Representations of Samaritans in Late Antique Jewish And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Box List of Moses Gaster's Working Papers at the John Rylands

Box list of Moses Gaster’s working papers at the John Rylands University Library, Manchester Maria Haralambakis, 2012 This box list provides a guide to a specific segment of the wide ranging Gaster collection at The John Rylands Library, part of the University of Manchester, namely the contents of thirteen boxes of ‘Gaster Papers’. It is intended to help researchers to search for items of interest in this extensive but largely untapped collection. The box list is a work in progress and descriptions of the first six boxes are at present more detailed than those of boxes seven to thirteen. Most of the work in preparation for this box list has been undertaken in the context of a postdoctoral research fellowship funded by the Rothschild Foundation (Hanadiv) Europe at the Centre for Jewish Studies in the University of Manchester (September 2011– August 2012). Biographical history Moses Gaster was born in Bucharest (Romania) to a privileged Jewish family in 1856. His mother's name was Phina Judith Rubinstein. His father, Abraham Emanuel Gaster (d. 1926), was the commercial attaché of the Dutch consulate. Gaster went to Germany in 1873 to pursue philological studies at the University of Breslau, which he combined with studying for his Rabbinic degree at the Rabbinic Seminary of Breslau. He defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Leipzig. After his studies, in 1881, he returned to Romania and lectured in Romanian language and literature at the University of Bucharest. He also officiated as an inspector of secondary schools (from 1883) and an examiner of teachers (from 1884). -

Ra'anan Shaul Boustan

RA‘ANAN SHAUL BOUSTAN Program in Judaic Studies Princeton University 201 Scheide Caldwell House Princeton, NJ 08544 [email protected] ______________________________________________________ EDUCATION 2004 Ph.D., Religion, Princeton University (Ancient Mediterranean Religions) 2000 M.A., Religion, Princeton University (Ancient Mediterranean Religions) 1995 Vrij Doctoraal Letteren, University of Amsterdam (Classics and Religion) 1994 A.B., Brown University (Classics) PRIMARY ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2017– Research Scholar (with continuing appointment), Program in Judaic Studies, Princeton University 2010–18 Associate Professor, History, University of California at Los Angeles 2006–10 Assistant Professor, History and NELC, University of California at Los Angeles 2004–6 Assistant Professor, Classical & Near Eastern Studies, University of Minnesota VISITING ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2015 Lecturer, Summer School at the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies, Jerusalem (July 5–9) 2011–12 Donald D. Harrington Faculty Fellow, Department of Religious Studies, UT Austin 2010 Lecturer, Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest (March) ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS 2009–12 Director, UCLA Center for the Study of Religion 2009–12 Chair, UCLA Study of Religion Undergraduate Program EDITORIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Editor-in-Chief, Studies in Late Antiquity: A Journal, 2021– Editor-in-Chief, Jewish Studies Quarterly, 2016– Editorial Board, Book series: Jews & Judaism in Roman Antiquity (Academic Studies Press), 2016– Associate Editor, Book series: Archaeology, Culture & History of the Ancient Near East (Routledge), 2015– Associate Editor, Book series: Martyrdom and Literature (Harrassowitz Verlag), 2015– Editorial Board, Journal of Religion and Violence, 2017– Editorial Board, Journal of the Jesus Movement in its Jewish Setting, 2014– Associate Editor, Studies in Late Antiquity: A Journal, 2016–2020 Editorial Committee, University of California Press, 2014–2017 Editorial Board, Perspectives: The Magazine of the Association for Jewish Studies, 2004–6 I. -

Pythagorean, Predecessor, and Hebrew: Philo of Alexandria and the Construction of Jewishness in Early Christian Writings

Pythagorean, Predecessor, and Hebrew: Philo of Alexandria and the Construction of Jewishness in Early Christian Writings Jennifer Otto Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University, Montreal March, 2014 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Jennifer Otto, 2014 ii Table of Contents Abstracts v Acknowledgements vii Abbreviations viii Introduction 1 Method, Aims and Scope of the Thesis 10 Christians and Jews among the nations 12 Philo and the Wisdom of the Greeks 16 Christianity as Philosophy 19 Moving Forward 24 Part I Chapter 1: Philo in Modern Scholarship 25 Introducing Philo 25 Philo the Jew in modern research 27 Conclusions 48 Chapter 2: Sects and Texts: The Setting of the Christian Encounter with Philo 54 The Earliest Alexandrian Christians 55 The Trajanic Revolt 60 The “Catechetical School” of Alexandria— A Continuous 63 Jewish-Christian Institution? An Alternative Hypothesis: Reading Philo in the Philosophical Schools 65 Conclusions 70 Part II Chapter 3: The Pythagorean: Clement’s Philo 72 1. Introducing Clement 73 1.1 Clement’s Life 73 1.2 Clement’s Corpus 75 1.3 Clement’s Teaching 78 2. Israel, Hebrews, and Jews in Clement’s Writings 80 2.1 Israel 81 2.2 Hebrews 82 2.3 Jews 83 3. Clement’s Reception of Philo: Literature Review 88 4. Clement’s Testimonia to Philo 97 4.1 Situating the Philonic Borrowings in the context of Stromateis 1 97 4.2 Stromateis 1.5.31 102 4.3 Stromateis 1.15.72 106 4.4 Stromateis 1.23.153 109 iii 4.5 Situating the Philonic Borrowings in the context of Stromateis 2 111 4.6 Stromateis 2.19.100 113 5. -

JSP News Fall 08

@PENN T HE J EWISH S TUDIES N EWSLETTER Fall 2009 Jewish Studies at the University of Pennsylvania Penn, through its Jewish Studies Program and the Herbert distinguished scholars to Penn as fellows to pursue scholarly D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, offers one of the research on selected themes. These fellows are selected from the most comprehensive programs in Jewish Studies in America. finest and most prominent Judaic scholars in the world. Every The Jewish Studies Program (JSP) is an interdisciplinary year several Katz Center fellows teach courses at Penn, and both academic group with twenty-one faculty members from eight graduate students and University faculty participate in the Katz departments that coordinates all courses relating to Jewish Center’s weekly seminars. The Katz Center is also home to one Studies in the university, as well as undergraduate majors and of America’s greatest research libraries in Judaica and Hebraica minors and graduate programs in different departments. JSP and includes a Genizah collection, many manuscripts, and early also sponsors many events, including two endowed lectureships printings. Together the Jewish Studies Program and the Herbert and the Kutchin Faculty Seminars. The Herbert D. Katz Center D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies make Penn one of for Advanced Judaic Studies (Katz Center) is a post-doctoral the most rich and exciting communities for Jewish scholarship research institute that annually brings eighteen to twenty-five and intellectual life in the world. Loading of wheat in the Emek [Jezreel Valley], 1936. The Jewish Agency included this extraordinary image in an album given to General Waulkhope on his departure at the end of his term as high commissioner for Palestine (Feb. -

Ra'anan Shaul Boustan

RA‘ANAN SHAUL BOUSTAN Program in Judaic Studies Princeton University 201 Scheide Caldwell House Princeton, NJ 08544 [email protected] ______________________________________________________ EDUCATION 2004 Ph.D., Religion, Princeton University (Ancient Mediterranean Religions) 2000 M.A., Religion, Princeton University (Ancient Mediterranean Religions) 1995 Vrij Doctoraal Letteren, University of Amsterdam (Classics and Religion) 1994 A.B., Brown University (Classics) PRIMARY ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2017– Research Scholar (with continuing appointment), Program in Judaic Studies, Princeton University 2010–18 Associate Professor, History, University of California at Los Angeles 2006–10 Assistant Professor, History and NELC, University of California at Los Angeles 2004–6 Assistant Professor, Classical & Near Eastern Studies, University of Minnesota VISITING ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2015 Lecturer, Summer School at the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies, Jerusalem (July 5–9) 2011–12 Donald D. Harrington Faculty Fellow, Department of Religious Studies, UT Austin 2010 Lecturer, Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest (March) ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS 2009–12 Director, UCLA Center for the Study of Religion 2009–12 Chair, UCLA Study of Religion Undergraduate Program EDITORIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Co-editor, Jewish Studies Quarterly, 2016– Associate Editor, Studies in Late Antiquity: A Journal, 2016– Editorial Board, Book series: Jews & Judaism in Roman Antiquity (Academic Studies Press), 2016– Associate Editor, Book series: Archaeology, Culture & History of the Ancient Near East (Routledge), 2015– Associate Editor, Book series: Martyrdom and Literature (Harrassowitz Verlag), 2015– Editorial Board, Journal of Religion and Violence, 2017– Editorial Board, Journal of the Jesus Movement in its Jewish Setting, 2014– Editorial Committee, University of California Press, 2014–2017 Editorial Board, Perspectives: The Magazine of the Association for Jewish Studies, 2004–6 I. -

MATTHEW CHALMERS Department of Religious Studies, Crowe Hall 4-145 1860 Campus Drive Evanston, IL 60208 267-439-7605 | [email protected]

MATTHEW CHALMERS Department of Religious Studies, Crowe Hall 4-145 1860 Campus Drive Evanston, IL 60208 267-439-7605 | [email protected] Note: due to COVID-19, I am currently teaching remotely. All correspondence should be sent to: 2 Estill Street, Apt. G; Lexington, VA 24450 EMPLOYMENT VISITING ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES | 2020-2022 | NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY · Teaching: Late Antiquity, History of Christianity, Materiality and Religion VISITING ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGION | 2019-2020 | WASHINGTON AND LEE UNIVERSITY · Teaching: Jewish Studies, Ancient Near East, Hebrew Bible, Early Christianity EDUCATION PHD | 2013-2019 | UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA · Department of Religious Studies · Dissertation: Representations of Samaritans in Late Antique Christian and Jewish Texts MPHIL | 2011-2013 | UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD · Theology (Patristics): Clement of Alexandria, Egyptian Christianity, Greco-Roman philosophy BA | 2008-2011 | UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD · Philosophy and Theology RESEARCH LANGUAGES Ancient: Greek, Latin, Coptic, Syriac, Hebrew, Aramaic Modern: French, German, Hebrew 1 PUBLICATIONS IN PROGRESS [Manuscript in preparation] The Samaritan Other: A New History of Religious Identity in Late Antiquity [Under Review] Samaritans, Biblical Studies, and Ancient Judaism: Recent Trends. [Forthcoming 2022, Harvard Theological Review] Past Paul’s Jewishness: The Benjaminite Paul in Epiphanius of Cyprus. [Forthcoming 2021] Theme-issue in Studies in Late Antiquity: Theorizing Late Antique Disaster in Past and Present: Individual and Rhetorical Responses. [Forthcoming 2021, Studies in Late Antiquity] The Rise and Fall of Peripheral Peoples? Samaritans, Muslims, and Late Antique Discourses of Disaster. [Forthcoming 2021, in The Samaritans: Tales of a Biblical People, ed. Steven Fine, pub. Brill] Jewish Knowledge, Christian Scholars, and the European ‘Discovery’ of Samaritans. -

Envisioning Judaism Studies in Honor of Peter

Envisioning Judaism Studies in Honor of Peter Schäfer on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday Vol. 1 Envisioning Judaism Studies in Honor of Peter Schäfer on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday Edited by Raʿanan S. Boustan, Klaus Herrmann, Reimund Leicht, Annette Yoshiko Reed, and Giuseppe Veltri with the collaboration of Alex Ramos Volume 1 Mohr Siebeck ISBN 978-3-16-152227-7 Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http: //dnb.dnb.de. © 2013 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen, printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübin- gen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgements The present volume is the product of collaboration by former students of Peter Schäfer in the United States, Israel, and Germany. The five editors each oversaw a set of articles – Raʿanan S. Boustan on ancient Jewish his- tory, Klaus Herrmann on rabbinic history and literature, Giuseppe Veltri on Hekhalot and Jewish mysticism, Annette Yoshiko Reed on Jews and Chris- tians, and Reimund Leicht on medieval and early modern Judaism. During the early phases of the project, Lisa Cleath of the University of California at Los Angeles and Rachel Levine and Brad King of the University of Texas at Austin aided with editorial work. -

Feraru Ionel, Son Vrai Nom Est Finkelstein Izi

201 [13 martie 1952] Dates biographiques concernant le communiste Ionel Feraru 1. Nom et prénom: Feraru Ionel, son vrai nom est Finkelstein Izi. 2. Dernière fonction: Chef du Service de Contrôle Economique près la Milice Rayonnale de Galaþi. 3. Grade: Lieutenant de Milice. Il n’a pas fait le service militaire. 4. Age: 30 ans environ. 5. Taille: 1,60 m environ. 6. Cheveux: Noirs avec raie sur on côté. 7. 7. Yeux: Noirs. 8. Signes particuliers: Gras, avec un visage pointu orné d’une moustache. 9. Etat civil: Marié. Originaire de Galaþi où il a habité 26, rue Domneascã. 10. Etudes: Il a suivi l’école primaire et puis 4 classes du lycée juif. 11. Domicile: Habite à Galaþi, au 9 rue Instrucþiei. 12. Appartenance politique: Membre de l’UTM d’abord puis il devient membre du parti vers 1950. 13. Détails supplémentaires: Son père a étè un commerçant aisé à Galaþi ayant un magasin au 26, rue Domneascã. Il a changé de nom vers 1948. Il a étè 4 ans ab- sent de Galaþi. Avant d’être nommé chef du service économique, il était agent auprés de ce service. Il est extrémement brutal avec tous ceux qui lui tombent dans les mains; il les injurie et les frappe même. Il poursuit et brutalise notamment la population juive qui ressente une véritable terreur devant lui. Il ménait une activi- té propagandistique et faisait tout son possible afin d’empêcher les juifs d’émigrer en Israel. Pendant qu’il était agent de contrôle, il faisait partie de l’équipe des deux autres communistes: Kessler et Mãglãdeanu à qui il manque une oreille. -

The Subversive Action of the Urban Camp Irit Katz Feigis

Resourceful Cities Berlin, 29-31 August 2013 From Exclusion to Co-operation – The Subversive Action of the Urban Camp Irit Katz Feigis Paper presented at the International RC21 Conference 2013 Session 24.1 Encapsulating, including, excluding: urban camps from a global perspective Draft version. Please do not circulate and do not cite without the permission of the author. PhD Candidate The Department of Architecture University of Cambridge 1-5 Scroope Terrace, Cambridge, CB2 1PX, UK [email protected] 1 Abstract1 Since the early decades of the 20th century camps have been used as an instrument in order to suspend, control and administer land and population in Israel/Palestine. In a state of emergency, when the normal law is suspended, the camp is a quick translation of a political agenda or a humanitarian crisis into an ad-hoc act of construction where civic life and military action interacts. Within a specific context, the paper will analyse two neighbouring settlements in the southern Negev desert; Yerucham - created in the 1950s by the Israeli government as a Jewish immigrant absorption camp and eventually turned into a minor development town, and the neighbouring Rachme, an ‘unrecognised village’ which was created in the 1960s as an informal camp by the indigenous Bedouin population and is now struggling for government recognition. The paper will examine the relations between Yerucham and Rachme, which in opposition to the Israeli policy of ethnic segregation manage to act together in order to improve their own difficult reality. The paper will argue that camps have become a site for the emergence of new subjectivities which use legal, spatial and political actions to resist the oppressive power of the state, and that the abandonment and suspension of these two populations has expedited their resourceful co- operation in challenging the modes of traditional governance. -

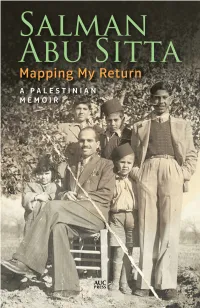

Mapping My Return

Mapping My Return Mapping My Return A Palestinian Memoir SALMAN ABU SITTA The American University in Cairo Press Cairo New York This edition published in 2016 by The American University in Cairo Press 113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt 420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 www.aucpress.com Copyright © 2016 by Salman Abu Sitta All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Exclusive distribution outside Egypt and North America by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd., 6 Salem Road, London, W2 4BU Dar el Kutub No. 26166/14 ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abu Sitta, Salman Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir / Salman Abu Sitta.—Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2016 p. cm ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 1. Beersheba (Palestine)—History—1914–1948 956.9405 1 2 3 4 5 20 19 18 17 16 Designed by Amy Sidhom Printed in the United States of America To my parents, Sheikh Hussein and Nasra, the first generation to die in exile To my daughters, Maysoun and Rania, the first generation to be born in exile Contents Preface ix 1. The Source (al-Ma‘in) 1 2. Seeds of Knowledge 13 3. The Talk of the Hearth 23 4. Europe Returns to the Holy Land 35 5. The Conquest 61 6. The Rupture 73 7. The Carnage 83 8. -

Course Catalog | Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies 1

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies Table of Contents Ancient Jewish History .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Medieval Jewish History ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Modern Jewish History ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Bible .................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Jewish Philosophy ............................................................................................................................................... 20 Talmud ................................................................................................................................................................ 24 Course Catalog | Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies 1 Ancient Jewish History JHI 6221 (Hebraism & Hellenism: Greco-Roman Culture & the Rabbis) also counts toward the Talmudic Studies concentration. JHI 6241 (Second Temple Period Aramaic) also counts toward the Bible concentration. JHI 6243 (Samaritans and Jews: From the Bible to Modern Israel) and 6255 (Jewish Art and Visual Culture) also count toward the Medieval and Modern History concentrations. JHI 6461 (Historians on Chazal: -

Unreached of the Day SEPT–OCT 2021

Unreached of the Day SEPT–OCT 2021 Note: Scripture references are from the English Standard But he answered, It is written, Man shall Matthew Version (ESV). Images in this guide (marked with an asterisk *) not live by bread alone, but by every word 4:4 come from the International Mission Board (IMB). We thank the that comes from the mouth of God. IMB for their exquisite images, taken by workers in the field. • Pray for today’s people group to learn and understand that the Bible comes from the mouth SEPTEMBER and mind of the one, true God. • Pray for the Lord to improve their lives physically, economically and spiritually. Pray for the Lord to protect them from the spirit world and for them to understand the power of the Lord. 3 South Ucayali Asheninka in Peru The South Ucayali Asheninka in Peru have suffered greatly at the hands of outsiders and terrorist groups. They are subsistence farmers and work mostly in the morning and rest during the heat of the afternoon. Often the men go hunting and fishing in the evenings. They have an animistic worldview, and they use shamans to look for the causes of life problems and appease wicked spirits. 1 Malayo in Colombia The people dwelling in darkness have seen Matthew a great light, and for those dwelling in the Who are these men, all dressed in white with long black 4:16 region and shadow of death, on them a hair? They are the Malayo, also known as Wiwa people, light has dawned. who live in the valleys of the Sierra Nevada Mountains • Pray for this people group to see the light of Jesus of Colombia.