D4.3 Report on Appraisal of Vaccine Benefit-Risk Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Statistics (Part 2): Interpreting Study Results

Statistical Notes II Descriptive statistics (Part 2): Interpreting study results A Cook and A Sheikh he previous paper in this series looked at ‘baseline’. Investigations of treatment effects can be descriptive statistics, showing how to use and made in similar fashion by comparisons of disease T interpret fundamental measures such as the probability in treated and untreated patients. mean and standard deviation. Here we continue with descriptive statistics, looking at measures more The relative risk (RR), also sometimes known as specific to medical research. We start by defining the risk ratio, compares the risk of exposed and risk and odds, the two basic measures of disease unexposed subjects, while the odds ratio (OR) probability. Then we show how the effect of a disease compares odds. A relative risk or odds ratio greater risk factor, or a treatment, can be measured using the than one indicates an exposure to be harmful, while relative risk or the odds ratio. Finally we discuss the a value less than one indicates a protective effect. ‘number needed to treat’, a measure derived from the RR = 1.2 means exposed people are 20% more likely relative risk, which has gained popularity because of to be diseased, RR = 1.4 means 40% more likely. its clinical usefulness. Examples from the literature OR = 1.2 means that the odds of disease is 20% higher are used to illustrate important concepts. in exposed people. RISK AND ODDS Among workers at factory two (‘exposed’ workers) The probability of an individual becoming diseased the risk is 13 / 116 = 0.11, compared to an ‘unexposed’ is the risk. -

EBM Notebook Numbers Needed to Treat Derived from Meta-Analysis: a Word of Caution

Evid Based Med: first published as 10.1136/ebm.8.2.36 on 1 March 2003. Downloaded from EBM notebook Numbers needed to treat derived from meta-analysis: a word of caution In clinical trials, treatment effects from binary outcomes, such the NNT will be applied, and information on the time horizon as “alive” or “dead”, can be presented in various ways (eg, rela- of the study (eg, the median follow up time). tive risk reduction [RRR] and absolute risk reduction We illustrate these points using the meta-analysis of [ARR]).1–2 (See glossary for definitions and calculations). Alter- randomised controlled trials investigating the effect of n-3 poly- natively, the number needed to treat (NNT) is an expression of the unsaturated fatty acids on clinical endpoints in patients with number of patients who need to be treated to prevent one coronary heart disease as an example.11–12 The meta-analysis additional adverse event.2–4 Mathematically, the NNT equals the found a 19% (CI 10% to 27%) RRR of overall mortality favour- reciprocal of the ARR. Many journals now report results from ing the use of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. In the clinical trials using the NNT, along with 95% confidence inter- Evidence-Based Medicine structured summary of this meta- vals (CIs).5 analysis, the NNT derived from a pooled risk difference, and 11 Since its introduction,3 a debate has ensued whether based on an average baseline risk of 9.5%, is 73 (CI 49 to 147). reporting NNTs from meta-analyses is misleading.467 ACP However, this estimate does not reflect the high variability of Journal Club and Evidence-Based Medicine have devoted attention baseline risk of the included trials. -

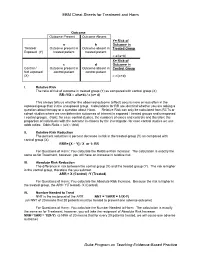

EBM Cheat Sheets for Treatment and Harm Duke Program on Teaching

EBM Cheat Sheets for Treatment and Harm Outcome Outcome Present Outcome Absent Y= Risk of a b Outcome in Treated/ Outcome present in Outcome absent in Treated Group Exposed (Y) treated patient treated patient = a/(a+b) X= Risk of c d Outcome in Control / Outcome present in Outcome absent in Control Group Not exposed control patient control patient (X) = c/(c+d) I. Relative Risk The ratio of risk of outcome in treated group (Y) as compared with control group (X) RR=Y/X = a/(a+b) / c (c+ d) This always tells us whether the observed outcome (effect) occurs more or less often in the exposed group than in the unexposed group. Calculations for RR are identical whether you are asking a question about therapy or a question about Harm. Relative Risk can only be calculated from RCTs or cohort studies where we can determine outcomes of interest in exposed / treated groups and unexposed / control groups. (Note: for case control studies, the numbers of cases and controls and therefore the proportion of individuals with the outcome is chosen by the investigator- for case control studies we use odds ratios: Odds Ratio = (a/c) / (b/d) II. Relative Risk Reduction The percent reduction is percent decrease in risk in the treated group (Y) as compared with control group (X) RRR= [X – Y] / X or 1- RR For Questions of Harm: You calculate the Relative Risk Increase: The calculation is exactly the same as for Treatment, however, you will have an increase in relative risk. III. Absolute Risk Reduction The difference in risk between the control group (X) and the treated group (Y). -

NUMBER NEEDED to TREAT (CONTINUATION) Confidence

Number Needed to treat Confidence Interval for NNT • As with other estimates, it is important that the uncertainty in the estimated number needed to treat is accompanied by a confidence interval. • A common method is that proposed by Cook and Sacket (1995) and based on calculating first the confidence interval NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT for the difference between the two proportions. • The result of this calculation is 'inverted' (ie: 1/CI) to give a (CONTINUATION) confidence interval for the NNT. Hamisu Salihu, MD, PhD Confidence Interval for NNT Confidence Interval for NNT • This computation assumes that ARR estimates from a sample of similar trials are normally distributed, so we can use the 95th percentile point from the standard normal distribution, z0.95 = 1.96, to identify the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% CI. Solution Class Exercise • In a parallel clinical trial to test the benefit of additional anti‐ hyperlipidemic agent to standard protocol, patients with acute Myocardial Infarction (MI) were randomly assigned to the standard therapy or the new treatment that contains standard therapy and simvastatin (an HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor). At the end of the study, of the 2223 patients in the control group 622 died as compared to 431 of 2221 patients in the Simvastatin group. – Calculate the NNT and the 95% CI for Simvastatin – Is Simvastatin beneficial as additional therapy in acute cases of MI? 1 Confidence Interval Number Needed to for NNT Treat • The NNT to prevent one additional death is 12 (95% • A negative NNT indicates that the treatment has a CI, 9‐16). -

A Number-Needed-To-Treat Analysis of the EMAX Trial

Efficacy of Umeclidinium/Vilanterol Versus Umeclidinium or Salmeterol: A Number-Needed-to-Treat Analysis of the EMAX Trial Poster No. 1091 (A3326) 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 Respiratory Medicine and Allergology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden; Centre de Pneumologie, Institut Universitaire de Cardiologie et de Pneumologie de Québec, Université Laval, QC, Canada; Department of Medicine, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University Medical Center Giessen and Marburg, Bjermer L , Maltais F , Vogelmeier CF , Naya I , Jones PW , 4 5 6 6 5 5 7 8 9 Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany, Member of the German Center for Lung Research (DZL); Global Specialty & Primary Care, GSK, Brentford, Middlesex, UK (at the time of the study) and RAMAX Ltd., Bramhall, Cheshire, UK; GSK, Brentford, Middlesex, UK; Precise Approach Ltd, contingent worker on assignment at Tombs L , Boucot I , Compton C , Lipson DA , Keeley T , Kerwin E GSK, Stockley Park West, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UK; 7Respiratory Clinical Sciences, GSK, Collegeville, PA, USA and Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 8GSK, Stockley Park West, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UK; 9Clinical Research Institute of Southern Oregon, Medford, OR, USA Background Results ● The relative treatment benefits with long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting Patients β -agonist (LAMA/LABA) combination therapy versus LAMA or LABA monotherapy have not been Table 1. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics Figure 2. Hazard ratio for a first moderate/severe exacerbation or CID at Week 24 2 ● Demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. demonstrated in symptomatic, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-free patients with COPD who have a low UMEC/VI vs UMEC UMEC/VI vs SAL UMEC/VI UMEC SAL risk of exacerbations. -

Routine Circumcision of Newborn Infants Re

A Trade-off Analysis of Routine Newborn Circumcision Dimitri A. Christakis, MD, MPH*‡; Eric Harvey, PharmD, MBA‡; Danielle M. Zerr, MD, MPH*; Chris Feudtner, MD, PhD*§; Jeffrey A. Wright, MD*; and Frederick A. Connell, MD, MPH‡i Abstract. Background. The risks associated with outine circumcision of newborn infants re- newborn circumcision have not been as extensively mains controversial.1–3 Although a recent evaluated as the benefits. Rpolicy statement by the American Academy Objectives. The goals of this study were threefold: 1) of Pediatrics recommended that parents be given to derive a population-based complication rate for new- accurate and unbiased information regarding the born circumcision; 2) to calculate the number needed to risks and benefits of the procedure,3 accomplishing harm for newborn circumcision based on this rate; and this task of well informed consent is hindered both 3) to establish trade-offs based on our complication rates and published estimates of the benefits of circumcision by the lack of precise information about potential including the prevention of urinary tract infections and harm and by the lack of clear ways to present this penile cancer. information. Methods. Using the Comprehensive Hospital Ab- The benefits of circumcision have been described stract Reporting System for Washington State, we retro- in numerous previous studies using a variety of spectively examined routine newborn circumcisions methodologies.4–8 Reported benefits include reduc- performed over 9 years (1987–1996). We used Interna- tion in the risk of penile cancer,9 urinary tract in- tional Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes fections (UTIs),4,5 and sexually transmitted diseas- to identify both circumcisions and complications and es.10,11 Although the extent to which circumcision limited our analyses to children without other surgical decreases the risk of each of these outcomes has procedures performed during their initial birth hospi- been debated,6,12–15 a consensus appears to be talization. -

Rex-Outterson

Clinical trial designs for non-traditional antibiotics John H. Rex, MD Kevin Outterson, JD Chief Medical Officer, F2G Ltd; Executive Director, CARB-X Expert-in-Residence, Wellcome Trust Professor of Law, Boston University Operating Partner, Advent Life Sciences Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Newsletter: http://amr.solutions Note: We are going to cover a LOT of material fairly quickly and taking notes will be hard. These slides will be available shortly via a newsletter and blog post on John’s website (see above). 2018-06-14 - Rex-Outterson - Duke-Margolis - Non-traditional antibiotic intro 1 Agenda • Defining scope: • The core problem • Language to guide conversation • Discussion of non-traditional products that… • Seek to treat infections • Seek to prevent infections • Why this matters to CARB-X: Summary & next steps • Supplemental slides • Useful literature, both general and from Animal Health 2018-06-14 - Rex-Outterson - Duke-Margolis - Non-traditional antibiotic intro 2 The core problem • All products must showcase their distinctive value • This is not a regulatory issue per se. Rather, this is what we naturally ask of anything • Prove to me that it works! • How is it better / useful? • In what settings can that advantage be seen? • For antibiotics, limits on the routinely possible studies (next slides) create a substantial hurdle • Superiority is (usually) out of reach • Non-inferiority studies are relatively unsatisfying • Beg for the bad news*: If you’re not clear on this, you are heading into a world of hurt *Swanson’s Rule #27 from Swanson's2018 Unwritten-06-14 - Rex Rules-Outterson of Management - Duke-Margolis. -

1. Relative Risk Reduction, Absolute Risk Reduction and Number Needed to Treat

Review Synthèse Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 1. Relative risk reduction, absolute risk reduction and number needed to treat Alexandra Barratt, Peter C. Wyer, Rose Hatala, Thomas McGinn, Antonio L. Dans, Sheri Keitz, Virginia Moyer, Gordon Guyatt, for the Evidence-Based Medicine Teaching Tips Working Group ß See related article page 347 hysicians, patients and policy-makers are influenced event without treatment. not only by the results of studies but also by how au- • Learn how to use absolute risk reductions to assess P thors present the results.1–4 Depending on which whether the benefits of therapy outweigh its harms. measures of effect authors choose, the impact of an inter- vention may appear very large or quite small, even though Calculating and using number needed to treat the underlying data are the same. In this article we present 3 measures of effect — relative risk reduction, absolute risk • Develop an understanding of the concept of number reduction and number needed to treat — in a fashion de- needed to treat (NNT) and how it is calculated. signed to help clinicians understand and use them. We • Learn how to interpret the NNT and develop an un- have organized the article as a series of “tips” or exercises. derstanding of how the “threshold NNT” varies de- This means that you, the reader, will have to do some work pending on the patient’s values and preferences, the in the course of reading this article (we are assuming that severity of possible outcomes and the adverse effects most readers are practitioners, as opposed to researchers (harms) of therapy. -

What Risk Factors Contribute to C Difficile Diarrhea?

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network Julia Fashner, MD; Marin Garcia, MD What risk factors contribute St. Joseph’s Family Medicine Residency Program, to C difficilediarrhea? South Bend, Ind Lisa Ribble, PharmD, BCPS St. Joseph’s Pharmacy EvidEncE-basEd answEr Residency Program, Mishawaka, Ind certain antibiotics and using length of stay (SOR: B, several good-quality Karen Crowell, MLIS A 3 or more antibiotics at one cohort studies). University of North time are associated with Clostridium Patient risk factors include advanced Carolina, Chapel Hill difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) age and comorbid conditions (SOR: B, sev- AssistAnt EDItOR (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, eral good-quality cohort studies). Richard Guthmann, 1 heterogeneous systematic review and Acid suppression medication is also a MD, MPH several good-quality cohort studies). risk factor for CDAD (SOR: B, 1 heteroge- University of Illinois at Chicago, Illinois Masonic Hospital risk factors include proximity neous systematic review and 2 good-quality Family Practice Residency to other patients with C difficile and longer cohort studies). Program, Chicago Evidence summary found that an increased number of antibiotics One systematic review found increased risk was a risk factor for CDAD (OR=1.49; 95% CI, of CDAD in patients taking cephalosporins, 1.23-1.81; NNH=44).4 Another retrospective penicillin, or clindamycin (tABLE 1).1 A sub- cohort study of 1187 inpatients at a Montreal sequent retrospective cohort investigation hospital found -

Measurement: Key Points Variable Types Continuous

Evidence Based Medicine Module 2 - Measurement: Key points Variable types Continuous - May assume any value within a given range - Examples: age, weight, height Discrete (also known as categorical) Types - dichotomous aka binary (e.g. yes/no; good/bad); - ordinal (e.g., the MRC scale) - nominal (e.g., race) - May only assume one of a select number of discrete values Measures of Frequency Disease Yes No Yes a b Treated No c d The exposure variable (aka, independent, explanatory, predictor) is whether the patient was treated The outcome variable (ka, dependent) is whether the patient developed the disease In this example, the frequency of a good outcome within the population may be expressed: (a+c)/(a+b+c+d) Similarly, the frequency of the exposure within the population may be expressed: (a+b)/(a+b+c+d) Prevalence: the frequency (or amount) of disease (or exposure) in a population at a given point in time Incidence: the frequency with which NEW events occur Risk: the probability of some event (0-1). However, without an indication of the time period, the quantification of risk is meaningless. Risk can only be calculated when incident data is available – which is to say that it is necessary to follow people who are initially free of the outcome of interest and to identify those who developed the outcome during the period of follow-up Formally defined as follows: (number of subjects who develop disease within a given period of time) / (number of subjects followed over the same period of time) An important obstacle to estimating risk is the problem of a changing denominator (may change either due to competing risks (e.g. -

50 Years of Pharmacovigilance: Unfinished Job Joan-Ramon Laporte

50 years of pharmacovigilance: unfinished job Joan-Ramon Laporte The role of pharmacoepidemiology in medicines regulation 108 market withdrawals in F, D & UK, 1961-93 Fulminant hepatitis Liver toxicity 24 Agranulocytosis Blood dyscrasias 12 Aplastic anaemia Thrombocytopenia Neuropsychiatric 11 Guillain-Barré syndrome Cutaneous 9 Stevens-Johnson syndrome Toxic epidermal necrolysis First-generation pharmacovigilance Attention to «unexpected» ADRs, of low incidence. Series of cases. Spontaneous reporting. Series of cases at hospital emergency departments. Clinical perspective: latency, clinical manifestations, outcome. • It does not inform on incidence. • It does not inform on risk. 108 market withdrawals in F, D & UK, 1961-93 Incidence (n per 106 and year) Fulminant hepatitis 5-10 Liver toxicity 24 Agranulocytosis 3-5 Blood dyscrasias 12 Aplastic anaemia 2 Thrombocytopenia 15-20 Neuropsychiatric 11 Guillain-Barré syndrome 15-20 Cutaneous 9 Stevens-Johnson syndrome 1 Toxic epidermal necrolysis <1 Incidence (n per 106 and year) Breast cancer 300 Gastrointestinal haemorrhage 400 Death by MI 870 CVA 2,300 Hospital admission by IC 2,200 Fall and hip fracture 800-1,400 Death by cancer (all) 1,730 NSAIDs Antiplatelet drugs Anticoagulants NSAIDs Diuretics Statins ACEI, ARB Gastrointestinal haemorrhage Type 2 diabetes NSAIDs Hormonal contraceptives Acute renal failure Glitazones CV mortality and morbidity PPIs Fall and hip fracture Psychotropic drugs Dementia, Alzheimer disease Opiate analgesics Antihypertensive drugs Sudden death Hypnotics Anticholinergic drugs H1 antihistamines Antipsychotic drugs Number needed to treat, NNT 1 AR = RE – RĒ NNT = × 100 AR NNH: Number Needed to Harm The risk can be estimated. The relative risk gives a clinical and epidemiological perspective. The attributable risk depends on the incidence and the relative risk. -

Number Needed to Treat (NNT): Implication in Rheumatology Clinical Practice M Osiri, M E Suarez-Almazor, G a Wells, V Robinson, P Tugwell

316 EXTENDED REPORT Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.62.4.316 on 1 April 2003. Downloaded from Number needed to treat (NNT): implication in rheumatology clinical practice M Osiri, M E Suarez-Almazor, G A Wells, V Robinson, P Tugwell ............................................................................................................................. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:316–321 Objective: To calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH) from the data in rheumatology clinical trials and systematic reviews. Methods: The NNTs for the clinically important outcome measures in the rheumatology systematic reviews from the Cochrane Library, issue 2, 2000 and in the original randomised, double blind, con- trolled trials were calculated. The measure used for calculating the NNT in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) See end of article for interventions was the American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement or Paulus criteria; in authors’ affiliations osteoarthritis (OA) interventions, the improvement of pain; and in systemic sclerosis (SSc) interventions, ....................... the improvement of Raynaud’s phenomenon. The NNH was calculated from the rate of withdrawals Correspondence to: due to adverse events from the treatment. Dr P Tugwell, Center for Results: The data required for the calculation of the NNT were available in 15 systematic reviews and Global Health, University 11 original articles. For RA interventions, etanercept treatment for six months had the smallest NNT of Ottawa, Institute of (1.6; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4 to 2.0), whereas leflunomide had the largest NNH (9.6; 95% Population Health, 1 CI 6.8 to 16.7). For OA treatment options, only etodolac and tenoxicam produced significant pain Stewart Street, Room 312, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, relief compared with placebo (NNT=4.4; 95% CI 2.4 to 24.4 and 3.8; 95% CI 2.5 to 7.3, respec- K1N 6N5; tively).