1. Relative Risk Reduction, Absolute Risk Reduction and Number Needed to Treat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Statistics (Part 2): Interpreting Study Results

Statistical Notes II Descriptive statistics (Part 2): Interpreting study results A Cook and A Sheikh he previous paper in this series looked at ‘baseline’. Investigations of treatment effects can be descriptive statistics, showing how to use and made in similar fashion by comparisons of disease T interpret fundamental measures such as the probability in treated and untreated patients. mean and standard deviation. Here we continue with descriptive statistics, looking at measures more The relative risk (RR), also sometimes known as specific to medical research. We start by defining the risk ratio, compares the risk of exposed and risk and odds, the two basic measures of disease unexposed subjects, while the odds ratio (OR) probability. Then we show how the effect of a disease compares odds. A relative risk or odds ratio greater risk factor, or a treatment, can be measured using the than one indicates an exposure to be harmful, while relative risk or the odds ratio. Finally we discuss the a value less than one indicates a protective effect. ‘number needed to treat’, a measure derived from the RR = 1.2 means exposed people are 20% more likely relative risk, which has gained popularity because of to be diseased, RR = 1.4 means 40% more likely. its clinical usefulness. Examples from the literature OR = 1.2 means that the odds of disease is 20% higher are used to illustrate important concepts. in exposed people. RISK AND ODDS Among workers at factory two (‘exposed’ workers) The probability of an individual becoming diseased the risk is 13 / 116 = 0.11, compared to an ‘unexposed’ is the risk. -

Meta-Analysis of Proportions

NCSS Statistical Software NCSS.com Chapter 456 Meta-Analysis of Proportions Introduction This module performs a meta-analysis of a set of two-group, binary-event studies. These studies have a treatment group (arm) and a control group. The results of each study may be summarized as counts in a 2-by-2 table. The program provides a complete set of numeric reports and plots to allow the investigation and presentation of the studies. The plots include the forest plot, radial plot, and L’Abbe plot. Both fixed-, and random-, effects models are available for analysis. Meta-Analysis refers to methods for the systematic review of a set of individual studies with the aim to combine their results. Meta-analysis has become popular for a number of reasons: 1. The adoption of evidence-based medicine which requires that all reliable information is considered. 2. The desire to avoid narrative reviews which are often misleading. 3. The desire to interpret the large number of studies that may have been conducted about a specific treatment. 4. The desire to increase the statistical power of the results be combining many small-size studies. The goals of meta-analysis may be summarized as follows. A meta-analysis seeks to systematically review all pertinent evidence, provide quantitative summaries, integrate results across studies, and provide an overall interpretation of these studies. We have found many books and articles on meta-analysis. In this chapter, we briefly summarize the information in Sutton et al (2000) and Thompson (1998). Refer to those sources for more details about how to conduct a meta- analysis. -

FORMULAS from EPIDEMIOLOGY KEPT SIMPLE (3E) Chapter 3: Epidemiologic Measures

FORMULAS FROM EPIDEMIOLOGY KEPT SIMPLE (3e) Chapter 3: Epidemiologic Measures Basic epidemiologic measures used to quantify: • frequency of occurrence • the effect of an exposure • the potential impact of an intervention. Epidemiologic Measures Measures of disease Measures of Measures of potential frequency association impact (“Measures of Effect”) Incidence Prevalence Absolute measures of Relative measures of Attributable Fraction Attributable Fraction effect effect in exposed cases in the Population Incidence proportion Incidence rate Risk difference Risk Ratio (Cumulative (incidence density, (Incidence proportion (Incidence Incidence, Incidence hazard rate, person- difference) Proportion Ratio) Risk) time rate) Incidence odds Rate Difference Rate Ratio (Incidence density (Incidence density difference) ratio) Prevalence Odds Ratio Difference Macintosh HD:Users:buddygerstman:Dropbox:eks:formula_sheet.doc Page 1 of 7 3.1 Measures of Disease Frequency No. of onsets Incidence Proportion = No. at risk at beginning of follow-up • Also called risk, average risk, and cumulative incidence. • Can be measured in cohorts (closed populations) only. • Requires follow-up of individuals. No. of onsets Incidence Rate = ∑person-time • Also called incidence density and average hazard. • When disease is rare (incidence proportion < 5%), incidence rate ≈ incidence proportion. • In cohorts (closed populations), it is best to sum individual person-time longitudinally. It can also be estimated as Σperson-time ≈ (average population size) × (duration of follow-up). Actuarial adjustments may be needed when the disease outcome is not rare. • In an open populations, Σperson-time ≈ (average population size) × (duration of follow-up). Examples of incidence rates in open populations include: births Crude birth rate (per m) = × m mid-year population size deaths Crude mortality rate (per m) = × m mid-year population size deaths < 1 year of age Infant mortality rate (per m) = × m live births No. -

CHAPTER 3 Comparing Disease Frequencies

© Smartboy10/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images CHAPTER 3 Comparing Disease Frequencies LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end of this chapter the reader will be able to: ■ Organize disease frequency data into a two-by-two table. ■ Describe and calculate absolute and relative measures of comparison, including rate/risk difference, population rate/risk difference, attributable proportion among the exposed and the total population and rate/risk ratio. ■ Verbally interpret each absolute and relative measure of comparison. ■ Describe the purpose of standardization and calculate directly standardized rates. ▸ Introduction Measures of disease frequency are the building blocks epidemiologists use to assess the effects of a disease on a population. Comparing measures of disease frequency organizes these building blocks in a meaningful way that allows one to describe the relationship between a characteristic and a disease and to assess the public health effect of the exposure. Disease frequencies can be compared between different populations or between subgroups within a population. For example, one might be interested in comparing disease frequencies between residents of France and the United States or between subgroups within the U.S. population according to demographic characteristics, such as race, gender, or socio- economic status; personal habits, such as alcoholic beverage consump- tion or cigarette smoking; and environmental factors, such as the level of air pollution. For example, one might compare incidence rates of coronary heart disease between residents of France and those of the United States or 57 58 Chapter 3 Comparing Disease Frequencies among U.S. men and women, Blacks and Whites, alcohol drinkers and nondrinkers, and areas with high and low pollution levels. -

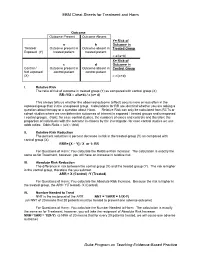

EBM Cheat Sheets for Treatment and Harm Duke Program on Teaching

EBM Cheat Sheets for Treatment and Harm Outcome Outcome Present Outcome Absent Y= Risk of a b Outcome in Treated/ Outcome present in Outcome absent in Treated Group Exposed (Y) treated patient treated patient = a/(a+b) X= Risk of c d Outcome in Control / Outcome present in Outcome absent in Control Group Not exposed control patient control patient (X) = c/(c+d) I. Relative Risk The ratio of risk of outcome in treated group (Y) as compared with control group (X) RR=Y/X = a/(a+b) / c (c+ d) This always tells us whether the observed outcome (effect) occurs more or less often in the exposed group than in the unexposed group. Calculations for RR are identical whether you are asking a question about therapy or a question about Harm. Relative Risk can only be calculated from RCTs or cohort studies where we can determine outcomes of interest in exposed / treated groups and unexposed / control groups. (Note: for case control studies, the numbers of cases and controls and therefore the proportion of individuals with the outcome is chosen by the investigator- for case control studies we use odds ratios: Odds Ratio = (a/c) / (b/d) II. Relative Risk Reduction The percent reduction is percent decrease in risk in the treated group (Y) as compared with control group (X) RRR= [X – Y] / X or 1- RR For Questions of Harm: You calculate the Relative Risk Increase: The calculation is exactly the same as for Treatment, however, you will have an increase in relative risk. III. Absolute Risk Reduction The difference in risk between the control group (X) and the treated group (Y). -

Understanding Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, and Related Terms: As Simple As It Can Get Chittaranjan Andrade, MD

Understanding Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, and Related Terms: As Simple as It Can Get Chittaranjan Andrade, MD Each month in his online Introduction column, Dr Andrade Many research papers present findings as odds ratios (ORs) and considers theoretical and relative risks (RRs) as measures of effect size for categorical outcomes. practical ideas in clinical Whereas these and related terms have been well explained in many psychopharmacology articles,1–5 this article presents a version, with examples, that is meant with a view to update the knowledge and skills to be both simple and practical. Readers may note that the explanations of medical practitioners and examples provided apply mostly to randomized controlled trials who treat patients with (RCTs), cohort studies, and case-control studies. Nevertheless, similar psychiatric conditions. principles operate when these concepts are applied in epidemiologic Department of Psychopharmacology, National Institute research. Whereas the terms may be applied slightly differently in of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India different explanatory texts, the general principles are the same. ([email protected]). ABSTRACT Clinical Situation Risk, and related measures of effect size (for Consider a hypothetical RCT in which 76 depressed patients were categorical outcomes) such as relative risks and randomly assigned to receive either venlafaxine (n = 40) or placebo odds ratios, are frequently presented in research (n = 36) for 8 weeks. During the trial, new-onset sexual dysfunction articles. Not all readers know how these statistics was identified in 8 patients treated with venlafaxine and in 3 patients are derived and interpreted, nor are all readers treated with placebo. These results are presented in Table 1. -

Outcome Reporting Bias in COVID-19 Mrna Vaccine Clinical Trials

medicina Perspective Outcome Reporting Bias in COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Clinical Trials Ronald B. Brown School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L3G1, Canada; [email protected] Abstract: Relative risk reduction and absolute risk reduction measures in the evaluation of clinical trial data are poorly understood by health professionals and the public. The absence of reported absolute risk reduction in COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials can lead to outcome reporting bias that affects the interpretation of vaccine efficacy. The present article uses clinical epidemiologic tools to critically appraise reports of efficacy in Pfzier/BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine clinical trials. Based on data reported by the manufacturer for Pfzier/BioNTech vaccine BNT162b2, this critical appraisal shows: relative risk reduction, 95.1%; 95% CI, 90.0% to 97.6%; p = 0.016; absolute risk reduction, 0.7%; 95% CI, 0.59% to 0.83%; p < 0.000. For the Moderna vaccine mRNA-1273, the appraisal shows: relative risk reduction, 94.1%; 95% CI, 89.1% to 96.8%; p = 0.004; absolute risk reduction, 1.1%; 95% CI, 0.97% to 1.32%; p < 0.000. Unreported absolute risk reduction measures of 0.7% and 1.1% for the Pfzier/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, respectively, are very much lower than the reported relative risk reduction measures. Reporting absolute risk reduction measures is essential to prevent outcome reporting bias in evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy. Keywords: mRNA vaccine; COVID-19 vaccine; vaccine efficacy; relative risk reduction; absolute risk reduction; number needed to vaccinate; outcome reporting bias; clinical epidemiology; critical appraisal; evidence-based medicine Citation: Brown, R.B. -

Copyright 2009, the Johns Hopkins University and John Mcgready. All Rights Reserved

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License. Your use of this material constitutes acceptance of that license and the conditions of use of materials on this site. Copyright 2009, The Johns Hopkins University and John McGready. All rights reserved. Use of these materials permitted only in accordance with license rights granted. Materials provided “AS IS”; no representations or warranties provided. User assumes all responsibility for use, and all liability related thereto, and must independently review all materials for accuracy and efficacy. May contain materials owned by others. User is responsible for obtaining permissions for use from third parties as needed. Section F Measures of Association: Risk Difference, Relative Risk, and the Odds Ratio Risk Difference Risk difference (attributable risk)—difference in proportions - Sample (estimated) risk difference - Example: the difference in risk of HIV for children born to HIV+ mothers taking AZT relative to HIV+ mothers taking placebo 3 Risk Difference From csi command, with 95% CI 4 Risk Difference Interpretation, sample estimate - If AZT was given to 1,000 HIV infected pregnant women, this would reduce the number of HIV positive infants by 150 (relative to the number of HIV positive infants born to 1,000 women not treated with AZT) Interpretation 95% CI - Study results suggest that the reduction in HIV positive births from 1,000 HIV positive pregnant women treated with AZT could range from 75 to 220 fewer than the number occurring if the -

Clinical Epidemiologic Definations

CLINICAL EPIDEMIOLOGIC DEFINATIONS 1. STUDY DESIGN Case-series: Report of a number of cases of disease. Cross-sectional study: Study design, concurrently measure outcome (disease) and risk factor. Compare proportion of diseased group with risk factor, with proportion of non-diseased group with risk factor. Case-control study: Retrospective comparison of exposures of persons with disease (cases) with those of persons without the disease (controls) (see Retrospective study). Retrospective study: Study design in which cases where individuals who had an outcome event in question are collected and analyzed after the outcomes have occurred (see also Case-control study). Cohort study: Follow-up of exposed and non-exposed defined groups, with a comparison of disease rates during the time covered. Prospective study: Study design where one or more groups (cohorts) of individuals who have not yet had the outcome event in question are monitored for the number of such events, which occur over time. Randomized controlled trial: Study design where treatments, interventions, or enrollment into different study groups are assigned by random allocation rather than by conscious decisions of clinicians or patients. If the sample size is large enough, this study design avoids problems of bias and confounding variables by assuring that both known and unknown determinants of outcome are evenly distributed between treatment and control groups. Bias (Syn: systematic error): Deviation of results or inferences from the truth, or processes leading to such deviation. See also Referral Bias, Selection Bias. Recall bias: Systematic error due to the differences in accuracy or completeness of recall to memory of past events or experiences. -

Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Determination of Effectiveness of Human Drugs and Biological Products Guidance for Industry

Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Determination of Effectiveness of Human Drugs and Biological Products Guidance for Industry U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) March 2019 Clinical/Medical Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Determination of Effectiveness of Human Drugs and Biological Products Guidance for Industry Additional copies are available from: Office of Communications, Division of Drug Information Center for Drug Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration 10001 New Hampshire Ave., Hillandale Bldg., 4th Floor Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002 Phone: 855-543-3784 or 301-796-3400; Fax: 301-431-6353; Email: [email protected] https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm and/or Office of Communication, Outreach, and Development Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Ave., Bldg. 71, rm. 3128 Silver Spring, MD 20993-0002 Phone: 800-835-4709 or 240-402-8010; Email: [email protected] https://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) March 2019 Clinical/Medical TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................ -

NUMBER NEEDED to TREAT (CONTINUATION) Confidence

Number Needed to treat Confidence Interval for NNT • As with other estimates, it is important that the uncertainty in the estimated number needed to treat is accompanied by a confidence interval. • A common method is that proposed by Cook and Sacket (1995) and based on calculating first the confidence interval NUMBER NEEDED TO TREAT for the difference between the two proportions. • The result of this calculation is 'inverted' (ie: 1/CI) to give a (CONTINUATION) confidence interval for the NNT. Hamisu Salihu, MD, PhD Confidence Interval for NNT Confidence Interval for NNT • This computation assumes that ARR estimates from a sample of similar trials are normally distributed, so we can use the 95th percentile point from the standard normal distribution, z0.95 = 1.96, to identify the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% CI. Solution Class Exercise • In a parallel clinical trial to test the benefit of additional anti‐ hyperlipidemic agent to standard protocol, patients with acute Myocardial Infarction (MI) were randomly assigned to the standard therapy or the new treatment that contains standard therapy and simvastatin (an HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor). At the end of the study, of the 2223 patients in the control group 622 died as compared to 431 of 2221 patients in the Simvastatin group. – Calculate the NNT and the 95% CI for Simvastatin – Is Simvastatin beneficial as additional therapy in acute cases of MI? 1 Confidence Interval Number Needed to for NNT Treat • The NNT to prevent one additional death is 12 (95% • A negative NNT indicates that the treatment has a CI, 9‐16). -

Evidence-Based Clinical Question Does Dantrolene Sodium Prevent Recurrent Exertional Rhabdomyolysis in Horses? M

EQUINE VETERINARY EDUCATION / AE / March 2007 97 Evidence-based Clinical Question Does dantrolene sodium prevent recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis in horses? M. A. HOLMES University of Cambridge, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ES, UK. Three part question of any other clinical manifestation of disease. An arbitrary level of >900 iu/l was selected as a case definition to provide In Thoroughbred horses (population) does treatment with a means of counting the number of animals that might be dantrolene sodium (intervention) reduce the recurrence of described as constituting a case of exertional rhabdomyolysis exertional rhabdomyolysis (outcome)? (ER). Clinical cases of ER may exhibit considerably greater levels of CK and it should not be implied that lower CK levels Clinical scenario may not be associated with clinical signs of ER. The key results are presented as absolute risk reductions A client requests advice on the prevention of recurrent (ARR) and relative risk reductions (RRR). The ARR indicates the exertional rhabdomyloysis (RER) for a Thoroughbred horse proportion of all horses in the treatment group that have an with a history of this condition. The veterinarian is aware that improved clinical outcome as a result of the treatment (i.e. the dantrolene sodium has been suggested as a suitable proportion of horses that benefit from dantrolene treatment). preventive treatment. Both the trials described here are unusual in that a number of horses are being treated that might not be considered Search strategy appropriate candidates for prophylactic treatment. There were 74 horses in the Edwards trial and 3 horses in the McKenzie Pubmed/Medline (1966–Jan 2007) (http://pubmed.org/): trial that failed to develop high CK levels either with or dantrolene AND equine.