitation. In tropical biodiversity hotspots such as Peninsular 41 Malaysia, rapid conversion of natural habitats threatens the persistence of this vulnerable 42 group of animals. Here, we carried out the first comprehensive literature review on 31 43 carnivore species reported to occur in Peninsular Malaysia and updated their probable 44 distribution. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Leopard (Panthera Pardus) Status, Distribution, and the Research Efforts Across Its Range

Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range Andrew P. Jacobson1,2,3, Peter Gerngross4, Joseph R. Lemeris Jr.3, Rebecca F. Schoonover3, Corey Anco5, Christine Breitenmoser- Wu¨rsten6, Sarah M. Durant1,7, Mohammad S. Farhadinia8,9, Philipp Henschel10, Jan F. Kamler10, Alice Laguardia11, Susana Rostro-Garcı´a9, Andrew B. Stein6,12 and Luke Dollar3,13,14 1 Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, United Kingdom 2 Department of Geography, University College London, London, United Kingdom 3 Big Cats Initiative, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., United States 4 BIOGEOMAPS, Vienna, Austria 5 Department of Biological Sciences, Fordham University, Bronx, NY, United States 6 IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, c/o KORA, Bern, Switzerland 7 Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx Zoo, Bronx, NY, United States 8 Iranian Cheetah Society (ICS), Tehran, Iran 9 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, The Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Tubney, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom 10 Panthera, New York, NY, United States 11 The Wildlife Institute, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 12 Landmark College, Putney, VT, United States 13 Department of Biology, Pfeiffer University, Misenheimer, NC, United States 14 Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States ABSTRACT The leopard’s (Panthera pardus) broad geographic range, remarkable adaptability, and secretive nature have contributed to a misconception that this species might not be severely threatened across its range. We find that not only are several subspecies and regional populations critically endangered but also the overall range loss is greater than the average for terrestrial large carnivores. 31 December 2015 Submitted To assess the leopard’s status, we compile 6,000 records at 2,500 locations Accepted 5 April 2016 Published 4May2016 from over 1,300 sources on its historic (post 1750) and current distribution. -

Historical Biogeography of the Leopard (Panthera Pardus) and Its Extinct Eurasian Populations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Copenhagen University Research Information System Historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) and its extinct Eurasian populations Paijmans, Johanna L. A.; Barlow, Axel; Förster, Daniel W.; Henneberger, Kirstin; Meyer, Matthias; Nickel, Birgit; Nagel, Doris; Worsøe Havmøller, Rasmus; Baryshnikov, Gennady F.; Joger, Ulrich; Rosendahl, Wilfried; Hofreiter, Michael Published in: BMC Evolutionary Biology DOI: 10.1186/s12862-018-1268-0 Publication date: 2018 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Document license: CC BY Citation for published version (APA): Paijmans, J. L. A., Barlow, A., Förster, D. W., Henneberger, K., Meyer, M., Nickel, B., ... Hofreiter, M. (2018). Historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) and its extinct Eurasian populations. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1268-0 Download date: 09. Apr. 2020 Paijmans et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2018) 18:156 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-018-1268-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) and its extinct Eurasian populations Johanna L. A. Paijmans1* , Axel Barlow1, Daniel W. Förster2, Kirstin Henneberger1, Matthias Meyer3, Birgit Nickel3, Doris Nagel4, Rasmus Worsøe Havmøller5, Gennady F. Baryshnikov6, Ulrich Joger7, Wilfried Rosendahl8 and Michael Hofreiter1 Abstract Background: Resolving the historical biogeography of the leopard (Panthera pardus) is a complex issue, because patterns inferred from fossils and from molecular data lack congruence. Fossil evidence supports an African origin, and suggests that leopards were already present in Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene. Analysis of DNA sequences however, suggests a more recent, Middle Pleistocene shared ancestry of Asian and African leopards. -

2019 Cat Specialist Group Report

IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group 2019 Report Christine Breitenmoser Urs Breitenmoser Co-Chairs Mission statement Research activities: develop camera trapping Christine Breitenmoser (1) Cat Manifesto database which feeds into the Global Mammal Urs Breitenmoser (2) (www.catsg.org/index.php?id=44). Assessment and the IUCN SIS database. Technical advice: (1) develop Cat Monitoring Guidelines; (2) conservation of the Wild Cat Red List Authority Coordinator Projected impact for the 2017-2020 (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: review of the Tabea Lanz (1) quadrennium conservation status and assessment of conser- By 2020, we will have implemented the Assess- Location/Affiliation vation activities. Plan-Act (APA) approach for additional cat (1) Plan KORA, Muri b. Bern, Switzerland species. We envision improving the status (2) Planning: (1) revise the National Action Plan for FIWI/Universtiät Bern and KORA, Muri b. assessments and launching new conservation Asiatic Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus) in Bern, Switzerland planning processes. These conservation initia- Iran; (2) participate in Javan Leopard (Panthera tives will be combined with communicational pardus melas) workshop; (3) facilitate lynx Number of members and educational programmes for people and workshop; (4) develop conservation strategy for 193 institutions living with these species. the Pallas’s Cat (Otocolobus manul); (5) plan- ning for the Leopard in Africa and Southeast Social networks Targets for the 2017-2020 quadrennium Asia; (6) updating and coordination for the Lion Facebook: IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group Assess (Panthera leo) Conservation Strategy; (7) facil- Website: www.catsg.org Capacity building: attend and facilitate a work- itate a workshop to develop a conservation shop to develop recommendations for the strategy for the Jaguar (Panthera onca) in a conservation of the Persian Leopard (Panthera number of neglected countries in collaboration pardus tulliana) in July 2020. -

Ranging Behavior of Persian Leopards Along the Iran-Turkmenistan Borderland

RESEARCH ARTICLE Anchoring and adjusting amidst humans: Ranging behavior of Persian leopards along the Iran-Turkmenistan borderland Mohammad S. Farhadinia1,2*, Paul J. Johnson1, David W. Macdonald1, Luke T. B. Hunter3,4 1 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Recanati-Kaplan Centre, Tubney House, Oxfordshire, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2 Future4Leopards Foundation, Tehran, Iran, 3 Panthera, New York, New York, United States of America, 4 School of Life Sciences, Westville Campus, a1111111111 University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Understanding the space use and movement ecology of apex predators, particularly in mosaic landscapes encompassing different land-uses, is fundamental for formulating effec- OPEN ACCESS tive conservation policy. The top extant big cat in the Middle East and the Caucasus, the Citation: Farhadinia MS, Johnson PJ, Macdonald DW, Hunter LTB (2018) Anchoring and adjusting Persian leopard Panthera pardus saxicolor, has disappeared from most of its historic range. amidst humans: Ranging behavior of Persian Its spatial ecology in the areas where it remains is almost unknown. Between September leopards along the Iran-Turkmenistan borderland. 2014 and May 2017, we collared and monitored six adult leopards (5 males and 1 female) PLoS ONE 13(5): e0196602. https://doi.org/ using GPS-satellite Iridium transmitters in Tandoureh National Park (355 km2) along the 10.1371/journal.pone.0196602 Iran-Turkmenistan borderland. Using auto-correlated Kernel density estimation based on a Editor: Matthias StoÈck, Leibniz-Institute of continuous-time stochastic process for relocation data, we estimated a mean home range of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, 2 GERMANY 103.4 ± SE 51.8 km for resident males which is larger than has been observed in other studies of Asian leopards.