Chapter XI: the Problem of the Palmette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Fragmenti's of the Parthenon Acroteria

NEW FRAGMENTI'SOF THE PARTHENON ACROTERIA (PLATE 56) WOULD like to call attention to two new fragments of the floral acroteria of the Parthenon found recently in the storerooms of the Athens Acropolis Museum.' They are both palmette petals and join break-on-break to Acropolis Museum inv. no. 3442, a fragment from the right crowning half-palmette of Acroterion A (P1. 56: a, b, with new fragments in place).2 The new fragments are from the outermost petals of the crowning palmette and represent parts of these petals not preserved in the fragment of the corresponding left half-palmette of A, Acropolis Museum inv. no. 3446.3 The position of the outer petals is now known for the greater part of their length and their tips can be restored with increased surety. The larger of the new fragments shows clearly that the petal of which it is a part lies in a double curve, the lower part of the petal bending away from, the upper part toward the median line. This double curve, a characteristic of the so-called flame palmette, has been assumed in reconstructions of the Parthenon acroteria on the basis of later parallels; it is attested by the new fragments for the first time. 1 I am grateful to Dr. George Dontas, Ephor of the Acropolis, for permission to publish these fragments, and to Mrs. Maria Brouskari for generously facilitating my work in the museum. I am grateful also to Eugene Vanderpool, Jr. for the accompanying photographs, and to William B. Dinsmoor, Jr. for the new reconstruction of the crowning palmette. -

Discover the Styles and Techniques of French Master Carvers and Gilders

LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F SEPTEMBER 15, 2015–JANUARY 3, 2016 What makes a frame French? Discover the styles and techniques of French master carvers and gilders. This magnificent frame, a work of art in its own right, weighing 297 pounds, exemplifies French style under Louis XV (reigned 1723–1774). Fashioned by an unknown designer, perhaps after designs by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (French, 1695–1750), and several specialist craftsmen in Paris about 1740, it was commissioned by Gabriel Bernard de Rieux, a powerful French legal official, to accentuate his exceptionally large pastel portrait and its heavy sheet of protective glass. On this grand scale, the sweeping contours and luxuriously carved ornaments in the corners and at the center of each side achieve the thrilling effect of sculpture. At the top, a spectacular cartouche between festoons of flowers surmounted by a plume of foliage contains attributes symbolizing the fair judgment of the sitter: justice (represented by a scale and a book of laws) and prudence (a snake and a mirror). PA.205 The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2015 J. Paul Getty Trust LOUIS STYLE rench rames F 1610–1792F Frames are essential to the presentation of paintings. They protect the image and permit its attachment to the wall. Through the powerful combination of form and finish, frames profoundly enhance (or detract) from a painting’s visual impact. The early 1600s through the 1700s was a golden age for frame making in Paris during which functional surrounds for paintings became expressions of artistry, innovation, taste, and wealth. The primary stylistic trendsetter was the sovereign, whose desire for increas- ingly opulent forms of display spurred the creative Fig. -

The Two-Piece Corinthian Capital and the Working Practice of Greek and Roman Masons

The two-piece Corinthian capital and the working practice of Greek and Roman masons Seth G. Bernard This paper is a first attempt to understand a particular feature of the Corinthian order: the fashioning of a single capital out of two separate blocks of stone (fig. 1).1 This is a detail of a detail, a single element of one of the most richly decorated of all Classical architec- tural orders. Indeed, the Corinthian order and the capitals in particular have been a mod- ern topic of interest since Palladio, which is to say, for a very long time. Already prior to the Second World War, Luigi Crema (1938) sug- gested the utility of the creation of a scholarly corpus of capitals in the Greco-Roman Mediter- ranean, and especially since the 1970s, the out- flow of scholarly articles and monographs on the subject has continued without pause. The basis for the majority of this work has beenformal criteria: discussion of the Corinthian capital has restedabove all onstyle and carving technique, on the mathematical proportional relationships of the capital’s design, and on analysis of the various carved components. Much of this work carries on the tradition of the Italian art critic Giovanni Morelli whereby a class of object may be reduced to an aggregation of details and elements of Fig. 1: A two-piece Corinthian capital. which, once collected and sorted, can help to de- Flavian period repairs to structures related to termine workshop attributions, regional varia- it on the west side of the Forum in Rome, tions,and ultimatelychronological progressions.2 second half of the first century CE (photo by author). -

October 1893

ENTRANCE TO THE CITY HALL, COLOGNE. TTbe VOL. III. OCTOBER-DECEMBER, 1893. NO. 2. THE PROBLEM OF NATIONAL AMERICAN ARCHITECTURE. I. THE QUESTION STATED. HAT is to be the must in due time be developed, in the character of the peculiar circumstances of American style of artistic progress, a particular variety of that architectural de- artistic treatment of building which is sign which sooner one of the instincts of mankind, is a or later is to be- proposition that is scarcely open to come established debate. The question before us there- in the United fore is simply this: Considering what States as a national style ? Of course these peculiar circumstances are, and this is a to to those natural speculative question ; but, having regard laws, American architects and connoisseurs, how far can we foresee the outcome? it is not merely an extremely interest- Is this American originality likely to be ing one, it is a highly important one, great or small; essential or not; good, and indeed a practical problem for bad, or indifferent; of speedy achieve- daily consideration. ment or slow; permanent or evanescent? Americans may ask whether it is not for themselves to solve this problem, II. A PECULIAR CONTROVERSY IN without any help from friends, however ENGLAND. friendly, in the Old World a world, moreover, which to many persons in It may be well to premise that there these days seems somewhat effete in is at the present moment a very pecul- many ways, and confessedly, amongst iar and somewhat acrimonious contro- the rest, not up to the mark in archi- versy agitating the architectural profes- tecture. -

Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, Ca

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Anthropology Honors College 5-2013 Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, ca. 2500-2000 B.C.E. Donovan Adams University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_anthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Donovan, "Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, ca. 2500-2000 B.C.E." (2013). Anthropology. 9. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_anthro/9 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cypriot Religion of the Early Bronze Age: Insular and Transmitted Ideologies, ca. 2500-2000 B.C.E. An honors thesis presented to the Department of Anthropology, University at Albany, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of requirements for graduation with Honors in Anthropology and graduation from the Honors College. Donovan Adams Research Advisor: Stuart Swiny, Ph.D. March 2013 1 Abstract The Early Bronze Age of Cyprus is not a very well understood chronological period of the island for a variety of reasons. These include: the inaccessibility of the northern part of the island after the Turkish invasion, the lack of a written language, and the fragility of Cypriot artifacts. Many aspects of protohistoric Cypriot life have become more understood, such as: the economic structure, social organization, and interactions between Cyprus and Anatolia. -

THE PASSAGE of LOTUS ORNAMENT from EGYPTIAN to THAI a Study of Origin, Metamorphosis, and Influence on Traditional Thai Decorative Ornament

The Bulletin of JSSD Vol.1 No.2 pp.1-2(2000) Original papers Received November 13, 2013; Accepted April 8, 2014 Original paper THE PASSAGE OF LOTUS ORNAMENT FROM EGYPTIAN TO THAI A study of origin, metamorphosis, and influence on traditional Thai decorative ornament Suppata WANVIRATIKUL Kyoto Institute of Technology, 1 Hashigami-cho, Matsugasaki, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8585, Japan Abstract: Lotus is believed to be the origin of Thai ornament. The first documented drawing of Thai ornament came with Buddhist missionary from India in 800 AD. Ancient Indian ornament received some of its influence from Greek since 200 BC. Ancient Greek ornament received its influence from Egypt, which is the first civilization to create lotus ornament. Hence, it is valid to assume that Thai ornament should have origin or some of its influence from Egypt. In order to prove this assumption, this research will divine into many parts. This paper is the first part and serves as a foundation part for the entire research, showing the passage, metamorphosis and connotation of Thai ornament from the lotus ornament in Egypt. Before arriving in Thailand, Egyptian lotus had travelled around the world by mean of trade, war, religious, colonization, and politic. Its concept, arrangement and application are largely intact, however, its shape largely altered due to different culture and belief of the land that the ornament has travelled through. Keywords: Lotus; Ornament; Metamorphosis; Influence; Thailand 1. Introduction changing of culture and art. Traditional decorative Through the long history of mankind, the traditional ornament has also changed, nowadays it can be assumed decorative ornament has originally been the symbol of that the derivation has been neglected, the correct meaning identifying and representing the nation. -

Acanthus a Stylized Leaf Pattern Used to Decorate Corinthian Or

Historical and Architectural Elements Represented in the Weld County Court House The Weld County Court House blends a wide variety of historical and architectural elements. Words such as metope, dentil or frieze might only be familiar to those in the architectural field; however, this glossary will assist the rest of us to more fully comprehend the design components used throughout the building and where examples can be found. Without Mr. Bowman’s records, we can only guess at the interpretations of the more interesting symbols used at the entrances of the courtrooms and surrounding each of the clocks in Divisions 3 and 1. A stylized leaf pattern used to decorate Acanthus Corinthian or Composite capitals. They also are used in friezes and modillions and can be found in classical Greek and Roman architecture. Amphora A form of Greek pottery that appears on pediments above doorways. Examples of the use of amphora in the Court House are in Division 1 on the fourth floor. Atrium Inner court of a Roman-style building. A top-lit covered opening rising through all stories of a building. Arcade A series of arches on pillars. In the Middle Ages, the arches were ornamentally applied to walls. Arcades would have housed statues in Roman or Greek buildings. A row of small posts that support the upper Balustrade railing, joined by a handrail, serving as an enclosure for balconies, terraces, etc. Examples in the Court House include the area over the staircase leading to the second floor and surrounding the atria on the third and fourth floors. -

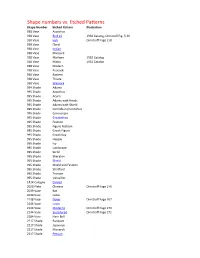

Shape Numbers Vs. Etched Patterns Shape Number Etched Pattern Illustration 938 Vase Acanthus 938 Vase Bird #1 1932 Catalog, Dimitroff Fig

Shape numbers vs. Etched Patterns Shape Number Etched Pattern Illustration 938 Vase Acanthus 938 Vase Bird #1 1932 Catalog, Dimitroff Fig. 5.36 938 Vase Fish Dimitroff Page 278 938 Vase Floral 938 Vase Indian 938 Vase Mansard 938 Vase Marlene 1932 Catalog 938 Vase Matzu 1932 Catalog 938 Vase Modern 938 Vase Peacock 938 Vase Racient 938 Vase Thistle 938 Vase Warwick 954 Shade Adams 995 Shade Acanthus 995 Shade Acorn 995 Shade Adams with Heads 995 Shade Adams with Shield 995 Shade Corinthian (Corinthia) 995 Shade Cornucopia 995 Shade Elizabethan 995 Shade Festoon 995 Shade Figure Festoon 995 Shade Greek Figure 995 Shade Greek Key 995 Shade Hepple 995 Shade Ivy 995 Shade Landscape 995 Shade Scroll 995 Shade Sheraton 995 Shade Shield 995 Shade Shield and Festoon 995 Shade Stratford 995 Shade Trenton 995 Shade Versailles 1414 Cologne Carved 2028 Plate Chinese Dimitroff Page 276 2039 Vase Bat 2039 Vase Lotus 2138 Vase Dover Dimitroff Page 267 2144 Vase Lotus 2144 Vase Moderne Dimitroff Page 270 2144 Vase Sculptured Dimitroff Page 271 2184 Vase Hare Bell 2217 Shade Banquet 2217 Shade Japanese 2217 Shade Monarch 2217 Shade Persian 2217 Shade Raised Leaf 2228 Shade Figure, Dancing 2241 Shade Leaf 2247 Shade Adams 2247 Shade Rennaisance 2249 Shade Rennaisance 2279 Shade Shield and Festoon 2292 Shade Adams Head 2292 Shade Warwick 2311 Shade Adams 2328 Shade Cupid 2328 Shade Festoon with Heads 2328 Shade Greek Figure 2328 Shade Ivy Leaf 2346 Shade Adams Rosette 2346 Shade Figure Rosette 2346 Shade Georgian 2346 Shade Gothic 2346 Shade Kenilworth -

Plant Motifs on Jewish Ossuaries and Sarcophagi in Palestine in the Late Second Temple Period: Their Identification, Sociology and Significance

PLANT MOTIFS ON JEWISH OSSUARIES AND SARCOPHAGI IN PALESTINE IN THE LATE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD: THEIR IDENTIFICATION, SOCIOLOGY AND SIGNIFICANCE A paper submitted to the University of Manchester as part of the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Humanities 2005 by Cynthia M. Crewe ([email protected]) Biblical Studies Melilah 2009/1, p.1 Cynthia M. Crewe CONTENTS Abbreviations ..............................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 Plant Species 1. Phoenix dactylifera (Date palm) ....................................................................................................6 2. Olea europea (Olive) .....................................................................................................................11 3. Lilium candidum (Madonna lily) ................................................................................................17 4. Acanthus sp. ..................................................................................................................................20 5. Pinus halepensis (Aleppo/Jerusalem pine) .................................................................................24 6. Hedera helix (Ivy) .........................................................................................................................26 7. Vitis vinifera -

Study of the Ornamentation of Bhong Mosque for the Survival of Decorative Patterns in Islamic Architecture

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2018) 7, 122–134 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Frontiers of Architectural Research www.keaipublishing.com/foar RESEARCH ARTICLE Study of the ornamentation of Bhong Mosque for the survival of decorative patterns in Islamic architecture Madiha Ahmada,b, Khuram Rashidb,n, Neelum Nazc aDepartment of Architecture, University of Lahore, Pakistan bDepartment of Architectural Engineering and Design, University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan cDepartment of Architecture, University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Received 15 November 2017; received in revised form 15 March 2018; accepted 16 March 2018 KEYWORDS Abstract Bhong Mosque; Islamic architecture is rich in decorative patterns. Mosques were constructed in the past as Decorative patterns; simple buildings for offering prayers five times a day. However, in subsequent periods, Categorization; various features of ornamentation in the form of geometry and arabesque were applied to Geometry; the surfaces of mosques to portray paradise symbolically. This research applied descriptive Arabesque approaches to examine the surviving patterns of the Aga-Khan-awarded Bhong Mosque and categorized these patterns as geometric and arabesque. This categorization was achieved by photography, use of software for patterns, and conducting interviews with local elderly persons in the region. The geometric patterns were simple 6- and 8-point star patterns. Several of the earliest examples of rosette petals exhibited 8- and 10-point star patterns and were categorized by incorporating the geometric style and location of mosques. This research investigated different arabesque categories and inscription types and determined the aesthetic and cultural reasons for their placement on various surfaces. Frescoes had different types of flowers, fruits, and leaves, and a few of them belonged to the local region. -

Corinth, 1987: South of Temple E and East of the Theater

CORINTH, 1987: SOUTH OF TEMPLE E AND EAST OF THE THEATER (PLATES 33-44) ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens were conductedin 1987 at Ancient Corinth south of Temple E and east of the Theater (Fig. 1). In both areas work was a continuationof the activitiesof 1986.1 AREA OF THE DECUMANUS SOUTH OF TEMPLE E ROMAN LEVELS (Fig. 1; Pls. 33-37:a) The area that now lies excavated south of Temple E is, at a maximum, 25 m. north-south by 13.25 m. east-west. The earliest architecturalfeature exposed in this set of trenches is a paved east-west road, identified in the 1986 excavation report as the Roman decumanus south of Temple E (P1. 33). This year more of that street has been uncovered, with a length of 13.25 m. of paving now cleared, along with a sidewalk on either side. The street is badly damaged in two areas, the result of Late Roman activity conducted in I The Greek Government,especially the Greek ArchaeologicalService, has again in 1987 made it possible for the American School to continue its work at Corinth. Without the cooperationof I. Tzedakis, the Director of the Greek ArchaeologicalService, Mrs. P. Pachyianni, Ephor of Antiquities of the Argolid and Corinthia, and Mrs. Z. Aslamantzidou, epimeletria for the Corinthia, the 1987 season would have been impossible. Thanks are also due to the Director of the American School of Classical Studies, ProfessorS. G. Miller. The field staff of the regular excavationseason includedMisses A. A. Ajootian,G. L. Hoffman, and J. -

Coverpage Final

Symbols and Objects on the Sealings from Kedesh A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Paul Lesperance IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Professor Andrea Berlin August 2010 © Paul Lesperance, 2010 Acknowledgements I have benefitted greatly from the aid and support of many people and organizations during the writing of this dissertation. I would especially like to thank my advisor, Professor Andrea Berlin, for all her help and advice at all stages of the production process as well as for suggesting the topic to me in the first place. I would also like to thank all the members of my dissertation committee (Professor Susan Herbert of the University of Michigan, as well as Professors Philip Sellew and Nita Krevans of the University of Minnesota) for all their help and support. During the writing process, I benefitted greatly from a George A. Barton fellowship to the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem in the fall of 2009. I would like to thank the fellowship committee for giving me such a wonderful and productive opportunity that helped me greatly in this endeavour as well as the staff of the Albright for their aid and support. I would also like to thank both Dr. Donald Ariel of the Israel Antiquities Authority for his aid in getting access to the material and his valuable advice in ways of looking at it and Peter Stone of the University of Cincinnati whose discussions on his work on the pottery from Kedesh helped to illuminate various curious aspects of my own.