Fides Et Ratio: Theology and Contemporary Pluralism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesia De Eucharistia on Its Ecumenical Import

Ecumenical & Interfaith Commission: www.melbourne.catholic.org.au/eic Ecclesia de Eucharistia On Its Ecumenical Import By Clint Le Bruyns (Clint Le Bruyns, is an Anglican ecumenist who is currently completing a research project on contemporary Anglican and Protestant perspectives on the Petrine ministry at the University of Stellenbosch in South Africa, where he also serves in the faculty of theology as Assistant Lecturer and Research Development Coordinator of the Beyers Naude Centre for Public Theology.) The pope’s latest encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church) – the fourteenth in his 25-year pontificate - was released in Rome on Maundy or Holy Thursday, April 17, 2003.1 Flanked by an introduction (1-10) and conclusion (59-62), the papal letter comprises six critical sections in which the Eucharist is discussed: The Mystery of Faith (11-20); The Eucharist Builds the Church (21-25); The Apostolicity of the Eucharist and of the Church (26-33); The Eucharist and Ecclesial Communion (34-46); The Dignity of the Eucharistic Celebration (47-52); and At the School of Mary, “Woman of the Eucharist” (53-58). Published in English, French, Italian, Spanish, German, Portuguese and Latin, it is a personal, warm, and passionate letter by the current pope on a longstanding theological treasure and dilemma (cf. 8). Like all papal encyclicals it is an internal theological document, bearing the full authority of the Vatican and addressing a matter of grave importance and concern for Roman Catholic faith, life and ministry. But papal texts are no longer merely Roman Catholic in orientation and scope. -

Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History

religions Article Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History Enrico Beltramini Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont, CA 94002, USA; [email protected] Abstract: How to deal with religious ideas in religious history (and in history in general) has recently become a matter of discussion. In particular, a number of authors have framed their work around the concept of ‘sacramental ontology,’ that is, a unified vision of reality in which the secular and the religious come together, although maintaining their distinction. The authors’ choices have been criticized by their fellow colleagues as a form of apologetics and a return to integralism. The aim of this article is to provide a proper context in which to locate the phenomenon of sacramental ontology. I suggest considering (1) the generation of the concept of sacramental ontology as part of the internal dialectic of the Christian intellectual world, not as a reaction to the secular; and (2) the adoption of the concept as a protection against ontological nihilism, not as an attack on scientific knowledge. Keywords: sacramental ontology; history; dualism; immanentism; nihilism Citation: Beltramini, Enrico. 2021. Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History. Religions 12: 47. https://doi.org/ 1. Introduction 10.3390rel12010047 A specter is haunting the historical enterprise, the specter of ‘sacramental ontology.’ Received: 3 December 2020 The specter of sacramental ontology is carried by a generation of Roman Catholic and Accepted: 23 December 2020 Evangelical historians as well as historical theologians who aim to restore the sacred dimen- 1 Published: 11 January 2021 sion of nature. -

The Holy See

The Holy See VESPERS LITURGY ON THE OCCASION OF THE 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE PROMULGATION OF THE CONCILIAR DECREE "UNITATIS REDINTEGRATIO" HOMILY OF JOHN PAUL II Saturday, 13 November 2004 "But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ. For he is our peace" (Eph 2: 13ff.).1. With these words from his Letter to the Ephesians the Apostle proclaims that Christ is our peace. We are reconciled in him; we are no longer strangers but fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone (cf. Eph 2: 19ff.).We have listened to Paul's words on the occasion of this celebration that sees us gathered in the venerable Basilica built over the Apostle Peter's tomb. I cordially greet those taking part in the ecumenical conference organized for the 40th anniversary of the promulgation of the Decree Unitatis Redintegratio of the Second Vatican Council. I extend my greeting to the Cardinals, Patriarchs and Bishops taking part, to the Fraternal Delegates of the other Churches and Ecclesial Communities, and to the Consultors, guests and collaborators of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I thank you for having carefully examined the meaning of this important Decree and the actual and future prospects of the ecumenical movement. This evening we are gathered here to praise God from whom come every good endowment and every perfect gift (cf. Jas 1: 17), and to thank him for the rich fruit the Decree has yielded with the help of the Holy Spirit during these past 40 years.2. -

Saint John Henry Newman, Development of Doctrine, and Sensus Fidelium: His Enduring Legacy in Roman Catholic Theological Discourse

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2021): 60–89 Saint John Henry Newman, Development of Doctrine, and Sensus Fidelium: His Enduring Legacy in Roman Catholic Theological Discourse Kenneth Parker The whole Church, laity and hierarchy together, bears responsi- bility for and mediates in history the revelation which is contained in the holy Scriptures and in the living apostolic Tradition … [A]ll believers [play a vital role] in the articulation and development of the faith …. “Sensus fidei in the life of the Church,” 3.1, 67 International Theological Commission of the Catholic Church Rome, July 2014 N 2014, THE INTERNATIONAL THEOLOGICAL Commission pub- lished “Sensus fidei in the life of the Church,” which highlighted two critically important theological concepts: development and I sensus fidelium. Drawing inspiration directly from the works of John Henry Newman, this document not only affirmed the insights found in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), which church authorities embraced during the first decade of New- man’s life as a Catholic, but also his provocative Rambler article, “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine” (1859), which resulted in episcopal accusations of heresy and Newman’s delation to Rome. The tension between Newman’s theory of development and his appeal for the hierarchy to consider the experience of the “faithful” ultimately centers on the “seat” of authority, and whose voices matter. As a his- torical theologian, I recognize in the 175 year reception of Newman’s theory of development, the controversial character of this historio- graphical assumption—or “metanarrative”—which privileges the hi- erarchy’s authority to teach, but paradoxically acknowledges the ca- pacity of the “faithful” to receive—and at times reject—propositions presented to them as authoritative truth claims.1 1 Maurice Blondel, in his History and Dogma (1904), emphasized that historians always act on metaphysical assumptions when applying facts to the historical St. -

Ut Unum Sint

ENCYCLICAL LETTER UT UNUM SINT OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II ON COMMITMENT TO ECUMENISM 25 May 1995 INTRODUCTION 1. Ut unum sint! The call for Christian unity made by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council with such impassioned commitment is finding an ever greater echo in the hearts of believers, especially as the Year 2000 approaches, a year which Christians will celebrate as a sacred Jubilee, the commemoration of the Incarnation of the Son of God, who became man in order to save humanity. The courageous witness of so many martyrs of our century, including members of Churches and Ecclesial Communities not in full communion with the Catholic Church, gives new vigor to the Council’s call and reminds us of our duty to listen to and put into practice its exhortation. These brothers and sisters of ours, united in the selfless offering of their lives for the Kingdom of God, are the most powerful proof that every factor of division can be transcended and overcome in the total gift of self for the sake of the Gospel. Christ calls all his disciples to unity. My earnest desire is to renew this call today, to propose it once more with determination, repeating what I said at the Roman Coliseum on Good Friday 1994, at the end of the meditation on the Via Crucis prepared by my Venerable Brother Bartholomew, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. There I stated that believers in Christ, united in following in the footsteps of the martyrs, cannot remain divided. If they wish truly and effectively to oppose the world’s tendency to reduce to powerlessness the Mystery of Redemption, they must profess together the same truth about the Cross.1 The Cross! An anti-Christian outlook seeks to minimize the Cross, to empty it of its meaning, and to deny that in it man has the source of his new life. -

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family

Spring 2020 Booklist Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family JPI 510/729 Theological Anthropology McCarthy • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Burns, J., Ed. Theological Anthropology. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981. • Balthasar, Hans Urs. The Christian State of Life. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983. • ______. Theo-Drama II, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990. ISBN 0898702879 • ______. Theo-Drama III. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 11992. ISBN 089870295X. • De Lubac, H. The Drama of Atheist Humanism. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995. ISBN: 089870443X • De Lubac, H. A Brief Catechesis on Nature and Grace. Ignatius Press, 1984. ISBN: 0898700353 • John Paul II. Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body. Pauline, 1997. • Schmitz, K. The Gift: Creation. Marquette University Press, Milwaukee, 1982. • Scola. The Nuptial Mystery. Trans. M. Borras. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 2005. • Spaemann, R. Essays in Anthropology – Variations on a Theme. Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2010. JPI 532/707 Biblical Theology of Marriage and Family (OT) Atkinson • Holy Scriptures [The most recent edition of Ignatius Press’ RSV is particularly good.] • Biblical and Theological Foundation of the Family, Joseph Atkinson (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2014). • Jean-Baptiste Edart (with Himbaza and Schenker). The Bible on the Question of Homosexuality. (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2012). JPI 550/850 Gender and the Sexual Difference D.L. Schindler • Compendium of readings (available through Cognella) • Simon Baron-Cohen, The Essential Difference. (New York: Basic Books, 2003). • John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: Theology of the Body. • Eve Tushnet, Gay and Catholic (Ave Maria Press, 2014). -

H-France Review Vol. 12 (March 2012), No. 41 Kathleen A. Mulhern

H-France Review Volume 12 (2012) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 12 (March 2012), No. 41 Kathleen A. Mulhern, Beyond the Contingent. Epistemological Authority, a Pascalian Revival, and the Religious Imagination in Third Republic France. With a Foreword by Martha Hanna. Eugene, Or.: Pickwick Publications, 2011. xvii + 212 pp. Bibliography and index. $25.00 U.S. (pb). ISBN-13: 978-1-60899-370-3. Review by Stephen Schloesser, Loyola University Chicago. Kathleen Mulhern investigates a late-nineteenth-century deployment of the seventeenth-century thought of Blaise Pascal by French neo-Pascalians (“Pascalisants”). Pascal had never completely disappeared from the French literary scene. Seventy years after his death, he served Voltaire as a foil in the Remarques sur les Pensées de Pascal (1734); Condorcet’s edition of the Pensées (1776) was but one stage in his ever-shifting relationship with Pascal-Voltaire.[1] In the post-revolutionary Romantic period, Pascal re-appeared in 1835; a new critical edition proposed by Victor Cousin followed ten years later (1844). From the mid-century onward, Pascal’s nationalist function as the French literary genius enjoyed multiple new editions: Vinet (1848), Sainte-Beuve (1848), Havet (1852), Droz (1886), Michaut (1896), and Brunschvicg (1904) (p. 7). For the purposes of Mulhern’s story, there seems to be a missing link here between 1776 and 1835. That link is suggested by Darrin McMahon’s observation that (largely Catholic) opponents of the philosophes during the 1770s-1780s overlooked Pascal’s Jansenist associations (and Rousseau’s own philosophic position) in service of combating “rationalism.” Though clearly differing in world view, both Pascal and Rousseau “argued convincingly that the heart had reasons that reason knows not, that when left to themselves our rational faculties left us lifeless and cold, uncertain and unsure. -

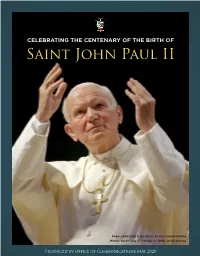

Saint John Paul II

CELEBRATING THE CENTENARY OF THE BIRTH OF Saint John Paul II Pope John Paul II gestures to the crowd during World Youth Day in Denver in 1993. (CNS photo) Produced by Office of Communications May 2020 On April 2, 2020 we commemorated the 15th Anniversary of St. John Paul II’s death and on May 18, 2020, we celebrate the Centenary of his birth. Many of us have special personal We remember his social justice memories of the impact of St. John encyclicals Laborem exercens (1981), Paul II’s ecclesial missionary mysticism Sollicitudo rei socialis (1987) and which was forged in the constant Centesimus annus (1991) that explored crises he faced throughout his life. the rich history and contemporary He planted the Cross of Jesus Christ relevance of Catholic social justice at the heart of every personal and teaching. world crisis he faced. During these We remember his emphasis on the days of COVID-19, we call on his relationship between objective truth powerful intercession. and history. He saw first hand in Nazism We vividly recall his visits to Poland, and Stalinism the bitter and tragic BISHOP visits during which millions of Poles JOHN O. BARRES consequences in history of warped joined in chants of “we want God,” is the fifth bishop of the culture of death philosophies. visits that set in motion the 1989 Catholic Diocese of Rockville In contrast, he asked us to be collapse of the Berlin Wall and a Centre. Follow him on witnesses to the Splendor of Truth, fundamental change in the world. Twitter, @BishopBarres a Truth that, if followed and lived We remember too, his canonization courageously, could lead the world of Saint Faustina, the spreading of global devotion to bright new horizons of charity, holiness and to the Divine Mercy and the establishment of mission. -

The Philosophy of William James As Related to Charles Renouvier, Henri Bergson, Maurice Blondel and Emile Boutroux

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1987 The philosophy of William James as related to Charles Renouvier, Henri Bergson, Maurice Blondel and Emile Boutroux Peggy Lyne Hurtado Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Intellectual History Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hurtado, Peggy Lyne, "The philosophy of William James as related to Charles Renouvier, Henri Bergson, Maurice Blondel and Emile Boutroux" (1987). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3713. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5597 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. ---- l I AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Peggy Lyne Hurtado for the Master of Arts in History presented June 10, 1987. Title: The Philosophy of William James as Related to Charles Renouvier, Henri Bergson, Maurice Blondel and Emile Boutroux. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Michael F. Reard~n, Chairman Guin~ David Joh This thesis argues two issues: William James' philosophy was-to a great extent derived from his interaction with the French philosophers, Charles Renouvier, Henri Bergson, Maurice Blondel and Emile Boutroux. Correlative to the fact that these five figures have an intellectual 2 relationship with one another, I also argue that in order to understand James, he must be placed within the context of these relations. -

Download Download

Implementing the Principles of the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church in Catholic Higher Education1 His Eminence Renato Raffaele Cardinal Martino The purpose of this discussion is to share a refl ection on the imple- mentation of Catholic Social Teaching (CST) in the ministry of Catholic higher education. In particular, I wish to highlight the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church2 that was completed by the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace at the request of the Servant of God, Pope John Paul II. Designed to be a user-friendly synthesis of the principles of CST, the Compendium has proven to be an extremely practical and substantial resource. It has now been translated into 40 different lan- guages and is widely available throughout the world. In a certain sense, the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church has been called “the Church’s best kept secret.” Why is this the case? Before the publication of the Compendium, perhaps because the social teach- ings of the popes were responding to specifi c situations (such as the cir- cumstances of the workers at the end of nineteenth century examined by Pope Leo XIII in his Encyclical Rerum novarum3), a well-structured exposition of the social doctrine of the Church did not exist. It was not until 1999 that Pope John Paul II, in his exhortation Ecclesia in America4, promised a document that would synthesize the social doc- trine of the Church. He then asked the Pontifi cal Council for Justice and Peace to prepare such a document—the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church—which was fi rst released on October 25, 2004. -

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas Thomas Aquinas: Teacher of Humanity Edited by John P. Hittinger and Daniel C. Wagner Proceedings from the First Conference of the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas held in the United States of America Thomas Aquinas: Teacher of Humanity Edited by John P. Hittinger and Daniel C. Wagner This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by John P. Hittinger, Daniel C. Wagner and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7554-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7554-7 DEDICATION TO THE MEMORY OF REV. VICTOR BREZIK, C.S.B. 1913-2009 TEXAN—BASILIAN—THOMIST Father Victor Brezik, who joined the University of St. Thomas faculty in 1954, adopted as his personal motto, “Dare to do whatever you can,” from his favorite philosopher, St. Thomas Aquinas. Fr. Brezik’s philosophical attitude and vision inspired generations of students and colleagues. In addition to his many contributions to the University, Fr. Brezik co-founded with Hugh Roy Marshall the University of St. Thomas’ Center for Thomistic Studies in 1975. The Center for Thomistic Studies, where the wisdom of Thomas Aquinas could be brought to bear on the problems of the contemporary world, was Fr. -

Supplementary Anselm-Bibliography 11

SUPPLEMENTARY ANSELM-BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is supplementary to the bibliographies contained in the following previous works of mine: J. Hopkins, A Companion to the Study of St. Anselm. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972. _________. Anselm of Canterbury: Volume Four: Hermeneutical and Textual Problems in the Complete Treatises of St. Anselm. New York: Mellen Press, 1976. _________. A New, Interpretive Translation of St. Anselm’s Monologion and Proslogion. Minneapolis: Banning Press, 1986. Abulafia, Anna S. “St Anselm and Those Outside the Church,” pp. 11-37 in David Loades and Katherine Walsh, editors, Faith and Identity: Christian Political Experience. Oxford: Blackwell, 1990. Adams, Marilyn M. “Saint Anselm’s Theory of Truth,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, I, 2 (1990), 353-372. _________. “Fides Quaerens Intellectum: St. Anselm’s Method in Philosophical Theology,” Faith and Philosophy, 9 (October, 1992), 409-435. _________. “Praying the Proslogion: Anselm’s Theological Method,” pp. 13-39 in Thomas D. Senor, editor, The Rationality of Belief and the Plurality of Faith. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. _________. “Satisfying Mercy: St. Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo Reconsidered,” The Modern Schoolman, 72 (January/March, 1995), 91-108. _________. “Elegant Necessity, Prayerful Disputation: Method in Cur Deus Homo,” pp. 367-396 in Paul Gilbert et al., editors, Cur Deus Homo. Rome: Prontificio Ateneo S. Anselmo, 1999. _________. “Romancing the Good: God and the Self according to St. Anselm of Canterbury,” pp. 91-109 in Gareth B. Matthews, editor, The Augustinian Tradition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999. _________. “Re-reading De Grammatico or Anselm’s Introduction to Aristotle’s Categories,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, XI (2000), 83-112.