Chapter 4 the Current Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMS112 1978-1979 Lowres Web

--~--------~--------------------------------------------~~~~----------~-------------- - ~------------------------------ COVER: Paul Webber, technical officer in the Herpetology department searchers for reptiles and amphibians on a field trip for the Colo River Survey. Photo: John Fields!The Australian Museum. REPORT of THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM TRUST for the YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE , 1979 ST GOVERNMENT PRINTER, NEW SOUTH WALES-1980 D. WE ' G 70708K-1 CONTENTS Page Page Acknowledgements 4 Department of Palaeontology 36 The Australian Museum Trust 5 Department of Terrestrial Invertebrate Ecology 38 Lizard Island Research Station 5 Department of Vertebrate Ecology 38 Research Associates 6 Camden Haven Wildlife Refuge Study 39 Associates 6 Functional Anatomy Unit.. 40 National Photographic Index of Australian Director's Research Laboratory 40 Wildlife . 7 Materials Conservation Section 41 The Australian Museum Society 7 Education Section .. 47 Letter to the Premier 9 Exhibitions Department 52 Library 54 SCIENTIFIC DEPARTMENTS Photographic and Visual Aid Section 54 Department of Anthropology 13 PublicityJ Pu bl ications 55 Department of Arachnology 18 National Photographic Index of Australian Colo River Survey .. 19 Wildlife . 57 Lizard Island Research Station 59 Department of Entomology 20 The Australian Museum Society 61 Department of Herpetology 23 Appendix 1- Staff .. 62 Department of Ichthyology 24 Appendix 2-Donations 65 Department of Malacology 25 Appendix 3-Acknowledgements of Co- Department of Mammalogy 27 operation. 67 Department of Marine -

Captain Bligh

www.goglobetrotting.com THE MAGAZINE FOR WORLD TRAVELLERS - SPRING/SUMMER 2014 CANADIAN EDITION - No. 20 CONTENTS Iceland-Awesome Destination. 3 New Faces of Goway. 4 Taiwan: Foodie's Paradise. 5 Historic Henan. 5 Why Southeast Asia? . 6 The mutineers turning Bligh and his crew from the 'Bounty', 29th April 1789. The revolt came as a shock to Captain Bligh. Bligh and his followers were cast adrift without charts and with only meagre rations. They were given cutlasses but no guns. Yet Bligh and all but one of the men reached Timor safely on 14 June 1789. The journey took 47 days. Captain Bligh: History's Most Philippines. 6 Misunderstood Globetrotter? Australia on Sale. 7 by Christian Baines What transpired on the Bounty Captain’s Servant on the HMS contact with the Hawaiian Islands, Downunder Self Drive. 8 Those who owe everything they is just one chapter of Bligh’s story, Monmouth. The industrious where a dispute with the natives Spirit of Queensland. 9 know about Captain William Bligh one that for the most-part tells of young recruit served on several would end in the deaths of Cook Exploring Egypt. 9 to Hollywood could be forgiven for an illustrious naval career and of ships before catching the attention and four Marines. This tragedy Ecuador's Tren Crucero. 10 thinking the man was a sociopath. a leader noted for his fairness and of Captain James Cook, the first however, led to Bligh proving him- South America . 10 In many versions of the tale, the (for the era) clemency. Bligh’s tem- European to set foot on the east self one of the British Navy’s most man whose leadership drove the per however, frequently proved his coast of Australia. -

Becoming Art: Some Relationships Between Pacific Art and Western Culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1995 Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific art and Western culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Cochrane, Susan, Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific ra t and Western culture, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, , University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2088 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. BECOMING ART: SOME RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PACIFIC ART AND WESTERN CULTURE by Susan Cochrane, B.A. [Macquarie], M.A.(Hons.) [Wollongong] 203 CHAPTER 4: 'REGIMES OF VALUE'1 Bokken ngarribimbun dorlobbo: ngarrikarrme gunwok kunmurrngrayek ngadberre ngarribimbun dja mak kunwarrde kne ngarribimbun. (There are two reasons why we do our art: the first is to maintain our culture, the second is to earn money). Injalak Arts and Crafts Corporate Plan INTRODUCTION In the last chapter, the example of bark paintings was used to test Western categories for indigenous art. Reference was also made to Aboriginal systems of classification, in particular the ways Yolngu people classify painting, including bark painting. Morphy's concept, that Aboriginal art exists in two 'frames', was briefly introduced, and his view was cited that Yolngu artists increasingly operate within both 'frames', the Aboriginal frame and the European frame (Morphy 1991:26). This chapter develops the theme of how indigenous art objects are valued, both within the creator society and when they enter the Western art-culture system. When aesthetic objects move between cultures the values attached to them may change. -

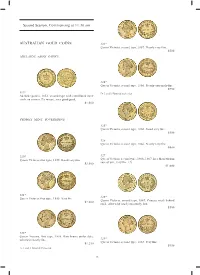

Second Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am AUSTRALIAN GOLD

Second Session, Commencing at 11.30 am AUSTRALIAN GOLD COINS 323* Queen Victoria, second type, 1857. Nearly very fi ne. $500 ADELAIDE ASSAY OFFICE 324* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Nearly extremely fi ne. $750 319* Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. Adelaide pound, 1852, second type with crenellated inner circle on reverse. Ex mount, very good/good. $1,000 SYDNEY MINT SOVEREIGNS 325* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Good very fi ne. $500 326 Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Nearly very fi ne. $400 320* 327 Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Good very fi ne. Queen Victoria, second type, 1866, 1867. In a Monetarium case of sale, very fi ne. (2) $3,000 $1,000 321* 328* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Very fi ne. Queen Victoria, second type, 1867. Contact mark behind $2,000 neck, otherwise nearly extremely fi ne. $500 322* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Rim bruise under date, otherwise nearly fi ne. 329* Queen Victoria, second type, 1867. Very fi ne. $1,250 $450 Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. 26 SYDNEY MINT HALF SOVEREIGNS 330* Queen Victoria, second type, 1868. Nearly extremely fi ne. $650 337* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1856. Nearly fi ne. $600 Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. 331* Queen Victoria, second type, 1870. Nearly uncirculated/ uncirculated. $600 338* Queen Victoria, second type, 1861. Good very fi ne. $700 339 332* Queen Victoria, second type, 1861. Very good. Queen Victoria, second type, 1870. Considerable mint $200 bloom, extremely fi ne. $800 340* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. -

Jane Awi Thesis (PDF 5MB)

“CREATING NEW FOLK OPERA FORMS OF APPLIED THEATRE FOR HIV AND AIDS EDUCATION IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA” [JANE PUMAI AWI] [DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY] Master of Arts (Humanities) Bachelor of Arts in Literature Diploma in Theatre Arts Supervisors Professor Brad Haseman Dr. Andrea Baldwin Dr. Greg Murphy Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Creative Industry Queensland University of Technology 2014 KEYWORDS Communication, awareness, HIV and AIDS, Voluntary, Testing and Counselling, folk opera, applied theatre, theatre for development, drama, script, performance, performativity, theatre, theatricality, intercultural theatre, intra-cultural, indigenous knowledge, cultural performances, metaphor, signs, symbols, Papua New Guinean worldview, Melanesian way, Papua New Guinea and Kumul. Table of Contents i Abstract This research investigated the potential of folk opera as a tool for HIV and AIDS education in Papua New Guinea. It began with an investigation on the indigenous performativities and theatricalities of Papua New Guineans, conducting an audit of eight selected performance traditions in Papua New Guinea. These traditions were analysed, and five cultural forms and twenty performance elements were drawn out for further exploration. These elements were fused and combined with theatre techniques from western theatre traditions, through a script development process involving Australians, Papua New Guineans and international collaborators. The resulting folk opera, entitled Kumul, demonstrates what Murphy (2010) has termed story force, picture force, and feeling force, in the service of a story designed to educate Papua New Guinean audiences about HIV and the need to adopt safer sexual practices. Kumul is the story of a young man faced with decisions on whether or not to engage in risky sexual behaviours. -

National Newsletter

National Newsletter Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material (Inc.) ISSN 1834-0598 No 124 March 2013 Contents 2 President’s Report 3 A new vision: redesigning the UC conservation course 5 University of Canberra update – a new laboratory 6 Marcelle Scott – an appreciation by two former students 6 Special Interest Group News 7 AICCM Bulletin Editor – Farewell to the old and welcome to the new 8 The ICOM-CC 17th Triennial Conference in Melbourne 2014 10 The Meaning of End of an era: Materials in Modern and Contemporary Art Marcelle Scott retires 13 Conference Report 14 Workshop Review from the CCMC 15 Course Review 16 The 2012 winners of the ADFAS/AICCM Marcelle Scott (CCMC) & Dr Ian MacLeod Prize for Conservation (WAM) at the Heritage Victoria Labs. Student of the Year Photo: Jane Walton student, CCMC 18 Christmas in the divisions Institutional News 20 NSW 24 ACT 24 SA 25 Vic 27 Trawling the Internet Photographic Conference, Objects SIG meets in Konservator Ken finds love Te Papa, Wellington Melbourne President’s Report President’s Report In early March, National Council met that Council can explore to further Other major events coming up soon are in Melbourne for our annual two day, the association. Creative Partnerships our National Conference – in Adelaide face-to-face meeting. We use these two Australia aims to be a ‘one-stop-shop’ in October this year. A very interesting days to develop a focus for the coming to promote, encourage and facilitate and challenging theme – Conservation year and to choose some projects that business, philanthropic and donor and Conservators in a Wider Context provide a balance – some that are support for the arts. -

Pacific Island History Poster Profiles

Pacific Island History Poster Profiles A Note for Teachers Acknowledgements Index of Profiles This Profiles are subject to copyright. Photocopying and general reproduction for teaching purposes is permitted. Reproduction of this material in part or whole for commercial purposes is forbidden unless written consent has been obtained from Queensland University of Technology. Requests can be made through the acknowldgements section of this pdf file. A Note for Teachers This series of National History Posters has been designed for individual and group Classroom use and Library display in secondary schools. The main aim is to promote in children an interest in their national history. By comparing their nation's history with what is presented on other Posters, students will appreciate the similarities and differences between their own history and that of their Pacific Island neighbours. The student activities are designed to stimulate comparison and further inquiry into aspects of their own and other's past. The National History Posters will serve a further purpose when used as a permanent display in a designated “History” classroom, public space or foyer in the school or for special Parent- Teacher nights, History Days and Education Days. The National History Posters do not offer a complete survey of each nation's history. They are only a profile. They are a short-cut to key people, key events and the broad sweep of history from original settlement to the present. There are many gaps. The posters therefore serve as a stimulus for students to add, delete, correct and argue about what should or should not be included in their Nation's History Profile. -

USP Workshop

USP workshop Thursday 25 August 2016 “Researchers need to be free, to be open to the immersive experience of exploratory research, receptive to the power of what you read, attentive to the voices you encounter, allow them to move you, change your minds and generate new understandings… archives are often the start of many histories yet to be written or imagined. These future possibilities are precious and exciting.” (Ballantyne, 2015) The aim of PMB Help with long-term preservation of the documentary heritage of the Pacific Islands and to make it accessible. What the PMB does • Arrange, lists and copies archives • Provide access • Provide support to researchers • Supports archives and libraries in the Pacific Islands Why? Archives are often in vulnerable conditions out in the islands —Cyclones, tsunamis —Mould, pests —Political instability —Few resources Scholars, students and Church of Melanesia archives in Santo, researchers of all kinds use Vanuatu, 2012 archives for their work Vulnerable documents The Bureau’s collection Over 4000 reels of microfilm Reels in PMB Ms. Series by Content Government Diaries Letters Church/ Whaling mission Types of documents Letters Diaries Photographs Novels, stories, music Dictionaries Church and mission records Company records Poster promoting maternal & child health in PNG, c.1956. (Jean Chambers collection, PMB 1255/1; PMB Photo9/01.) Types of documents Shipping registers Youth and womens’ group newsletters Newspapers Scientific papers Broadcast reports (ABC) Minutes and accounts Posters Poster advertising the Goroka show, 1968 (Norman Wilson papers, PMB 1246/42.) PMB Photograph Collection Over 80 photographic collections 1849- Solomon Islands PNG Cook Islands Vanuatu Samoa Niue PMB Photo 43. -

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Catalogue of South Seas

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Room 4201, Coombs Building College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia Telephone: (612) 6125 2521 Fax: (612) 6125 0198 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pambu Catalogue of South Seas Photograph Collections Chronologically arranged, including provenance (photographer or collector), title of record group, location of materials and sources of information. Amended 18, 30 June, 26 Jul 2006, 7 Aug 2007, 11 Mar, 21 Apr, 21 May, 8 Jul, 7, 12 Aug 2008, 8, 20 Jan 2009, 23 Feb 2009, 19 & 26 Mar 2009, 23 Sep 2009, 19 Oct, 26, 30 Nov, 7 Dec 2009, 26 May 2010, 7 Jul 2010; 30 Mar, 15 Apr, 3, 28 May, 2 & 14 Jun 2011, 17 Jan 2012. Date Provenance Region Record Group & Location &/or Source Range Description 1848 J. W. Newland Tahiti Daguerreotypes of natives in Location unknown. Possibly in South America and the South the Historic Photograph Sea Islands, including Queen Collection at the University of Pomare and her subjects. Ref Sydney. (Willis, 1988, p.33; SMH, 14 Mar.1848. and Davies & Stanbury, 1985, p.11). 1857- Matthew New Guinea; Macarthur family albums, Original albums in the 1866, Fortescue Vanuatu; collected by Sir William possession of Mr Macarthur- 1879 Moresby Solomon Macarthur. Stanham. Microfilm copies, Islands Mitchell Library, PXA4358-1. 1858- Paul Fonbonne Vanuatu; New 334 glass negatives and some Mitchell Library, Orig. Neg. Set 1933 Caledonia, prints. 33. Noumea, Isle of Pines c.1850s- Presbyterian Vanuatu Photograph albums - Mitchell Library, ML 1890s Church of missions. -

Harvesting Development

HARVESTING DEVELOPMENT The Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS) is funded by the govern- ments of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden via the Nordic Council of Ministers, and works to encourage and support Asian studies in the Nordic countries. In so doing, NIAS has been publishing books since 1969, with more than one hundred titles produced in the last decade. Nordic Council of Ministers HARVESTING DEVELOPMENT THE CONSTRUCTION OF FRESH FOOD MARKETS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA Karl Benediktsson Copyright © Karl Benediktsson 2002 All rights reserved. First Published in Denmark by Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (Simultaneously published in North America by The University of Michigan Press) Printed in Singapore No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Benediktsson, Karl Harvesting development : the construction of fresh food markets in Papua New Guinea 1.Food supply - Papua New Guinea 2.Farm produce - Papua New Guinea I.Title II.Nordic Institute of Asian Studies 381'.4'5'6413'009953 ISBN 87-87062-92-5 (cloth) ISBN 87-87062-91-7 (paper) Contents Illustrations … vi Tables … viii Vignettes … viii Acknowledgements … ix Abbreviations … xii 1Introduction … 1 2Markets, commoditization, and actors: spacious concepts … 22 3Faces in the crowd: Lives and networks of selected actors … 54 4Fresh food movements in a fragmented national -

September Una Voce JOURNAL of the PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION of AUSTRALIA INC (Formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc)

ISSN 1442-6161, PPA 224987/00025 2006, No 3 - September Una Voce JOURNAL OF THE PAPUA NEW GUINEA ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA INC (formerly the Retired Officers Association of Papua New Guinea Inc) Patrons: His Excellency Major General Michael Jeffery AC CVO MC (Retd) Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Mrs Roma Bates; Mr Fred Kaad OBE The Christmas Luncheon In This Issue will be held on IN 100 WORDS OR LESS 3 Sunday 3 December 2006 NOTES FROM THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 6 Mandarin Club Sydney NEWS FROM SOUTH AUSTRALIA 7 FAREWELL FROM THE AIVOS APTS 8 Full details in next issue PNG….IN THE NEWS 8 Please get your replies in quickly. LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 10 Invite or meet up with old friends from SUPERANNUATION 11 your past and reminisce about days gone PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU UPDATE 12 by over a glass of wine and a Chinese BOMB DISPOSAL POTSDAM PLANTATION 14 banquet. Extended families, PROGRESS ON THE OLD friends, children and grandchildren of EUROPEAN/BADIHAGWA CEMETERY 15 members are most welcome and we can IAN ROWLES 16 organize tables to accommodate all ages THE LOOP 20 and interests. Jot the date in your FIRST EXPERIENCES WITH CREDIT CARD 21 diary now and start making those WHO'S EVER HEARD OF THE ‘PAPUA POLICE’?? phone calls! 22 This December’s luncheon will be the ANTON’S ESCAPADES II 25 last at the Mandarin Club in Sydney. The EARLY YEARS IN NEW GUINEA 26 club is to be re-developed. Your HELP WANTED 28 committee is looking for an alternative REUNIONS 30 venue which is central, close to transport BOOK NEWS AND REVIEWS 31 and parking and will provide a great A FRAMED NAMATJIRA PRINT GOES TO ERAVE atmosphere. -

Some Relationships Between Pacific Art and Western Culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1995 Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific art and Western culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Cochrane, Susan, Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific ra t and Western culture, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, , University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2088 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. BECOMING ART: SOME RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PACIFIC ART AND WESTERN CULTURE VOL II by Susan Cochrane, B.A. [Macquarie], M.A. (Hons.) [Wollongong] '•8KSSSK LIBRARY 409 CHAPTER 8: ART AND ABORIGINALITY1 Tyerabarrbowaryaou (I shall never become a white man) Pemulwuy2 The circumstances of urban3 Aboriginal artists and the nature of their art, discussed in this chapter, make some interesting contrasts with those of urban-based Papua New Guinea artists. But the chapter's main objective is to identify how individual artists, displaced from their cultural traditions, have undertaken the search for their own Aboriginal identity through art. 'Aboriginally' is explored in a number of ways. As well as identifying an individual's desire to unite with their Aboriginal background and culture, Aboriginality has also come to mean the power to influence others to recognise the effects 1 Sections of this chapter were published as 'Strong Ai Bilong Em' in Dark and Rose (eds) 1993. 2 Pemulwuy was a leader of the Eora people (Aboriginal tribe of the Port Jackson area) who led the resistance against the first colonisers in the 1770s-1780s (Willmot 1987).