A History of the Regulation of Religion in the Canadian Public Square. By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Helena Chester the Discursive Construction of Freedom in The

The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society Helena Chester Diploma of Teaching (Early Childhood): Riverina – Murray Institute of Higher Education Graduate Diploma of Education (Special Education): Victoria College. Master of Education (Honours): University of New England Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Charles Darwin University, Darwin. October 2018 Certification I certify that the substance of this dissertation has not already been submitted for any degree and is not currently being submitted for any other degree or qualification. I certify that any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 4 Dedication ............................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Abstract ..................................................................................................................... 6 Keywords .............................................................................................................................. 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Chapter 1: The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society ................... 9 The Freedom Claim in the Watchtower Society ............................................................. -

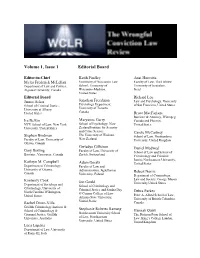

Volume 1, Issue 1 Editorial Board

Volume 1, Issue 1 Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Keith Findley Anat Horovitz Myles Frederick McLellan University of Wisconsin Law Faculty of Law, The Hebrew Department of Law and Politics, School, University of University of Jerusalem, Algoma University, Canada Wisconsin-Madison, Israel United States Editorial Board Richard Leo James Acker Jonathan Freedman Law and Psychology, University School of Criminal Justice, Psychology Department, of San Francisco, United States University at Albany, University of Toronto, United States Canada Bruce MacFarlane Barrister & Attorney, Winnipeg, Ira Belkin Maryanne Garry Canada and Phoenix, NYU School of Law, New York School of Psychology, New United States University, United States Zealand Institute for Security and Crime Science Carole McCartney Stephen Bindman The University of Waikato, School of Law, Northumbria Faculty of Law, University of New Zealand University, United Kingdom Ottawa, Canada Gwladys Gilliéron Daniel Medwed Gary Botting Faculty of Law, University of School of Law and School of Barrister, Vancouver, Canada Zurich, Switzerland Criminology and Criminal Justice Northeastern University, Kathryn M. Campbell Adam Gorski United States Department of Criminology, Faculty of Law and University of Ottawa, Administration, Jagiellonian Robert Norris Canada University, Poland Department of Criminology, Law and Society, George Mason Kimberly Cook Jon Gould Department of Sociology and University,United States School of Criminology and Criminology, University of Criminal Justice and Sandra Day -

To Download the 2021 Annual Meeting Final Program!

Final Program JULY 6 - 9, 2021 | BOSTON, MA MARRIOTT COPLEY PLACE VIRTUAL OPTION AVAILABLE NAVIGATING THE FUTURE FOR REPRODUCTIVE SCIENCE Society for Reproductive Investigation 68th Annual Scientific Meeting Photo Credit: Kyle Klein Table of Contents Message from the SRI President .............................................................................................................1 2021 Program Committee ......................................................................................................................2 General Meeting Information .................................................................................................................3 Meeting Attendance Code of Conduct Policy ..........................................................................................5 Schedule-at-a-Glance ............................................................................................................................7 Boston Information and Social Events ....................................................................................................8 Exhibitors ...............................................................................................................................................9 Hotel Map ............................................................................................................................................10 Continuing Medical Education Information ..........................................................................................11 Scientific Program -

Gobitis and Barnett: the Flag Salute and the Changing Interpretation of the Constitution Rhenee Clark Swink in Minersville Schoo

72 Gobitis and Barnett: The Flag Salute and the Changing Interpretation of the Constitution Rhenee Clark Swink In Minersville School District vs Gobitis (1940) the United States Supreme Court ruled 8 to1 overturning lower court decisions barring states from implementing compulsory flag salutes. Three years later, the Supreme Court overturned that ruling with a 6 to 3 decision in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). The cases were nearly identical and argued similarly but had different outcomes. How did the landscape of America change so drastically in a three-year period? First, the Supreme Court did not see a danger in the rise of nationalism in the United States or the social impact the ruling would bring. Second, the violence that followed Gobitis decision caused Jehovah’s Witnesses, a pacifist group that was uninvolved in politics, to become more persistent in utilizing the legal system and more vocal concerning persecution of its members. Finally, the Supreme Court was not the same. A change in justices and a shift in the focus of the Court from economic matters to personal liberties created a different political landscape, when West Virginia State Board of Education vs. Barnett reached the Court in 1943. Jehovah’s Witnesses sought to spread their message and seek new members through distribution of the organizations magazines and books, playing recorded phonograph messages from organization leaders, and through public lectures. The group was frequently arrested for selling books without a license. Other areas developed specific ordinances to target Jehovah’s Witnesses. One community in Georgia passed an ordinance that prohibited anyone calling on houses to offer any printed material.47 Jehovah Witnesses trace their origins to a group founded in the late nineteenth century in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. -

Transmitting Nation “Bordering” and the Architecture of the CBC in the 1930S1

e ssaY | essai TransmiTTing naTion “Bordering” and the architecture of the CBC in the 1930s1 Mi ChAeL WiNdOVer holds a doctorate in art > MiChael Windover history from the University of British Columbia. his dissertation was awarded the Phyllis-Lambert Prize and a revised version is forthcoming in a series on urban heritage with the Presses de l’Université du Québec as Art deco: A Mode of ational boundaries are as much con- Mobility. Windover is currently in the School of Nceptual as they are material. They Architecture at McGill University working on his delineate a space of belonging and mark a liminal region of identity production, Social Sciences and humanities research Council and yet are premised on a real, physical of Canada postdoctoral project: “Architectures of location with economic and social impli- radio: Sound design in Canada, 1925-1952.” cations. With this in mind, I introduce This article represents initial output from this the idea of “bordering” as a potentially project. useful critical term in architectural and design history. Indeed the term may open up new avenues of research by taking into account both material and conceptual infrastructures related to the production of “nations.” Nations are not as fixed as their borders might suggest; they are lived entities, continually remade culturally and socially, as cultural theorist Homi Bhabha asserts with his notion of nation as narration, as built on a dialect- ical tension between the material objects of nation—including architecture—and accompanying narratives.2 Nation is thus conceived as an imaginative yet material process. But what is an architecture of bordering (or borders)? Initially we might think of the architecture at international boundaries, including customs build- ings and the infrastructures of mobil- ity (highways, bridges, tunnels, etc.) or immobility (walls, spaces for detainment of suspected criminals or terrorists, etc.). -

The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock

Transoceanic Canada: The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock by Matthew Hiebert B.A., The University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A., The University of Amsterdam, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) The University Of British Columbia (Vancouver) August 2013 c Matthew Hiebert, 2013 ABSTRACT Through a critical examination of his oeuvre in relation to his transoceanic geographical and intellectual mobility, this dissertation argues that George Woodcock (1912-1995) articulates and applies a normative and methodological approach I term “regional cosmopolitanism.” I trace the development of this philosophy from its germination in London’s thirties and forties, when Woodcock drifted from the poetics of the “Auden generation” towards the anti-imperialism of Mahatma Gandhi and the anarchist aesthetic modernism of Sir Herbert Read. I show how these connected influences—and those also of Mulk Raj Anand, Marie-Louise Berneri, Prince Peter Kropotkin, George Orwell, and French Surrealism—affected Woodcock’s critical engagements via print and radio with the Canadian cultural landscape of the Cold War and its concurrent countercultural long sixties. Woodcock’s dynamic and dialectical understanding of the relationship between literature and society produced a key intervention in the development of Canadian literature and its critical study leading up to the establishment of the Canada Council and the groundbreaking journal Canadian Literature. Through his research and travels in India—where he established relations with the exiled Dalai Lama and major figures of an independent English Indian literature—Woodcock relinquished the universalism of his modernist heritage in practising, as I show, a postcolonial and postmodern situated critical cosmopolitanism that advocates globally relevant regional culture as the interplay of various traditions shaped by specific geographies. -

11111 I Remember Canada

Canadap2.doc 13-12-00 I REMEMBER CANADA ________________________________________ A Book for a Musical Play in Two Acts By Roy LaBerge Copyright (c) 1997 by Roy LaBerge #410-173 Cooper St.. Ottawa ON K2P 0E9 11111 2 Canada [email protected] . Dramatis Personnae The Professor an articulate woman academic Ambrose Smith a feisty senior citizen Six (or more) actors portraying or presenting songs or activities identified with: 1920s primary school children A 1920s school teacher Jazz age singers and dancers Reginald Fessenden A 16-year-old lumberjack Alan Plaunt Graham Spry Fred Astaire Ginger Rogers Guy Lombardo and the Lombardo trio Norma Locke MacKenzie King Canadian servicemen and civilian women Canadian servicewomen The Happy Gang Winston Churchill Hong King prisoner of war A Royal Canadian Medical Corps nurse John Pratt A Senior Non-Commissioned Officer A Canadian naval rating Bill Haley The Everly Brothers Elvis Presley Charley Chamberlain Marg Osborne Anne Murray Ian and Sylvia 3 Gordon Lightfoot Joni Mitchell First contemporary youth Second contemporary youth Other contemporary youths This script includes only minimal stage directions. 4 Overture: Medley of period music) (Professor enters, front curtain, and takes place at lectern left.) PROFESSOR Good evening, ladies and Gentlemen, and welcome to History 3136 - Social History of Canada from 1920 to the Year 2000. I am delighted that so many have registered for this course. In this introductory lecture, I intend to give an overview of some of the major events and issues we will examine during the next sixteen weeks. And I have a surprise in store for you. I am going to share this lecture with a guest, a person whose life spans the period we are studying. -

Articles Recollections of West Virginia State Board of Education V. Barnette∗

BARNETTE FINAL 9/25/2007 11:11:19 AM ARTICLES RECOLLECTIONS OF WEST VIRGINIA STATE BOARD OF ∗ EDUCATION V. BARNETTE GREGORY L. PETERSON E. BARRETT PRETTYMAN, JR. SHAWN FRANCIS PETERS BENNETT BOSKEY GATHIE BARNETT EDMONDS MARIE BARNETT SNODGRASS JOHN Q. BARRETT WELCOMING REMARKS GREGORY L. PETERSON† Welcome. The Robert H. Jackson Center exists to preserve and advance the legacy of Justice Jackson through education, events, and exhibitry. Today’s special gathering, featuring the Barnett sisters and the attorney who served during 1943 as the senior law clerk to the Chief Justice of the United States, Harlan Fiske Stone, furthers that mission. During World War II, Gathie and Marie Barnett, along with their parents and other Jehovah’s Witnesses, challenged the constitutionality of compelling school children to pledge allegiance and salute the American flag. Their Supreme Court victory, West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette,1 is now a constitutional law landmark. It is a case in which Justice ∗ These proceedings, cosponsored by the Robert H. Jackson Center and the Supreme Court Historical Society, occurred at the Jackson Center in Jamestown, New York, on April 28, 2006. The following remarks were edited for publication. † Partner, Phillips Lytle LLP and Chair of the Board of Directors, Robert H. Jackson Center, Inc. 1 319 U.S. 624 (1943). During the litigation, courts misspelled the Barnett family surname as “Barnette.” 755 BARNETTE FINAL 9/25/2007 11:11:19 AM 756 ST. JOHN’S LAW REVIEW [Vol. 81:755 Jackson wrote for the Court one of his most eloquent and important opinions during his thirteen years as a Justice. -

THE NEW TIMES "Ye Shall Know the Truth and the Truth Shall Make You Free"

THE NEW TIMES "Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free" Vol. 32, No. 10 OCTOBER 1966 "I personally have never experienced anything like it" CANADIAN PATRIOT ON ANNUAL DINNER Before leaving Australia for South Africa and Rhodesia, Canadian patriot, Mr. Ron Gostick editor of "The Canadian Intelligence Service," and National Director of The Can- adian League of Rights, said that the Annual Dinner of "The New Times," held on Friday, September 16, was the highlight of his Australian tour. Mr. Gostick said that he had "never experienced anything like the Annual Dinner. It was a tremendous inspiration to me, a tremen- dous challenge to go back and emulate it" Mr. Gostick was guest of honour at the Annual Dinner, which reached a new height of enthusiasm. A newcomer to the Dinner said at the conclusion that he was "quite overcome" by the balance between good fellowship, dedication, a wonderful feeling of family, and a deep spirituality. In welcoming the guests, the Chairman of New Times Ensign) and the Australian flags provided a vivid splash Ltd., Mr. Edward Rock, said that "We come together of colour. each year to this function to be inspired, and to inspire In proposing the Loyal Toast, the Chairman said that others, including a vast array of supporters who cannot he could not help but be concerned by the fact that for various reasons attend in person." He invited the Her Majesty had apparently not officially sent a message many newcomers to the Dinner, which had a record of sympathy to South Africa following the assassination attendance, "to join completely in the spirit of this func- of Dr. -

La Protection Civile Au Canada, 1938-1988

EN TEMPS DE GUERRE COMME EN TEMPS DE PAIX, GOUVERNEMENT MANQUANT, GOUVERNANCE MANQUÉE : LA PROTECTION CIVILE AU CANADA, 1938-1988 André Lamalice Thèse soumise à la Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales dans le cadre des exigences du programme de doctorat en histoire avec spécialisation en études canadiennes Département d‟histoire Faculté des arts Université d‟Ottawa © André Lamalice, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii RÉSUMÉ À travers l‟étude des cinquante premières années de l‟histoire de la protection civile au Canada, le présent travail discute de la capacité et de la volonté politique de gouvernements nationaux successifs d‟assurer la sécurité de la population en temps de crises et d‟urgences. Cette thèse soutient qu‟à l‟exclusion d‟un bref intermède au plus fort de la Guerre froide, la fonction de protection civile ne parviendra pas à s‟imposer au nombre des priorités de la gouvernance canadienne au cours de cette période. Entre la création administrative d‟un sous-comité sur les précautions contre les raids aériens à la veille de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, qui marque les débuts de la fonction de protection civile au Canada, et l‟adoption en 1988 de la Loi sur la protection civile, un demi-siècle s‟écoule. L‟histoire de cette fonction se développe en réaction à l‟évolution du contexte international et au gré des impératifs politiques, économiques et sociaux nationaux qui marquent la seconde moitié du XXe siècle. Sa généalogie emprunte à la défense nationale à la fois le vocabulaire et la structure. Longtemps confondue dans la forme et dans le fond à la défense civile, la protection civile en arrive tard dans le siècle à se défaire de ses origines imposées et à se forger une personnalité propre orientée vers la gestion des urgences. -

609 the History of the Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Argument Phenomenon in Canada I. Introduction

THE ORGANIZED PSEUDOLEGAL COMMERCIAL ARGUMENT PHENOMENON 609 THE HISTORY OF THE ORGANIZED PSEUDOLEGAL COMMERCIAL ARGUMENT PHENOMENON IN CANADA DONALD J. NETOLITZKY* This article discusses the history of the poorly understood Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Arguments (OPCA) phenomena. Drawing from various reported and unreported sources, the author begins his review in the 1950s with two distinct pseudolegal traditions that evolved separately in both the United States and Canada. Focusing on the prominent members of each era of the OPCA movement, the author explains in depth the concepts behind the movement and what it means for the legal system in Canada today. The article culminates with an analysis of the current OPCA groups and how Canadian courts should respond to future OPCA litigants, while also giving reasons as to why it is important for Canadians to take notice of this movement due to potential security risks. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 610 II. TWO SEPARATE PSEUDOLEGAL TRADITIONS ...................... 613 III. THE PRE-DETAXERS ......................................... 613 IV. THE DETAXER MOVEMENT ................................... 616 A. THE US INFLUENCE: WARMAN, KYBURZ, MULJIANI ............ 617 B. THE PRE-DETAXERS’ SUCCESSORS: BUTTERFIELD, WATSON, MCMORDIE, CANADIAN DETAX GROUP ............. 618 C. THE DETAXER SCHOLAR: DAVID KEVIN LINDSAY .............. 620 D. ONTARIO GURUS: KENNEDY, LAVIGNE ...................... 621 E. ABORIGINAL DETAXER: AGECOUTAY, A.K.A. KING KANEEKANEET