Siege of Suffolk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Mays on Law's Alabama Brigade in the War Between the Union and the Confederacy

Morris Penny, J. Gary Laine. Law's Alabama Brigade in the War Between the Union and the Confederacy. Shippensburg, Penn: White Mane Publishing, 1997. xxi + 458 pp. $37.50, paper, ISBN 978-1-57249-024-6. Reviewed by Thomas D. Mays Published on H-CivWar (August, 1997) Anyone with an interest in the battle of Get‐ number of good maps that trace the path of each tysburg is familiar with the famous stand taken regiment in the fghting. The authors also spice on Little Round Top on the second day by Joshua the narrative with letters from home and interest‐ Chamberlain's 20th Maine. Chamberlain's men ing stories of individual actions in the feld and and Colonel Strong Vincent's Union brigade saved camp, including the story of a duel fought behind the left fank of the Union army and may have in‐ the lines during the siege of Suffolk. fluenced the outcome of the battle. While the leg‐ Laine and Penny begin with a very brief in‐ end of the defenders of Little Round Top contin‐ troduction to the service of Evander McIver Law ues to grow in movies and books, little has been and the regiments that would later make up the written about their opponents on that day, includ‐ brigade. Law, a graduate of the South Carolina ing Evander Law's Alabama Brigade. In the short Military Academy (now known as the Citadel), time the brigade existed (1863-1865), Law's Al‐ had been working as an instructor at a military abamians participated in some of the most des‐ prep school in Alabama when the war began. -

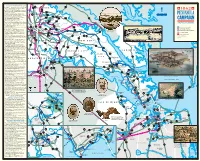

Pen. Map Side

) R ★ MARCH UP THE PENINSULA★ R c a 360 ★ 95 te R Fort Monroe – Largest moat encircled masonry fortifi- m titu 1 Ins o ry A cation in America and an important Union base for t HANOVER o st Hi campaigns throughout the Civil War. o ry P ita P 301 il M P ★ y Fort Wool–Thecompanionfortification to Fort Monroe. m & r A A 2 . The fort was used in operations against Confederate- Enon Church .S g U H f r o held Norfolk in 1861-1862. 606 k y A u s e e t b Yellow Tavern e r ★ r u N Hampton – Confederates burned this port town o s C (J.E.B. Stuart y C to block its use by the Federals on August 7, 1861. k Tot opotomo N c 295 Monument) 643 P i O r • St. John’s Church – This church is the only surviving A C e Old Church K building from the 1861 burning of Hampton. M d Polegreen Church 627 e 606 R • Big Bethel – This June 10, 1861, engagement was r 627 U I F 606 V the first land battle of the Civil War. 628 N 30 E , K R ★ d Bethesda E Monitor-Merrimack Overlook – Scene of the n Y March 9, 1862, Battle of the Ironclads. o Church R I m 615 632 V E ★ Congress and Cumberland Overlook – Scene of the h R c March8,1862, sinking of the USS Cumberland and USS i Cold Harbor R 156 Congress by the ironclad CSS Virginia (Merrimack). -

Connecticut Military and Naval Leaders in the Civil War Connecticut Civil War Centennial Commission •

Cont•Doc l 489 c c f· • 4 THE CONNECTICUT CIVIL WAR CENTENNIAL CONNECTICUT MILITARY AND NAVAL LEADERS IN THE CIVIL WAR CONNECTICUT CIVIL WAR CENTENNIAL COMMISSION • ALBERT D. PUTNAM, Chairman WILLIAM j. FINAN, Vice Chairman WILLIAM j . LoWRY, Secretary • E XEcUTIVE CoMMITTEE ALBERT D. PuTNAM .................... ............................ Ha·rtford WILLIAM j. FINAN ................................................ Woodmont WILLIAM j. LOWRY .............................................. Wethers field BENEDicT M. HoLDEN, jR• ................................ West l!artfortl EDWARD j. LoNERGAN ................................................ Hartford HAMILToN BAsso ........................................ ............ Westport VAN WYcK BRooKs .......... .................................. Bridgewater CHARLES A. BucK ................. ........................... West Hartford j. DoYLE DEWITT .... ............ .. ...... ............ .... .... West Hartford RoBERT EisENBERG ..... .. .................. ... ........................ Stratford ALLAN KELLER .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .... ....... Darien WILLIAM E. MILLs, jR. .......................................... Stamford EDwARD OLsEN ............................ ....... .. ................... Westbrook PROF. RoLLIN G. OsTERWEis ................................ New Havm FRANK E. RAYMOND ................................................ Rowayton ALBERT S. REDWAY ................................ .................... Hamden RoBERT SALE ....................................... -

American Civil War Flags: Documents, Controversy, and Challenges- Harold F

AMERICAN STUDIES jOURNAL Number 48/Winter 2001 The Atnerican Civil War ,.~~-,~.,.... -~~'-'C__ iv_ i__ I _W:.........~r Scho!arship in t4e 21st Cent ea Confere . ISSN: 1433-5239 € 3,00 AMERICAN STUDIES jOURNAL Number 48 Winter 2001 The Atnerican Civil War "Civil War Scholarship in the 21st Century" Selected Conference Proceedings ISSN: 1433-5239 i I Editor's Note Lutherstadt Wittenberg States and the Environment." Since the year 2002 marks November 2001 the five hundredth anniversary of the founding of the University of Wittenberg, the Leucorea, where the Center Dear Readers, for U.S. Studies in based, issue #50 will be devoted to education at the university level in a broad sense. Articles It is with some regret that I must give notice that this on university history, articles on higher education and so present issue of the American Studies Journal is my forth are very welcome. For further information on last as editor. My contract at the Center for U.S. Studies submitting an article, please see the Journal's web site. expires at the end of 2001, so I am returning to the United States to pursue my academic career there. At AUF WIEDERSEHEN, present, no new editor has been found, but the American Embassy in Germany, the agency that finances the Dr. J. Kelly Robison printing costs and some of the transportation costs of Editor the Journal, are seeking a new editor and hope to have one in place shortly. As you are aware, the editing process has been carried out without the assistance of an editorial assistant since November of 2000. -

"4.+?$ Signature and Title of Certifying Official

NPS Fonn 10-900-b OMB No. 10244018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATIONFORM This form is used for documenting multiple pmpcny pups relating to one or several historic wnvxe. Sainsrmctions in How lo Complele the Mul1,ple Property D~mmmlationFonn (National Register Bullnin 16B). Compleveach item by entering the requested information. For addillanal space. use wntinuation shau (Form 10-900-a). Use a rypwiter, word pmarror, or computer to complete dl ivms. A New Submission -Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Llstlng The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources - B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each acsociated historic conk* identifying theme, gmgmphid al and chronological Mod foreach.) The Civil War in Virginia, 1861-1865: Historic and Archaeological Resources - - C. Form Prepared by -- - nameltitle lohn S. Salmon organization Virginia De~artmentof Historic Resourceg smet & number 2801 Kensineton Avenue telephone 804-367-2323 em. 117 city or town -state VA zip code222l As ~ ~ -~~ - ~ ~~~ -~~ An~~~ ~~ sr amended I the duimated authoriw unda the National Hislaic~.~~ R*urvlion of 1%6. ~ hmbv~ ~~ ccrtih. ha this docummfation form , ~ ,~~ mauthe Nhlond Regutn docummunon and xu forth requ~rnncnufor the Istmg of related pmpnia wns~svntw~thihc~mund Rcglster crivna Thu submiu~onmsm ihc prcce4unl ~d pmfes~onalrcqutmnu uc lath in 36 CFR Pan M) ~d the Scsmar) of the Intenoh Standar& Md Guidelina for Alshoology and Historic Revnation. LSa wntinuation shafor additi01w.I wmmmu.) "4.+?$ Signature and title of certifying official I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Virginia's Civil

Virginia’s Civil War A Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A A., Jim, Letters, 1864. 2 items. Photocopies. Mss2A1b. This collection contains photocopies of two letters home from a member of the 30th Virginia Infantry Regiment. The first letter, 11 April 1864, concerns camp life near Kinston, N.C., and an impending advance of a Confederate ironclad on the Neuse River against New Bern, N.C. The second letter, 11 June 1864, includes family news, a description of life in the trenches on Turkey Hill in Henrico County during the battle of Cold Harbor, and speculation on Ulysses S. Grant's strategy. The collection includes typescript copies of both letters. Aaron, David, Letter, 1864. 1 item. Mss2AA753a1. A letter, 10 November 1864, from David Aaron to Dr. Thomas H. Williams of the Confederate Medical Department concerning Durant da Ponte, a reporter from the Richmond Whig, and medical supplies received by the CSS Stonewall. Albright, James W., Diary, 1862–1865. 1 item. Printed copy. Mss5:1AL155:1. Kept by James W. Albright of the 12th Virginia Artillery Battalion, this diary, 26 June 1862–9 April 1865, contains entries concerning the unit's service in the Seven Days' battles, the Suffolk and Petersburg campaigns, and the Appomattox campaign. The diary was printed in the Asheville Gazette News, 29 August 1908. Alexander, Thomas R., Account Book, 1848–1887. 1 volume. Mss5:3AL276:1. Kept by Thomas R. Alexander (d. 1866?), a Prince William County merchant, this account book, 1848–1887, contains a list, 1862, of merchandise confiscated by an unidentified Union cavalry regiment and the 49th New York Infantry Regiment of the Army of the Potomac. -

1 Thompson, S. Millett. Thirteenth Regiment of New Hampshire

Thompson, S. Millett. Thirteenth Regiment of New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865. A Diary Covering Three Years and a Day. New York: Houghton, Mifflin, & Co., 1888. I. JULY 1, 1862, TO DECEMBER 10, 1862. Call for Troops 1 Camp Colby, at Concord N. H, arrival companies, 2 Entertainment, 2 Clothes, 3 Sentinels, 4 Panic about danger to Washington, 5 Camp visitors, 6 March to the Seat of War . 9 Philadelphia refreshment saloon, 9-10 Camp Chase, at Arlington Heights 11 General Casey. 11 Inspection, 12 Munson’s Hill, forts, 13 Upton’s Hill expedition, disease, 15 Fiasco of regiment capturing their own men, 16 Reveille, 19 Camp Casey, at Fairfax Seminary 20 Republicans, Democrats, bounty, 20 Tents, 21 Religious revivalists in the army, 22 First death in camp, typhoid, 23 Disease in camp, 24 Food, 24 Cooking, inspection, 24 Policing camp streets, 25 Cold, exposure, threatened mutiny, 25-26 Thanksgiving, 26 Armor vests, 27 March through Maryland to Fredericksburg .... 27 Fence rails, 28 Purchasing food, foraging, 29 Snow, 30-31 Acquia Creek, 33 Severe cold, 33 Fredericksburg, 34-35 II. DECEMBER 11, 1862, TO FEBRUARY 8, 1863. Battle of Fredericksburg 36 December 11, 36-40 December 12, troops and looting, 41-45 December 13, 45-75 1 December 15, 75-81 More accounts of the battle, 80-85 Smoky Hollow, 86 Dead on the battlefield, stripped, 86 Bombardment of Fredericksburg, 87 Extreme cold, 87-88 Camp opposite Fredericksburg 88 Water, 88 Description of the camp, 89-90 Firewood, 90 Improving winter quarters, 93 Charges -

Union Bands of the Civil War (1862-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 Union Bands of the Civil War (1862-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis. (Volumes I and II). William Alfred Bufkin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Bufkin, William Alfred, "Union Bands of the Civil War (1862-1865): Instrumentation and Score Analysis. (Volumes I and II)." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2523. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2523 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and dius cause a blurred image. -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

The Suffolk Campaign a Case Study

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 12-17-1979 The uS ffolk campaign a case study Brian S. Wills Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Wills, Brian S., "The uS ffolk campaign a case study" (1979). Honors Theses. Paper 756. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SUFFQLK CAMPAIGN A CASE STUDY A thesis presented by Brian Steel Wills to Dr. Frances H. Gregory History Department University of Richmond in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the undergraduate degree of Bachelor of Arts in the subject of History University of Richmond Virginia December 17, 1979 "The Suffolk Campaign: A Case Study" Brian S • vlills "The Suffolk Campaign: A Case Study, 11 covers the Civil 'VJar campaign that began on April 11, 1863 anc ended on Hay 3, 1863 and centered around the small Tidewater Virginia town of Suffolk. Suf- foL~'s strategic prominence was derived from its access to the James River, through a tributary (the Nansemond), and ti-10 major railroads which ran through the town--the Petersburg and Norfolk, and the Roa- noke and Seaboard. The Confederates abandoned the town after NcClel- lan's Peninsula Campaign made their position there untenable. Fed- eral troops quickly entered Suffolk and established it as the first line of defense for Norfolk. -

Regimental History

650 Thirteenth Regiment New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry. (THREE YEARS.) By S. MILLETT THOMPSON, late Second Lieutenant Thirteenth Regiment New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, and Historian of tlie Regiment. THIS i-egiment volunteered under the call of Jul}' i, 1862, for 300,000 men. Gathered personally by their officers to be, two companies each were formed in Rockingham, Hillsborough, and Strafford counties; and one each in Grafton, Merrimack, Carroll, and Coos — all coming into Camp Colby, near Concord, between September 11 and 15. The muster-in of the rank and file was completed on September 20, and of the field and stafl", with the exception of Assistant-Surgeon John Sullivan, on September 23. militarj' outfit, including The colors were received on the afternoon of October 5 ; and at the same time a Springfield rifles, muzzle-loading, calibre 58. Space does not admit fairly of extended mention of individuals. This was at first almost wholly a regiment of native Americans and of New Hampshire's representative young men, many of them lineal descendants of the patriots of 1776 who fought in the Revolution. The average age was a little under twenty-five years, average height five feet and eight inches, and the most were of the dark blonde type. Its companies were fellow townsmen, and its members were in almost every trade and calling — many of whom, too, since the war closed, have gained prominent positions, commercial, professional, and in the Legislatures of States and Nation. The detachments, at the front, of its officers and men, upon special and staff duties, because of their intelligence and eflSciency, were very numerous — exceeding that of any regiment near and associated with it in the service. -

150 Years Ago in the Civil War, April 1863

150 Years Ago in the Civil War, April 1863 April 7 Naval attack on Charleston, South Carolina. The striking force was a fleet of nine ironclad warships of the Union Navy, including seven monitors that were improved versions of the original USS Monitor. A Union Army contingent associated with the attack took no active part in the battle. The ships, under command of Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont, attacked the Confederate defenses near the entrance to Charleston Harbor. Navy Department officials in Washington hoped for a stunning success that would validate a new form of warfare, with armored warships mounting heavy guns reducing traditional forts. Du Pont had been given seven of the Passaic class monitors, the powerful New Ironsides, and the experimental ironclad Keokuk. Other naval operations were sidetracked as their resources were diverted to the attack on Charleston. After a long period of preparation, conditions of tide and visibility allowed the attack to proceed. The slow monitors got into position rather late in the afternoon, and when the tide turned, Du Pont had to suspend the operation. Firing had occupied less than two hours, and the ships had been unable to penetrate even the first line of harbor defense. The fleet retired with one in a sinking condition and most of the others damaged. One sailor in the fleet was killed and twenty-one were wounded, while five Confederate soldiers were killed and eight wounded. After consulting with his captains, Du Pont concluded that his fleet had little chance to succeed. He therefore declined to renew the battle the next morning.