Reading Behind the Lines: Archiving the Canadian News Media Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bchn 1999 Spring.Pdf

British Columbia Historical Federation ORGANIzED 31 OcToBER, 1922 MEMBER SOCIETIES ALBEIUsII DIsTRIcT HISTORICAL SOCIETY NANAIM0 HIsTomcL SoCIE] The British Columbia Box 284 P0 Box 933, STATIoN A Historical Federation is NANAIM0 9R 5N2 PORT ALBERNI BC V an umbrella organization 9Y 7M7 NIC0LA VALLEY MUSuEM & ARCHIvEs BC V embracing regional ALDER GROVE HERITAGE SOCIETY P0 Box 1262, MERRITT BC ViK jB8 societies. 3190 - 271 STREET NORTH SHORE HISTORICAL SOCIETY ALDERGR0vE, BC V4W 3H7 1541 MERLYNN CRESCENT Questions about ANDERSON LiviE HISTORIcAL SOCIETY N0RTHVANC0uvER BC V7J 2X9 membership and Box 40, D’ARCY BC VoN iLo NORTH SHusWA.p HISTORICAL SOCIETY affiliation of societies should be directed ARRow LAxs HIsToRIcAL SOCIETY Box 317, CELI5TA BC VoE iLo to Nancy M. Peter, RR#i, SITE iC, C0MP 27, PRINCEToN & DISTRICT MUSEUM & ARCHIVES Membership Secretary, NAxuSP BC VoG iRo Box 281, PRINCETON BC VoX iWo BC Historical Federation, ATLIN HISTORICAL SocIErY QUALICUM BEACH HIsT. & MUSEUM SocIErY #7—5400 Patterson Box iii, ATUN BC VoW LAO 587 BCH ROAD Avenue, Burnaby, QuAuCuM BEACH V9K i BOuNDALY HIsToRIcAL SOCIETY BC K’ BC V5H2M5 Box 58o SAT..T SPRING ISLAND HISTORICAL SoCwrY GIuD FORKS BC VoH i Ho 129 MCPHILuP5 AvENuE B0wEN ISLAND HISTORIANS SAri SPRING ISLAND BC V8K 2T6 Box 97 SIDNEY & NoRTH SAANICH HISTORICAL SOC. B0wEN ISLAND BC VoN iGo 10840 INNWOOD RD. BuRNALY HISTORICAL SOCIETY NORTH SAANICH BC V8L 5H9 6501 DEER LAICE AVENUE, SILvERY SLOc HISTORICAL SOCIETY BuRNABY BC VG 3T6 Box 301, NEW DENVER BC VoG iSo CHEPvIAINUS VALLEY HIsTOIUCAL SoCIETY SuluEY HIST0IucAL SOCIETY Box 172 Box 34003 17790 #10 HWY. -

Hamilton's Heritage Volume 5

HAMILTON’S HERITAGE 5 0 0 2 e n u Volume 5 J Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act Hamilton Planning and Development Department Development and Real Estate Division Community Planning and Design Section Whitehern (McQuesten House) HAMILTON’S HERITAGE Hamilton 5 0 0 2 e n u Volume 5 J Old Town Hall Reasons for Designation under Part IV Ancaster of the Ontario Heritage Act Joseph Clark House Glanbrook Webster’s Falls Bridge Flamborough Spera House Stoney Creek The Armoury Dundas Contents Introduction 1 Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the 7 Ontario Heritage Act Former Town of Ancaster 8 Former Town of Dundas 21 Former Town of Flamborough 54 Former Township of Glanbrook 75 Former City of Hamilton (1975 – 2000) 76 Former City of Stoney Creek 155 The City of Hamilton (2001 – present) 172 Contact: Joseph Muller Cultural Heritage Planner Community Planning and Design Section 905-546-2424 ext. 1214 [email protected] Prepared By: David Cuming Natalie Korobaylo Fadi Masoud Joseph Muller June 2004 Hamilton’s Heritage Volume 5: Reasons for Designation Under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act Page 1 INTRODUCTION This Volume is a companion document to Volume 1: List of Designated Properties and Heritage Conservation Easements under the Ontario Heritage Act, first issued in August 2002 by the City of Hamilton. Volume 1 comprised a simple listing of heritage properties that had been designated by municipal by-law under Parts IV or V of the Ontario Heritage Act since 1975. Volume 1 noted that Part IV designating by-laws are accompanied by “Reasons for Designation” that are registered on title. -

Transmitting Nation “Bordering” and the Architecture of the CBC in the 1930S1

e ssaY | essai TransmiTTing naTion “Bordering” and the architecture of the CBC in the 1930s1 Mi ChAeL WiNdOVer holds a doctorate in art > MiChael Windover history from the University of British Columbia. his dissertation was awarded the Phyllis-Lambert Prize and a revised version is forthcoming in a series on urban heritage with the Presses de l’Université du Québec as Art deco: A Mode of ational boundaries are as much con- Mobility. Windover is currently in the School of Nceptual as they are material. They Architecture at McGill University working on his delineate a space of belonging and mark a liminal region of identity production, Social Sciences and humanities research Council and yet are premised on a real, physical of Canada postdoctoral project: “Architectures of location with economic and social impli- radio: Sound design in Canada, 1925-1952.” cations. With this in mind, I introduce This article represents initial output from this the idea of “bordering” as a potentially project. useful critical term in architectural and design history. Indeed the term may open up new avenues of research by taking into account both material and conceptual infrastructures related to the production of “nations.” Nations are not as fixed as their borders might suggest; they are lived entities, continually remade culturally and socially, as cultural theorist Homi Bhabha asserts with his notion of nation as narration, as built on a dialect- ical tension between the material objects of nation—including architecture—and accompanying narratives.2 Nation is thus conceived as an imaginative yet material process. But what is an architecture of bordering (or borders)? Initially we might think of the architecture at international boundaries, including customs build- ings and the infrastructures of mobil- ity (highways, bridges, tunnels, etc.) or immobility (walls, spaces for detainment of suspected criminals or terrorists, etc.). -

The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock

Transoceanic Canada: The Regional Cosmopolitanism of George Woodcock by Matthew Hiebert B.A., The University of Winnipeg, 1997 M.A., The University of Amsterdam, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) The University Of British Columbia (Vancouver) August 2013 c Matthew Hiebert, 2013 ABSTRACT Through a critical examination of his oeuvre in relation to his transoceanic geographical and intellectual mobility, this dissertation argues that George Woodcock (1912-1995) articulates and applies a normative and methodological approach I term “regional cosmopolitanism.” I trace the development of this philosophy from its germination in London’s thirties and forties, when Woodcock drifted from the poetics of the “Auden generation” towards the anti-imperialism of Mahatma Gandhi and the anarchist aesthetic modernism of Sir Herbert Read. I show how these connected influences—and those also of Mulk Raj Anand, Marie-Louise Berneri, Prince Peter Kropotkin, George Orwell, and French Surrealism—affected Woodcock’s critical engagements via print and radio with the Canadian cultural landscape of the Cold War and its concurrent countercultural long sixties. Woodcock’s dynamic and dialectical understanding of the relationship between literature and society produced a key intervention in the development of Canadian literature and its critical study leading up to the establishment of the Canada Council and the groundbreaking journal Canadian Literature. Through his research and travels in India—where he established relations with the exiled Dalai Lama and major figures of an independent English Indian literature—Woodcock relinquished the universalism of his modernist heritage in practising, as I show, a postcolonial and postmodern situated critical cosmopolitanism that advocates globally relevant regional culture as the interplay of various traditions shaped by specific geographies. -

11111 I Remember Canada

Canadap2.doc 13-12-00 I REMEMBER CANADA ________________________________________ A Book for a Musical Play in Two Acts By Roy LaBerge Copyright (c) 1997 by Roy LaBerge #410-173 Cooper St.. Ottawa ON K2P 0E9 11111 2 Canada [email protected] . Dramatis Personnae The Professor an articulate woman academic Ambrose Smith a feisty senior citizen Six (or more) actors portraying or presenting songs or activities identified with: 1920s primary school children A 1920s school teacher Jazz age singers and dancers Reginald Fessenden A 16-year-old lumberjack Alan Plaunt Graham Spry Fred Astaire Ginger Rogers Guy Lombardo and the Lombardo trio Norma Locke MacKenzie King Canadian servicemen and civilian women Canadian servicewomen The Happy Gang Winston Churchill Hong King prisoner of war A Royal Canadian Medical Corps nurse John Pratt A Senior Non-Commissioned Officer A Canadian naval rating Bill Haley The Everly Brothers Elvis Presley Charley Chamberlain Marg Osborne Anne Murray Ian and Sylvia 3 Gordon Lightfoot Joni Mitchell First contemporary youth Second contemporary youth Other contemporary youths This script includes only minimal stage directions. 4 Overture: Medley of period music) (Professor enters, front curtain, and takes place at lectern left.) PROFESSOR Good evening, ladies and Gentlemen, and welcome to History 3136 - Social History of Canada from 1920 to the Year 2000. I am delighted that so many have registered for this course. In this introductory lecture, I intend to give an overview of some of the major events and issues we will examine during the next sixteen weeks. And I have a surprise in store for you. I am going to share this lecture with a guest, a person whose life spans the period we are studying. -

The Twentieth Century Marihuana Phenomenon in Canada

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY MARIHUANA PHENOMENON IN CANADA by CLAYTON JAMES MOSHER B.A. University of Toronto 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF - MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Criminology @ Clayton James Mosher 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY December 1985 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Clayton James Mosher Degree: Master of Arts (Criminology) Title of Thesis: The Twentieth Century Marihuana Phenomenon in Canada. Examining Committee: Chairman: F. Douglas Cousineau Asso.ciate Professor, Criminology I, ' , Neil Boyd Senior Supervisor Associate Professor, Criminology Jo E;"""&dor&riminologysistan - T.S. Palys Associate Profes r, Criminology 11.T Bruce K. Alexander External Examiner Professor, Psychology Date PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in raspsnse to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesi s/Project/Extended Essay The Twentieth Century Marihuana Phenomenon Author: - Clayton James Mosher ( name December 12, 1985 (date) ABSTRACT This thesis traces the social and legal history of marihuana from the implementation of the first narcotics legislation in Canada to the present. -

In This Issue

AUGUST 2006 IN THIS ISSUE: GAIL ASPER: BUILDING THE PROJECT OF A LIFETIME MEET THE 2006 DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI AWARD RECIPIENT RESPONDING TO STUDENT RECRUITMENT CHALLENGES CANADA POST AGREEMENT #40063720 POST AGREEMENT CANADA ASPER MBA Excellence. Relevance. Leadership. Our program delivers face-to-face business learning for students who want to combine real-life experience with academic theory, while meeting exacting standards of excellence. MAKE THINGS HAPPEN! Joanne Sam – Asper MBA Student (Finance) For more information about our program call 474-8448 or toll-free 1-800-622-6296 www.umanitoba.ca/asper email: [email protected] Contents ON THE COVER: Gail Asper (BA/81, LLB/84) with a model of the proposed Canadian Museum of Human Rights Photo: Thomas Fricke 5 2006 DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI AWARD Dr. John Foerster, noted physician and researcher, was selected as the recipient of the Distinguished Alumni Award for 2006. 18 CREATING A LEGACY Gail Asper discusses progress on the Human Rights Museum at the Forks, why it has become her passion, and the role that her family plays in her life. 26 RESPONDING TO RECRUITMENT CHALLENGES Executive Director of Enrolment Services Peter Dueck and Winnipeg School Principal Sharon Pekrul discuss factors that influence how high school students make their career choices and how recruitment efforts at the University of Manitoba have reacted to the increasingly competitive post- secondary education environment. IN EVERY ISSUE 3 FEEDBACK 4 ALUMNI ASSOCIATION NEWS 8 EVENTS 10 UNIVERSITY NEWS 17 BRIGHT FUTURES 22 OUR STORIES 24 A CONVERSATION WITH… 28 GIVING BACK 30 THROUGH THE YEARS 36 CAMPUS LIFE CANADA POST AGREEMENT #40063720 REQUEST FOR RETURN! If undeliverable, please return magazine cover to: THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION INC. -

Hamilton Devoted a \Veck to Holding in a Grand Carnival

The City Hall. o/s.Orr the month of August, 1889, the City of Hamilton devoted a \veck to holding IN a Grand Carnival. an accidental By missing of a train at Niagara Falls for New York, a party of English gentlemen, who had been on a tour through Canada and the United States, were induced to take the run of fort}' miles from Niagara to Hamilton, to kill the time while awaiting the departure of the next train going East. So much struck were with the they city, its position, its beauty and resources, that what was intended to be a visit of a few hours became several weeks, and, on their arrival back in England, they wrote to the Secretary of the Hamilton Board of Trade, informing him of the circumstances above recorded, and added: "Of all the we had visited our the places during trip on American Continent, the prettiest, cleanest, healthiest, and best conducted was the City of Hamilton, Canada; and from our inspection of the vast and varied manufacturing industries, its one hundred and seventy factories, with its 14,000 artisans, the large capital invested, and the immense output annually, we concluded it was well named the Birmingham of Canada, and has undoubtedly a great and glorious future before it." The letter finished with the query? "If we saw it by the accidental missing of a train, why not do something to call the attention of the outside world, so that people can go to your City and see for themselves its advantages?" That letter has had much to do with the publishing of this Souvenir. -

Proquest Dissertations

A Changing Sense of Place in Canadian Daily Newspapers: 1894-2005 By Carrie Mersereau Buchanan A.B. Bryn Mawr College M.J. Carleton University, School of Journalism and Communication A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Journalism and Communication Faculty of Public Affairs Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario December 2009 © Carrie Mersereau Buchanan 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Voire r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-67869-5 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-67869-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

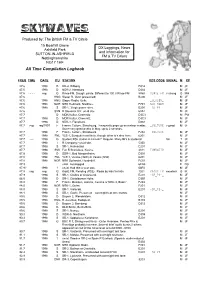

All Time Compilation Logbook by Date/Time

SKYWAVES Produced by: The British FM & TV Circle 15 Boarhill Grove DX Loggings, News Ashfield Park and Information for SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD FM & TV DXers Nottinghamshire NG17 1HF All Time Compilation Logbook FREQ TIME DATE ITU STATION RDS CODE SIGNAL M RP 87.6 1998 D BR-4, Dillberg. D314 M JF 87.6 1998 D NDR-2, Hamburg. D382 M JF 87.6 - - - - reg G Rinse FM, Slough. pirate. Different to 100.3 Rinse FM 8760 RINSE_FM v strong GMH 87.6 HNG Slager R, Gyor (presumed) B206 M JF 87.6 1998 HNG Slager Radio, Gyšr. _SLAGER_ MJF 87.6 1998 NOR NRK Hedmark, Nordhue. F701 NRK_HEDM MJF 87.6 1998 S SR-1, 3 high power sites. E201 -SR_P1-_ MJF 87.6 SVN R Slovenia 202, un-id site. 63A2 M JF 87.7 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz D3C3 M PW 87.7 1998 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz. D3C3 M JF 87.7 1998 D NDR-4, Flensburg. D384 M JF 87.7 reg reg/1997 F France Culture, Strasbourg. Frequently pops up on meteor scatter. _CULTURE v good M JF Some very good peaks in May, up to 2 seconds. 87.7 1998 F France Culture, Strasbourg. F202 _CULTURE MJF 87.7 1998 FNL YLE-1, Eurajoki most likely, though other txÕs also here. 6201 M JF 87.7 ---- 1998 G Student RSL station in Lincoln? Regular. Many ID's & students! fair T JF 87.7 1998 I R Company? un-id site. 5350 M JF 87.7 1998 S SR-1, Halmastad. E201 M JF 87.7 1998 SVK Fun R Bratislava, Kosice. -

Please Insert the Following

CAS NEWSLETTER NO. 107 FALL-SPRING 2009-2010 VOL. LII 1 THE CAS NEWSLETTER CANADIAN ASSOCIATION OF SLAVISTS • ASSOCIATION CANADIENNE DES SLAVISTES ISSN 0381-6133 NO. 107 FALL-SPRING 2009-2010 VOL. LII 12 May 2010 Address by Professor Zinaida Gimpelevich, the President of the Canadian Association of Slavists: Dear colleagues, members, and friends of the Canadian Association of Slavists (CAS), Let me greet you all. I am happy to confirm once again that, thanks to your ongoing support on every level and on every issue, the Canadian Association of Slavists is a solid, healthy, and diverse organization that strongly represents Canadian academia nationally and internationally. We are working truly amicably together. During the last academic year I took part in five international scholarly events and worked closely on your behalf with the Canadian Federation of the Humanities and Social Sciences. Besides my own presentations at these academic venues, I looked intently at other Slavic and non-Slavic academic organizations: their academic and teaching activities, numbers and percentage of academic ranks, students‘ ratio and participation, age groups, and gender. My conclusion is that CAS has a reason to stand tall because our standards and achievements are high. We teach and study to the best of our abilities, and our publications are well received around the globe. Our members receive promotions and get recognition at their own institutions, nationally and internationally. Let me give you just a few examples. Dr. Natalia Pylypiuk has been promoted to the rank of full professor (Congratulations, Natalia!). Dr. David Marples was elected as the President of NAAB (North American Association of Belarusists; Congratulations, David!). -

Doukhobor Problem,” 1899-1999

Spirit Wrestling Identity Conflict and the Canadian “Doukhobor Problem,” 1899-1999 By Ashleigh Brienne Androsoff A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, in the University of Toronto © by Ashleigh Brienne Androsoff, 2011 Spirit Wrestling: Identity Conflict and the Canadian “Doukhobor Problem,” 1899-1999 Ashleigh Brienne Androsoff Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Department of History, University of Toronto, 2011 ABSTRACT At the end of the nineteenth century, Canada sought “desirable” immigrants to “settle” the Northwest. At the same time, nearly eight thousand members of the Dukhobori (commonly transliterated as “Doukhobors” and translated as “Spirit Wrestlers”) sought refuge from escalating religious persecution perpetrated by Russian church and state authorities. Initially, the Doukhobors’ immigration to Canada in 1899 seemed to satisfy the needs of host and newcomer alike. Both parties soon realized, however, that the Doukhobors’ transition would prove more difficult than anticipated. The Doukhobors’ collective memory of persecution negatively influenced their perception of state interventions in their private affairs. In addition, their expectation that they would be able to preserve their ethno-religious identity on their own terms clashed with Canadian expectations that they would soon integrate into the Canadian mainstream. This study focuses on the historical evolution of the “Doukhobor problem” in Russia and in Canada. It argues that