Anglicanism, Anti-Communism and Cold War Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

1962 the Witness, Vol. 47, No. 32

Tte WITN OCTOBER 4, 1962 publication. and reuse for required Permission DFMS. / Church Episcopal the of Archives 2020. Copyright CHURCH OF THE EPIPHANY, NEW YORK RECTOR HUGH McCANDLESS begins in this issue a series of three articles on a method of evangelization used in this parish. The drawing is by a parishioner, Richard Stark, M.D. SOME TEMPTATIONS OF THE CAMPUS SERVICES The Witness SERVICES In Leading Churches For Christ and His Church In Leading Churches THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH CHRIST CHURCH OF ST. JOHN THE DIVINE EDITORIAL BOARD Sunday: Holy Communion 7, 8, 9, 10; CAMBRIDGE, MASS. Morn ing Prayer, Holv Communion W. NORMAN PITTENGER, Chairman and Sermon, 11; Evensong and W. B. SPOFFORD SR., Managing Editor The Rev. Gardiner M. Day, Rector sermon, 4. CHARLES J. ADAMEK; O. SYDNEY BARR; LEE Sunday Services: 8:00, 9:30 and Morning Prayer and Holy Communion BELFORD; KENNETH R. FORBES; ROSCOE T. 11:15 a.m. Wed. and Holy Days: 7:15 (and 10 Wed.); Evensong, 5. FOUST; GORDON C. GRAHAM; ROBERT HAMP- 8:00 and 12:10 p.m. SHIRE; DAVID JOHNSON; CHARLES D. KEAN; THE HEAVENLY REST, NEW YORK GF-ORGE MACMURRAY; CHARLES MARTIN; CHRIST CHURCH, DETROIT 5th Avenue at 90th Street ROBERT F. MCGREGOR; BENJAMIN MINIFLE; SUNDAYS: Family Eucharist 9:00 a.m. J. EDWARD MOHR; CHARLES F. PENNIMAN; 976 East Jefferson Avenue Morning Praver and Sermon 11:00 •i m. (Choral Eucharist, first Sun- WILLIAM STRINGFELLOW; JOSEPH F. TITUS- The Rev. William B. Sperry, Rector 8 and 9 a.m. Holy Communion WEEKDAYS: Wednesdays: Holv Com- munion 7:30 a.m.; Thursdavs, Holy (breakfast served following 9 a.m. -

GS Misc 1095 GENERAL SYNOD the Dioceses Commission Annual

GS Misc 1095 GENERAL SYNOD The Dioceses Commission Annual Report 2014 1. The Dioceses Commission is required to report annually to the General Synod. This is its seventh report. 2. It consists of a Chair and Vice-Chair appointed by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York from among the members of the General Synod; four members elected by the Synod; and four members appointed by the Appointments Committee. Membership and Staff 3. The membership and staff of the Commission are as follows: Chair: Canon Prof. Michael Clarke (Worcester) Vice-Chair: The Ven Peter Hill (to July 2014) The Revd P Benfield (from November 2014) Elected Members: The Revd Canon Jonathan Alderton-Ford (St Eds & Ips) The Revd Paul Benfield (Blackburn) (to November 2014) Mr Robert Hammond (Chelmsford) Mr Keith Malcouronne (Guildford) Vacancy from November 2014 Appointed Members: The Rt Revd Christopher Foster, Bishop of Portsmouth (from March 2014) Mrs Lucinda Herklots The Revd Canon Dame Sarah Mullally, DBE Canon Prof. Hilary Russell Secretary: Mr Jonathan Neil-Smith Assistant Secretary: Mr Paul Clarkson (to March 2014) Mrs Diane Griffiths (from April 2014) 4. The Ven Peter Hill stepped down as Vice-Chair of the Commission upon his appointment as Bishop of Barking in July 2014. The Commission wishes to place on record their gratitude to Bishop Peter for his contribution as Vice-Chair to the Commission over the last three years. The Revd Paul Benfield was appointed by the Archbishops as the new Vice-Chair of the Commission in November 2014. 5. Mrs Diane Griffiths succeeded Paul Clarkson as Assistant Secretary to the Commission. -

1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours

12/19/2018 1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours The New Year Honours 1953 for the United Kingdom were announced on 30 December 1952,[1] to celebrate the year passed and mark the beginning of 1953. This was the first New Year Honours since the accession of Queen Elizabeth II. The Honours list is a list of people who have been awarded one of the various orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom. Honours are split into classes ("orders") and are graded to distinguish different degrees of achievement or service, most medals are not graded. The awards are presented to the recipient in one of several investiture ceremonies at Buckingham Palace throughout the year by the Sovereign or her designated representative. The orders, medals and decorations are awarded by various honours committees which meet to discuss candidates identified by public or private bodies, by government departments or who are nominated by members of the public.[2] Depending on their roles, those people selected by committee are submitted to Ministers for their approval before being sent to the Sovereign for final The insignia of the Grand Cross of the approval. As the "fount of honour" the monarch remains the final arbiter for awards.[3] In the case Order of St Michael and St George of certain orders such as the Order of the Garter and the Royal Victorian Order they remain at the personal discretion of the Queen.[4] The recipients of honours are displayed here as they were styled before their new honour, and arranged by honour, with classes (Knight, Knight Grand Cross, etc.) and then divisions (Military, Civil, etc.) as appropriate. -

Time for Reflection

All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group TIME FOR REFLECTION A REPORT OF THE ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY HUMANIST GROUP ON RELIGION OR BELIEF IN THE UK PARLIAMENT The All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group acts to bring together non-religious MPs and peers to discuss matters of shared interests. More details of the group can be found at https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm/cmallparty/190508/humanist.htm. This report was written by Cordelia Tucker O’Sullivan with assistance from Richy Thompson and David Pollock, both of Humanists UK. Layout and design by Laura Reid. This is not an official publication of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. It has not been approved by either House or its committees. All-Party Groups are informal groups of Members of both Houses with a common interest in particular issues. The views expressed in this report are those of the Group. © All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group, 2019-20. TIME FOR REFLECTION CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Recommendations 7 THE CHAPLAIN TO THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS 8 BISHOPS IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 10 Cost of the Lords Spiritual 12 Retired Lords Spiritual 12 Other religious leaders in the Lords 12 Influence of the bishops on the outcome of votes 13 Arguments made for retaining the Lords Spiritual 14 Arguments against retaining the Lords Spiritual 15 House of Lords reform proposals 15 PRAYERS IN PARLIAMENT 18 PARLIAMENT’S ROLE IN GOVERNING THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND 20 Parliamentary oversight of the Church Commissioners 21 ANNEX 1: FORMER LORDS SPIRITUAL IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 22 ANNEX 2: THE INFLUENCE OF LORDS SPIRITUAL ON THE OUTCOME OF VOTES IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS 24 Votes decided by the Lords Spiritual 24 Votes decided by current and former bishops 28 3 All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group FOREWORD The UK is more diverse than ever before. -

Welsh Disestablishment: 'A Blessing in Disguise'

Welsh disestablishment: ‘A blessing in disguise’. David W. Jones The history of the protracted campaign to achieve Welsh disestablishment was to be characterised by a litany of broken pledges and frustrated attempts. It was also an exemplar of the ‘democratic deficit’ which has haunted Welsh politics. As Sir Henry Lewis1 declared in 1914: ‘The demand for disestablishment is a symptom of the times. It is the democracy that asks for it, not the Nonconformists. The demand is national, not denominational’.2 The Welsh Church Act in 1914 represented the outcome of the final, desperate scramble to cross the legislative line, oozing political compromise and equivocation in its wake. Even then, it would not have taken place without the fortuitous occurrence of constitutional change created by the Parliament Act 1911. This removed the obstacle of veto by the House of Lords, but still allowed for statutory delay. Lord Rosebery, the prime minister, had warned a Liberal meeting in Cardiff in 1895 that the Welsh demand for disestablishment faced a harsh democratic reality, in that: ‘it is hard for the representatives of the other 37 millions of population which are comprised in the United Kingdom to give first and the foremost place to a measure which affects only a million and a half’.3 But in case his audience were insufficiently disheartened by his homily, he added that there was: ‘another and more permanent barrier which opposes itself to your wishes in respect to Welsh Disestablishment’, being the intransigence of the House of Lords.4 The legislative delay which the Lords could invoke meant that the Welsh Church Bill was introduced to parliament on 23 April 1912, but it was not to be enacted until 18 September 1914. -

Collection Name

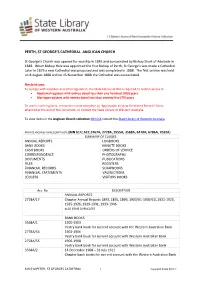

PERTH, ST GEORGE’S CATHEDRAL. ANGLICAN CHURCH St George’s Church was opened for worship in 1845 and consecrated by Bishop Short of Adelaide in 1848. When Bishop Hale was appointed the first Bishop of Perth, St George’s was made a Cathedral. Later in 1879 a new Cathedral was proposed and was completed in 1888. The first service was held on 8 August 1888 and on 15 November 1888 the Cathedral was consecrated. Restrictions To comply with adoption and other legislation, the State Library of WA is required to restrict access to Baptismal registers with entries dated less than one hundred (100) years Marriage registers with entries dated less than seventy five (75) years To access such registers, researchers must complete an 'Application to View Restricted Records' form, attached at the end of this document, or contact the State Library of Western Australia. To view items in the Anglican Church collection MN 614 contact the State Library of Western Australia PRIVATE ARCHIVES MANUSCRIPT NOTE (MN 614; ACC 2467A, 2778A, 3555A, 3568A, 6470A, 6786A, 7032A) SUMMARY OF CLASSES ANNUAL REPORTS LOGBOOKS BANK BOOKS MINUTE BOOKS CASH BOOKS ORDERS OF SERVICE CORRESPONDENCE PHOTOGRAPHS DOCUMENTS PUBLICATIONS FILES REGISTERS FINANCIAL RECORDS SCRAPBOOKS FINANCIAL STATEMENTS VALEDICTIONS LEDGERS VISITORS BOOKS Acc. No. DESCRIPTION ANNUAL REPORTS 2778A/17 Chapter Annual Reports 1893, 1895, 1899, 1900/01-1909/10, 1921-1923, 1925-1926, 1929-1931, 1933-1946. ALSO SOME DUPLICATES BANK BOOKS 3568A/1 1900-1903 Vestry bank book for current account with the Western Australian Bank 2778A/54 1903-1906 Vestry bank book for current account with Western Australian Bank 2778A/55 1906-1908 Vestry bank book for current account with Western Australian bank 3568A/2 14 December 1908 – 31 July 1911 Chapter bank books for current account with the Western Australian Bank MN 614 PERTH, ST GEORGES CATHEDRAL 1 Copyright SLWA ©2012 Acc. -

Frank Patrick Henagan a Life Well Lived

No 81 MarcFebruah 20ry 142014 The Magazine of Trinity College, The University of Melbourne Frank Patrick Henagan A life well lived Celebrating 40 years of co-residency Australia Post Publication Number PP 100004938 CONTENTS Vale Frank 02 Founders and Benefactors 07 Resident Student News 08 Education is the Key 10 Lisa and Anna 12 A Word from our Senior Student 15 The Southern Gateway 16 Oak Program 18 Gourlay Professor 19 New Careers Office 20 2 Theological School News 21 Trinity College Choir 22 Reaching Out to Others 23 In Remembrance of the Wooden Wing 24 Alumni and Friends events 26 Thank You to Our Donors 28 Events Update 30 Alumni News 31 Obituaries 32 8 10 JOIN YOUR NETWORK Did you know Trinity has more than 20,000 alumni in over 50 different countries? All former students automatically become members of The Union of the Fleur-de-Lys, the Trinity College Founded in 1872 as the first college of the University of Alumni Association. This global network puts you in touch with Melbourne, Trinity College is a unique tertiary institution lawyers, doctors, engineers, community workers, musicians and that provides a diverse range of rigorous academic programs many more. You can organise an internship, connect with someone for some 1,500 talented students from across Australia and to act as a mentor, or arrange work experience. Trinity’s LinkedIn around the world. group http://linkd.in/trinityunimelb is your global alumni business Trinity College actively contributes to the life of the wider network. You can also keep in touch via Facebook, Twitter, YouTube University and its main campus is set within the University and Flickr. -

Obituary of Sir James Darling

Obituary of Sir James Darling The Australian newspaper’s 3 November 1995 full-page obituary of Sir James Darling. The text is reproduced below. Click here to see enlargement*. Geelong’s master of inspiration Sir James Ralph Darling, OBE Headmaster of Geelong Grammar School, 1930-61. Chairman of the Australian Broadcasting Commission, 1961-67. Born Tonbridge, England, June 18, 1899. Died Melbourne, November 1, aged 96. ALTHOUGH James Ralph Darling, the second child of an Englishman, Augustine Major Darling, and his Scottish wife, Jane Baird, nee Nimmo, did not settle in Australia until he was nearly 30, he was to become a great Australian. Not only was he generally recognised as one, but he was also officially designated one of200 “Great Australians” in Australia’s Bicentennial year, 1988. Of the 200—22 then living—Darling was the only headmaster, public www.humancondition.com/darling-obituary * indicates a link 2 World Transformation Movement recognition there by being given to an exceptional, indeed unique, influence in the nation as an educator. It was as headmaster of Geelong Grammar School, an Anglican foundation dating from 1855 and, in his day, mainly a boarding school for boys, that he began to make his mark from 1930. He was educated at the preparatory school in Tonbridge run by his father, then at Repton, a boarding school in Derbyshire. After war and postwar service as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery in France and occupied Germany in 1918-19, he went to Oriel College, Oxford, where he read history. From 1921 to 1924 he taught in a rather tough school, Merchant Taylors’ in Liverpool, and then at one of the greater public schools, Charterhouse in Surrey, until his appointment to Geelong Grammar. -

For the Past 50 Years, Labour and Conservative

"For the past 50 years, Labour and Conservative Governments have shared a common agenda - stopping Home Rulers and Scottish Nationalists from breaking up Britain and making Scotland independent. This programme will show you how both parties have resorted to spying and underhand tactics to discredit the SNP, its members and supporters. We will show you how official documents which supported independence were kept hidden. Politicians and civil servants tried to obstruct independence and keep the country united." This document is a transcript, with some screen captures for illustrative purposes, of the Gaelic television programme 'DIOMHAIR' which was produced by the independent company - Caledonia TV. The transcription was carried out by a team of volunteers who regard the programme's content, which relies heavily on information released under FOI rules, as being of considerable educational value. Especially for those with a new or renewed interest in Scottish politics and its recent history. While most of the inevitable differences in text production (font type and size, spacings used etc.) stemming from individual preferences of team members have been homogenised by post editing, there is still noticeable variation in the layout, size, quality and frequency of the screen captures used to illustrate the text. If your interest is sparked by the contents of this document, we advise that you may obtain the original DVD for a more complete experience. It is available from: Caledonia TV, 147 Bath Street, Glasgow, for £10 plus p&p Some Explanatory Notes When Derek Mackay, the programme presenter, speaks, his words are in regular text and are not contained within quotation marks. -

First Article by Dean Johnson

October 19, 1939 5c a Copy THE WITNESS HEWLETT JOHNSON The Dean of Canterbury Cathedral FIRST ARTICLE BY DEAN JOHNSON Copyright 2020. Archives of the Episcopal Church / DFMS. Permission required for reuse and publication. SCHOOLS CLERGY NOTES SCHOOLS BARTROP, F. F., formerly a master at St. Paul’s School,- Concord, N. H„ is now a tEije (General ©Jbeologrcal curate at the Advent, Boston. Ke m p e r TTTTT «■ Jibmm aru BREWSTER, WILLIAM, formerly curate at St. John’s. Waterbury, Conn., is now the KENOSHA. WISCONSIN rector of All Saints’, Belmont, Mass. Three-year undergraduate Episcopal Boarding and Day School. course of prescribed and elective CHIERA, GEORGE G., formerly rector of Trinity, Bridgewater, Mass., has accepted Preparatory to all colleges. Unusual study. the rectorship of St. Phillip’s, Wiscasset, opportunities in Art and Music. Fourth-year course for gradu Maine. Complete sports program. Junior ates, offering larger opportunity DAVIDSON, JAMES R., JR., recent gradu School. Accredited. Address: for specialization. ate of the Virginia Seminary, is now curate at All Saints’, Palo Alto, Calif., and in SISTERS OF ST. MARY Provision for more advanced charge of work with Episcopal students at Box W . T. work, leading to degrees of S.T.M. Stanford University. and D.Th. GIBBS, GEORGE C., has resigned charge of Kemper Hall Kenosha, Wisconsin Our Saviour, East Milton, Mass., to enter ADDRESS the Cowley Fathers. GILLEY, E. SPENCER, has resigned as vicar CATHEDRAL CHOIR SCHOOL THE DEAN of St. Stephen’s, Boston, because of illness. New York City GRANNIS, APPLETON, formerly rector of A boarding school for the forty boys of Chelsea Square New York City St. -

Select List 38. Question Is Shall the Right Reverend Francis De Witt Batty, M. A., Bishop of Newcastle, Be P

Select List 38. Question is shall the Right Reverend Francis de Witt Batty, M. A., Bishop of Newcastle, be placed on the Select List? 39. Proposed by Rev Dr. Micklem, seconded by Mr C. H. G. Simpson, supported by Sir Albert Gould, Chancellor. 40. Vote taken. 41. The Right Reverend Francis de Witt Batty is not placed on the Select List. 42. The question is shall the Reverend Thomas Walter Gilbert, M.A., D.D., Principal of St. John's Hall, Highbury, be placed on the Select List? 43. Proposed by Archdeacon Charlton, seconded by Mr T. S. Holt. 44. Mr H. L. Tress said that information had been received that he is uncertain that he will even consider the nomination. 45. Vote taken. 46. The Reverend Dr. Gilbert is not placed on the Select List. 47. The question is shall the Reverend Arthur Rowland Harry Grant, D.D., C.V.O., M.V.O., Canon Residentiary in Norwich Cathedral, be placed on the Select List? 48. Proposed by Rev S. H. Denman, seconded by Mr H. L. Tress, supported by Rev Stanley Howard and Canon H. S. Begbie. 49. Vote taken. 50. The Rev Canon Grant, D.D., is placed on the Select List. 51. The question is, shall the Reverend Laurence William Grensted, D.D., Canon of Liverpool Cathedral, be placed on the Select List? 52. Proposed by Rev Dixon Hudson; seconded by Rev H. N. Baker; supported by Rev G. C. Glanville, Rev C.' T. Parkinson, Rev L. N. Sutton and Canon Garnsey. 53. Vote taken. 54.