Terrestrial Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest Welcome The following list of recreation activities are avail- able in the Hat Creek Recreation Area. For more detailed information please stop by the Old Station Visitor Information Center, open April - December, or our District Office located in Fall River Mills. Give Hat Creek Rim Overlook - Nearly 1 million years us a call year-around Mon.- Fri. at (530) 336-5521. ago, active faulting gradually dropped a block of Enjoy your visit to this very interesting country. the Earth’s crust (now Hat Creek Valley) 1,000 feet below the top of the Hat Creek Rim, leaving behind Subway Cave - See an underground cave formed this large fault scarp. This fault system is still “alive by flowing lava. Located just off Highway 89, 1/4 and cracking”. mile north of Old Station junction with Highway 44. The lava tube tour is self guided and the walk is A heritage of the Hat Creek area’s past, it offers mag- 1/3 mile long. Bring a lantern or strong flashlight nificent views of Hat Creek Valley, Lassen Peak, as the cave is not lighted. Sturdy Shoes and a light Burney Mountain, and, further away, Mt. Shasta. jacket are advisable. Subway Cave is closed during the winter months. Fault Hat Creek Rim Fault Scarp Vertical movement Hat Creek V Cross Section of a Lava Tube along this fault system alley dropped this block of earth into its present position Spattercone Trail - Walk a nature trail where volca- nic spattercones and other interesting geologic fea- tures may be seen. -

Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Entomofauna Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 0028 Autor(en)/Author(s): Yefremova Zoya A., Ebrahimi Ebrahim, Yegorenkova Ekaterina Artikel/Article: The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) 321-356 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 28, Heft 25: 321-356 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. November 2007 The Subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae in Iran, with description of new species (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) Zoya YEFREMOVA, Ebrahim EBRAHIMI & Ekaterina YEGORENKOVA Abstract This paper reflects the current degree of research of Eulophidae and their hosts in Iran. A list of the species from Iran belonging to the subfamilies Eulophinae, Entedoninae and Tetrastichinae is presented. In the present work 47 species from 22 genera are recorded from Iran. Two species (Cirrospilus scapus sp. nov. and Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) are described as new. A list of 45 host-parasitoid associations in Iran and keys to Iranian species of three genera (Cirrospilus, Diglyphus and Aprostocetus) are included. Zusammenfassung Dieser Artikel zeigt den derzeitigen Untersuchungsstand an eulophiden Wespen und ihrer Wirte im Iran. Eine Liste der für den Iran festgestellten Arten der Unterfamilien Eu- lophinae, Entedoninae und Tetrastichinae wird präsentiert. Mit vorliegender Arbeit werden 47 Arten in 22 Gattungen aus dem Iran nachgewiesen. Zwei neue Arten (Cirrospilus sca- pus sp. nov. und Aprostocetus persicus sp. nov.) werden beschrieben. Eine Liste von 45 Wirts- und Parasitoid-Beziehungen im Iran und ein Schlüssel für 3 Gattungen (Cirro- spilus, Diglyphus und Aprostocetus) sind in der Arbeit enthalten. -

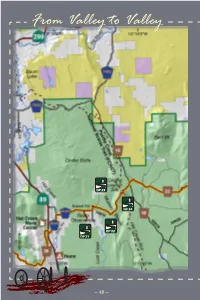

From Valley to Valley

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

Nota Lepidopterologica

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Nota lepidopterologica Jahr/Year: 1992 Band/Volume: Supp_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Baixeras Joaquin, Dominguez Martin Artikel/Article: Remarks on two species of Tortricidae new to Spain (Lepidoptera) 97-102 ©Societas Europaea Lepidopterologica; download unter http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ und www.zobodat.at Proc. VIL Congr. Eur. Lepid., Lunz 3-8.IX.1990 Nota lepid. Supplement No. 4 : 97-102 ; 30.XI.1992 ISSN 0342-7536 Remarks on two species of Tortricidae new to Spain (Lepidoptera) Joaquin Baixeras & Martin Dominguez, Dpt. Biologia Animal, Bio- logia Cellular i Parasitologia, Universität de Valencia, C/Dr. Moliner, 50. E-46100 Burjassot (Valencia), Spain. Summary Some remarks are given on two species of the family Tortricidae in Spain with particular reference to the fauna of the Iberian Mountains : Selania resedana Obr. and Rhyacionia piniana H.-S. are recorded for the first time from the Iberian Peninsula. Information about their distribution, taxonomy and variability is given. Selania resedana (Obraztsov, 1959) Laspeyresia resedana Obraztsov, 1959, Tijdschr. Ent., 102 : 186, 196-197, figs. 44, 45. Locus typicus : Savona (Liguria, Italia). Selania resedana : Danilevsky & Kuznetsov, 1969, Fauna USSR, Lepidop- tera, 5 (1) : 448-449, fig. 322. Kuznetsov, in Medvedev, 1978, Opredelitel Nasek. 4 (1) : 647, 680, figs. 557 (3), 585 (3). Diakonoff, 1983, Fauna of Saudi Arabia 5 : 256-258, figs. 27-32. 1984- Material examined : Calles, 1984-85, 203 <$<$, 55 ÇÇ Porta-Coeli, 85, 48 33, 33 99. Titaguas, 3 33, 1 9. All the localities in the province of Valencia (Spain). -

Pheromone-Based Disruption of Eucosma Sonomana and Rhyacionia Zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Using Aerially Applied Microencapsulated Pheromone1

361 Pheromone-based disruption of Eucosma sonomana and Rhyacionia zozana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) using aerially applied microencapsulated pheromone1 Nancy E. Gillette, John D. Stein, Donald R. Owen, Jeffrey N. Webster, and Sylvia R. Mori Abstract: Two aerial applications of microencapsulated pheromone were conducted on five 20.2 ha plots to disrupt western pine shoot borer (Eucosma sonomana Kearfott) and ponderosa pine tip moth (Rhyacionia zozana (Kearfott); Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) orientation to pheromones and oviposition in ponderosa pine plantations in 2002 and 2004. The first application was made at 29.6 g active ingredient (AI)/ha, and the second at 59.3 g AI/ha. Baited sentinel traps were used to assess disruption of orientation by both moth species toward pheromones, and E. sonomana infes- tation levels were tallied from 2001 to 2004. Treatments disrupted orientation by both species for several weeks, with the first lasting 35 days and the second for 75 days. Both applications reduced infestation by E. sonomana,but the lower application rate provided greater absolute reduction, perhaps because prior infestation levels were higher in 2002 than in 2004. Infestations in treated plots were reduced by two-thirds in both years, suggesting that while increas- ing the application rate may prolong disruption, it may not provide greater proportional efficacy in terms of tree pro- tection. The incidence of infestations even in plots with complete disruption suggests that treatments missed some early emerging females or that mated females immigrated into treated plots; thus operational testing should be timed earlier in the season and should comprise much larger plots. In both years, moths emerged earlier than reported pre- viously, indicating that disruption programs should account for warmer climates in timing of applications. -

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection Cal Fire

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND FIRE PROTECTION CAL FIRE SHASTA – TRINITY UNIT FIRE PLAN Community Wildfire Protection Plan Mike Chuchel Unit Chief Scott McDonald Division Chief – Special Operations Mike Birondo Battalion Chief - Prevention Bureau Kimberly DeSena Fire Captain – Pre Fire Engineering 2008 Shasta – Trinity Unit Fire Plan 1 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................... 4 Unit Fire Plan Assessments and Data Layers................................................ 5 Fire Plan Applications...................................................................................... 6 Community Wildfire Protection Plan............................................................. 6 Unit Fire Plan Responsibilities........................................................................ 6 Key Issues .......................................................................................................... 7 2. STAKEHOLDERS................................................................................. 8 Fire Safe Organizations.................................................................................... 8 Resource Conservation Districts..................................................................... 9 Watershed Contact List ................................................................................... 9 Government Agencies..................................................................................... 13 3. UNIT OVERVIEW ............................................................................. -

Rosten, Lyn, K. True, E. Wiseman, K

National Wild Fish Health Survey California-Nevada Fish Health Center Annual Report for fiscal year 2005 National Wild Fish Health Survey Annual Progress Report FY 2005 Prepared by Lyn Rosten and Kimberly True California-Nevada Fish Health Center Center staff conducted the National Wild Fish Health Survey (NWFHS) in the 2004/2005 fiscal year by collecting fish tissue samples and performing laboratory tests for major fish pathogens in accordance with standardized procedures (NWFHS Laboratory Procedures Manual – 2005, ). This data is entered into a national database and is accessible to the public and resource managers, via the web, and can be viewed at: http://wildfishsurvey.fws.gov/ or http://www.esg.montana.edu/nfhdb/ Kimberly True, Assistant Project Leader Lyn Rosten, Biological Science Technician Eric Wiseman, Fishery Biologist Ken Nichols, Fishery Biologist Scott Foott, Project leader Ron Stone, Fishery Biologist Also assisted with field collections and lab work. 2 Abstract The National Wild Fish Survey (NWFHS), conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Fish Health Centers, assesses the prevalence and distribution of major fish pathogens in wild fish populations. In 2004-2005, the California-Nevada Fish Health Center (Ca-Nv FHC) focused on disease monitoring in the upper Klamath River basin. Pathogens associated with diseased fish in the Klamath River include bacteria (Flavobacterium columnare and motile aeromonad bacteria), digenetic trematode (presumptive Nanophyetus salmincola) and myxozoan parasites (Parvicapsula minibicornis and Ceratomyxa shasta). The incidence of two parasites Ceratomyxa shasta and Parvicapsula minibicornis in juvenile chinook salmon is of special concern. Another focus in 2004-2005 was done in collaboration with Nevada Division of Wildlife’s regional biologists. -

![El Género Rhyacionia Hübner [1825] En La Península Ibérica (Lepidóptera, Tortricidae)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9296/el-g%C3%A9nero-rhyacionia-h%C3%BCbner-1825-en-la-pen%C3%ADnsula-ib%C3%A9rica-lepid%C3%B3ptera-tortricidae-1569296.webp)

El Género Rhyacionia Hübner [1825] En La Península Ibérica (Lepidóptera, Tortricidae)

Bol. San. Veg. Plagas, 22: 711-730, 1996 El género Rhyacionia Hübner [1825] en la Península Ibérica (Lepidóptera, Tortricidae) J. BAIXERAS, M. DOMÍNGUEZ y S. MARTÍNEZ El género Rhyacionia se encuentra representado en la Península Ibérica por seis especies. Cuatro de ellas constituyen uno de los conjuntos más importantes de especies plaga desde el punto de vista forestal, debido a los daños que causan a especies de Pinus L.. Se trata de R. buoliana, R. pinicolana, R. pinivorana y R. duplana. Estas cuatro especies llegan a ser muy comunes en nuestro territorio. Las otras dos especies del género son menos conocidas. R. maritimana, estrechamente emparentada con R. pini- vorana, es una especie común en las zonas más bajas del Sistema Ibérico pero la infor- mación existente sobre ella es todavía escasa. La última especie que se trata, R. pinia- na U.S., es la de menor tamaño y su biología es completamente desconocida, su geni- talia es drásticamente diferente de las del resto del género y su presencia en la Península se ha detectado muy recientemente. A pesar de su importancia económica, continúa existiendo cierta confusión en la dis- tinción de las especies del género. En este artículo se muestran conjuntamente por pri- mera vez las diferencias taxonómicas entre los adultos de estas seis especies, haciendo especial referencia a la diferenciación genital. J. BAIXERAS; M. DOMÍNGUEZ; S. MARTÍNEZ. Departamento de Biología Animal. Universidad de Valencia. Calle Dr. Moliner 50.46100 Burjassot (Valencia) Palabras clave: Tortricidae, Olethreutinae, Eucosmini, Rhyacionia, Península Ibérica. INTRODUCCIÓN La larva de primer estadio mina una acícula y penetra en un brote joven actuando como El género Rhyacionia Hübner, [1825] barrenadora. -

Redalyc.Catalogue of Eucosmini from China (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Zhang, A. H.; Li, H. H. Catalogue of Eucosmini from China (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 33, núm. 131, septiembre, 2005, pp. 265-298 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45513105 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 265 Catalogue of Eucosmini from 9/9/77 12:40 Página 265 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 33 (131), 2005: 265-298 SRLPEF ISSN:0300-5267 Catalogue of Eucosmini from China1 (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) A. H. Zhang & H. H. Li Abstract A total of 231 valid species in 34 genera of Eucosmini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) are included in this catalo- gue. One new synonym, Zeiraphera hohuanshana Kawabe, 1986 syn. n. = Zeiraphera thymelopa (Meyrick, 1936) is established. 28 species are firstly recorded for China. KEY WORDS: Lepidoptera, Tortricidae, Eucosmini, Catalogue, new synonym, China. Catálogo de los Eucosmini de China (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Resumen Se incluyen en este Catálogo un total de 233 especies válidas en 34 géneros de Eucosmini (Lepidoptera: Tor- tricidae). Se establece una nueva sinonimia Zeiraphera hohuanshana Kawabe, 1986 syn. n. = Zeiraphera thymelopa (Meyrick, 1938). 28 especies se citan por primera vez para China. PALABRAS CLAVE: Lepidoptera, Tortricidae, Eucosmini, catálogo, nueva sinonimia, China. Introduction Eucosmini is the second largest tribe of Olethreutinae in Tortricidae, with about 1000 named spe- cies in the world (HORAK, 1999). -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999 United States Renewable Rocky Department of Resources Mountain Agriculture Forest Health Region Management 2 FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION 1997-1999 by The Forest Health Management Staff Edited by Jeri Lyn Harris, Michelle Frank, and Susan Johnson December 2001 USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region Renewable Resources, Forest Health Management P.O. Box 25127 Lakewood, Colorado 80225-5127 Cover: Aerial photograph taken by Robert D. Averill on October 29, 1997, just days after a blowdown event occurred on the Routt National Forest. The picture was taken looking east toward a blowdown area that straddles both the Mt. Zirkel Wilderness and the Routt National Forest. “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternate means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity employer.” Maps in this product are reproduced from geospatial information prepared by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. GIS data and product accuracy may vary. -

Separate Crashes Same Area, Same Morning Injure 4

SERVING EASTERN SHASTA, NORTHERN LASSEN, WESTERN MODOC & EASTERN SISKIYOU COUNTIES 70 Cents Per Copy Vol. 45 No. 22 Burney, California Telephone (530) 335-4533 FAX (530) 335-5335 Internet: im-news.com E-mail: [email protected] AUGUST 13, 2003 What’s Happening Separate crashes same area, Schools Here In Days Ahead spending Mexican dinner same morning injure 4 The Old Station Volunteer Fire again with and Rescue Department will hold a Mexican dinner Satur- fewer cuts day, 5-7 p.m., at the fi re hall. BY MEG FOX The menu will consist of chips With state budget cuts less and salsa, enchilada, Spanish drastic than anticipated and some rice, refried beans, dessert and money saved by cutting costs and beverage. Cost is $6 adults, staff, Fall River Joint Unifi ed School $4 for children ages 10 and District Supt. Eric Newton told the younger. All proceeds benefi t school board that they could afford the fi re department. to do some spending. At the Aug. 6 board meeting, the trustees allocated about $60,000 in Golf tourney unappropriated general fund monies Mayers Intermountain Health- to hire an additional alternative edu- care Foundation will hold its cation teacher to meet increased fi fth annual golf tournament caseloads in that program. Saturday at the Fall River They agreed to spend another Valley Golf and Country Club. $20,000 in unappropriated funds Registration begins at 7:30 (about $42,000 total) to retain the a.m. Tee time is 9 a.m. for the Resource Safety Offi cer through the shotgun start. -

Geologic Map of Lassen Volcanic National Park and Vicinity, California by Michael A

Geologic Map of Lassen Volcanic National Park and Vicinity, California By Michael A. Clynne and L.J. Patrick Muffler Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 2899 Lassen Peak and the Devastated Area Aerial view of Lassen Peak and the proximal Devastated Area looking south. Area with sparse trees marks the paths of the avalanche and debris-flow deposits of May 19–20, 1915 (unitsw9 ) and the pyroclastic-flow and fluid debris-flow deposits of May 22, 1915 (unit pw2) (Clynne and others, 1999; Christiansen and others, 2002). Small dark crags just to right of the summit are remnants of the May 19–20, 1915, lava flow (unitd9 ). The composite dacite dome of Lassen Peak (unit dl, 27±1 ka) dominates the upper part of the view. Lithic pyroclastic-flow deposit (unitpfl ) from partial collapse of the dome of Lassen Peak is exposed in the canyon of the headwaters of Lost Creek in center of view. Ridges flanking central area are glacial moraines (unitQta ) thinly covered by deposits of the 1915 eruption of Lassen Peak (Christiansen and others, 2002). Small permanent snowfield is seen on the left lower slope of Lassen Peak. Area east of the snowfield is the rhyodacite lava flow of Kings Creek (unitrk , 35±1 ka, part of the Eagle Peak sequence). Dacite domes of Bumpass Mountain (unit db, 232±8 ka), Crescent Crater (unit dc, 236±1 ka), hill 8283 (unit d82, 261±5 ka), and Loomis Peak (unit rlm, ~300 ka) are part of the Bumpass sequence. Photograph by Michael A. Clynne. 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S.