The Political Theology of David Hume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Varieties of Religious Naturalism

Varieties of Religious Naturalism Wesley J. Wildman — Boston University — Spring 2010 — STH TT861/TT961 Course Description The aim of this course is learn about varieties of religious naturalism and how they have been, and can be, incorporated into philosophical and theological reflection. The seminar will read a variety of works in contemporary religious naturalism, from twentieth-century classics to current contributions, and from theoretical analyses of the meaning of naturalism to surveys attempting to map out the territory of plausible viewpoints. We will also track the close relationship between religious naturalism and both ecologically-rooted forms of spirituality and nature-centered forms of mysticism. The class is intended for advanced masters students and doctoral candidates interested in contemporary forms of philosophical and theological reflection on nature and God, and in forms of spirituality rooted in the natural world. Students registered at the 900-level have readings and a bibliographic task to complete over and above the obligations of students registered at the 800-level. Classes will meet once a week on Wednesdays from 8:00 to 11:00 in STH 319. Each class will be conducted in the seminar discussion format with lectures given by the instructor as needed or requested. The 800-level version of this course counts (1) as an MTS Core Concentration course for Science and Religion, for Theology, and for Area B; and (2) as an MDiv Theology 3 Core Elective. It may also count (3) as a requirement for a BTI Certificate program in science and religion. The main product of the course will be a research paper on some aspect of the course material, topic to be approved in advance by the instructor (50%; 3,000 words for 800-level students, 5,000 words for 900-level students). -

On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, Special Issue 2 (2017): 112-137 Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract ‘On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’ Julia A. Fleming N 1639, THE FAMOUS THEATINE casuist Antonino Diana published the fifth part of his Resolutiones morales, a volume that included a tract regarding the mute, deaf, and blind.1 Structured I as a series of cases (i.e., questions and answers), its form resembles tracts in Diana’s other volumes concerning members of particular groups, such as vowed religious, slaves, and executors of wills.2 While the arrangement of cases within the tract is not systematic, they tend to fall into two broad categories, the first regarding the status of persons with specified disabilities in the Church and the second in civil society. Diana draws the cases from a wide variety of sources, from Thomas Aquinas and Gratian to later experts in theology, pastoral practice, canon law, and civil law. The tract is thus a reference collection rather than a monograph, although Diana occasionally proposes a new question for his colleagues’ consideration. “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind” addresses thirty-seven different cases, some focused upon persons with a single disability, and others, on persons with combination of these three disabilities. Specific cases hinge upon further distinctions. Is the individual in question completely or partially blind, totally deaf or hard of hearing, mute or beset with a speech impediment? Was the condition present from birth 1 Antonino Diana, Resolutionum moralium pars quinta (hereafter RM 5) (Lyon, France: Sumpt. -

Delegates Named for Celebration of Plenary

MEDIA RELEASE March 23, 2020 DELEGATES NAMED FOR CELEBRATION OF PLENARY COUNCIL Plenary Council president Archbishop Timothy Costelloe SDB has written to 266 other Catholics across the country, calling them as delegates for the Fifth Plenary Council of Australia. “At a time in our Church’s history we’ve not seen before, with the suspension of Masses in many parts of the country and around the world, the announcement of our Plenary Council delegates is a source of great joy for the People of God in Australia,” Archbishop Costelloe said. Canon law outlines those who must be called as delegates to a plenary council, including bishops, vicars general, episcopal vicars, heads of seminaries and theological institutions, and leaders of religious congregations. That amounted to 180 delegates. Canon law also allows for delegates who may be called as representatives – the total of which can’t exceed half of the total of those who must be called. The number of delegates from each local church – a diocese, eparchy, ordinariate or prelature – ranged from one to four depending on the local Catholic population. In all, 78 people have so far been confirmed, with additional representation to be named from national organisations representing education, social services, health and aged care, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Catholic. “Bishops across the country worked locally with leaders in their diocese to design a process to consider names of people who were nominated or applied to be delegates for the Plenary Council assemblies,” Archbishop Costelloe said. “We were grateful for and impressed with the faith and the calibre of the people who were nominated. -

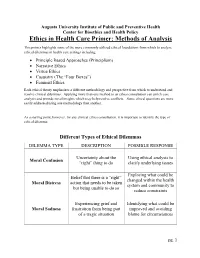

Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis

Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the more commonly utilized ethical foundations from which to analyze ethical dilemmas in health care settings including: • Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) • Narrative Ethics • Virtue Ethics • Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”) • Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and resolve clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insights which may help resolve conflicts. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one methodology than another. As a starting point, however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Uncertainty about the Using ethical analysis to Moral Confusion “right” thing to do clarify underlying issues Exploring what could be Belief that there is a “right” changed within the health Moral Distress action that needs to be taken system and community to but being unable to do so reduce constraints Experiencing grief and Identifying what could be Moral Sadness frustration from being part improved and avoiding of a tragic situation blame for circumstances pg. 1 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describes a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles central in the ethical practice of health care1: 1. -

1922 Addresses Gordon.Pdf

Addresses Biographical and Historical ALEXANDER GORDON, M.A. tc_' Sometime Lecturer in Ecclesiastical History in the University of fifanclzester VETUS PROPTER NO VUM DEPROMETIS THE LINDSEY PRESS 5 ESSEX STREET, STRAND, LONDON, W.C.2 1922 www.unitarian.org.uWdocs PREFATORY NOTE With three exceptions the following Addresses were delivered at the openings of Sessions of the Unitarian Home Missionary College, in Manchester, where the author was Principal from 1890 to 1911. The fifth Address (Salters' Hall) was delivered at the Opening Meeting of the High Pavement Historical Society, in Nottingham; the seventh (Doddridge) at Manchester College, in Oxford, in connection with the Summer Meeting of University Extension students ; The portrait prefixed is a facsimile, f~llsize, of the first issue of the original engraving by Christopher Sichem, from the eighth (Lindsey) at the Unitarian Institute, in the British Museum copy (698. a. 45(2)) of Grouwele.~,der Liverpool. vooruzaeutzster Hooft-Kettereuz, Leyden, 1607. In this volume the Addresses are arranged according to the chronology of their subjects; the actual date of delivery is added at the close of each. Except the first and the fifth, the Addresses were printed, shortly after delivery, in the Ch~istianLife newspaper ; these two (also the third) were printed separately; all have been revised, with a view as far as possible to reduce overlapping and to mitigate the use of the personal pronoun. Further, in the first Address it has been necessary to make an important correction in reference to the parentage of Servetus. Misled by the erroneous ascription to him of a letter from Louvain in 1538 signed Miguel Villaneuva (see the author's article Printed it1 Great Britain by on Servetus in the Encyclopwdia Britannica, also ELSOM& Co. -

STEPHEN TAYLOR the Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II

STEPHEN TAYLOR The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 129–151 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II STEPHEN TAYLOR In the years between the Reformation and the revolution of 1688 the court lay at the very heart of English religious life. Court bishops played an important role as royal councillors in matters concerning both church and commonwealth. 1 Royal chaplaincies were sought after, both as important steps on the road of prefer- ment and as positions from which to influence religious policy.2 Printed court sermons were a prominent literary genre, providing not least an important forum for debate about the nature and character of the English Reformation. -

Naturalistic Theism Teed Rockwell

Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism 25.2 (2017) 209–220 ISSN 1522-7340 (print) ISSN 2052-8388 (online) https://doi.org/10.1558/eph.34830 Naturalistic Theism Teed Rockwell Sonoma State University [email protected] Abstract Many modern theological debates are built around a false dichotomy between 1) an atheism which asserts that the universe was created by purposeless me- chanical processes and 2) acceptance of a religious system which requires both faith in the infallibility of sacred texts and belief in a supernatural God. I propose a form of naturalistic theism, which rejects sacred texts as unjustified, and supernaturalism as incoherent. I argue that rejecting these two elements of traditional organized religion would have a strongly positive impact on the beliefs and practices of religion, even though many religious people feel strongly attached to them. It is belief in sacred texts that is responsible for most of the evil done in the name of religion, not belief in God. Many of the strongest arguments for atheism work only against a supernatural God, and have no impact on the question of the existence of a natural God. Keywords atheism, theism, agnosticism, naturalism, supernaturalism, sacred text, Shook, Dennett, Dawkins, Kuhn, Quine, Neurath, Koran, Bible, Islam, Buddhism, omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent, miracles, Marxist atheism I agree with many of the criticisms of established religions voiced by promi- nent Atheists. That is why the only form of Theism I could accept would be what I call Naturalistic Theism. For many Atheists, this will appear to be a contradiction in terms, but I will argue that this kind of theism is as com- patible with science as nondogmatic Atheism.1 As far as I can tell, Natural- istic Theism is essentially identical to what John Shook calls either Religious 1. -

Summary of the Plenary Meeting of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference Held at Mary Mackillop Place, Mount Street, North Sydney, Nsw

SUMMARY OF THE PLENARY MEETING OF THE AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC BISHOPS CONFERENCE HELD AT MARY MACKILLOP PLACE, MOUNT STREET, NORTH SYDNEY, NSW. 3 – 10 May 2012 The Mass of the Holy Spirit was concelebrated on Friday 4 May 2012 in the chapel of Mary MacKillop Place, North Sydney at 7 am. The President of Conference, Archbishop Philip Wilson, was the principal celebrant and preached the homily. The President welcomed the Apostolic Nuncio, Archbishop Giuseppe Lazzarotto who was warmly greeted. He concelebrated the opening Mass, met Bishops informally, addressed the Plenary Meeting and participated in a general discussion. Archbishop Denis Hart was elected President and Archbishop Philip Wilson was elected Vice-President. Page 1 of 7 The following elections were made to Bishops Conference commissions. (Chair of the Commission is highlighted in bold) 1.Administration and Information 7. Health and Community Services +Gerard Hanna +Don Sproxton +Michael McKenna +Terry Brady +Julian Porteous +Joseph Oudeman ofm cap +Les Tomlinson +David Walker 2.Canon Law 8. Justice, Ecology and Development +Brian Finnigan +Philip Wilson +Vincent Long ofm conv +Eugene Hurley +Philip Wilson +Greg O’Kelly sj +Chris Saunders 3. Catholic Education +Greg O’Kelly sj 9.Liturgy +Timothy Costelloe sdb +Mark Coleridge +James Foley +Peter Elliott +Gerard Holohan +Max Davis +Geoffrey Jarrett 4. Church Ministry +David Walker 10. Mission and Faith Formation +Peter Comensoli +Michael Putney +Peter Ingham +Peter Comensoli +Vincent Long ofm conv +Peter Ingham +Les Tomlinson +Julian Porteous +William Wright 11. Pastoral Life 5. Doctrine and Morals +Eugene Hurley +George Pell +Julian Bianchini +Mark Coleridge +Terry Brady +Tim Costelloe sdb +Anthony Fisher op +Anthony Fisher op +Gerard Hanna +Michael Kennedy 6. -

Issue 3, July 2016

Published by the DIOCESE OF BROOME PO Box 76, Broome WA 6725 T: 08 9192 1060 F: 08 9192 2136 FREE E-mail: [email protected] www.broomediocese.org ISSUE 3, JULY 2016 Multi-award winning magazine for the Kimberley • Building our future together Viewpoint The Jubilee - A Graced Time in Our Church When the Jubilee Mass began people representing the many communities of the Kimberley, processed into the Broome Civic Centre on June 2nd taking with them water from their home-towns and villages. With dignity and purpose they poured that water from their decorated containers into the large beautifully painted Holy Water Font Excellency, that rested at the foot of the sanctuary. Just Archbishop Adolfo Tito Yllana from as the waters mingled in that bowl to Canberra, and other bishops from Australia become one, so too were gathered as one COVER: and Bishop Cornelius Korir from Eldoret almost a thousand people from various parts Photo: M Adams Diocese in Kenya. It was indeed a time for of the vast Kimberley Mission and from Diocese of Broome Jubilee gratitude and celebration. I give thanks to outside the region too. They joined in Mass - 2 June 2016 almighty God for my forty years as a priest communion of mind and heart to celebrate Front, from left, Yeison Cruz, and my twenty years as Bishop of Broome Bishop Saunders and Fr with joy the fiftieth anniversary of the and the Kimberley, and I remembered those Marcello Parra Gonzalez Diocese of Broome. moments on our Jubilee night. To have Back, from left, Apostolic I am sure that the celebration of this been present as we celebrated the fiftieth Nuncio Archbishop Adolfo memorable Jubilee Eucharist exceeded our Tito Yllano, Archbishop of anniversary, the Golden Jubilee, of the greatest expectations and that is due in great Perth Timothy Costelloe SDB Diocese of Broome was an outstanding part to the wonderful work done in privilege for which I will always be thankful. -

Early Medieval G

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Religious Studies Faculty Publications Religious Studies 2001 History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval G. Scott aD vis University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/religiousstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Davis, G. Scott. "History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval." In Encyclopedia of Ethics, edited by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker, 709-15. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge, 2001. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval Copyright 2001 from Encyclopedia of Ethics by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker. Reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis, LLC, a division of Informa plc. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval ''Medieval" and its cognates arose as terms of op probrium, used by the Italian humanists to charac terize more a style than an age. Hence it is difficult at best to distinguish late antiquity from the early middle ages. It is equally difficult to determine the proper scope of "ethics," the philosophical schools of late antiquity having become purveyors of ways of life in the broadest sense, not clearly to be distin guished from the more intellectually oriented ver sions of their religious rivals. This article will begin with the emergence of philosophically informed re flection on the nature of life, its ends, and respon sibilities in the writings of the Latin Fathers and close with the twelfth century, prior to the systematic reintroduction and study of the Aristotelian corpus. -

The British Journal for the History of Science Mechanical Experiments As Moral Exercise in the Education of George

The British Journal for the History of Science http://journals.cambridge.org/BJH Additional services for The British Journal for the History of Science: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III FLORENCE GRANT The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 48 / Issue 02 / June 2015, pp 195 - 212 DOI: 10.1017/S0007087414000582, Published online: 01 August 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0007087414000582 How to cite this article: FLORENCE GRANT (2015). Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III. The British Journal for the History of Science, 48, pp 195-212 doi:10.1017/ S0007087414000582 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BJH, IP address: 130.132.173.207 on 07 Jul 2015 BJHS 48(2): 195–212, June 2015. © British Society for the History of Science 2014 doi:10.1017/S0007087414000582 First published online 1 August 2014 Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III FLORENCE GRANT* Abstract. In 1761, George III commissioned a large group of philosophical instruments from the London instrument-maker George Adams. The purchase sprang from a complex plan of moral education devised for Prince George in the late 1750s by the third Earl of Bute. Bute’s plan applied the philosophy of Frances Hutcheson, who placed ‘the culture of the heart’ at the foundation of moral education. To complement this affective development, Bute also acted on seventeenth-century arguments for the value of experimental philosophy and geometry as exercises that habituated the student to recognizing truth, and to pursuing it through long and difficult chains of reasoning. -

Sense and Sensibility

Nils Franzén Sense and Sensibility Four Essays on Evaluative Discourse Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Geijersalen, Thunbergsvägen 3H, Uppsala, Thursday, 20 September 2018 at 15:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Pekka Väyrynen (University of Leeds, Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Cultures ). Abstract Franzén, N. 2018. Sense and Sensibility. Four Essays on Evaluative Discourse. 37 pp. Uppsala: Department of Philosophy. ISBN 978-91-506-2717-6. The subject of this thesis is the nature of evaluative terms and concepts. It investigates various phenomena that distinguish evaluative discourse from other types of language use. Broadly, the thesis argues that these differences are best explained by the hypothesis that evaluative discourse serves to communicate that the speaker is in a particular emotional or affective state of mind. The first paper, “Aesthetic Evaluation and First-hand Experience”, examines the fact that it sounds strange to make evaluative aesthetic statements while at the same time denying that you have had first-hand experience with the object being discussed. It is proposed that a form of expressivism about aesthetic discourse best explains the data. The second paper, “Evaluative Discourse and Affective States of Mind”, discusses the problem of missing Moorean infelicity for expressivism. It is argued that evaluative discourse expresses states of mind attributed by sentences of the form “Nils finds it wrong to tell lies”. These states, the paper argues, are non-cognitive, and the observation therefore addresses the problem of missing infelicity. The third paper, “Sensibilism and Evaluative Supervenience”, argues that contemporary theories about why the moral supervenes on the non-moral have failed to account for the full extent of the phenomenon.