Peter Webster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Article by Dean Johnson

October 19, 1939 5c a Copy THE WITNESS HEWLETT JOHNSON The Dean of Canterbury Cathedral FIRST ARTICLE BY DEAN JOHNSON Copyright 2020. Archives of the Episcopal Church / DFMS. Permission required for reuse and publication. SCHOOLS CLERGY NOTES SCHOOLS BARTROP, F. F., formerly a master at St. Paul’s School,- Concord, N. H„ is now a tEije (General ©Jbeologrcal curate at the Advent, Boston. Ke m p e r TTTTT «■ Jibmm aru BREWSTER, WILLIAM, formerly curate at St. John’s. Waterbury, Conn., is now the KENOSHA. WISCONSIN rector of All Saints’, Belmont, Mass. Three-year undergraduate Episcopal Boarding and Day School. course of prescribed and elective CHIERA, GEORGE G., formerly rector of Trinity, Bridgewater, Mass., has accepted Preparatory to all colleges. Unusual study. the rectorship of St. Phillip’s, Wiscasset, opportunities in Art and Music. Fourth-year course for gradu Maine. Complete sports program. Junior ates, offering larger opportunity DAVIDSON, JAMES R., JR., recent gradu School. Accredited. Address: for specialization. ate of the Virginia Seminary, is now curate at All Saints’, Palo Alto, Calif., and in SISTERS OF ST. MARY Provision for more advanced charge of work with Episcopal students at Box W . T. work, leading to degrees of S.T.M. Stanford University. and D.Th. GIBBS, GEORGE C., has resigned charge of Kemper Hall Kenosha, Wisconsin Our Saviour, East Milton, Mass., to enter ADDRESS the Cowley Fathers. GILLEY, E. SPENCER, has resigned as vicar CATHEDRAL CHOIR SCHOOL THE DEAN of St. Stephen’s, Boston, because of illness. New York City GRANNIS, APPLETON, formerly rector of A boarding school for the forty boys of Chelsea Square New York City St. -

Science, Scientific Intellectuals and British Culture in the Early Atomic Age, 1945-1956: a Case Study of George Orwell, Jacob Bronowski, J.G

Science, Scientific Intellectuals and British Culture in The Early Atomic Age, 1945-1956: A Case Study of George Orwell, Jacob Bronowski, J.G. Crowther and P.M.S. Blackett Ralph John Desmarais A Dissertation Submitted In Fulfilment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy Imperial College London Centre For The History Of Science, Technology And Medicine 2 Abstract This dissertation proposes a revised understanding of the place of science in British literary and political culture during the early atomic era. It builds on recent scholarship that discards the cultural pessimism and alleged ‘two-cultures’ dichotomy which underlay earlier histories. Countering influential narratives centred on a beleaguered radical scientific Left in decline, this account instead recovers an early postwar Britain whose intellectual milieu was politically heterogeneous and culturally vibrant. It argues for different and unrecognised currents of science and society that informed the debates of the atomic age, most of which remain unknown to historians. Following a contextual overview of British scientific intellectuals active in mid-century, this dissertation then considers four individuals and episodes in greater detail. The first shows how science and scientific intellectuals were intimately bound up with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four (1949). Contrary to interpretations portraying Orwell as hostile to science, Orwell in fact came to side with the views of the scientific rig h t through his active wartime interest in scientists’ doctrinal disputes; this interest, in turn, contributed to his depiction of Ingsoc, the novel’s central fictional ideology. Jacob Bronowski’s remarkable transition from pre-war academic mathematician and Modernist poet to a leading postwar BBC media don is then traced. -

LP001061 0.Pdf

The James Lindahl Papers Papers, 1930s-1950s 29 linear feet Accession #1061 OCLC # DALNET # James Lindahl was born in Detroit in 1911. He served as Recording Secretary for the UAW-CIO Packard Local 190 and edited its newspaper in the 1930s and 1940s. Mr. Lindahl left the local in 1951 feeling that the labor movement no longer had a place for him. He earned a Master's degree from Wayne State University in Sociology in 1954 and later earned his living as a self-employed publisher in the Detroit area in various fields including retail, banking, and medicine. The James Lindahl Collection contains proceedings, reports, newspaper clippings, and election information pertaining to the UAW-CIO and its Packard Local 190 from the 1930s into the early 1950s. It also contains Mr. Lindahl's graduate school papers on local union membership and participation. The collection also contains publications, including pamphlets, books, periodicals, flyers and handbills, from many organizations such as the UAW, CIO, other labor unions and organizations, and the U.S. government from the 1930s into the early 1950s. Important subjects in the collection: UAW-CIO Packard Local 190 Union political activities Union leadership Ku Klux Klan Union membership Packard Motor Car Company 2 James Lindahl Collection CONTENTS 29 Storage Boxes Series I: General files, 1937-1953 (Boxes 1-6) Series II: Publications (Boxes 7-29) NON-MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL Approximately 12 union contracts and by-laws were transferred to the Archives Library. 3 James Lindahl Collection Arrangement The collection is arranged into two series. In Series I (Boxes 1-6), folders are simply listed by location within each box. -

Troublesome Priests: Christianity and Marxism in the Church of England, 1906-1969

Troublesome Priests: Christianity and Marxism in the Church of England, 1906-1969 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 Edward Poole School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents Abbreviations 3 Abstract 4 Declaration and Copyright Statement 5 Introduction: The Church of England and Marxism 6 “Proud Socialist Parson”: Robert William Cummings 29 Catholic Crusader: Conrad Noel 59 The Red Dean: Hewlett Johnson 91 A Priest in the Party: Alan Ecclestone 126 Conclusion 159 Bibliography 166 The total word count for this thesis is 48,575. 2 Abbreviations Alan Ecclestone Papers, Sheffield Archives AEP Christian Social Union CSU Church Socialist League CSL Conrad Noel Papers, Hull History Centre CNP Guild of St. Matthew GSM Hewlett Johnson Papers, University of Kent at Canterbury HJP Independent Labour Party ILP Labour History Archive and Study Centre, People’s History Museum LHA Lambeth Palace Library LPL Tameside Local Studies and Archives TLSA Working Class Movement Library WCML 3 Abstract This thesis argues that the relationship between Anglican Christianity and Marxism in Britain between 1906 and 1969 has been far more complex than is commonly understood. It is often assumed that the relationship between religious organisations and Marxism has often been acrimonious, the latter famously rejecting religion as the ‘opium of the people’, and religion resisting the revolutionary nature of Marxism. Taking a biographical approach, examining four Church of England clergymen, Robert Cummings, Conrad Noel, Hewlett Johnson and Alan Ecclestone, this thesis shows that some Anglicans saw a philosophical connection between Christianity and Marxism. -

An Online Bibliography 1859-2011

Anabaptism and Mission An Online Bibliography 1859-2011 Edited by Chad Mullet Bauman and James R. Krabill (First Edition) Revised and Updated by Joseph F. Pfeiffer Introduction to the Updated, Online Edition (2011) The following online electronic resource represents my efforts over the last few years, as a student at Associated Mennonite Biblical Seminary (AMBS), with the sponsorship and partnership of the AMBS Mission Studies Center, directed by Walter W. Sawatsky, to update the first print edition of this work: Anabaptism and Mission: A Bibliography, 1859-2000 (Elkhart, IN: Mennonite Mission Network, 2002), compiled and edited through the tremendous and tireless efforts of Chad M. Bauman and James R. Krabill. Throughout the ongoing project thus far, the researching and compiling of sources was a humbling task, as the body of bibliographic materials on this subject never remains static. Not only has the project entailed updating entries of authors and sources listed in the first edition, as well new authors and scholars that have come on the scene in the first decade of the 21 st century, but several more sources even from the 20th century were found and added, as the development of electronic communication and information technology has made a great deal more information and data available, even since the time of the first publication. Furthermore, the author has continued the trend of conceiving of Anabaptist as inherently broader than the mainline Mennonite denominations. Thus, including more materials from other Anabaptists traditions, such as the often over-looked Apostolic Christian tradition (see entries for Sheetz and Donais), as well as the Brethren in Christ Church, allows for the vision of a broader and more contextually diversified vision of Anabaptism to emerge, such as in contexts of the Amazon basin and New Guinea Highlands. -

Religious Self-Fashioning As a Motive in Early Modern Diary Keeping: the Evidence of Lady Margaret Hoby's Diary 1599-1603, Travis Robertson

From Augustine to Anglicanism: The Anglican Church in Australia and Beyond Proceedings of the conference held at St Francis Theological College, Milton, February 12-14 2010 Edited by Marcus Harmes Lindsay Henderson & Gillian Colclough © Contributors 2010 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. First Published 2010 Augustine to Anglicanism Conference www.anglicans-in-australia-and-beyond.org National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Harmes, Marcus, 1981 - Colclough, Gillian. Henderson, Lindsay J. (editors) From Augustine to Anglicanism: the Anglican Church in Australia and beyond: proceedings of the conference. ISBN 978-0-646-52811-3 Subjects: 1. Anglican Church of Australia—Identity 2. Anglicans—Religious identity—Australia 3. Anglicans—Australia—History I. Title 283.94 Printed in Australia by CS Digital Print http://www.csdigitalprint.com.au/ Acknowledgements We thank all of the speakers at the Augustine to Anglicanism Conference for their contributions to this volume of essays distinguished by academic originality and scholarly vibrancy. We are particularly grateful for the support and assistance provided to us by all at St Francis’ Theological College, the Public Memory Research Centre at the University of Southern Queensland, and Sirromet Wines. Thanks are similarly due to our colleagues in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Southern Queensland: librarians Vivienne Armati and Alison Hunter provided welcome assistance with the cataloguing data for this volume, while Catherine Dewhirst, Phillip Gearing and Eleanor Kiernan gave freely of their wise counsel and practical support. -

Canterbury Cathedral Trust Brochure

South Oculus Window Conserving ‘God’s eye’. Inspiring journeys... Canterbury Cathedral Trust The body is less a thing than a place; a location where things happen. Thought, feeling, memory and 8 The Precincts Canterbury Kent CT1 2EE Tel: +44 (0) 1227 865307 Fax: +44 (0) 1227 865327 anticipation filter through it sometimes staying but mostly passing on, like us in this great cathedral... Email: [email protected] www.canterbury-cathedral.org Transport Antony Gormley, Sculptor Patron: His Royal Highness The Duke of Kent Patron: (United States of America) President George H W Bush Registered Charity Number: 1112590 Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee: 5588837 Contents Message from the Dean Message from the Chairman, Development Committee Welcome to Canterbury Cathedral Planning for the Future Conserving the Fabric A Personal Perspective: Allan Willett CMG CVO A Precious Resource Preserving Treasures & Traditions Securing the Future How You Can Make a Difference Contact Us A Message from The Dean of Canterbury Insert Sheets: Canterbury Cathedral is a place of people – galvanising generations and continuing to hold a special place • Our Benefactors in hearts across the world today. A place of global significance, it is both the very cradle of English speaking • Our People Christianity, and a treasure house of history. The rich panorama of Romanesque and Gothic art and architecture – and the precious artefacts housed within – represent the cultural heritage and lives of many, past and present. • Gift Opportunities One need only visit to understand the awarding of UNESCO World Heritage Site status in 1988. • Stonemasonry The Cathedral and its Precincts remain a significant site of pilgrimage, ignited by the martyrdom of Archbishop • Stained Glass Thomas Becket in 1170. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Frontiers and borders : sources of transcendent credibility and the boundaries between political units Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/84b1t6kz Author Williamson, Rosco Publication Date 2007 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California i UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Frontiers and Borders: Sources of Transcendent Credibility and the Boundaries between Political Units A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Rosco Williamson Committee in charge: Professor David Mares, Chair Professor Alan Houston Professor Richard Madsen Professor Victor Magagna Professor Michael Monteon 2007 ii Copyright Rosco Williamson, 2007 All rights reserved iii The dissertation of Rosco Williamson is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2007 iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page...............................................................................................................iii Table -

Towards 'A Real Reunion'? Archbishop Aleksi Lehtonen's Efforts for Closer

“Towards ‘a real reunion’?” Schriften der Luther-Agricola-Gesellschaft 62 “Towards ‘a real reunion’?” Archbishop Aleksi Lehtonen’s efforts for closer relations with the Church of England 1945-1951 Mika K T Pajunen Luther-Agricola-Society Helsinki 2008 Luther-Agricola-Seura PL 33 (Aleksanterinkatu 7) FIN-00014 Helsingin yliopisto Finland Distributed by: Bookstore Tiedekirja Kirkkokatu 14 FIN-00170 Helsinki www.tiedekirja.fi © Mika K T Pajunen & Luther-Agricola-Seura ISBN 978-952-10-5143-2 (PDF) ISSN 1236-9675 Cover photo: Museovirasto KL 6.1.-87 Aleksi Lehtonen 1891- 1951. Valok. Tenhovaara Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy Jyväskylä 2008 Abstract This is an historical study of the relationship between the Church of Eng- land and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland during the archi- episcopate of Aleksi Lehtonen between 1945 and 1951. I have studied the relations of the churches from three perspectives: ecumenical; church politics; and political. The period begins with the aftermath of the visit of the Rev. H.M. Waddams to Finland in December 1944, and ends with the death of Archbishop Lehtonen at Easter 1951. The rhythm for the development of relations was set by the various visits between the churches. These highlight the development of relations from Waddams’ pro-Soviet agenda at the beginning of the period to the diametrically opposed attitude of Church of England visitors after the be- ginning of the Cold War. Official Church of England visitors to Finland were met by the highest political leadership alongside church leaders. The Finnish Church sought to use good relations with the Church of England as a means of gaining support and understanding for church and nation against the perceived Soviet threat, especially during the Finnish ”years of danger” from 1944 to 1948. -

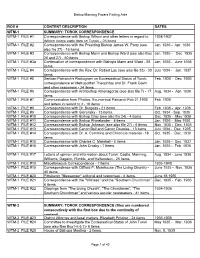

Bishop Manning Papers Finding Aide

Bishop Manning Papers Finding Aide BOX # CONTENT DESCRIPTION DATES WTM-1 SUMMARY: TOROK CORRESPONDENCE WTM-1 FILE #1 Correspondence with Bishop Wilson and other letters in regard to 1934-1937 Wilson (some early data on Torok) - 26 items. WTM-1 FILE #2 Correspondence with the Presiding Bishop James W. Perry (see Jan. 1936 - Apr. 1936 also file 27) - 16 items. WTM-1 FILE #3 Correspondence with Bishop Mann and Bishop Ward (see also files Jan. 1935 - Dec. 1935 26 and 27) - 50 items. WTM-1 FILE #3a Continuation of correspondence with Bishops Mann and Ward - 58 Jan. 1936 - June 1938 items. WTM-1 FILE #4 Correspondence with the Rev. Dr. Robert Lau (see also file 33) - 33 July 1934 - Jan. 1937 items. WTM-1 FILE #5 Serbian Patriarch's Radiogram on Ecclesiastical Status of Torok; Feb. 1936 - Dec. 1936 correspondence w/ Metropolitan Theophilus and Dr. Frank Gavin and other responses - 24 items. WTM-1 FILE #6 Correspondence with Archbishop Athenagoras (see also file 7) - 17 Aug. 1934 - Apr. 1936 items. WTM-1 FILE #7 Communication from Photios, Ecumenical Patriarch Feb 21,1936 Feb. 1936 and letters in regard to it - 18 items. WTM-1 FILE #8 Correspondence with Dr. Burgess - 21 items. Feb. 1936 - Apr. 1936 WTM-1 FILE #9 Correspondence with Gieronsky - 13 items. Oct. 1934 - Sep. 1936 WTM-1 FILE #10 Correspondence with Bishop Gray (see also file 24) - 4 items. Dec. 1935 - May 1936 WTM-1 FILE #11 Correspondence with Bishop Rhinelander - 4 items. Jan. 1936 - May 1936 WTM-1 FILE #12 Correspondence with Bishop Johnson (see also file 27) - 6 items Nov. -

The Soviet Union Today

AN OUTLINE STUDY 94?. 08+ A512^H THE AMERICAN RUSSIAN INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES THE SOVIET UNION TODAY An Outline Study Syllabus and Bibliography by The Staff of THE AMERICAN RUSSIAN INSTITUTE 56 WEST 45th STREET, NEW YORK, 19, N. Y. NEW YORK, 1943 Copyright 1943 by THE AMERICAN RUSSIAN INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, INC. 56 West 45th Street New York, 19, N. Y. Prepared by the Staff of The American Russian Institute: BERNARD L. KOTEN WILLIAM MANDEL JAMES P. MITCHELL HARRIET L. MOORE ROSE N. RUBIN Edited and Produced under union conditions; composed, printed and bound by union labor. BMU - UOPWA 18 CIO <*gi^*.@ ABCO PRESS INC * TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword (7) Purpose, Division of Time, Study Kit, Readings, Suggested Methods of Use (7). Chapter I. The Land and the People (8-15) Map of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, (8-9). I. Area and Population of the Sixteen Republics (9). II. The Peoples (10-12) ; Slavic (10), Turkic and Turco — Tatar (11), Transcaucasian (11), Iranian (11), Baltic (11), Finno-Ugrian (11), Mongol (11), Armenian (11), Jewish (11), German (11), Molda- vian (12), of the North (12). III. Physical Geography and Climate (12-15); Range (12), Vegetation (12), Economic Geography of European Russia (13), of the Urals (13), of Siberia (13), of the Far East (13), of the Caucasus (14), of Kazakhstan (14), of Central Asia (14), of the Arctic (15). Discussion Questions (15). Chapter II. The Historical Setting (16-23) Study Suggestions (16). I. Background for the Overthrow of Tsarism (16-17), the February Revolution (16). -

Left Pamphlet Collection

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: Special Collection Title: Left Pamphlet Collection Scope: A collection of printed pamphlets relating to left-wing politics mainly in the 20th century Dates: 1900- Extent: over 1000 items Name of creator: University of Sheffield Library Administrative / biographical history: The collection consists of pamphlets relating to left-wing political, social and economic issues, mainly of the twentieth century. A great deal of such material exists from many sources but, as such publications are necessarily ephemeral in nature, and often produced in order to address a particular issue of the moment without any thought of their potential historical value (many are undated), they are frequently scarce, and holding them in the form of a special collection is a means of ensuring their preservation. The collection is ad hoc, and is not intended to be comprehensive. At the end of the twentieth century, which was a period of unprecedented conflict and political and economic change around the globe, it can be seen that (as with Fascism) while the more extreme totalitarian Socialist theories based on Marxist ideology have largely failed in practice, despite for many decades posing a revolutionary threat to Western liberal democracy, many of the reforms advocated by democratic Socialism have been to a degree achieved. For many decades this outcome was by no means assured, and the process by which it came about is a matter of historical significance which ephemeral publications can help to illustrate. The collection includes material issued from many different sources, both collective and individual, of widely divergent viewpoints and covering an extensive variety of topics.