To Download the PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmitting Nation “Bordering” and the Architecture of the CBC in the 1930S1

e ssaY | essai TransmiTTing naTion “Bordering” and the architecture of the CBC in the 1930s1 Mi ChAeL WiNdOVer holds a doctorate in art > MiChael Windover history from the University of British Columbia. his dissertation was awarded the Phyllis-Lambert Prize and a revised version is forthcoming in a series on urban heritage with the Presses de l’Université du Québec as Art deco: A Mode of ational boundaries are as much con- Mobility. Windover is currently in the School of Nceptual as they are material. They Architecture at McGill University working on his delineate a space of belonging and mark a liminal region of identity production, Social Sciences and humanities research Council and yet are premised on a real, physical of Canada postdoctoral project: “Architectures of location with economic and social impli- radio: Sound design in Canada, 1925-1952.” cations. With this in mind, I introduce This article represents initial output from this the idea of “bordering” as a potentially project. useful critical term in architectural and design history. Indeed the term may open up new avenues of research by taking into account both material and conceptual infrastructures related to the production of “nations.” Nations are not as fixed as their borders might suggest; they are lived entities, continually remade culturally and socially, as cultural theorist Homi Bhabha asserts with his notion of nation as narration, as built on a dialect- ical tension between the material objects of nation—including architecture—and accompanying narratives.2 Nation is thus conceived as an imaginative yet material process. But what is an architecture of bordering (or borders)? Initially we might think of the architecture at international boundaries, including customs build- ings and the infrastructures of mobil- ity (highways, bridges, tunnels, etc.) or immobility (walls, spaces for detainment of suspected criminals or terrorists, etc.). -

The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock

Transoceanic Canada: The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock by Matthew Hiebert B.A., The University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A., The University of Amsterdam, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) The University Of British Columbia (Vancouver) August 2013 c Matthew Hiebert, 2013 ABSTRACT Through a critical examination of his oeuvre in relation to his transoceanic geographical and intellectual mobility, this dissertation argues that George Woodcock (1912-1995) articulates and applies a normative and methodological approach I term “regional cosmopolitanism.” I trace the development of this philosophy from its germination in London’s thirties and forties, when Woodcock drifted from the poetics of the “Auden generation” towards the anti-imperialism of Mahatma Gandhi and the anarchist aesthetic modernism of Sir Herbert Read. I show how these connected influences—and those also of Mulk Raj Anand, Marie-Louise Berneri, Prince Peter Kropotkin, George Orwell, and French Surrealism—affected Woodcock’s critical engagements via print and radio with the Canadian cultural landscape of the Cold War and its concurrent countercultural long sixties. Woodcock’s dynamic and dialectical understanding of the relationship between literature and society produced a key intervention in the development of Canadian literature and its critical study leading up to the establishment of the Canada Council and the groundbreaking journal Canadian Literature. Through his research and travels in India—where he established relations with the exiled Dalai Lama and major figures of an independent English Indian literature—Woodcock relinquished the universalism of his modernist heritage in practising, as I show, a postcolonial and postmodern situated critical cosmopolitanism that advocates globally relevant regional culture as the interplay of various traditions shaped by specific geographies. -

11111 I Remember Canada

Canadap2.doc 13-12-00 I REMEMBER CANADA ________________________________________ A Book for a Musical Play in Two Acts By Roy LaBerge Copyright (c) 1997 by Roy LaBerge #410-173 Cooper St.. Ottawa ON K2P 0E9 11111 2 Canada [email protected] . Dramatis Personnae The Professor an articulate woman academic Ambrose Smith a feisty senior citizen Six (or more) actors portraying or presenting songs or activities identified with: 1920s primary school children A 1920s school teacher Jazz age singers and dancers Reginald Fessenden A 16-year-old lumberjack Alan Plaunt Graham Spry Fred Astaire Ginger Rogers Guy Lombardo and the Lombardo trio Norma Locke MacKenzie King Canadian servicemen and civilian women Canadian servicewomen The Happy Gang Winston Churchill Hong King prisoner of war A Royal Canadian Medical Corps nurse John Pratt A Senior Non-Commissioned Officer A Canadian naval rating Bill Haley The Everly Brothers Elvis Presley Charley Chamberlain Marg Osborne Anne Murray Ian and Sylvia 3 Gordon Lightfoot Joni Mitchell First contemporary youth Second contemporary youth Other contemporary youths This script includes only minimal stage directions. 4 Overture: Medley of period music) (Professor enters, front curtain, and takes place at lectern left.) PROFESSOR Good evening, ladies and Gentlemen, and welcome to History 3136 - Social History of Canada from 1920 to the Year 2000. I am delighted that so many have registered for this course. In this introductory lecture, I intend to give an overview of some of the major events and issues we will examine during the next sixteen weeks. And I have a surprise in store for you. I am going to share this lecture with a guest, a person whose life spans the period we are studying. -

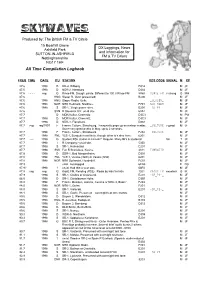

All Time Compilation Logbook by Date/Time

SKYWAVES Produced by: The British FM & TV Circle 15 Boarhill Grove DX Loggings, News Ashfield Park and Information for SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD FM & TV DXers Nottinghamshire NG17 1HF All Time Compilation Logbook FREQ TIME DATE ITU STATION RDS CODE SIGNAL M RP 87.6 1998 D BR-4, Dillberg. D314 M JF 87.6 1998 D NDR-2, Hamburg. D382 M JF 87.6 - - - - reg G Rinse FM, Slough. pirate. Different to 100.3 Rinse FM 8760 RINSE_FM v strong GMH 87.6 HNG Slager R, Gyor (presumed) B206 M JF 87.6 1998 HNG Slager Radio, Gyšr. _SLAGER_ MJF 87.6 1998 NOR NRK Hedmark, Nordhue. F701 NRK_HEDM MJF 87.6 1998 S SR-1, 3 high power sites. E201 -SR_P1-_ MJF 87.6 SVN R Slovenia 202, un-id site. 63A2 M JF 87.7 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz D3C3 M PW 87.7 1998 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz. D3C3 M JF 87.7 1998 D NDR-4, Flensburg. D384 M JF 87.7 reg reg/1997 F France Culture, Strasbourg. Frequently pops up on meteor scatter. _CULTURE v good M JF Some very good peaks in May, up to 2 seconds. 87.7 1998 F France Culture, Strasbourg. F202 _CULTURE MJF 87.7 1998 FNL YLE-1, Eurajoki most likely, though other txÕs also here. 6201 M JF 87.7 ---- 1998 G Student RSL station in Lincoln? Regular. Many ID's & students! fair T JF 87.7 1998 I R Company? un-id site. 5350 M JF 87.7 1998 S SR-1, Halmastad. E201 M JF 87.7 1998 SVK Fun R Bratislava, Kosice. -

Migration, Freedom and Enslavement in the Revolutionary Atlantic: the Bahamas, 1783–C

Migration, Freedom and Enslavement in the Revolutionary Atlantic: The Bahamas, 1783–c. 1800 Paul Daniel Shirley October 2011 UCL PhD thesis 1 I, Paul Daniel Shirley, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: _____________________________ (Paul Daniel Shirley) 2 Abstract This thesis examines the impact of revolution upon slavery in the Atlantic world, focusing upon the period of profound and unprecedented change and conflict in the Bahamas during the final decades of the eighteenth century. It argues that the Bahamian experience can only be satisfactorily understood with reference to the revolutionary upheavals that were transforming the larger Atlantic world in those years. From 1783, the arrival of black and white migrants displaced by the American Revolution resulted in quantitative and qualitative social, economic and political transformation in the Bahamas. The thesis assesses the nature and significance of the sudden demographic shift to a non-white majority in the archipelago, the development of many hitherto unsettled islands, and efforts to construct a cotton-based plantation economy. It also traces the trajectory and dynamics of the complex struggles that ensued from these changes. During the 1780s, émigré Loyalist slaveholders from the American South, intent on establishing a Bahamian plantocracy, confronted not only non-white Bahamians exploring enlarged possibilities for greater control over their own lives, but also an existing white population determined to defend their own interests, and a belligerent governor with a penchant for idiosyncratic antislavery initiatives. In the 1790s, a potentially explosive situation was inflamed still further as a new wave of war and revolution engulfed the Atlantic. -

The Canadian Pacifie Railway's Photographie Advertising and the Travels of Frank Randall Clarke, 1920-1929

The Layout of the Land; the Canadian Pacifie Railway's photographie advertising and the travels of Frank Randall Clarke, 1920-1929. Anne Lynn Becker Department of Art History and Communications Studies McGill University, Montreal August 2005 A thesis suhtnitted to McGill University in partial fulfillnent of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Anne Lynn Becker, 2005 1 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-22587-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-22587-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Community Radio, Television and Newspapers

Carleton University, Ottawa March 2 - 4 , 2017 The role of multilingual radio stations in the development of Canadian society Elena Kaliberda, Carleton University Conference Sponsor(s): Partners: Faculty of Public Affairs Presenting sponsor: Version / Deposit Date: 2017-06-15 Visions for Canada in 2042 Media, Society and Inclusion in Canada: Past, Present and Future March 4th, 2017 The role of multilingual radio stations in the development of Canadian society Elena Kaliberda PhD Candidate School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University Producer and Host, the Russian program at CHIN Radio Ottawa, Media Expert Content Introduction 1. Radio in Canada: Past 2. Radio in Canada: Present 3. Radio in Canada: Future Conclusion 2 Introduction Radio in Canada, in Europe and worldwide plays an important role in informing the public. The development of multicultural radio is a Canadian phenomenon. The present study is mostly devoted to the status and development of multicultural radio in Canada. This presentation looks at only one type of media which is radio. 3 The main research question Radio in Canada: Past, Present, Future. What is the role of multilingual radio in Canada in 2042? 4 The hypothesis The main hypothesis is that the multilingual radio is still the most reliable source of information for many multilingual Canadians. The likely hypothesis for a larger research question will be: the multilingual radio will be the most reliable source of information for Canadian society until 2042. This study makes use of a literature review on radio, statistic data, research interviews, qualitative methods of research. 5 I. Radio in Canada: Past The first radio in Canada was created in 1921 to listen to American stations. -

Index to Archivaria Numbers 1 to 54, 1975–2002

Index to Archivaria Numbers 1 to 54, 1975–2002 Index by bookmark: editing & indexing AAAC. See Archival Association of Atlantic Canada AACR2. See Anglo American Cataloguing Rules, 2d ed. AAQ. See Association des archivistes du Québec Abdication Crisis, The: Are Archivists Giving Up Their Cultural Responsibil- ity?, 40:173–81 Abella, Irving Oral History and the Canadian Labour Movement, 4:115–121 Abiding Conviction, An: Maritime Baptists and Their World (review article), 30:114–17 Aboriginal archives documentary approach, 33:117–24 Métis archive project, 8:154–57 See also Aboriginal peoples; Aboriginal records Aboriginal peoples bibliography, archival sources, Yukon (book review), 28:185 clothing traditions (exhibition review), 40:243–45 Hudson’s Bay Company fur trade (review article), 12:121–26 trade, pre-1763 (book review), 8:186–87 Indian Affairs administration (book review), 25:127–30 land claims archives and, 9:15–32 research handbook (book review), 16:169–71 ledger drawings (exhibition review), 40:239–42 literature by (book review), 18:281–84 missionaries and, since 1534, Canada (book review), 21:237–39 New Zealand Maori and archives, reclaiming the past, 52:26–46 4 Archivaria 56 Northwest Coast artifacts (book review), 23:161–64 and British Navy (book review), 21:252–53 treaties historical evidence (review article), 53:122–29 Split Lake Indians, 17:261–65 and White relations (book review), 4:245–47 in World War I (book review), 48:223–27 See also Aboriginal archives; Aboriginal records; names of specific Native groups Aboriginal -

Invisible Hands in the Winter Garden: Power, Politics, and Florida’S Bahamian Farmworkers in the Twentieth Century

INVISIBLE HANDS IN THE WINTER GARDEN: POWER, POLITICS, AND FLORIDA’S BAHAMIAN FARMWORKERS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY By ERIN L. CONLIN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Erin L. Conlin To my parents, Joe and Judy Conlin ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank the members of my supervisory committee: William A. Link, Elizabeth Dale, Maria Stoilkova, Paul Ortiz, and most particularly, Joseph Spillane, for their help and support on this endeavor. Joe is the quintessential mentor and advisor—thoughtful, kind, patient and dedicated. His tireless support throughout this project—and graduate school more broadly— has been invaluable. Joe’s readings and re-readings, criticisms and suggestions, have sharpened my arguments and clarified my thinking. Any success is thanks to him; any shortcomings are solely my own. Over the years I’ve also had the pleasure of getting to know Jennifer, Maggie, and Lily Spillane. I appreciate their welcoming me into their home and family. Speaking of my UF family, I would be remiss if I did not thank the Wise family, Jessica Harland-Jacobs, Matt, Jeremy, and Alexandra Jacobs, as well as Jack Davis, and Sonya and Willa Rudenstien, for their support over the past few years. It was a pleasure getting to know each of you and becoming a part of your families. I also want to thank Allison Fredette, William Hicks, Johanna Mellis, Greg Mason, Ashley Kerr, Taylor Patterson, Rachel Rothstein, Brian Miller, and many others at the University of Florida. -

Dreams of a Tropical Canada: Race, Nation, and Canadian Aspirations in the Caribbean Basin, 1883-1919

Dreams of a Tropical Canada: Race, Nation, and Canadian Aspirations in the Caribbean Basin, 1883-1919 by Paula Pears Hastings Department of History Duke University Date: _________________________ Approved: ______________________________ John Herd Thompson, Supervisor ______________________________ Susan Thorne ______________________________ D. Barry Gaspar ______________________________ Philip J. Stern Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Dreams of a Tropical Canada: Race, Nation, and Canadian Aspirations in the Caribbean Basin, 1883-1919 by Paula Pears Hastings Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John Herd Thompson, Supervisor ___________________________ Susan Thorne ___________________________ D. Barry Gaspar ___________________________ Philip J. Stern An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Paula Pears Hastings 2010 Abstract Dreams of a “tropical Canada” that included the West Indies occupied the thoughts of many Canadians over a period spanning nearly forty years. From the expansionist fever of the late nineteenth century to the redistribution of German territories immediately following the First World War, Canadians of varying backgrounds campaigned vigorously for Canada-West Indies union. Their efforts generated a transatlantic discourse that raised larger questions about Canada’s national trajectory, imperial organization, and the state of Britain’s Empire in the twentieth century. This dissertation explores the key ideas, tensions, and contradictions that shaped the union discourse over time. Race, nation and empire were central to this discourse. -

A History of the Regulation of Religion in the Canadian Public Square. By

REMOTE CONTROL: A History of the Regulation of Religion in the Canadian Public Square. by Norman James Fennema BA., University of Alberta, 1990 BA. Hon., University of Alberta, 1991 MA., University of Victoria, 1996 A dissertation submitted in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of History We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard. Dr. Ian MaePherson, Supervisor , (Department of History) Dr. I^nne Marks, Departmental Member (Department of History) Dr. Brian Dippie, Departmental Member (Department of History) Dr. John McLaren, Outside Member (Faculty of Law) Dr. DaiddMarshall, External Examiner (Depe&tment of History, University of Calgary) © Norman Fermema, 2003 All rights reserved. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the permission of the author. Supervisor; Dr. Ian MaePherson Abstract The modem Canadian state is secular, but it is not a neutral state. It is a liberal democracy in which the prevailing value system has shifted. The shift has been from a culture in which a commonly held religion was accorded a special place in the development of law and custom, to a culture in which religious pluralism is recognized and an institutionalized secularism obtains. The assumption would be that this would betoken a new tolerance for diversity, and in some ways it does. In other ways, the modem state behaves with an understanding of pluralism that is just as consensus oriented as the Protestant Culture that dominated in Canada until the middle of the twentieth century, and with the same illiberal tendencies. In historical terms, the effect that can be charted is one of repeating hegemonies, where respect for freedom of conscience or religion remains an incomplete ideal. -

Radio Digest, 1929-1930

RADIO in the ^loyd Gibbons NEXT WAR Thirty'Five cyTLarch Cents "MLLE. YVONNE" FL, PARIS, FRANCE Jackson Gregory New Laws for Old Beginning Serial, Thirteen and I Frederick R, Bechdolt The Girl in Gray Mfcigy and c foliOMi® eattire — Studebaker Commander Eight Brougham, for five . six wire wheels and trunk standard equipment JLhese Champion Rights Are Seasoned Eights! The greatest world and international records, and more American stock car records than all other makes of cars combined, bear wit- ness to the proved speed and endurance of Studebaker's smart new Eights. Leadership among all the eights of the world has come swiftly and grown more pronounced. Explain this as you will champion performance, moderate cost, or forward style which achieves true beauty—such leader- ship is the finest testimony of public confidence in Studebaker's 78 years of quality manufacture. STUDEBAKER Builder of (champions RADIO DIGEST Get all the best electric refrigerator features in this new WILLIAMS ICE-O-MATIC Too many electric refrigerators have been sold on the appeal of some one mechanical feature. You are rightly entitled to all the bestfeatures when investing your money. This advanced new Williams Ice-O-Matic com- bines—fortheveryfirsttime— the 15 most important characteristics ofAmerican and European makes. Williams Ice-O-Matic is designed for the womanwho is too busy to be bothered with mechanical details. It is amazingly simple, completely quiet, and virtually as inexpensive to operate as electric light. This great household convenience liter- ally pays for itself by the food it saves. In winter or summer, Ice-O-Matic protects your family's health by the safely low tem- perature in its roomy storage space.