A Celebration of Ut Unum Sint the 25Th Anniversary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesia De Eucharistia on Its Ecumenical Import

Ecumenical & Interfaith Commission: www.melbourne.catholic.org.au/eic Ecclesia de Eucharistia On Its Ecumenical Import By Clint Le Bruyns (Clint Le Bruyns, is an Anglican ecumenist who is currently completing a research project on contemporary Anglican and Protestant perspectives on the Petrine ministry at the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, where he also serves in the faculty of theology as Assistant Lecturer and Research Development Coordinator of the Beyers Naude Centre for Public Theology.) The pope’s latest encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church) – the fourteenth in his 25-year pontificate - was released in Rome on Maundy or Holy Thursday, April 17, 2003.1 Flanked by an introduction (1-10) and conclusion (59-62), the papal letter comprises six critical sections in which the Eucharist is discussed: The Mystery of Faith (11-20); The Eucharist Builds the Church (21-25); The Apostolicity of the Eucharist and of the Church (26-33); The Eucharist and Ecclesial Communion (34-46); The Dignity of the Eucharistic Celebration (47-52); and At the School of Mary, “Woman of the Eucharist” (53-58). Published in English, French, Italian, Spanish, German, Portuguese and Latin, it is a personal, warm, and passionate letter by the current pope on a longstanding theological treasure and dilemma (cf. 8). Like all papal encyclicals it is an internal theological document, bearing the full authority of the Vatican and addressing a matter of grave importance and concern for Roman Catholic faith, life and ministry. But papal texts are no longer merely Roman Catholic in orientation and scope. -

The Holy See

The Holy See VESPERS LITURGY ON THE OCCASION OF THE 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE PROMULGATION OF THE CONCILIAR DECREE "UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO" HOMILY OF JOHN PAUL II Saturday, 13 November 2004 "But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace" (Eph 2: 13ff.).1. With these words from his Letter to the Ephesians the Apostle proclaims that Christ is our peace. We are reconciled in him; we are no longer strangers but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone (cf. Eph 2: 19ff.).We have listened to Paul's words on the occasion of this celebration that sees us gathered in the venerable Basilica built over the Apostle Peter's tomb. I cordially greet those taking part in the ecumenical conference organized for the 40th anniversary of the promulgation of the Decree Unitatis Redintegratio of the Second Vatican Council. I extend my greeting to the Cardinals, Patriarchs and Bishops taking part, to the Fraternal Delegates of the other Churches and Ecclesial Communities, and to the Consultors, guests and collaborators of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I thank you for having carefully examined the meaning of this important Decree and the actual and future prospects of the ecumenical movement. This evening we are gathered here to praise God from whom come every good endowment and every perfect gift (cf. Jas 1: 17), and to thank him for the rich fruit the Decree has yielded with the help of the Holy Spirit during these past 40 years.2. -

Ut Unum Sint

ENCYCLICAL LETTER UT UNUM SINT OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II ON COMMITMENT TO ECUMENISM 25 May 1995 INTRODUCTION 1. Ut unum sint! The call for Christian unity made by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council with such impassioned commitment is finding an ever greater echo in the hearts of believers, especially as the Year 2000 approaches, a year which Christians will celebrate as a sacred Jubilee, the commemoration of the Incarnation of the Son of God, who became man in order to save humanity. The courageous witness of so many martyrs of our century, including members of Churches and Ecclesial Communities not in full communion with the Catholic Church, gives new vigor to the Council’s call and reminds us of our duty to listen to and put into practice its exhortation. These brothers and sisters of ours, united in the selfless offering of their lives for the Kingdom of God, are the most powerful proof that every factor of division can be transcended and overcome in the total gift of self for the sake of the Gospel. Christ calls all his disciples to unity. My earnest desire is to renew this call today, to propose it once more with determination, repeating what I said at the Roman Coliseum on Good Friday 1994, at the end of the meditation on the Via Crucis prepared by my Venerable Brother Bartholomew, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. There I stated that believers in Christ, united in following in the footsteps of the martyrs, cannot remain divided. If they wish truly and effectively to oppose the world’s tendency to reduce to powerlessness the Mystery of Redemption, they must profess together the same truth about the Cross.1 The Cross! An anti-Christian outlook seeks to minimize the Cross, to empty it of its meaning, and to deny that in it man has the source of his new life. -

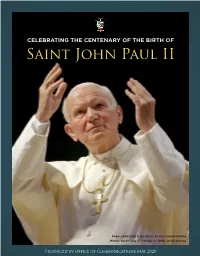

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

The Ecumenical Legacy of Saint John Paul II: a Providential Vision of Christian Division, a Prophetic Vision of Christian Unity

The Ecumenical Legacy of Saint John Paul II: A Providential Vision of Christian Division, a Prophetic Vision of Christian Unity Hyacinthe Destivelle, O.P. Talk for the 2020 Father Val Ambrose McInnes Chair Angelicum Donor Homecoming Twenty–five years ago, on 25 May 1995, on the Feast of the Ascension, Saint John Paul II published his milestone encyclical Ut unum sint on the ecumenical commitment. Thirty years after the end of the Second Vatican Council, he reiterated that the Catholic Church is committed “irrevocably” to following the path of the ecumenical venture (UUS 3) and “embraces with hope the commitment to ecumenism as a duty of the Christian conscience enlightened by faith and guided by love” (UUS 8). The jubilee of the encyclical, which coincides with the centenary of the birth of John Paul II, is an opportunity to enquire into the contribution to ecumenism of the first Slavic 1 pope. Readily recalling that he came from a country with a deep ecumenical tradition, John Paul II liked to repeat that the restoration of Christian unity was “one of the first and major 2 tasks of [his] pontificate”. Not only did John Paul II write the first papal encyclical on ecumenism, in which for the first time a pope invited pastors and theologians of the various churches to seek the forms in which his ministry of unity “may accomplish a service of love recognized by all concerned” (UUS 95), but he accomplished many prophetic gestures: for example, he was the first pope to preach at the Lutheran church in Rome (1983) and to visit countries of Orthodox tradition (Romania and Georgia in 1999, Greece and Ukraine in 2001, Bulgaria in 2002). -

Ecclesia De Eucharistia – on the Criteria for Intercommunion

Le Bruyns, C University of Stellenbosch Ecclesia de Eucharistia – on the criteria for intercommunion ABSTRACT In contemporary ecumenism, papal encyclicals are read and assessed as ecumenical theological statements on matters of grave importance. Ecclesia de Eucharistia, released in April 2003, is penned by John Paul II and concerns itself with the Eucharist and its relationship to the Church. Since the day it was released, various initial reactions from different Christian churches have begun pouring in. Virtually all of these statements highlight what the respective denominations identify as the most critical as well as lamentable section: the pope’s remarks on the longstanding ecumenical discourse on Eucharistic hospitality (or sharing). This article focuses on Ecclesia de Eucharistia for an ecumenical critique of the relevant statements around intercommunion as well as its impact on future ecumenical relations. 1. INTRODUCTION During the afternoon celebration of the Mass of the Lord’s Supper on Maundy (or Holy) Thursday in Rome, April 17, 2003, the current pope signed his latest encyclical letter Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its relationship to the Church). This internal papal document is addressed to “the Bishops, Priests and Deacons, Men and Women in the Consecrated Life and All the Lay Faithful on the Eucharist and Its Relationship to the Church” and has been published to this point in English, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish, French and Portuguese. It is clearly a warm but firm theological statement on the meaning and role of the Eucharist, comprising an introduction (§ 1- 1 10), six chapters (§ 11-58), and a conclusion (§ 59-62). -

The Path from Ut Unum Sintto Receptive Ecumenism

chapter 5 The Path from Ut Unum Sint to Receptive Ecumenism: The Spiritual Roots of Receptive Ecumenism Investigating Receptive Ecumenism’s ancestry leads us now to consider post- Vatican ii influences on its development, namely: Ut Unum Sint, the work of Walter Kasper, and Margaret O’Gara’s ecumenical gift exchange. The path will be followed right up to Receptive Ecumenism’s launch, and will conclude with a summary of Spiritual Ecumenism’s key features. 1 The Groundwork for Receptive Ecumenism in Ut Unum Sint John Paul ii’s 1995 encyclical “Ut Unum Sint: On Commitment to Ecumenism,” is regarded as “the single most important Catholic document pertaining to ec- umenism” since Unitatis Redintegratio.1 It is also a key influence on Receptive Ecumenism. Born Karol Józef Wojtyła (1920–2005), he served as Pope John Paul ii from 1978 until his death. Before becoming Pope, he attended the Second Vatican Council (1962– 1965). Throughout his pontificate, he strongly supported the reforms of Vatican ii and the ecumenical endeavour. His emphasis on the importance of ecumenism characterised his papacy from its beginning.2 He of- ten repeated that the Catholic Church has an “irrevocable” commitment to ec- umenism.3 For John Paul ii, “ecumenism is an organic part” of the church’s “life and work, and consequently must pervade all that she is and does.”4 He worked 1 Murray, “Roman Catholicism and Ecumenism.” 2 Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson, “Introduction,” in Church Unity and the Papal Office: An Ecumenical Dialogue on John Paul II’s Encyclical Ut Unum Sint (That All May Be One), ed. -

Ecumenical Guidelines for the Dioceses of Texas

Ecumenical Guidelines for the Dioceses of Texas Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Sources .................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Worship Services .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Norms of Reciprocity and Collaboration .................................................................................................................... 5 Sharing in Non‐Sacramental Liturgical Worship ...................................................................................................... 6 Ecumenical Services ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 Interfaith Services .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Sharing in God’s Word in Sacred Scripture ................................................................................................................ 7 Sacramental Celebrations ............................................................................................................................................. -

Saint John Paul II (1978-2005)

Saint John Paul II (1978-2005) His Holiness John Paul II (16 Oct. 1978-2 April 2005) was the first Slav and the first non-Italian Pope since Hadrian VI. Karol Wojtyla was born on 18 May 1920 at Wadowice, an industrial town south-west of Krakow, Poland. His father was a retired army lieutenant, to whom he became especially close since his mother died when he was still a small boy. Joining the local primary school at seven, he went at eleven to the state high school, where he proved both an outstanding pupil and a fine sportsman, keen on football, swimming, and canoeing (he was later to take up skiing); he also loved poetry, and showed a particular flair for acting. In 1938 he moved with his father to Krakow where he entered the Jagiellonian University to study Polish language and literature; as a student he was prominent in amateur dramatics, and was admired for his poems. When the Germans occupied Poland in September 1939, the university was forcibly closed down, although an underground network of studies was maintained (as well as an underground theatrical club which he and a friend organised). Thus he continued to study incognito, and also to write poetry. In winter 1940 he was given a labourer’s job in a limestone quarry at Zakrówek, outside Krakow, and in 1941 was transferred to the water- purification department of the Solway factory in Borek Falecki; these experiences were to inspire some of the more memorable of his later poems. In 1942, after his father’s death and after recovering from two near-fatal accidents, he felt the call to the priesthood, began studying theology clandestinely and after the liberation of Poland by the Russian forces in January 1945 was able to rejoin the Jagiellonian University openly. -

Novo Millennio Ineunte of His Holiness Pope John Paul Ii to the Bishops Clergy and Lay Faithful at the Close of the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000

APOSTOLIC LETTER NOVO MILLENNIO INEUNTE OF HIS HOLINESS POPE JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS CLERGY AND LAY FAITHFUL AT THE CLOSE OF THE GREAT JUBILEE OF THE YEAR 2000 To my Brother Bishops, To Priests and Deacons, Men and Women Religious and all the Lay Faithful. 1. At the beginning of the new millennium, and at the close of the Great Jubilee during which we celebrated the two thousandth anniversary of the birth of Jesus and a new stage of the Church's journey begins, our hearts ring out with the words of Jesus when one day, after speaking to the crowds from Simon's boat, he invited the Apostle to "put out into the deep" for a catch: "Duc in altum" (Lk 5:4). Peter and his first companions trusted Christ's words, and cast the nets. "When they had done this, they caught a great number of fish" (Lk 5:6). Duc in altum! These words ring out for us today, and they invite us to remember the past with gratitude, to live the present with enthusiasm and to look forward to the future with confidence: "Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and for ever" (Heb 13:8). The Church's joy was great this year, as she devoted herself to contemplating the face of her Bridegroom and Lord. She became more than ever a pilgrim people, led by him who is the "the great shepherd of the sheep" (Heb 13:20). With extraordinary energy, involving so many of her members, the People of God here in Rome, as well as in Jerusalem and in all the individual local churches, went through the "Holy Door" that is Christ. -

Ii. Teologia W Perspektywie Ekumenii

II. TEOLOGIA W PERSPEKTYWIE EKUMENII Studia Oecumenica 15 (2015) s. 97–122 Sławomir NowoSad Wydział Teologii KUL Non-Catholic Reactions to Veritatis Splendor Abstract A growing ecumenical awareness among Christian theologians and ethicists has found in John Paul II’s moral encyclical Veritatis Splendor a fresh impetus for a development of common studies of moral issues. Not few mainly Protestant ethicists expressed their com- ments on the way the Pope discusses and defines fundamental problems of Christian moral teaching. Some of those comments were apparently positive, at times even enthusiastic (e.g. R. Benne, S. Hauerwas, O. O’Donovan, J.B. Elshtain), while others displayed a mixed reaction to the papal teaching (e.g. L.S. Mudge. G. Meilaender, M. Banner). There were also some authors who approached Veritatis Splendor critically, some even rejected it alto- gether (e.g. N.P. Harvey, R. Preston, H. Oppenheimer). Keywords: Veritatis splendor, moral theology/Christian ethics, ecumenical dialogue, Christian moral life. Niekatolickie reakcje na Veritatis Splendor Streszczenie Wraz z coraz głębszym zrozumieniem prawdy o tym, że „kto podziela jedną wiarę w Chrystusa, winien dzielić także jedno życie w Chrystusie” (ARCIC II, Life in Christ), tematyka moralna znajduje dla siebie coraz więcej miejsca w dialogu ekumenicznym. Zarazem chrześcijanie różnych tradycji mają coraz większą świadomość konieczności dawania wspólnego świadectwa wobec świata, także co do życia moralnego uczniów Chrystusa. Szczególnym źródłem dla ekumenicznych debat nad fundamentalnymi prob- lemami chrześcijańskiego nauczania moralnego stała się encyklika Jana Pawła II Veri- tatis splendor. Liczne grono etyków i teologów, głównie protestanckich (luterańskich, anglikańskich, metodystycznych i innych), dało wyraz swoim przekonaniom, odnosząc się do podstawowych bądź bardziej szczegółowych zagadnień, przedstawionych w tym doku- mencie. -

Presidential Address ECUMENICAL DIALOGUE: the NEXT GENERATION

● CTSA PROCEEDINGS 63 (2008): 84-103 ● Presidential Address ECUMENICAL DIALOGUE: THE NEXT GENERATION INTRODUCTION In my title, Star Trek fans among us will recognize the name of the second series that followed the first famous group of space travellers in Star Trek who set out to explore new worlds. The next generation faced both old and new challenges: “to explore new worlds . , to boldly go where no one has gone before.” In some ways, ecumenical dialogue does boldly explore new worlds, and it presents Catholic theologians today with a number of important challenges. This convention on the theme “Generations” has given us many exciting opportunities to explore theological shifts from one generation to another. For our closing reflection, I have decided to talk about what a new generation of ecumenists will face as they explore this new world. To begin, I want to note my personal obligations to the generation in my own family that helped prepare the Roman Catholic Church for entrance into the ecumenical movement. Long before the Second Vatican Council passed its De- cree on Ecumenism, I had learned about ecumenism from my parents, James and Joan O’Gara, both fervent Chicago Catholics who met in a discussion group at the Chicago Catholic Worker and became committed to the renewal of the Catholic Church. During the 1930s and 1940s, my mother helped direct the huge Chicago Interstudent Catholic Action and my father ran the Chicago Catholic Worker House; for both, the dialogue with other Christians was part of what the renewal of Catholicism meant. When I was four years old, my father became managing editor of Commonweal magazine; when I was twelve years old, I decided to become a theologian.