Mapping My Return

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2010 - 2012 Volume VII

BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights is an independent, community-based non- This edition of the Survey of Palestinian Survey of Palestinian Refugees and profit organization mandated to defend Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons BADIL Internally Displaced Persons 2010-2012 and promote the rights of Palestinian (Volume VII) focuses on Palestinian Vol VII 2010-2012 refugees and Internally Displaced Persons Survey of refugees and IDPs. Our vision, mission, 124 Pages, 30 c.m. (IDPs) in the period between 2010 and ISSN: 1728-1679 programs and relationships are defined 2012. Statistical data and estimates of the by our Palestinian identity and the size of this population have been updated Palestinian Refugees principles of international law, in in accordance with figures as of the end Editor: Nidal al-Azza particular international human rights of 2011. This edition includes for the first law. We seek to advance the individual time an opinion poll surveying Palestinian Editorial Team: Amjad Alqasis, Simon and collective rights of the Palestinian refugees regarding specific humanitarian and Randles, Manar Makhoul, Thayer Hastings, services they receive in the refugee Noura Erakat people on this basis. camps. Demographic Statistics: Mustafa Khawaja BADIL Resource Center was established The need to overview and contextualize in January 1998. BADIL is registered Palestinian refugees and (IDPs) - 64 Internally Displaced Persons Layout & Design: Atallah Salem with the Palestinan Authority and years since the Palestinian Nakba Printing: Al-Ayyam Printing, Press, (Catastrophe) and 45 years since Israel’s legally owned by the refugee community Publishing and Distribution Conmpany represented by a General Assembly belligerent occupation of the West Bank, including eastern Jerusalem, and the 2010 - 2012 composed of activists in Palestinian Gaza Strip - is derived from the necessity national institutions and refugee to set the foundations for a human rights- community organizations. -

Abuses Against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces WATCH

Occupied Palestinian Territories HUMAN No News is Good News RIGHTS Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces WATCH No News is Good News Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-759-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org April 2011 ISBN: 1-56432-759-0 No News is Good News Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 3 West Bank ....................................................................................................................... 5 Reports of Increased Harassment ............................................................................. 6 The Role of PA Security Forces ................................................................................... 7 Gaza ............................................................................................................................. -

Conflict Management and Mitigation Program

CONFLICT MANAGEMENT AND MITIGATION PROGRAM USAID West Bank/Gaza and the U.S. Embassy in Israel jointly invest in Conflict Management and Mitigation (CMM) grants, which support Israelis and Palestinians, as well as Jewish and Arab citizens of Israel, working on issues of common concern. The CMM program is part of a worldwide effort to bring together individuals of different backgrounds from areas of conflict in people-to-people reconciliation activities. These activities provide opportunities to address issues, reconcile differences, and promote greater understanding and mutual trust by working on common goals such as economic development, environment, health, education, sports, music, and information technology. Since the program’s start in 2004, USAID and the U.S. Embassy have invested in 136 CMM grants. GRANTS MANAGED BY USAID The Abraham Fund Initiatives (2018-2022; $986,000): The Shared Learning project bridges the cultural divide between 40 pairs of Jewish and Arab schools through language exchange studies. The project will provide joint learning opportunities for 200 Jewish and Arab educators and over 2,000 students, promoting positive and constructive interactions and demonstrating that cooperation leads to greater trust and understanding. Akko Center for Arts and Technology (2018-2021; $1,322,000): The Full STEAM Ahead project engages over 900 Jewish and Arab youth from underserved communities in science, technology, engineering, arts, and math activities to build their skills and knowledge to better compete in a 21st century job market. By working together in a bicultural and bilingual environment to create and innovate, students will develop an inclusive view of one KEIDAR NIR another and strengthen Jewish-Arab relations in Israel. -

29/06/2020 Signatories List for “Appeal from Palestine to the Peoples and States of the World”

29/06/2020 Signatories List for “Appeal from Palestine to the Peoples and States of the World” Name Current/ Previous Occupation 1. ‘Ahd Bassem Tamimi Civil Society Activist –Ramallah 2. Abbas Zaki Member of the Central Committee of Fatah—Ramallah 3. Abd El-Qader Husseini Chairman of Faisal Husseini Foundation— Jerusalem 4. Abdallah Abdallah Former PLC Member—Ramallah 5. Abdallah Abu Alhnoud Member of the Fatah Advisory Council— Gaza 6. Abdallah Abu Hamad President of Taraji Wadi Al-Nes Sports Club—Bethlehem 7. Abdallah Bashir Director of Jordan Hospital, Surgeon – Amman 8. Abdallah Hijazi President of the Civil Retired Assembly, Former Ambassador—Ramallah 9. Abdallah Kamel Coordinator of the Palestinian Cultural Center—Beirut 10. Abdallah Sabri President of the Palestinian General Union of Charitable Societies –Jerusalem 11. Abdallah Taqash Doctor—Germany 12. Abdallah Theeb Director of the Administrative Office of the Federation of Palestinian Trade Unions— North Lebanon, Beirut 13. Abdallah Yousif Alsha’rawi President of the Palestinian Motors Sport & Motorcycle & Bicycles Federation— Ramallah 14. Abdel Fatah Alqalqili Retired Ambassador and Writer—Ramallah 15. Abdel Halim Attiya President of Al-Thahirya Youth Club— Hebron 16. Abdel Jalil Zreiqat President of Tafouh Youth Sports Club— Hebron 17. Abdel Karim Abu Khashan University Lecturer, Birzeit University— Ramallah 18. Abdel Majid Hijeh Secretary-General of the Olympic Committee—Ramallah 19. Abdel Majid Sweilem University Lecturer and Journalist— Ramallah 20. Abdel Qader Hasan Abdallah Secretary-General of the Palestine Workers Kabouli Union—Lebanon, Alkharoub Region 21. Abdel Qader Ibrahim Hamad Academic and Writer—Gaza 22. Abdel Rahim Awad Secretary of the People’s Committee in the Beqaa—Beirut 1 23. -

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: the Most Important Events Yasser

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: The Most Important Events Yasser Arafat Foundation 1 Early 20th Century - The total population of Palestine is estimated at 600,000, including approximately 36,000 of the Jewish faith, most of whom immigrated to Palestine for purely religious reasons, the remainder Muslims and Christians, all living and praying side by side. 1901 - The Zionist Organization (later called the World Zionist Organization [WZO]) founded during the First Zionist Congress held in Basel Switzerland in 1897, establishes the “Jewish National Fund” for the purpose of purchasing land in Palestine. 1902 - Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II agrees to receives Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement and, despite Herzl’s offer to pay off the debt of the Empire, decisively rejects the idea of Zionist settlement in Palestine. - A majority of the delegates at The Fifth Zionist Congress view with favor the British offer to allocate part of the lands of Uganda for the settlement of Jews. However, the offer was rejected the following year. 2 1904 - A wave of Jewish immigrants, mainly from Russia and Poland, begins to arrive in Palestine, settling in agricultural areas. 1909 Jewish immigrants establish the city of “Tel Aviv” on the outskirts of Jaffa. 1914 - The First World War begins. - - The Jewish population in Palestine grows to 59,000, of a total population of 657,000. 1915- 1916 - In correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, and Sharif Hussein of Mecca, wherein Hussein demands the “independence of the Arab States”, specifying the boundaries of the territories within the Ottoman rule at the time, which clearly includes Palestine. -

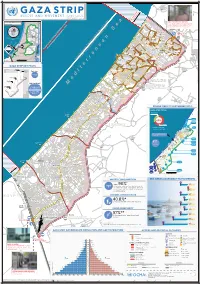

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

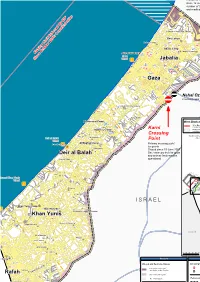

Gaza Strip Closure Map , December 2007

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Access and Closure - Gaza Strip December 2007 s rd t: o i t c im n N c L e o Erez A . m F g m t i lo n . i s s i n m h Crossing Point h t: in O s 0 m i s g i 2 o le F im i A Primary crossing for people (workers C L m re i l a and traders) and humanitarian personnel in g a rt in c Closed for Palestinian workers e h ti s u since 12 March 2006 B i a 2 F Closed for Palestinians 0 n 0 2 since 12 June 2007 except for a limited 2 1 number of traders, humanitarian workers and medical cases s F le D i I m y l B a d ic e t c u r a Al Qaraya al Badawiya al Maslakh ¯p fo n P Ç 6 n : ¬ E 6 it 0 Beit Lahiya 0 im 2 P L r Madinat al 'Awda e P ¯p "p ¯p "p g b Beit Hanoun in o ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p h t Jabalia Camp ¯p ¯p ¯p P ¯p s c p ¯p ¯p i p"p ¯¯p "pP 'Izbat Beit HanounP F O Ash Shati' Camp ¯p " ¯p e "p "p ¯p ¯p c Gaza ¯Pp ¯p "p n p i t ¯ Wharf S Jabalia S t !x id ¯p S h s a a "p m R ¯p¯p¯p ¯p a l- ¯p p r A ¯p ¯ a "p K "p ¯p l- ¯p "p E ¯p"p ¯p¯p"p ¯p¯p ¯p Gaza ¯p ¯p ¯p ¯p t S ¯p a m ¯p¯p ¯p ra a K l- Ç A ¬ Nahal Oz ¯p ¬Ç Crossing point for solid and liquid fuels p t ¯ t S fa ¯p Al Mughraqa (Abu Middein) ra P r A e as Y Juhor ad Dik ¯pP ¯p LEBANON An Nuseirat Camp ¯p ¯p West Bank and Gaza Strip P¯p ¯p ¯p West Bank Barrier (constructed and planned) ¯p ¯p ¯p Al Bureij Camp¯p ¯p Karni Areas inaccessible to Palestinians or subject to restrictions ¯p¯pP¯p Crossing `Akko !P MEDITERRANEAN Az Zawayda !P Deir al Balah ¯p P Point SEA Haifa Tiberias !P Wharf Nazareth !P ¯p Al Maghazi Camp¯p¯p Deir al Balah Camp Primary -

Memory Trace Fazal Sheikh

MEMORY TRACE FAZAL SHEIKH 2 3 Front and back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°50 41”N / 35°13 47”E Israeli side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of Neve Yaakov and Beit Ḥanīna. Just beyond the wall lies the neighborhood of al-Ram, now severed from East Jerusalem. Inside front and inside back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°49 10”N / 35°15 59”E Palestinian side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of the Palestinian town of ʿAnata. The Israeli settlement of Pisgat Ze’ev lies beyond in East Jerusalem. This publication takes its point of departure from Fazal Sheikh’s Memory Trace, the first of his three-volume photographic proj- ect on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Published in the spring of 2015, The Erasure Trilogy is divided into three separate vol- umes—Memory Trace, Desert Bloom, and Independence/Nakba. The project seeks to explore the legacies of the Arab–Israeli War of 1948, which resulted in the dispossession and displacement of three quarters of the Palestinian population, in the establishment of the State of Israel, and in the reconfiguration of territorial borders across the region. Elements of these volumes have been exhibited at the Slought Foundation in Philadelphia, Storefront for Art and Architecture, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York, and will now be presented at the Al-Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art in East Jerusalem, and the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah. In addition, historical documents and materials related to the history of Al-’Araqīb, a Bedouin village that has been destroyed and rebuilt more than one hundred times in the ongoing “battle over the Negev,” first presented at the Slought Foundation, will be shown at Al-Ma’mal. -

The Tunnels in Gaza February 2015 the Tunnels in Gaza Testimony Before the UN Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict Dr

Dr. Eado Hecht 1 The Tunnels in Gaza February 2015 The Tunnels in Gaza Testimony before the UN Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict Dr. Eado Hecht The list of questions is a bit repetitive so I have decided to answer not directly to each question but in a comprehensive topical manner. After that I will answer specifically a few of the questions that deserve special emphasis. At the end of the text is an appendix of photographs, diagrams and maps. Sources of Information 1. Access to information on the tunnels is limited. 2. I am an independent academic researcher and I do not have access to information that is not in the public domain. All the information is based on what I have gleaned from unclassified sources that have appeared in the public media over the years – listing them is impossible. 3. The accurate details of the exact location and layout of all the tunnels are known only by the Hamas and partially by Israeli intelligence services and the Israeli commanders who fought in Gaza last summer. 4. Hamas, in order not to reveal its secrets to the Israelis, has not released almost any information on the tunnels themselves except in the form of psychological warfare intended to terrorize Israeli civilians or eulogize its "victory" for the Palestinians: the messages being – the Israelis did not get all the tunnels and we are digging more and see how sophisticated our tunnel- digging operation is. These are carefully sanitized so as not to reveal information on locations or numbers. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

David Abrams, Attorney at Law August 21, 2019 To

David Abrams, Attorney at Law P.O. Box 3353 Church Street Station, New York NY 10008 Tel. 212-897-5821 Fax 212-897-5811 August 21, 2019 To: Internal Revenue Service (by FedEx) Whistleblower Office - ICE 1973 N. Rulon White Blvd. M/S 4110 Ogden, UT 84404 Re: Whistleblower Complaint Against New Israel Fund Dear Sir / Madam: I am the whistleblower in connection with the above-referenced Complaint. Enclosed please find a completed IRS Form 211.. Further, I am respectfully submitting this memorandum to elaborate on the factual and legal aspects of the enclosed IRS whistleblower complaint. In addition, I am enclosing a CD which contains the full, unannotated versions of the documents attached as Exhibits hereto. 1. Who is New Israel Fund? New Israel Fund (“NIF”) is a District of Columbia non-profit 501(c)(3) corporation with its principal place of business in the State of New York, county of New York. NIF financially supports many companies that work to undermine the state of Israel. As set forth in more detail below, NIF has crossed the line from permissible advocacy to unlawful "electioneering." Put another way, NIF is violating the tax codes by attempting to influence the outcome of elections. As stated on its own web site, NIF works on its “concerted campaign to equip Israel’s pro-democracy and progressive forces with the tools to fight Israel’s regressive right-and win.” As set forth in more detail below, NIF's activities are flagrant and unlawful electioneering in violation of the tax code. 2. Who is the Whistleblower? I am a New York attorney and political activist who regularly engages in pro- Israel litigation in state and federal Court. -

Full Translation Date Completed: 15 NOV 2007

Document Number: NMEC-2007-659296 Type of Translation: Full Translation Date Completed: 15 NOV 2007 This is detailed personal information on the following foreign fighter. [Page 1 of 1] {Personal information for foreign fighters} The Islamic State of Iraq Name: Muhammad Anwar Rafiia’a Yahiya Alias: Abu Abd Al kabeer Address: Dernah- Libya Telephone number: None Birth Date: 3/10/1990 Arrival Date: 22nd of Rabi al-thani Contribution: 2000 Syrian Lira an $12 Valuables: // Coordinator: Bashar Where do you know the coordinator from? I know him well How did you arrive to Syria? Libya/ Egypt/ Syria Stages of arrival to Iraq: Syria/ Iraq Who are the people you met in Syria? Abu Abbas What are their descriptions? // How did the coordinator treat you in Syria? Good How much money did you bring with you? 700 Libyan Dinars How much money did they take from you in Syria? // How did they take the money? // Do you know any mujahdeen supporters? What are their phone numbers? // What is the extent of your relationship with them? // Work: Martyrdom Occupation at home: Student Experience: Administrator Signature Day …….. Date …….. [End of Translation] Document # NMEC-2007-657656 Full Translation October 10, 2007 {Personal information for foreign fighters} Name: Ja'far Abu-Zanjah Alias: Abu-'Abbas Address: the capital of Algeria Telephone: 0021321263630 home / 0021371614213 Birth Date: 1981 Arrival Date: Contribution: / Valuables: passport Coordinator: Samir Where do you know the coordinator from: his friend How did you arrive to Syria? By plane Stages of