SUSAN COCHRANE Art in the Contemporary Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMS112 1978-1979 Lowres Web

--~--------~--------------------------------------------~~~~----------~-------------- - ~------------------------------ COVER: Paul Webber, technical officer in the Herpetology department searchers for reptiles and amphibians on a field trip for the Colo River Survey. Photo: John Fields!The Australian Museum. REPORT of THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM TRUST for the YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE , 1979 ST GOVERNMENT PRINTER, NEW SOUTH WALES-1980 D. WE ' G 70708K-1 CONTENTS Page Page Acknowledgements 4 Department of Palaeontology 36 The Australian Museum Trust 5 Department of Terrestrial Invertebrate Ecology 38 Lizard Island Research Station 5 Department of Vertebrate Ecology 38 Research Associates 6 Camden Haven Wildlife Refuge Study 39 Associates 6 Functional Anatomy Unit.. 40 National Photographic Index of Australian Director's Research Laboratory 40 Wildlife . 7 Materials Conservation Section 41 The Australian Museum Society 7 Education Section .. 47 Letter to the Premier 9 Exhibitions Department 52 Library 54 SCIENTIFIC DEPARTMENTS Photographic and Visual Aid Section 54 Department of Anthropology 13 PublicityJ Pu bl ications 55 Department of Arachnology 18 National Photographic Index of Australian Colo River Survey .. 19 Wildlife . 57 Lizard Island Research Station 59 Department of Entomology 20 The Australian Museum Society 61 Department of Herpetology 23 Appendix 1- Staff .. 62 Department of Ichthyology 24 Appendix 2-Donations 65 Department of Malacology 25 Appendix 3-Acknowledgements of Co- Department of Mammalogy 27 operation. 67 Department of Marine -

Newsletter Principal Mr S V Gargiulo QSO, Bsc, Dip

Manurewa High School Newsletter Principal Mr S V Gargiulo QSO, BSc, Dip. Tchg February 2014 IMPORTANT DATES Dear Parents / Guardians Welcome to new families in our community. The school newsletter, published twice a term, acts as a Saturday 1 March means of connection with Manurewa High School and is one way of remaining informed of events Waka Ama Auckland Champs and student achievement. We are very proud of our achievements in and out of the classroom as you Monday 3 March will read in this newsletter. We do know that having families and community connected to the school Counties/Manukau Swimming is essential to these achievements. Another resource for accessing information is the school website, Champs www.manurewa.school.nz which includes a parent portal – further information on this overleaf. Wednesday 5 March It was great to see so many students make use of the opportunity to return to school early to confirm Mentor and Parents Catch Up, their courses. These students are giving themselves every chance to be able to take courses that will fit MHS Staffroom 6.30pm—8pm their career pathways. Thursday 6 March—Saturday 8 March Volleyball Auckland Champs Manurewa High School commences 2014 on a very positive note with outstanding 2013 NCEA results Saturday 8 March—Sunday 9 March as detailed in the graph below: Ohu and Ohana Yes Groups 2013—Pasifika Festival Auckland Monday 10 March Young Enterprise Eday Tuesday 11 March .Student ID Photos .Fie Fia Night (Tongan) Wednesday 12—Saturday 15 March Polyfest Thursday 13 March Fie Fia Night (Samoan) Friday 14 March STAFF ONLY DAY—Polyfest Friday Monday 17 March STAFF ONLY DAY Sunday 23—Saturday 29 March Summer Tournament Week Wednesday 26 March Production Camp, Willow Park Thursday 27 March While the NCEA results are very encouraging at all levels, I am especially pleased with the Experience Fonterra Day performance of the 2013 Year 11 students who made the most significant improvement and moved the school to above the national average. -

Captain Bligh

www.goglobetrotting.com THE MAGAZINE FOR WORLD TRAVELLERS - SPRING/SUMMER 2014 CANADIAN EDITION - No. 20 CONTENTS Iceland-Awesome Destination. 3 New Faces of Goway. 4 Taiwan: Foodie's Paradise. 5 Historic Henan. 5 Why Southeast Asia? . 6 The mutineers turning Bligh and his crew from the 'Bounty', 29th April 1789. The revolt came as a shock to Captain Bligh. Bligh and his followers were cast adrift without charts and with only meagre rations. They were given cutlasses but no guns. Yet Bligh and all but one of the men reached Timor safely on 14 June 1789. The journey took 47 days. Captain Bligh: History's Most Philippines. 6 Misunderstood Globetrotter? Australia on Sale. 7 by Christian Baines What transpired on the Bounty Captain’s Servant on the HMS contact with the Hawaiian Islands, Downunder Self Drive. 8 Those who owe everything they is just one chapter of Bligh’s story, Monmouth. The industrious where a dispute with the natives Spirit of Queensland. 9 know about Captain William Bligh one that for the most-part tells of young recruit served on several would end in the deaths of Cook Exploring Egypt. 9 to Hollywood could be forgiven for an illustrious naval career and of ships before catching the attention and four Marines. This tragedy Ecuador's Tren Crucero. 10 thinking the man was a sociopath. a leader noted for his fairness and of Captain James Cook, the first however, led to Bligh proving him- South America . 10 In many versions of the tale, the (for the era) clemency. Bligh’s tem- European to set foot on the east self one of the British Navy’s most man whose leadership drove the per however, frequently proved his coast of Australia. -

House Resolution

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES THIRTY-FIRST LEGISLATURE, 2021 STATE OF HAWAII HOUSE RESOLUTION REQUESTING THE HAWAII SISTER-STATE COMMITTEE TO EVALUATE AND DEVELOP RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE INITIATION OF A SISTER- STATE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE CITY OF AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND. 1 WHEREAS, due to its multicultural population since the days 2 of the Hawaiian Monarchy, Hawaii maintains a heritage of 3 international participation and cultural sensitivity that is 4 unparalleled in other states; and 5 6 WHEREAS, the State actively seeks to expand its 7 international ties and has an abiding interest in developing 8 goodwill, friendship, and economic relations between the people 9 of Hawaii and the people of many nations; and 10 11 WHEREAS, while Hawaii currently maintains eighteen sister- 12 state relationships, none are with any cities or provinces in 13 New Zealand; and 14 15 WHEREAS, Hawaii and New Zealand are part of the triangle of 16 Polynesia, and the indigenous people of Hawaii and New Zealand 17 share many cultural and language similarities; and 18 19 WHEREAS, collaboration with the many Maori and Polynesian 20 cultural institutes in New Zealand would be culturally 21 beneficial to Hawaii; and 22 23 WHEREAS, Hawaii has participated in the Pasifika Festival, 24 an annual Pacific Islands-themed festival typically held in 25 Western Springs, Auckland, New Zealand, since 2014; and 26 27 WHEREAS, New Zealand is consistently ranked as among the 28 top twenty countries for quality of education by the 29 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; and 30 31 WHEREAS, as an island nation in the middle of the Pacific 32 Ocean, New Zealand faces some of the same geographic challenges 2021—1961 HR HMSO ~ Page2 H.R. -

Tātou O Tagata Folau. Pacific Development Through Learning Traditional Voyaging on the Waka Hourua, Haunui

Tātou o tagata folau. Pacific development through learning traditional voyaging on the waka hourua, Haunui. Raewynne Nātia Tucker 2020 School of Social Sciences and Public Policy, Faculty of Culture and Society A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... i Abstract ........................................................................................................................ v List of Figures .............................................................................................................. vi List of Tables ............................................................................................................... vii List of Appendices ...................................................................................................... viii List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................... ix Glossary ....................................................................................................................... x Attestation of Authorship ............................................................................................. xiii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... xiv Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................ -

Becoming Art: Some Relationships Between Pacific Art and Western Culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1995 Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific art and Western culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Cochrane, Susan, Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific ra t and Western culture, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, , University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2088 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. BECOMING ART: SOME RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PACIFIC ART AND WESTERN CULTURE by Susan Cochrane, B.A. [Macquarie], M.A.(Hons.) [Wollongong] 203 CHAPTER 4: 'REGIMES OF VALUE'1 Bokken ngarribimbun dorlobbo: ngarrikarrme gunwok kunmurrngrayek ngadberre ngarribimbun dja mak kunwarrde kne ngarribimbun. (There are two reasons why we do our art: the first is to maintain our culture, the second is to earn money). Injalak Arts and Crafts Corporate Plan INTRODUCTION In the last chapter, the example of bark paintings was used to test Western categories for indigenous art. Reference was also made to Aboriginal systems of classification, in particular the ways Yolngu people classify painting, including bark painting. Morphy's concept, that Aboriginal art exists in two 'frames', was briefly introduced, and his view was cited that Yolngu artists increasingly operate within both 'frames', the Aboriginal frame and the European frame (Morphy 1991:26). This chapter develops the theme of how indigenous art objects are valued, both within the creator society and when they enter the Western art-culture system. When aesthetic objects move between cultures the values attached to them may change. -

Contemporary Pacific Status Report a Snapshot of Pacific Peoples in New Zealand

Contemporary Pacific Status Report A snapshot of Pacific peoples in New Zealand i Ministry for Pacific Peoples Contemporary Pacific Status Report A snapshot of Pacific peoples in New Zealand The Contemporary Pacific Status Report offers a present-day snapshot of the Pacific peoples population in New Zealand. Information from various data sources, including the 2013 Census, are brought together into one easily accessible document and highlights the current position of Pacific peoples in New Zealand. PaMiniscitry for fic Peoples Te Manatu mo Nga Iwi o Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa ISSN 2537-687X (Print) ISSN 2537-6888 (Online) ii Ministry for Pacific Peoples Contemporary Pacific Status Report iii Table of Contents Introduction 1–4 Pacific peoples in New Zealand 5–8 Where in New Zealand do Pacific peoples live? 9–11 Education 12–17 Labour market outcomes 18–32 Housing situation 33–38 Appendices 76 Households 39–42 Appendix 1: Background 77 information on data sources Health 43–48 Appendix 2: List of tables 79 and figures Wellbeing 49–55 Appendix 3: Classification of 81 Pacific peoples ethnicity at Population growth 56–59 Statistics New Zealand Appendix 4: Selected NZGSS 83 Crime and justice 60–64 measures by ethnicity – April 2014 – March 2015 Pacific languages spoken 65–69 Appendix 5: Terminations (abortion) 86 by ethnicity and age of women Religion 70–75 (Annual – December) 2014 Acknowledgements The Ministry for Pacific peoples would like to acknowledge the support of Statistics New Zealand in the collation and review of Census 2013 data and customised data, in particular Tom Lynskey and Teresa Evans. -

Waves of Exchange

Symposium Proceedings, 2020 Introduction: Waves of Exchange Brittany Myburgh, University of Toronto Their universe comprised not only land surfaces, but the surrounding ocean as far as they could traverse and exploit it... - Our Sea of Islands, Epeli Hau’ofa1 Oceania is connected by waves of movement, from ocean-faring migration to networks of information and exchange. Tongan scholar Epeli Hau’ofa has described Oceania as a “sea of islands,” or a sea of relationships and networks that challenges prescribed geographic boundaries and scales. Arguing for the theorization and use of the term ‘Oceania,’ to describe this zone, Hau’ofa seeks to subvert the ways in which European colonizers, from James Cook to Louis Antoine de Bougainville, conceptually and physically mapped the Pacific Ocean (Te Moana Nui) as islands scattered in a faraway sea.2 The Pacific has long held space in the Western imagination. Its presence, as Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues, is to be found in the West’s very “fibre and texture, in its sense of itself, in its language, in its silences and shadows, its margins and intersections.”3 The European activity of mapping the Pacific Ocean throughout the latter half of the eighteenth century was accompanied by the acquisition of material culture from within Oceania.4 The collection of 1 Epeli Hau'ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” The Contemporary Pacific , vol. 6, no. 1, (Spring 1994): 152. 2 Hau'ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” 151. 3 Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. (London: Zed Books, 1999): 14. 4 Attention is increasingly paid to provenance and biographies of objects in Oceanic collections to better assess the often fraught histories of encounter, trade, and appropriation or theft. -

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Māori Tourism Experiences

Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland Māori tourism experiences aucklandnz.com Tāmaki Makaurau A place desired by many Tāmaki Herenga Waka The place where many canoes gather These are the Māori names given to Auckland. They speak of our diverse landscapes, beautiful harbours and fertile soils. They speak of the coming together of different iwi (tribes) to meet and trade. Today, people from all over the world visit Tāmaki Makaurau for the same reasons – to experience our natural beauty and unique Māori culture. In the spirit of manaakitanga – hospitality, generosity and openness of spirit – we welcome our visitors as guests. Discover this spirit as you connect with the people, land Te Kotūiti Tuarua – Ngāti Paoa and stories that have shaped our region. Māori tourism experiences in the Auckland region Goat Island Matakana Great Barrier Island NORTH AUCKLAND HAURAKI GULF AND ISLANDS Tiritiri Matangi Island Whangaparaoa Rangitoto Island WEST AUCKLAND Waiheke Island Muriwai Beach AUCKLAND CENTRAL Piha Beach Hunua Ranges EAST Awhitu Peninsula AUCKLAND SOUTH AUCKLAND AUCKLAND HAURAKI GULF NORTH CENTRAL AND ISLANDS AUCKLAND Auckland Ghost Tours Hike Bike Ako Waiheke Island Pakiri Beach Horse Rides Kura Gallery Pōtiki Adventures Te Hana Te Ao Marama Okeanos Aotearoa Te Haerenga Guided Walks Tāmaki Hikoi Waiheke Horseworx Tāmaki Paenga Hira (Auckland War Memorial Museum) The Poi Room TIME Unlimited Tours Toru Tours Waka Quest Whanau Marama Māori Experiences Auckland Hike Bike Ako Ghost Tours Waiheke Island A lantern lit walking tour in Hike Bike Ako Waiheke Island – Walk Auckland CBD and Symonds and E-Cycle with Māori. We offer Street Cemetery visiting the most fully guided walking and electric historical streets with beguiling bicycle tours on Waiheke Island. -

Du Cericentre De Recherches

les études du Ceri Centre de Recherches Internationales One Among Many: Changing Geostrategic Interests and Challenges for France in the South Pacific Denise Fisher One Among Many: Changing Geostrategic Interests and Challenges for France in the South Pacific Abstract France, which is both an external and resident South Pacific power by virtue of its possessions there, pursues, or simply inherits, multiple strategic benefits. But the strategic context has changed in recent years. China's increased presence; consequent changes in the engagement of the US, Japan and Taiwan; and the involvement of other players in the global search for resources, means that France is one of many more with influence and interests in a region considered by some as a backwater. These shifts in a way heighten the value of France's strategic returns, while impacting on France's capacity to exert influence and pursue its own objectives in the region. At the same time, France is dealing with demands for greater autonomy and even independence from its two most valuable overseas possessions on which its influence is based, New Caledonia and French Polynesia. How it responds to these demands will directly shape the nature of its future regional presence, which is a strategic asset. Une puissance parmi d'autres : évolution des enjeux et défis géostratégiques de la France en Océanie Résumé Compte tenu des territoires qu’elle y possède encore, la France est en Océanie une puissance à la fois locale et extérieure. A ce titre, et quand elle ne se contente pas de bénéficier d’avantages hérités, elle poursuit des objectifs stratégiques multiples. -

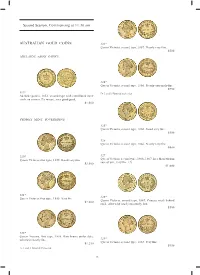

Second Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am AUSTRALIAN GOLD

Second Session, Commencing at 11.30 am AUSTRALIAN GOLD COINS 323* Queen Victoria, second type, 1857. Nearly very fi ne. $500 ADELAIDE ASSAY OFFICE 324* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Nearly extremely fi ne. $750 319* Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. Adelaide pound, 1852, second type with crenellated inner circle on reverse. Ex mount, very good/good. $1,000 SYDNEY MINT SOVEREIGNS 325* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Good very fi ne. $500 326 Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. Nearly very fi ne. $400 320* 327 Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Good very fi ne. Queen Victoria, second type, 1866, 1867. In a Monetarium case of sale, very fi ne. (2) $3,000 $1,000 321* 328* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Very fi ne. Queen Victoria, second type, 1867. Contact mark behind $2,000 neck, otherwise nearly extremely fi ne. $500 322* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1855. Rim bruise under date, otherwise nearly fi ne. 329* Queen Victoria, second type, 1867. Very fi ne. $1,250 $450 Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. 26 SYDNEY MINT HALF SOVEREIGNS 330* Queen Victoria, second type, 1868. Nearly extremely fi ne. $650 337* Queen Victoria, fi rst type, 1856. Nearly fi ne. $600 Ex J. and J. Edwards Collection. 331* Queen Victoria, second type, 1870. Nearly uncirculated/ uncirculated. $600 338* Queen Victoria, second type, 1861. Good very fi ne. $700 339 332* Queen Victoria, second type, 1861. Very good. Queen Victoria, second type, 1870. Considerable mint $200 bloom, extremely fi ne. $800 340* Queen Victoria, second type, 1866. -

Download/File/Dossier-7.Pdf World Meteorological Organization

Bibliography ABC News. (2013). ‘Kiribati fishermen rescued after four weeks lost at sea.’ 8 May 2013, http://www. abc.net.au/news/2013-05-08/an-fishermen-rescued-after-four-weeks-lost-at-sea/4676278. Abu-Lughod, L., & Lutz, C. A. (1990). ‘Introduction: Emotion, discourse, and the politics of everyday life.’ In C.A. Lutz & L. Abu-Lughod, (Eds.), Language and the politics of emotion (pp. 1–23). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Adger, W. N., Brown, K., Nelson, D. R., Berkes, F., Eakin, H., Folke, C., et al. (2011). ‘Resilience implications of policy responses to climate change.’ Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 2(5), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.133 Agence France Presse (2012). ‘Health fears as flood-ravaged Fiji begins clean-up.’ 3 April 2012. Akerblom, K. (1968). Astronomy and navigation in Polynesia and Micronesia. Stockholm: Ethnografiska Museet. Alkire, W. (1978). Coral islanders. Arlington Heights: AHM Press. Allen, A. (1993). ‘Architecture as social expression in Western Samoa: Axioms and models.’ Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, 5(1), 33–45. Anon. (2000). ‘1000 flee as sea begins to swallow up Pacific islands.’ The Independent. 29 November 2000. Anon. (2008). ‘Climate change and biodiversity in Melanesia.’ Ka ‘Elele: The Journal of Bishop Museum, Winter, 6–8. Aperau, A.M. (2005). ‘Focus. Home gardening after the cyclones. Cook Islands Ministry of Agriculture.’ Cook Islands News, 23 February 2005. Aron, R. (1957). The opium of the intellectuals (T. Kilmartin, Trans.). New York: Doubleday & Co. Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). (2011). ‘Climate change in the Pacific: Scientific assessment and new research.