Early Medieval G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, Special Issue 2 (2017): 112-137 Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract ‘On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’ Julia A. Fleming N 1639, THE FAMOUS THEATINE casuist Antonino Diana published the fifth part of his Resolutiones morales, a volume that included a tract regarding the mute, deaf, and blind.1 Structured I as a series of cases (i.e., questions and answers), its form resembles tracts in Diana’s other volumes concerning members of particular groups, such as vowed religious, slaves, and executors of wills.2 While the arrangement of cases within the tract is not systematic, they tend to fall into two broad categories, the first regarding the status of persons with specified disabilities in the Church and the second in civil society. Diana draws the cases from a wide variety of sources, from Thomas Aquinas and Gratian to later experts in theology, pastoral practice, canon law, and civil law. The tract is thus a reference collection rather than a monograph, although Diana occasionally proposes a new question for his colleagues’ consideration. “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind” addresses thirty-seven different cases, some focused upon persons with a single disability, and others, on persons with combination of these three disabilities. Specific cases hinge upon further distinctions. Is the individual in question completely or partially blind, totally deaf or hard of hearing, mute or beset with a speech impediment? Was the condition present from birth 1 Antonino Diana, Resolutionum moralium pars quinta (hereafter RM 5) (Lyon, France: Sumpt. -

Anselm's Cur Deus Homo

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo: A Meditation from the Point of View of the Sinner Gene Fendt Elements in Anselm's Cur Deus Homo point quite differently from the usual view of it as the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam. This meditation will attempt to bring out how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon faith and conscience drives the sinner to see the necessity of the marriage of human with divine natures offered in Christ and how that marriage raises both man and creation out of sin and its defects. This explanation should exhibit both to believers, who seek to understand, and to unbelievers (primarily Jews and Muslims), from a common root, a solution "intelligible to all, and appealing because of its utility and the beauty of its reasoning" (1.1). Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo is the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam (and company).1 There are elements in it, however, which seem to point quite differently from such a view. This meditation will attempt to bring further into the open how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon “faith and conscience”2 shows something new in this Paschal event, which cannot be well accommodated to the view which makes Christ a scapegoat killed for our sin.3 This ergon upon the conscience I take—in what I trust is a most suitably monastic fashion—to be more important than the theoretical theological shell which Anselm’s discussion with Boso more famously leaves behind. -

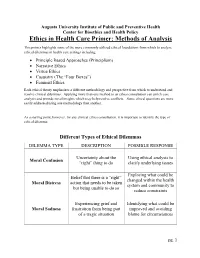

Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis

Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the more commonly utilized ethical foundations from which to analyze ethical dilemmas in health care settings including: • Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) • Narrative Ethics • Virtue Ethics • Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”) • Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and resolve clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insights which may help resolve conflicts. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one methodology than another. As a starting point, however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Uncertainty about the Using ethical analysis to Moral Confusion “right” thing to do clarify underlying issues Exploring what could be Belief that there is a “right” changed within the health Moral Distress action that needs to be taken system and community to but being unable to do so reduce constraints Experiencing grief and Identifying what could be Moral Sadness frustration from being part improved and avoiding of a tragic situation blame for circumstances pg. 1 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describes a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles central in the ethical practice of health care1: 1. -

A Theological Assessment of Anselm's Cur Deus Homo

123/2 master:119/3 19/5/09 12:40 Page 121 121 A Theological Assessment of Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo Dan Saunders The hypothesis of this article is that Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo shoUld not be regarded as a serioUs or complete theory of the atonement. This is dUe to its thoroUgh disregard of and incompatibility with ScriptUre, internal inconsistencies, errors and general theological inaccUracies. To prove this hypothesis we provide a biblical sUrvey of atonement themes and meaning. We examine the Mosaic sin-offering and atonement sacrifices of LeviticUs 4 and 16 and the Servant Song of Isaiah 53. We show that JesUs’ Understanding was that he was the Servant, as indicated by lingUistic and conceptUal connections in Mark 10:45b, LUke 22:37 and Acts 8. We conclUde that atonement mUst be viewed in relation to the salvific death of JesUs and explained with reference to the terms, metaphors and ideas Used in ScriptUre. We then sUrvey historical theology in order to place Cur Deus Homo in its appropriate historical context. OUr theological assessment then proceeds from both a scriptUral and historical perspective, while also noting the systematic and practical advances, implications and conseqUences of Cur Deus Homo . We conclUde that althoUgh a solid apologetic for the incarnation and a lasting repUdiation of the devil- ransom theory, Cur Deus Homo is deficient as a theory of the atonement. The satisfaction theory becomes little more than a moral theory and leads to other errors. The theory of penal sUbstitUtion by way of sacrificial ransom, best articUlated by the Reformers, is to be preferred as the view that most accords with ScriptUre. -

Cur Deus Homo (Why God Became Man) Free

FREE CUR DEUS HOMO (WHY GOD BECAME MAN) PDF St Anselm of Canterbury,James Gardiner Vose | 98 pages | 20 Nov 2015 | Createspace | 9781519419538 | English | United States Anselm on the Incarnation | Christian History Institute Anselm of Canterbury was a native of Aosta and the son of the Lombard landowner. He left home for France in and entered the monastic school at Bec in Normany inwhich was directed by the famous teacher Lanfranc of Pavia. He Cur Deus Homo (Why God Became Man) monastic vows insucceeded Lanfranc as prior inand became abbot in He would go on to follow Lanfranc as the Archbishop of Canterbury inand publish a number of important theological and philosophical works over the course of his career, including Monologion, Proslogion, and De Processione Sancti Spiritusas well as his theological masterpiece Cur Deus Homo (Why God Became Man) the atonement, Cur Deus Homo. Cur Deus Homo was written between and in response to two different challenges to the Christian faith: the Jewish criticisms of Christian doctrine and the theological debates of the secular schools. Jewish opponents questioned the necessity, possibility, and dignity of the incarnation and atonement. The schoolmen argued that God became man simply to deliver man from the dominion of the Devil. Against the latter he argues that God became man not to merely trick Satan into overstepping his authority but to make satisfaction for sin. The work takes the form of a discussion between Anselm and his favorite pupil, Boso, who gives voice to the questions of unbelievers and believers. Their conversations are divided into two books and each book is subdivided into multiple chapters. -

NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, and the FUNCTION of CONSCIENCE in THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan –

Diametros 47 (2016): 1–18 doi: 10.13153/diam.47.2016.865 NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, AND THE FUNCTION OF CONSCIENCE IN THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan – Abstract. Both the function of one’s conscience, as Thomas Aquinas understands it, and the work of casuistry in general involve deliberating about which universal moral principles are applicable in particular cases. Thus, understanding how conscience can function better also indicates how casuistry might be done better – both on Thomistic terms, at least. I claim that, given Aquinas’ de- scriptions of certain parts of prudence (synesis and gnome) and the role of moral virtue in practical knowledge, understanding particular cases more as narratives, or parts of narratives, likely will result, all else being equal, in more accurate moral judgments of particular cases. This is especially important in two kinds of cases: first, cases in which Aquinas recognizes universal moral principles do not specify the means by which they are to be followed; second, cases in which the type-identity of an action – and thus the norms applicable to it – can be mistaken Keywords: Thomas Aquinas, conscience, narrative, casuistry, prudence, virtue, moral judgment, moral development, moral knowledge. Introduction ‘Casuistry’ has a bad reputation in some circles. It tends to be associated wi- th formalized, but too legalistic, approaches to determining and enumerating mo- ral faults. In a more generic sense, though, casuistry just refers to deliberating about and discerning what universal moral principles apply in particular cases, based on relevant details of the case at issue. As Thomas Aquinas understands things, casuistry parallels the ordinary, everyday function of one’s conscience, which specifically regards particular cases in which one deliberates about one’s own morally relevant actions.1 Given this, we might be able to gain insight to how formalized casuistry can be done well by drawing an analogy from what it takes for conscience to function well. -

Revisiting the Franciscan Doctrine of Christ

Theological Studies 64 (2003) REVISITING THE FRANCISCAN DOCTRINE OF CHRIST ILIA DELIO, O.S.F. [Franciscan theologians posit an integral relation between Incarna- tion and Creation whereby the Incarnation is grounded in the Trin- ity of love. The primacy of Christ as the fundamental reason for the Incarnation underscores a theocentric understanding of Incarnation that widens the meaning of salvation and places it in a cosmic con- tent. The author explores the primacy of Christ both in its historical context and with a contemporary view toward ecology, world reli- gions, and extraterrestrial life, emphasizing the fullness of the mys- tery of Christ.] ARL RAHNER, in his remarkable essay “Christology within an Evolu- K tionary View of the World,” noted that the Scotistic doctrine of Christ has never been objected to by the Church’s magisterium,1 although one might add, it has never been embraced by the Church either. Accord- ing to this doctrine, the basic motive for the Incarnation was, in Rahner’s words, “not the blotting-out of sin but was already the goal of divine freedom even apart from any divine fore-knowledge of freely incurred guilt.”2 Although the doctrine came to full fruition in the writings of the late 13th-century philosopher/theologian John Duns Scotus, the origins of the doctrine in the West can be traced back at least to the 12th century and to the writings of Rupert of Deutz. THE PRIMACY OF CHRIST TRADITION The reason for the Incarnation occupied the minds of medieval thinkers, especially with the rise of Anselm of Canterbury and his satisfaction theory. -

Supplementary Anselm-Bibliography 11

SUPPLEMENTARY ANSELM-BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is supplementary to the bibliographies contained in the following previous works of mine: J. Hopkins, A Companion to the Study of St. Anselm. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1972. _________. Anselm of Canterbury: Volume Four: Hermeneutical and Textual Problems in the Complete Treatises of St. Anselm. New York: Mellen Press, 1976. _________. A New, Interpretive Translation of St. Anselm’s Monologion and Proslogion. Minneapolis: Banning Press, 1986. Abulafia, Anna S. “St Anselm and Those Outside the Church,” pp. 11-37 in David Loades and Katherine Walsh, editors, Faith and Identity: Christian Political Experience. Oxford: Blackwell, 1990. Adams, Marilyn M. “Saint Anselm’s Theory of Truth,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, I, 2 (1990), 353-372. _________. “Fides Quaerens Intellectum: St. Anselm’s Method in Philosophical Theology,” Faith and Philosophy, 9 (October, 1992), 409-435. _________. “Praying the Proslogion: Anselm’s Theological Method,” pp. 13-39 in Thomas D. Senor, editor, The Rationality of Belief and the Plurality of Faith. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. _________. “Satisfying Mercy: St. Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo Reconsidered,” The Modern Schoolman, 72 (January/March, 1995), 91-108. _________. “Elegant Necessity, Prayerful Disputation: Method in Cur Deus Homo,” pp. 367-396 in Paul Gilbert et al., editors, Cur Deus Homo. Rome: Prontificio Ateneo S. Anselmo, 1999. _________. “Romancing the Good: God and the Self according to St. Anselm of Canterbury,” pp. 91-109 in Gareth B. Matthews, editor, The Augustinian Tradition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999. _________. “Re-reading De Grammatico or Anselm’s Introduction to Aristotle’s Categories,” Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, XI (2000), 83-112. -

Health Care Ethics and Casuistry

Jrournal ofmedical ethics, 1992, 18, 61-62, 66 J Med Ethics: first published as 10.1136/jme.18.2.61 on 1 June 1992. Downloaded from Guest editorial: A personal view Health care ethics and casuistry Robin Downie University ofGlasgow In an editorial (1) Dr Gillon looks at some recent method of teaching and discussing medical ethics. The difficulties which have been raised about philosophy answer to Smith here is to point out that what is taking and the teaching ofhealth care ethics. This matter is of place in such discussions is a form of what he calls sufficient importance to the readers of this journal that 'natural jurisprudence'. It is an attempt to translate it is worth looking at it again, this time in an historical into case law, to give concrete application to, the ideals perspective. contained in codes. If natural jurisprudence is a One claim which is often made by those advocating legitimate activity, so too is this. the study of health care ethics is that such a study will Smith's second group ofarguments against casuistry assist in the solving of what have come to be called are to the effect that it does not 'animate us to what is 'ethical dilemmas'. Since health care ethics is so widely generous and noble' but rather teaches us 'to chicane taught for this reason the claim is worth examining. Is with our consciences' (4). Smith is certainly correct in health care ethics in this sense possible? Is it desirable? claiming that casuistry is concerned mainly with whatcopyright. Is it philosophy? In other words, can a case be made out is required or forbidden, that is, with rules, rather than for what earlier centuries called 'casuistry, or the with questions of motivation. -

Christian History II: 500-1000

Europe was slowly being converted to Christianity. Missionaries came from Ireland and Italy [those were not countries at all in those days]. Eastern Europe and Scandinavia remained polytheistic until the 11th century. St. Willibrord and the Frisians Example: The challenge of communicating the Gospel. St. Willibrord worked among the Frisian tribes [today would today be the Netherlands] in 8th century. He convinced the king of the Frisians to become a Christian and to be baptized. Baptism [the Bath] carried heavy weight as the mark of being Christian as it does in most non-Christian cultures. As he stepped into the fountain for baptism, he asked Willibrord if he would see his forefathers in heaven. Willibrord explained that, no - his relatives would be in hell and not in heaven because they did not know Christ. The king then stepped out of the water and refused saying that he would rather die a pagan and see his family in hell than to be separated from them forever. The Frisians were not Christianized for another hundred years until they were conquered in battle by Charlemagne’s forces. Theology update: Theories of the Atonement • Anselm [Cur Deus Homo in 1095] made a major contribution to the Western understanding of the doctrine of atonement with his theory that Christ’s death made satisfaction for human sin. The doctrine of atonement has come to mean accounts or theories of how Christ’s death on the cross brought about forgiveness of sins. • In the Old Testament “atonement” was a word used to describe cleansing from sin through the blood of sacrifices. -

The New Casuistry

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers April 1999 The ewN Casuistry Paul R. Tremblay Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Paul R. Tremblay. "The eN w Casuistry." Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 12, no.3 (1999): 489-542. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The New Casuistry PAUL R. TREMBLAY* Of one thing we may be sure. If inquiries are to have substantialbasis, if they are not to be wholly in the air the theorist must take his departurefrom the problems which men actually meet in their own conduct. He may define and refine these; he may divide and systematize; he may abstract the problemsfrom their concrete contexts in individual lives; he may classify them when he has thus detached them; but ifhe gets away from them, he is talking about something his own brain has invented, not about moral realities. John Dewey and James Tufts' [A] "new casuistry" has appearedin which the old "method of cases" has been revived.... 2 Hugo Adam Bedau I. PRACTICING PHILOSOPHY Let us suppose, just for the moment, that "plain people ' 3 care about ethics, that they would prefer, everything else being equal, to do the right thing, or to lead the good life. -

Anselm on the Atonement in Cur Deus Homo: Salvation As a Gratuitous Grace

LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations 5-20-2018 Anselm on the Atonement in Cur Deus Homo: Salvation as a Gratuitous Grace Thu Nguyen Loyola Marymount University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Nguyen, Thu, "Anselm on the Atonement in Cur Deus Homo: Salvation as a Gratuitous Grace" (2018). LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations. 518. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd/518 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANSELM ON THE ATONEMENT IN CUR DEUS HOMO: SALVATION AS A GRATUITOUS GRACE by Thu Nguyen A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Department of Theological Studies Loyola Marymount University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Theological Studies May 20, 2018 Anselm on the Atonement in Cur Deus Homo: Salvation as a Gratuitous Grace Table of Contents Narrative ............................................................................................................................. 3 A brief summary of the theory of Anselm .......................................................................... 4 Chapter 1- THE CONTEXT OF CUR DEUS HOMO .......................................................