The Achomawi from the North American Indian Volume 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Cri'm,Inal Justice

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 1 I . ~ f .:.- IS~?3 INDIAN CRI'M,INAL JUSTICE 11\ PROG;RAM',"::llISPLAY . ,',' 'i\ ',,.' " ,~,~,} '~" .. ',:f,;< .~ i ,,'; , '" r' ,..... ....... .,r___ 74 "'" ~ ..- ..... ~~~- :":~\ i. " ". U.S. DE P ----''''---£iT _,__ .._~.,~~"ftjlX.£~~I.,;.,..,;tI ... ~:~~~", TERIOR BURE AIRS DIVISION OF _--:- .... ~~.;a-NT SERVICES J .... This Reservation criminal justice display is designed to provide information we consider pertinent, to those concerned with Indian criminal justice systems. It is not as complete as we would like it to be since reservation criminal justice is extremely complex and ever changing, to provide all the information necessary to explain the reservation criminal justice system would require a document far more exten::'.J.:ve than this. This publication will undoubtedly change many times in the near future as Indian communities are ever changing and dynamic in their efforts to implement the concept of self-determination and to upgrade their community criminal justice systems. We would like to thank all those persons who contributed to this publication and my special appreciation to Mr. James Cooper, Acting Director of the U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center, Mr •. James Fail and his staff for their excellent work in compiling this information. Chief, Division of Law Enforcement Services ______ ~ __ ---------=.~'~r--~----~w~___ ------------------------------------~'=~--------------~--------~. ~~------ I' - .. Bureau of Indian Affairs Division of Law Enforcement Services U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center Research and Statistical Unit S.UMM.ARY. ~L JUSTICE PROGRAM DISPLAY - JULY 1974 It appears from the attached document that the United States and/or Indian tribes have primary criminal and/or civil jurisdiction on 121 Indian reservations assigned administratively to 60 Agencies in 11 Areas, or the equivalent. -

CMS Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives in California

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives in California Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) staff work with beneficiaries, health care providers, state government, CMS contractors, community groups and others to provide education and address questions in California. American Indians and Alaska Natives If you have questions about CMS programs in relation to American Indians or Alaska Natives: • email the CMS Division of Tribal Affairs at [email protected], or • contact a CMS Native American Contact (NAC). For a list of NAC and their information, visit https://go.cms.gov/NACTAGlist Why enroll in CMS programs? When you sign up for Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or Medicare, the Indian health hospitals and clinics can bill these programs for services provided. Enrolling in these programs brings money into the health care facility, which is then used to hire more staff, pay for new equipment and building renovations, and saves Purchased and Referred Care dollars for other patients. Patients who enroll in CMS programs are not only helping themselves and others, but they’re also supporting their Indian health care hospital and clinics. Assistance in California To contact Indian Health Service in California, contact the California Area at (916) 930–3927. Find information about coverage and Indian health facilities in California. These facilities are shown on the maps in the next pages. Medicare California Department of Insurance 1 (800) 927–4357 www.insurance.ca.gov/0150-seniors/0300healthplans/ Medicaid/Children’s Health Medi-Cal 1 (916) 552–9200 www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal Marketplace Coverage Covered California 1 (800) 300–1506 www.coveredca.com Northern Feather River Tribal Health— Oroville California 2145 5th Ave. -

Pit River and Rock Creek 2012 Summary Report

Pit River and Rock Creek 2012 summary report October 9, 2012 State of California Department of Fish and Wildlife Heritage and Wild Trout Program Prepared by Stephanie Mehalick and Cameron Zuber Introduction Rock Creek, located in northeastern California, is tributary to the Pit River approximately 3.5 miles downstream from Lake Britton (Shasta County; Figure 1). The native fish fauna of the Pit River is similar to the Sacramento River and includes rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss sp.), sculpin (Cottus spp.), hardhead (Mylopharadon conocephalus), Sacramento sucker (Catostomus occidentalis), speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus) and Sacramento pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis; Moyle 2002). In addition, the Pit River supports a wild population of non-native brown trout (Salmo trutta). It is unknown whether the ancestral origins of rainbow trout in the Pit River are redband trout (O. m. stonei) or coastal rainbow trout (O. m. irideus) and for the purposes of this report, we refer to them as rainbow trout. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife Heritage and Wild Trout Program (HWTP) has evaluated the Pit River as a candidate for Wild Trout Water designation since 2008. Wild Trout Waters are those that support self-sustaining wild trout populations, are aesthetically pleasing and environmentally productive, provide adequate catch rates in terms of numbers or size of trout, and are open to public angling (Bloom and Weaver 2008). The HWTP utilizes a phased approach to evaluate designation potential. In 2008, the HWTP conducted Phase 1 initial resource assessments in the Pit River to gather information on species composition, size class structure, habitat types, and catch rates (Weaver and Mehalick 2008). -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

Shasta Lake Unit

Fishing The waters of Shasta Lake provide often congested on summer weekends. Packers Bay, Coee Creek excellent shing opportunities. Popular spots Antlers, and Hirz Bay are recommended alternatives during United States Department of Vicinity Map are located where the major rivers and periods of heavy use. Low water ramps are located at Agriculture Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area streams empty into the lake. Fishing is Jones Valley, Sugarloaf, and Centimudi. Additional prohibited at boat ramps. launching facilities may be available at commercial Trinity Center marinas. Fees are required at all boat launching facilities. Scale: in miles Shasta Unit 0 5 10 Campground and Camping 3 Shasta Caverns Tour The caverns began forming over 250 8GO Information Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity 12 million years ago in the massive limestone of the Gray Rocks Trinity Unit There is a broad spectrum of camping facilities, ranging Trinity Gilman Road visible from Interstate 5. Shasta Caverns are located o the National Recreation Area Lake Lakehead Fenders from the primitive to the luxurious. At the upper end of Ferry Road Shasta Caverns / O’Brien exit #695. The caverns are privately the scale, there are 9 marinas and a number of resorts owned and tours are oered year round. For schedules and oering rental cabins, motel accommodations, and RV Shasta Unit information call (530) 238-2341. I-5 parks and campgrounds with electric hook-ups, swimming 106 pools, and showers. Additional information on Forest 105 O Highway Vehicles The Chappie-Shasta O Highway Vehicle Area is located just below the west side of Shasta Dam and is Service facilities and services oered at private resorts is Shasta Lake available at the Shasta Lake Ranger Station or on the web managed by the Bureau of Land Management. -

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest Welcome The following list of recreation activities are avail- able in the Hat Creek Recreation Area. For more detailed information please stop by the Old Station Visitor Information Center, open April - December, or our District Office located in Fall River Mills. Give Hat Creek Rim Overlook - Nearly 1 million years us a call year-around Mon.- Fri. at (530) 336-5521. ago, active faulting gradually dropped a block of Enjoy your visit to this very interesting country. the Earth’s crust (now Hat Creek Valley) 1,000 feet below the top of the Hat Creek Rim, leaving behind Subway Cave - See an underground cave formed this large fault scarp. This fault system is still “alive by flowing lava. Located just off Highway 89, 1/4 and cracking”. mile north of Old Station junction with Highway 44. The lava tube tour is self guided and the walk is A heritage of the Hat Creek area’s past, it offers mag- 1/3 mile long. Bring a lantern or strong flashlight nificent views of Hat Creek Valley, Lassen Peak, as the cave is not lighted. Sturdy Shoes and a light Burney Mountain, and, further away, Mt. Shasta. jacket are advisable. Subway Cave is closed during the winter months. Fault Hat Creek Rim Fault Scarp Vertical movement Hat Creek V Cross Section of a Lava Tube along this fault system alley dropped this block of earth into its present position Spattercone Trail - Walk a nature trail where volca- nic spattercones and other interesting geologic fea- tures may be seen. -

Aspects of Pit River Phonology

ASPECTS OF PIT RIVER PHONOLOGY Bruce E. Nevin A DISSERTATION in Linguistics Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1998 _____________________________ Supervisor of Dissertation _____________________________ Graduate Group Chairperson iii iv To the Pit River people In memory of Yámá·litwí·daá Dísdí sí·sá·dumá má céá suwí tús dit·é·wi, amxágam táxábáà tól·ím dáx cú wíc stíjéuwí?à Qa ßís ßú wóá dis·i ßuwá·géá ß tyánuwí,á toljana winá·ji·wíní. iii iv Abstract Aspects of Pit River Phonology Bruce Nevin Eugene Buckley Until recently, it has seemed that the Pit River language (“Achumawi”) was reasonably well documented by de Angulo & Freeland (1930), Uldall (1933), and Olmsted (1956, 1957, 1959, 1964, 1966). My own fieldwork in 1970-74 disclosed fundamental inadequacies of these publications, as reported in Nevin (1991). We substantiate this finding, investigate its probable bases, and establish why my own data are not subject to the same difficulties. After this cautionary tale about the perils of restating a published grammar, we define a phonemic representation for utterances in the language and introduce Optimality Theory (OT). We then apply OT to a series of problems in the phonological patterning of the language: features of syllable codas, restrictions and alternations involving voiceless release and aspiration, and reduplicative morphology. Appendix A describes the physiology and phonetics of laryngeal phenomena in Pit River, especially epiglottal articulation that has in the past been improperly described as pharyngeal or involving the tongue radix (the feature RTR). -

From Valley to Valley

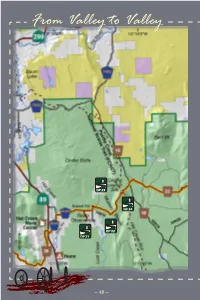

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

Drought and Equity in California

Drought and Equity in California Laura Feinstein, Rapichan Phurisamban, Amanda Ford, Christine Tyler, Ayana Crawford January 2017 Drought and Equity in California January 2017 Lead Authors Laura Feinstein, Senior Research Associate, Pacific Institute Rapichan Phurisamban, Research Associate, Pacific Institute Amanda Ford, Coalition Coordinator, Environmental Justice Coalition for Water Christine Tyler, Water Policy Leadership Intern, Pacific Institute Ayana Crawford, Water Policy Leadership Intern, Pacific Institute Drought and Equity Advisory Committee and Contributing Authors The Drought and Equity Advisory Committee members acted as contributing authors, but all final editorial decisions were made by lead authors. Sara Aminzadeh, Executive Director, California Coastkeeper Alliance Colin Bailey, Executive Director, Environmental Justice Coalition for Water Carolina Balazs, Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley Wendy Broley, Staff Engineer, California Urban Water Agencies Amanda Fencl, PhD Student, University of California, Davis Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior Kelsey Hinton, Program Associate, Community Water Center Gita Kapahi, Director, Office of Public Participation, State Water Resources Control Board Brittani Orona, Environmental Justice and Tribal Affairs Specialist and Native American Studies Doctoral Student, University of California, Davis Brian Pompeii, Lecturer, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Tim Sloane, Executive Director, Institute for Fisheries Resources ISBN-978-1-893790-76-6 © 2017 Pacific Institute. All rights reserved. Pacific Institute 654 13th Street, Preservation Park Oakland, California 94612 Phone: 510.251.1600 | Facsimile: 510.251.2203 www.pacinst.org Cover Photos: Clockwise from top left: NNehring, Debargh, Yykkaa, Marilyn Nieves Designer: Bryan Kring, Kring Design Studio Drought and Equity in California I ABOUT THE PACIFIC INSTITUTE The Pacific Institute envisions a world in which society, the economy, and the environment have the water they need to thrive now and in the future. -

Native American Heritage Commission 40Th Anniversary Gala

“Itu ~(/; W/is ~the ~policy 4of ~the ~state Uwd/;that Native~ Americansll/~ remains ~ ~~~~JwJU~~JJand associated grave goods shall be repatriated.” - California Public Resources Code 5097.991 Table of Contents Event Agenda ....................................................................................................................1 Welcome Letter – Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. ...........................................................2 2016 Native American Day Proclamation ...........................................................................3 Welcome Letter – NAHC Chairperson James Ramos ...................................................... 4 Welcome Letter – NAHC Executive Secretary Cynthia Gomez .........................................5 Keynote Speaker Biography ............................................................................................6 State Capitol Rotunda Displays .......................................................................................7 Native American Heritage Commission’s Mission Statement .............................................8 Tribal People of California Map .......................................................................................13 California Indian Seal ...................................................................................................... 14 The Eighteen Unratifed Treaties of 1851-1852 between the California Indians and the United States Government .................................................................................15 NAHC Timeline -

The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY VOL. 6 NO. 2 THE GEOGRAPHY AND DIALECTS OF THE MIWOK INDIANS. BY S. A. BARRETT. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction.--...--.................-----------------------------------333 Territorial Boundaries ------------------.....--------------------------------344 Dialects ...................................... ..-352 Dialectic Relations ..........-..................................356 Lexical ...6.................. 356 Phonetic ...........3.....5....8......................... 358 Alphabet ...................................--.------------------------------------------------------359 Vocabularies ........3......6....................2..................... 362 Footnotes to Vocabularies .3.6...........................8..................... 368 INTRODUCTION. Of the many linguistic families in California most are con- fined to single areas, but the large Moquelumnan or Miwok family is one of the few exceptions, in that the people speaking its various dialects occupy three distinct areas. These three areas, while actually quite near together, are at considerable distances from one another as compared with the areas occupied by any of the other linguistic families that are separated. The northern of the three Miwok areas, which may for con- venience be called the Northern Coast or Lake area, is situated in the southern extremity of Lake county and just touches, at its northern boundary, the southernmost end of Clear lake. This 334 University of California Publications in Am. Arch. -

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection Cal Fire

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND FIRE PROTECTION CAL FIRE SHASTA – TRINITY UNIT FIRE PLAN Community Wildfire Protection Plan Mike Chuchel Unit Chief Scott McDonald Division Chief – Special Operations Mike Birondo Battalion Chief - Prevention Bureau Kimberly DeSena Fire Captain – Pre Fire Engineering 2008 Shasta – Trinity Unit Fire Plan 1 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................... 4 Unit Fire Plan Assessments and Data Layers................................................ 5 Fire Plan Applications...................................................................................... 6 Community Wildfire Protection Plan............................................................. 6 Unit Fire Plan Responsibilities........................................................................ 6 Key Issues .......................................................................................................... 7 2. STAKEHOLDERS................................................................................. 8 Fire Safe Organizations.................................................................................... 8 Resource Conservation Districts..................................................................... 9 Watershed Contact List ................................................................................... 9 Government Agencies..................................................................................... 13 3. UNIT OVERVIEW .............................................................................