CMI REPORT Rural Poverty in Malanje, Angola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.3 Angola Road Network

2.3 Angola Road Network Distance Matrix Travel Time Matrix Road Security Weighbridges and Axle Load Limits For more information on government contact details, please see the following link: 4.1 Government Contact List. Page 1 Page 2 Distance Matrix Uige – River Nzadi bridge 18 m-long and 4 m-wide near the locality of Kitela, north of Songo municipality destroyed during civil war and currently under rehabilitation (news 7/10/2016). Road Details Luanda The Government/MPLA is committed to build 1,100 km of roads in addition to 2,834 km of roads built in 2016 and planned rehabilitation of 7,083 km of roads in addition to 10,219 km rehabilitated in 2016. The Government goals will have also the support from the credit line of the R. of China which will benefit inter-municipality links in Luanda, Uige, Malanje, Cuanza Norte, Cuanza Sul, Benguela, Huambo and Bié provinces. For more information please vitsit the Website of the Ministry of Construction. Zaire Luvo bridge reopened to trucks as of 15/11/2017, this bridge links the municipality of Mbanza Congo with RDC and was closed for 30 days after rehabilitation. Three of the 60 km between MCongo/Luvo require repairs as of 17/11/2017. For more information please visit the Website of Agencia Angola Press. Works of rehabilitation on the road nr, 120 between Mbanza Congo (province Zaire) and the locality of Lukunga (province of Uige) of a distance of 111 km are 60% completed as of 29/9/2017. For more information please visit the Website of Agencia Angola Press. -

Inventário Florestal Nacional, Guia De Campo Para Recolha De Dados

Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais de Angola Inventário Florestal Nacional Guia de campo para recolha de dados . NFMA Working Paper No 41/P– Rome, Luanda 2009 Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais As florestas são essenciais para o bem-estar da humanidade. Constitui as fundações para a vida sobre a terra através de funções ecológicas, a regulação do clima e recursos hídricos e servem como habitat para plantas e animais. As florestas também fornecem uma vasta gama de bens essenciais, tais como madeira, comida, forragem, medicamentos e também, oportunidades para lazer, renovação espiritual e outros serviços. Hoje em dia, as florestas sofrem pressões devido ao aumento de procura de produtos e serviços com base na terra, o que resulta frequentemente na degradação ou transformação da floresta em formas insustentáveis de utilização da terra. Quando as florestas são perdidas ou severamente degradadas. A sua capacidade de funcionar como reguladores do ambiente também se perde. O resultado é o aumento de perigo de inundações e erosão, a redução na fertilidade do solo e o desaparecimento de plantas e animais. Como resultado, o fornecimento sustentável de bens e serviços das florestas é posto em perigo. Como resposta do aumento de procura de informações fiáveis sobre os recursos de florestas e árvores tanto ao nível nacional como Internacional l, a FAO iniciou uma actividade para dar apoio à monitorização e avaliação de recursos florestais nationais (MANF). O apoio à MANF inclui uma abordagem harmonizada da MANF, a gestão de informação, sistemas de notificação de dados e o apoio à análise do impacto das políticas no processo nacional de tomada de decisão. -

The Botanical Exploration of Angola by Germans During the 19Th and 20Th Centuries, with Biographical Sketches and Notes on Collections and Herbaria

Blumea 65, 2020: 126–161 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2020.65.02.06 The botanical exploration of Angola by Germans during the 19th and 20th centuries, with biographical sketches and notes on collections and herbaria E. Figueiredo1, *, G.F. Smith1, S. Dressler 2 Key words Abstract A catalogue of 29 German individuals who were active in the botanical exploration of Angola during the 19th and 20th centuries is presented. One of these is likely of Swiss nationality but with significant links to German Angola settlers in Angola. The catalogue includes information on the places of collecting activity, dates on which locations botanical exploration were visited, the whereabouts of preserved exsiccata, maps with itineraries, and biographical information on the German explorers collectors. Initial botanical exploration in Angola by Germans was linked to efforts to establish and expand Germany’s plant collections colonies in Africa. Later exploration followed after some Germans had settled in the country. However, Angola was never under German control. The most intense period of German collecting activity in this south-tropical African country took place from the early-1870s to 1900. Twenty-four Germans collected plant specimens in Angola for deposition in herbaria in continental Europe, mostly in Germany. Five other naturalists or explorers were active in Angola but collections have not been located under their names or were made by someone else. A further three col- lectors, who are sometimes cited as having collected material in Angola but did not do so, are also briefly discussed. Citation: Figueiredo E, Smith GF, Dressler S. -

A Estruturação Do Poder Local Em Angola E a Contribuição Do

A estruturação do poder local em angola e a contribuição do processo do encontro das comunidades para o seu fortalecimento e democratização A estruturação do poder local em Angola e a contribuição do processo do encontro das comunidades para o seu fortalecimento e democratização1 Belarmino Jelemi* Resumo A estruturação e o fortalecimento do poder local constituem dos principais fundamentos para a efectivação do processo de governação democrática em Angola. O conhecimento da natureza, perfil, forças e fraquezas das principais instituições e actores sociais locais afigura-se essencial para a operacionalização dos preceitos da Constituição da República de 2010 que marcou um avanço importante, estabelecendo para o poder local três segmen- tos interligados, nomeadamente as autarquias locais, as autoridades tradicionais e outras formas de participação dos cidadãos. Mesmo que as autarquias sejam merecedoras de mais mediatização, os outros pilares são também importantes e as formas de participação dos cidadãos, discutidas no presente texto, são a garantia da geração de freios e con- trapesos. Portanto, a relevância das autarquias para os cidadãos, em Angola, está muito dependente, entre outros, do aprofundamento do exercício da cidadania e dos sistemas de controlo locais. Palavras-chave: Constituição. Cidadania. Poder Local. http://dx.doi.org/10.5335/rjd.v28i1.4837 1 Este artigo é proveniente da avaliação das disciplinas Governação Democrática e Autarquias Locais, mi- nistradas pelo professor Doutor Giovani da Silva Corralo, docente convidado dos Programas de Mestrado da Universidade Agostinho Neto - Angola. O artigo obteve a expressa autorização do seu autor para esta publicação. * Director Geral da ADRA, Organização Não Governamental Angolana, onde trabalha a 15 anos. -

NPA Backgrounder

Angola Angola is a country in south-central Africa bordered by Namibia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia. Area: 1.246.700 square kilometers. Population: 16,941, 000. Demographic: Ovimbundu 37%, Kimbundu 25%, Bakongo 13%, 2%, European 1%, and 22% other. State Party to the Mine Ban Treaty (MBT). Cause and scope of the landmine problem Angola has been plagued by civil war since independence from Portugal in 1975 until the peace accords between the government and UNITA were signed the 4th of April 2002. Mines as well as a whole other slew of traditional ammunitions, explosive remnants of war (ERW) were used by both sides during the conflict, making Angola one of the most mine infected countries in the world. Large portions of the country are still not accessible due to mines and ERW, and it is estimated that one fifth of the population has its day to day life affected by mines and ERW. NPA history in the country Upon request by the UN, NPA involved itself with mine clearance in Angola in 1994. Initially, the task was to map the coastal provinces and other areas pinpointed as camps for demobilized soldiers, as well as clearing the main highway between Luanda and Malanje. Due to the mine problem and the huge distances, three separate bases for clearance were established throughout the country. From 1995 to 2004 these bases were located in the cities of Malanje, Luena and Lubango. In 2003 NPA took part in the country wide survey of the mine problem, and became responsible for 5 provinces in the northwestern part of Angola (Malanje, Kwanza Sul, Kwanza Norte, Uige, Zaire).The result of said survey created the base for strategic plans for mine clearance in Angola by national authorities (2006-2013). -

Angola-Water-Sector-Institutional

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR00004814 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT (AO-45010, AO-49700) ON A LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 35 MILLION (US$ 57 MILLION EQUIVALENT) AND A LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 74.1 MILLION (US$ 120 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA FOR THE AO-WATER SECTOR INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT February 28, 2020 Water Global Practice Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective {June 30, 2019}) Currency Unit = Angolan Kwanza (AOA) 340.27 AOA = US$1 US$1.39= SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 Regional Vice President: Hafez M. H. Ghanem Country Director: Abdoulaye Seck Regional Director(s): Ede Jorge Ijjasz-Vasquez, Simeon Kacou Ehui Senior Global Practice Director: Jennifer J. Sara Practice Manager: Maria Angelica Sotomayor Araujo Task Team Leader(s): Camilo Lombana Cordoba ICR Main Contributor: Rebecca Jean Gilsdorf ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AF Additional Financing AfDB African Development Bank AMU Asset Management Unit AOA Angolan Kwanza BP Bank Policy CBA Cost Benefit Analysis CPS Country Partnership Strategy DHS Demographic and Health Surveys DNA National Water Directorate (Direcção Nacional de Àguas) EA Environmental Assessment ECP Strategy to Combat Poverty (Estratégia de Combate à Pobreza) ERR Economic Rate of Return ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FCMU Financial -

Creating Markets in Angola : Country Private Sector Diagnostic

CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA MARKETS IN CREATING COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC SECTOR PRIVATE COUNTRY COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA Opportunities for Development Through the Private Sector COUNTRY PRIVATE SECTOR DIAGNOSTIC CREATING MARKETS IN ANGOLA Opportunities for Development Through the Private Sector About IFC IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of the world. In fiscal year 2018, we delivered more than $23 billion in long-term financing for developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity. For more information, visit www.ifc.org © International Finance Corporation 2019. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The findings, interpretations, views, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Finance Corporation or of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (the World Bank) or the governments they represent. -

Water and Sanitation

Evaluation Report Evaluation of ECHO´s Gobal Plan 2000 - Angola Sector: Water and Sanitation Country: ANGOLA Period: January till December 2000 Programme: ECHO/AGO/210/2000/01000 Author: Anton Rijsdijk, Hydrogeologist GERMAX Gerli GmbH - Germany Project : Evaluation Global Plan 2000 - Angola GMX-PN: EC/ECHO-03/2000 Period: November 2000 – January 2001 Contract: ECHO/EVA-B7-210/2000/01009 in Cooperation with GERMAX . GERLI GmbH • Bismarckstrasse 2-8 • D-52066 Aachen • Germany Evaluation Global Plan 2000 - Angola Report - Water and Sanitation This report has been produced at the request of the European Commission. The opinions and comments contained in this report reflect the opinions of the consultants only and not necessarily those of the European Commission. 2 Evaluation Global Plan 2000 - Angola Report - Water and Sanitation Structured Executive Summary for Cross Evaluation Purposes Evaluation Subject: Global Plan 2000 (GP) for Angola. The GP 2000 defined the assistance framework for EC/ECHO funded humanitarian operations in Angola, covering the fields of Health & Nutrition, Water & Sanitation and the distribution of Non-Food Items to IDPs in the country. Sector: Water & Sanitation during the reference period January – December 2000 Report No.: EC/ECHO-03/2000 Date of Evaluation: 14 November till 11 December 2000 Consultant Name: Anton Rijsdijk, Hydrologist, Germax Gerli GmbH Purpose and Methodology The purpose of the evaluation was to (i) assess the suitability and effectiveness of the GP2000, (ii) quantify the impact in terms of output and analyse the link between emergency, rehabilitation and development. The evaluation focussed on all three sectors, Health and Nutrition (H&N), Water and Sanitation (Watsan) and Non-Food items (NFI). -

Conferência Sobre O Cooperativismo O Cooperativismo Como Modelo Empresarial Sustentável E Rentável E O Seu Impacto No Fortalecimento Da Economia Angolana

CONFERÊNCIA SOBRE O COOPERATIVISMO O COOPERATIVISMO COMO MODELO EMPRESARIAL SUSTENTÁVEL E RENTÁVEL E O SEU IMPACTO NO FORTALECIMENTO DA ECONOMIA ANGOLANA COOPERATIVISMO AGROPECUÁRIO E O DESENVOLVIMENTO ECONÓMICO – SOCIAL EM ANGOLA Belarmino Jelembi Director Geral da ADRA [email protected] Feira agropecuária de Cacusso Malanje Luanda, 06.05.2016 INDICE i. O COOPERATIVISMO VS A OPÇÃO DE DESENVOLVIMENTO AGRÍCOLA ii. EXPERIÊNCIAS DE PROMOÇÃO DO COOPERATIVISMO E DESENVOLVIMENTO LOCAL(CACULA E OUTROS) iii. NOTAS FINAIS i. O COOPERATIVISMO VS A OPÇÃO DE DESENVOLVIMENTO AGRÍCOLA O cooperativismo agropecuário não pode ser abordado sem clarificar a opção de desenvolvimento agrícola do país. 1. O modelo dos grandes projectos agroindustriais? 2. O modelo assente na agricultura familiar? Ou 3. Ambos? a) Modelos que, não sendo iguais, coexistem com complementaridades, conflitos e contradições Complementaridades: • Pequenos agricultores assalariados nas grandes fazendas; • Integração de agricultores nas cadeias agroindustriais (aves; suínos; leite; soja) Conflitos: terra; água; recursos públicos Contradições: modelos distintos de agricultura (alimentação); relação com biodiversidade b) Significados distintos: econômico, social, cultural e ambiental c) Modernização com especialização produtiva vs. unidades diversificadas, reprodução familiar e desenvolvimento territorial (papel da produção auto-consumo) d) Cadeias integradas e especialização produtiva vs. agregação de valor e construção de mercados (mercado institucional, compras públicas) -

Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola

Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola By Aaron Laurence deGrassi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Professor Gillian P. Hart Professor Peter B. Evans Abstract Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola by Aaron Laurence deGrassi Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Fueled by a massive offshore deep-water oil boom, Angola has since the end of war in 2002 undertaken a huge, complex, and contradictory national reconstruction program whose character and dynamics have yet to be carefully studied and analyzed. What explains the patterns of such projects, who is benefitting from them, and how? The dissertation is grounded in the specific dynamics of cassava production, processing and marketing in two villages in Western Malanje Province in north central Angola. The ways in which Western Malanje’s cassava farmers’ livelihoods are shaped by transport, marketing, and an overall agrarian configuration illustrate how contemporary reconstruction – in the context of an offshore oil boom – has occurred through the specific conjunctures of multiple geo-historical processes associated with settler colonialism, protracted war, and leveraged liberalization. Such an explanation contrasts with previous more narrow emphases on elite enrichment and domination through control of external trade. Infrastructure projects are occurring as part of an agrarian configuration in which patterns of land, roads, and markets have emerged through recursive relations, and which is characterized by concentration, hierarchy and fragmentation. -

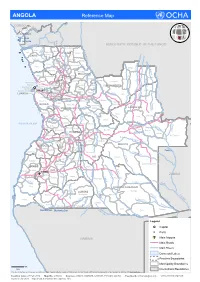

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO -

ANGOLA and DRC (KASAI) SITUATION 31 July 2017 CONGO Kinshasa

UNICEF ANGOLA AND DRC (KASAI) SITUATION 31 July 2017 CONGO Kinshasa Internally Cabinda displaced M* DEMOCRATIC people 1.4 Cabinda REPUBLIC OF Matadi CONGO Kananga 1,400,000 Mbuji-Mayi Mbanza-Congo DRC Kasai refugees 33,132* Zaire Area Mwene-Ditu in Angola Uíge Dundo Uige Kaniama Returnees Lucapa 271,687* Caxito Lunda Luanda Cuanza Norte Norte Malanje Refugee reception Luanda Ndalatando Malanje centres Saurimo Bengo Lunda Cholera Sul Kolwezi outbreak Cuanza ANGOLA Sumbe Sul Drought affected provinces Luena Solwezi Kuito Benguela Armyworm Huambo Bié infestation Huambo Benguela Moxico UNICEF DRC Refugees Needs ZAMBIA Menongue Lubango Huíla 33,132 people in need Namibe Mongu Cuando Namibe Cubango 26,500 children in need Cunene Ondjiva 50,000 people in need NAMIBIA of safe water Livingstone *Inter Agency operational update, 8 Aug 2017 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. UNICEF ANGOLA AND DRC (KASAI) RESPONSE 31 July 2017 Internally 1 DRC refugees 1 1 displaced Returnees in Angola people 1.4 M 33,132 271,687 *Inter Agency Operational update, 8 Aug 2017 UNICEF Refugees, Angola Needs UNICEF Angola Needs children under-five 33,132 26,500 50,000 people in 1.13 million 605,982 children 44,511 people in need children in need need of safe water people affected by affected by drought with SAM in the 3 most drought drought affected provinces UNICEF Refugees, Angola Response UNICEF Angola Response Results Gap Achieved Results Gap Achieved # of children