Supplementary Anselm-Bibliography 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday Is the First Sunday After Pentecost in the Western Christian Liturgical Calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity

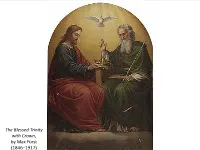

The Blessed Trinity with Crown, by Max Fürst (1846–1917) Welcome to OUR 15th VIRTUAL GSP class! Trinity Sunday and the Triune God WHAT IS IT? WHY IS IT? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. First Sunday after Pentecost: Trinity Sunday Almighty and everlasting God, who hast given unto us thy servants grace, by the confession of a true faith, to acknowledge the glory of the eternal Trinity, and in the power of the Divine Majesty to worship the Unity: We beseech thee that thou wouldest keep us steadfast in this faith and worship, and bring us at last to see thee in thy one and eternal glory, O Father; who with the Son and the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF THIS COLLECT? This collect, found in the first Book of Common Prayer, derives from a little sacramentary of votive Masses for the private devotion of priests prepared by Alcuin of York (c.735-804), a major contributor to the Carolingian Renaissance. It is similar to proper prefaces found in the 8th-century Gelasian and 10th- century Gregorian Sacramentaries. Gelasian Sacramentary WHAT IS TRINITY SUNDAY? Trinity Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost in the Western Christian liturgical calendar, and Pentecost Sunday in Eastern Christianity. It is eight weeks after Easter Sunday. The earliest possible date is 17 May and the latest possible date is 20 June. In 2021 it occurs on 30 May. One of the seven principal church year feasts (BCP, p. 15), Trinity Sunday celebrates the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the three Persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, “the one and equal glory” of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, “in Trinity of Persons and in Unity of Being” (BCP, p. -

Erasmus on the Study of Scriptures

-- CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY Erasmus the Exegete MARVIN ANDERSON Erasmm on the Study of Scriptures CARL S. MEYER Erasmus, Luther, and Aquinas PHILIP WATSON Forms of Church and Ministry ERWIN L. LUEKER Homiletics Book Review Vol. XL December 1969 No. 11 Erasmus on the Study of Scriptures CARL S. MEYER Erasmus (1469-1536)1 was the editor one of the important theologians of the of the first published Greek New Tes first half of the 16th century 6 as well as tament printed from movable type (1516).2 an earnest advocate of the study of Scrip He translated the books of the New Testa tures.7 ment into Latin 3 and also paraphrased I them (except Revelation) in that lan Prerequisites for Biblical studies coin guage.4 He published the notes of Lorenzo cide with the characteristics one brings to Valla (1406--1457) on the New Testa the philosophy of Christ, Erasmus held. ment.5 He must likewise be accounted as This meant a heart undefiled by the sordid ness of vice and unaffected by the dis 1 The standard edition of Erasmus' writings is DesMerii Erasmi Roterodami Opera Omnia, quietude of greed.8 We must therefore ed. J. Clericus (10 vols.; Leyden, 1703-1706). examine the philosophia Christi concept The reprint issued by Gregg Press in London, in Erasmus as the basis for understanding 1961-1962, was used. Cited as LB. Ausgewiihtte Werke, ed. Hajo Holborn his approach to Sacred Writ. (Munich: C. H. Vedagsbuchhandlung, 1933). Erasmus used a variety of phrases for Cited as AW. Ausgewiihlte Schriften, ed. Werner Welzig this concept. -

RELG 399 Fall2019

McGill University School of Religious Studies RELG 399 TEXTS OF CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY (Late Antiquity) In the Fall Term of 2019 this seminar course will focus on Christian spirituality in Late Antiquity with close study and interpretation of Aurelius Augustine’s spiritual odyssey the Confessiones, his account of creation in De genesi ad litteram, and his handbook of hermeneutics De doctrina Christiana. We will also read Ancius Manlius Severinus Boethius’s treatment of theodicy in De consolatione philosophiae, his De Trinitate, and selections from De Musica. Professor: Torrance Kirby Office Hours: Birks 206, Tuesdays/Thursdays, 10:00–11:00 am Email: [email protected] Birks Building, Room 004A Tuesdays/Thursdays 4:05–5:25 pm COURSE SYLLABUS—FALL TERM 2019 Date Reading 3 September INTRODUCTION 5 September Aurelius Augustine, Confessiones Book I, Early Years 10 September Book II, Theft of Pears 12 September Book III, Adolescence and Student Life 17 September Book IV, Manichee and Astrologer 19 September Book V, Carthage, Rome, and Milan *Confirm Mid-Term Essay Topics (1500-2000 words) (NB Consult the Style Sheet, essay-writing guidelines and evaluation rubric in the appendix to the syllabus.) 24 September Book VI, Secular Ambitions and Conflicts 26 September Book VII, Neoplatonic Quest for the Good 1 October Book VIII, Tolle, lege; tolle, lege 3 October Book IX, Vision at Ostia 8 October Book X, 1-26 Memory *Mid-term Essays due at beginning of class. Essay Conferences to be scheduled for week of 21 October 10 October Book X, 27-43 “Late have I loved you” 15 October Book XI, Time and Eternity 17 October Book XII, Creation Essay Conferences begin this week, Birks 206. -

Lent/Easter Newsletter

New Camaldoli Hermitage LENT/EASTER 2021 New Wineskins And no one puts new wine into old wineskins. If he does, the new wine will burst the skins and it will be spilled, and the skins will be destroyed. – Luke 5:37 62475 Highway 1, Big Sur, CA 93920 • 831 667 2456 • www.contemplation.com LENT/EASTER 2021 Community as an Ecosystem and Energy In This Issue Prior Cyprian Consiglio, OSB Cam. 2 Community as an Ecosystem and Energy I attended the Workshop for Prioresses and Abbots (and Prior Cyprian Consiglio, OSB Cam. Priors!) some years back, shortly after I had assumed the mantle of leadership here at New Camaldoli. The work- 4 Contemplative Renewal and New Monasticism shop was entitled “Leadership in a Complicated Rapidly Fr. Adam Bucko Changing World.” It was filled with the best advice I have 6 Camaldolese Charism Wine for New Wineskins gotten about being the prior of this community, and Andrea Seitz, Oblate, OSB Cam. phrases from it continu- ally come to my mind 7 Bede, Bruno, and New Consciousness when I am thinking Dorothea Derickson about “the big picture” here at the Hermitage 9 New Wineskins Retreat and of the future of reli- Helena Chan, Oblate, OSB Cam. gious life in general. 10 Renewal of Heart and Soul Fr. Steve Coffey, OSB Cam. The presenters first offered us two images: 11 What the Monks Are Reading one could see a com- munity either as a 11 Activities and Visitors fortress or as an eco- system. A fortress is an institution, built on a high. -

Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History

religions Article Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History Enrico Beltramini Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont, CA 94002, USA; [email protected] Abstract: How to deal with religious ideas in religious history (and in history in general) has recently become a matter of discussion. In particular, a number of authors have framed their work around the concept of ‘sacramental ontology,’ that is, a unified vision of reality in which the secular and the religious come together, although maintaining their distinction. The authors’ choices have been criticized by their fellow colleagues as a form of apologetics and a return to integralism. The aim of this article is to provide a proper context in which to locate the phenomenon of sacramental ontology. I suggest considering (1) the generation of the concept of sacramental ontology as part of the internal dialectic of the Christian intellectual world, not as a reaction to the secular; and (2) the adoption of the concept as a protection against ontological nihilism, not as an attack on scientific knowledge. Keywords: sacramental ontology; history; dualism; immanentism; nihilism Citation: Beltramini, Enrico. 2021. Between Dualism and Immanentism Sacramental Ontology and History. Religions 12: 47. https://doi.org/ 1. Introduction 10.3390rel12010047 A specter is haunting the historical enterprise, the specter of ‘sacramental ontology.’ Received: 3 December 2020 The specter of sacramental ontology is carried by a generation of Roman Catholic and Accepted: 23 December 2020 Evangelical historians as well as historical theologians who aim to restore the sacred dimen- 1 Published: 11 January 2021 sion of nature. -

Online Library of Liberty: the Dialogues of Plato, Vol. 1

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, vol. 1 [387 AD] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

![162 [Part I. Review of Erasmus's Preface]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3126/162-part-i-review-of-erasmuss-preface-133126.webp)

162 [Part I. Review of Erasmus's Preface]

162 WORD AND FAITH For although you think and write wrongly about free choice,k yet I owe you no small thanks, for you have made me far more sure of my own position by letting me see the case for free choice put forward with all the energy of so distinguished and powerful a mind, but with no other effect than to make things worse than 27. Luther had stated this as early as before. That is plain evidence that free choice is a pure fiction;27 in his 1518 Heidelberg Disputation (WA for, like the woman in the Gospel [Mark 5:25f.], the more it is 1:353–74; LW 31:[37–38] 39–70). Here treated by the doctors, the worse it gets. I shall therefore abun- he explains the free will to be just a dantly pay my debt of thanks to you, if through me you become word, not a real thing (res de solo titulo). better informed, as I through you have been more strongly con- firmed. But both of these things are gifts of the Spirit, not our own achievement. Therefore, we must pray that God may open my mouth and your heart, and the hearts of all human beings, and that God may be present in our midst as the master who informs both our speaking and hearing. But from you, my dear Erasmus, let me obtain this request, that just as I bear with your ignorance in these matters, so you in turn will bear with my lack of eloquence. God does not give all his gifts to one man, and “we cannot all do all things”; or, as Paul says: “There are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit” [1 Cor. -

Anselm's Cur Deus Homo

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo: A Meditation from the Point of View of the Sinner Gene Fendt Elements in Anselm's Cur Deus Homo point quite differently from the usual view of it as the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam. This meditation will attempt to bring out how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon faith and conscience drives the sinner to see the necessity of the marriage of human with divine natures offered in Christ and how that marriage raises both man and creation out of sin and its defects. This explanation should exhibit both to believers, who seek to understand, and to unbelievers (primarily Jews and Muslims), from a common root, a solution "intelligible to all, and appealing because of its utility and the beauty of its reasoning" (1.1). Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo is the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam (and company).1 There are elements in it, however, which seem to point quite differently from such a view. This meditation will attempt to bring further into the open how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon “faith and conscience”2 shows something new in this Paschal event, which cannot be well accommodated to the view which makes Christ a scapegoat killed for our sin.3 This ergon upon the conscience I take—in what I trust is a most suitably monastic fashion—to be more important than the theoretical theological shell which Anselm’s discussion with Boso more famously leaves behind. -

Life and Works of Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux

J&t. itfetnatto. LIFE AND WORKS OF SAINT BERNARD, ABBOT OF CLA1RVAUX. EDITED BY DOM. JOHN MABILLON, Presbyter and Monk of the Benedictine Congregation of S. Maur. Translated and Edited with Additional Notes, BY SAMUEL J. EALES, M.A., D.C.L., Sometime Principal of S. Boniface College, Warminster. SECOND EDITION. VOL. I. LONDON: BURNS & OATES LIMITED. NEW YORK, CINCINNATI & CHICAGO: BENZIGER BROTHERS. EMMANUBi A $ t fo je s : SOUTH COUNTIES PRESS LIMITED. .NOV 20 1350 CONTENTS. I. PREFACE TO ENGLISH EDITION II. GENERAL PREFACE... ... i III. BERNARDINE CHRONOLOGY ... 76 IV. LIST WITH DATES OF S. BERNARD S LETTERS... gi V. LETTERS No. I. TO No. CXLV ... ... 107 PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION. THERE are so many things to be said respecting the career and the writings of S. Bernard of Clairvaux, and so high are view of his the praises which must, on any just character, be considered his due, that an eloquence not less than his own would be needed to give adequate expression to them. and able labourer He was an untiring transcendently ; and that in many fields. In all his manifold activities are manifest an intellect vigorous and splendid, and a character which never magnetic attractiveness of personal failed to influence and win over others to his views. His entire disinterestedness, his remarkable industry, the soul- have been subduing eloquence which seems to equally effective in France and in Italy, over the sturdy burghers of and above of Liege and the turbulent population Milan, the all the wonderful piety and saintliness which formed these noblest and the most engaging of his gifts qualities, and the actions which came out of them, rendered him the ornament, as he was more than any other man, the have drawn him the leader, of his own time, and upon admiration of succeeding ages. -

Saint John Henry Newman, Development of Doctrine, and Sensus Fidelium: His Enduring Legacy in Roman Catholic Theological Discourse

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2021): 60–89 Saint John Henry Newman, Development of Doctrine, and Sensus Fidelium: His Enduring Legacy in Roman Catholic Theological Discourse Kenneth Parker The whole Church, laity and hierarchy together, bears responsi- bility for and mediates in history the revelation which is contained in the holy Scriptures and in the living apostolic Tradition … [A]ll believers [play a vital role] in the articulation and development of the faith …. “Sensus fidei in the life of the Church,” 3.1, 67 International Theological Commission of the Catholic Church Rome, July 2014 N 2014, THE INTERNATIONAL THEOLOGICAL Commission pub- lished “Sensus fidei in the life of the Church,” which highlighted two critically important theological concepts: development and I sensus fidelium. Drawing inspiration directly from the works of John Henry Newman, this document not only affirmed the insights found in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), which church authorities embraced during the first decade of New- man’s life as a Catholic, but also his provocative Rambler article, “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine” (1859), which resulted in episcopal accusations of heresy and Newman’s delation to Rome. The tension between Newman’s theory of development and his appeal for the hierarchy to consider the experience of the “faithful” ultimately centers on the “seat” of authority, and whose voices matter. As a his- torical theologian, I recognize in the 175 year reception of Newman’s theory of development, the controversial character of this historio- graphical assumption—or “metanarrative”—which privileges the hi- erarchy’s authority to teach, but paradoxically acknowledges the ca- pacity of the “faithful” to receive—and at times reject—propositions presented to them as authoritative truth claims.1 1 Maurice Blondel, in his History and Dogma (1904), emphasized that historians always act on metaphysical assumptions when applying facts to the historical St. -

Intellectual Elitism and the Need for Faith in Maimonides and Aquinas

INTELLECTUAL ELITISM AND THE NEED FOR FAITH Intellectual elitism and the need for faith in Maimonides and Aquinas Elitismo intelectual y la necesidad de la fe según Maimónides y Tomás de Aquino FRANCISCO ROMERO CARRASQUILLO Departamento de Humanidades Universidad Panamericana 45010 Zapopan, Jalisco (México) [email protected] Abstract: In his Commentary on Boethius’ De Resumen: En su Comentario al De Trinitate de Trinitate 3.1, Aquinas cites Maimonides as Boecio 3.1, Tomás de Aquino cita a Maimóni- giving fi ve reasons for the need for faith. Yet des, de quien afi rma que presenta cinco ra- interpreters tend to see Aquinas as “stand- zones a favor de la necesidad de la fe. Los in- ing Maimonides on his head”. In this paper, térpretes suelen ver a Tomás de Aquino como the author places Maimonides’ text (on the si “hubiera puesto a Maimónides de cabeza”. five reasons for concealing metaphysics) En el presente artículo se retoma el texto de within the context of his rational mysticism Maimónides (acerca de las cinco razones por and compares it to Aquinas’ own Christian las que la metafísica debe reservarse a los mystical thought in an attempt to show that doctos y ocultarse a las masas), y se sitúa en el in his own mind Aquinas is not misquoting, contexto de su misticismo racional. Compa- reversing, or doing violence to Maimonides’ rándolo con el pensamiento místico cristiano text; rather, Aquinas is completing Maimon- de Tomás de Aquino, se muestra cómo éste ides’ natural, rational mysticism with what he no está citando erróneamente, ni invirtiendo understands to be the supernatural perfec- ni violentando el texto de Maimónides; más tion of the theological virtue of faith. -

Bonaventure's Threefold Way to God

BONAVENTURE’S THREE-FOLD WAY TO GOD R. E. Houser Though he became Minister General of the Franciscan Order in 1257, Bonaventure’s heart never left the University of Paris, and during his generalate he delivered three sets of “collations” or university sermons at Paris. On 10 December 1270 Itienne Tempier, bishop of Paris, had condemned certain erroneous propositions. Bonaventure ruminated over these matters, and in the Spring of 1273 delivered his magisterial Collations on the Hexameron.1 Left 1 For Bonaventure’s dates see J.G. Bougerol, Introduction a l’étude de saint Bonaventure 2nd ed. (Paris: Vrin, 1988); J. Quinn, “Bonaventure” Dict. of the M.A. 2: 313-9. On the circumstances of the Collations, one friar noted: “But oh, no, no, no! Since the reverend Lord and Master who gave out this work has been elevated to a sublime position, and is leaving his way of life [as a friar], those attending his sermons have not received what was to follow [the missing last three collations]. This work was read and composed at Paris, in the year of our Lord 1273, from Easter to Pentecost, there being present Masters and Bachelors of Theology and other brothers, in the number of 160.” Bonaventure, Opera Omnia (ed. Quaracchi) 5: 450 n. 10; Coll. in Hex. ed. F. Delorme (Quaracchi: 1934) 275. 92 unfinished owing to his elevation to the cardinalate, in them he read the first chapter of Genesis spiritually, distinguishing seven levels of “vision” corresponding to the seven days of creation. The first level is “understanding naturally given” or philosophy, divided into logic, physics, and ethics.