The Persian Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Assyrian Period the Nee-Babylonian Period

and ready to put their ban and curse on any intruder. A large collection of administrative documents of the Cassite period has been found at Nippur. The Assyrian Period The names of the kings of Assyria who reigned in the great city of Nineveh in the eighth and seventh centuries until its total destruction in 606 B.C. have been made familiar to us through Biblical traditions concerning the wars of Israel and Juda, the siege of Samaria and Jeru- salem, and even the prophet Jonah. From the palaces at Calah, Nineveh, Khorsabad, have come monumental sculptures and bas-reliefs, historical records on alabaster slabs and on clay prisms, and the many clay tab- lets from the royal libraries. Sargon, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, Ashur- banipal- the Sardanapalus of the Greeks- carried their wars to Baby- lonia, to Elam, to the old Sumerian south on the shores of the Persian Gulf. Babylon became a province of the Assyrian Empire under the king's direct control, or entrusted to the hand of a royal brother or even to a native governor. The temples were restored by their order. Bricks stamped with the names of the foreign rulers have been found at Nip- pur, Kish, Ur and other Babylonian cities, and may be seen in the Babylonian Section of the University Museum. Sin-balatsu-iqbi was governor of Ur and a devoted servant of Ashurbanipal. The temple of Nannar was a total ruin. He repaired the tower, the enclosing wall, the great gate, the hall of justice, where his inscribed door-socket, in the shape of a green snake, was still in position. -

Melammu: the Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge

Melammu: The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Nina Ruge, Matthias Schemmel, Kai Surendorf Scientific Board Markus Antonietti, Antonio Becchi, Fabio Bevilacqua, William G. Boltz, Jens Braarvik, Horst Bredekamp, Jed Z. Buchwald, Olivier Darrigol, Thomas Duve, Mike Edmunds, Fynn Ole Engler, Robert K. Englund, Mordechai Feingold, Rivka Feldhay, Gideon Freudenthal, Paolo Galluzzi, Kostas Gavroglu, Mark Geller, Domenico Giulini, Günther Görz, Gerd Graßhoff, James Hough, Man- fred Laubichler, Glenn Most, Klaus Müllen, Pier Daniele Napolitani, Alessandro Nova, Hermann Parzinger, Dan Potts, Sabine Schmidtke, Circe Silva da Silva, Ana Simões, Dieter Stein, Richard Stephenson, Mark Stitt, Noel M. Swerdlow, Liba Taub, Martin Vingron, Scott Walter, Norton Wise, Gerhard Wolf, Rüdiger Wolfrum, Gereon Wolters, Zhang Baichun Proceedings 7 Edition Open Access 2014 Melammu The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Edited by Markham J. Geller (with the cooperation of Sergei Ignatov and Theodor Lekov) Edition Open Access 2014 Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Proceedings 7 Proceedings of the Sixth Symposium of the Melammu Project, held in Sophia, Bulgaria, September 1–3, 2008. Communicated by: Jens Braarvig Edited by: Markham J. Geller Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Beatrice Hermann, Linda Jauch -

ART. XVI.— the Early Commerce of Babylon with India— 700-300 B.C

JOURNAL THE EOYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. XVI.— The Early Commerce of Babylon with India— 700-300 B.C. By J. KENNEDY. LETTERS and coinage are the natural fruits of commerce. Scholars agree that the Indian or Brahma alphabet had a Western origin, and owed its existence to commercial exigencies. But while Hofrath Dr. Biihler traces it to a Phoenician source, and ascribes its creation to the early part of the eight century B.C., M. Halevy derives it from an Aramaean script in the time of Alexander the Great1 No such definite theory has been put forward with regard to the silver coins called puranas, the most ancient coins of India ; but it is generally believed that they were current before the Macedonian invasion, and, as silver has always been one of the most important of the imports from the West into India, we should naturally suppose that silver coinage came also from the West—unless, indeed, it were an indigenous invention.2 In the case, then, both of Indian letters and of Indian coinage, a direct and constant inter- course with Western Asia is the presupposition of every solution. ' Now, for a trade between Western Asia and 1 Vide Dr. Cust's interesting paper on the "Origin of the Phoenician and Indian Alphabets," J.R.A.S., January, 1897, pp. 62-5. 2 On the antiquity of the puranas, vide " Coins of Ancient India," by Sir A. Cunningham, pp. 52-3. London, 1891. J.B.A.S. 1898. • 16 Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. UCL, Institute of Education, on 08 Apr 2017 at 14:45:11, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

Chastised Rulers in the Ancient Near East

Chastised Rulers in the Ancient Near East Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree doctor of philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By J. H. Price, M.A., B.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Samuel A. Meier, Advisor Daniel Frank Carolina López-Ruiz Bill T. Arnold Copyright by J. H. Price 2015 Abstract In the ancient world, kings were a common subject of literary activity, as they played significant social, economic, and religious roles in the ancient Near East. Unsurprisingly, the praiseworthy deeds of kings were often memorialized in ancient literature. However, in some texts kings were remembered for criminal acts that brought punishment from the god(s). From these documents, which date from the second to the first millennium BCE, we learn that royal acts of sacrilege were believed to have altered the fate of the offending king, his people, or his nation. These chastised rulers are the subject of this this dissertation. In the pages that follow, the violations committed by these rulers are collected, explained, and compared, as are the divine punishments that resulted from royal sacrilege. Though attestations are concentrated in the Hebrew Bible and Mesopotamian literature, the very fact that the chastised ruler type also surfaces in Ugaritic, Hittite, and Northwest Semitic texts suggests that the concept was an integral part of ancient near eastern kingship ideologies. Thus, this dissertation will also explain the relationship between kings and gods and the unifying aspect of kingship that gave rise to the chastised ruler concept across the ancient Near East. -

357773-Sample.Pdf

Sample file THE BOOK OF RANDOM TABLES STEAMPUNKSample file CREDITS Written by Matt Davids Layout & Design by Matt Davids Cover & Interior Art by Albert Robida WWW.DICEGEEKS.COMSample file Contents copyright © 2021 dicegeeks. All rights reserved. All images in the public domain. GET MORE FREE RANDOM TABLES AT WWW.DICEGEEKS.COM/FREE Sample file TABLE OF CONTENTS How to Use this Book...................................................................................5 ITEMS & THINGS Airship Cargo................................................................................................7 Artifacts #1..............................................................................................8-9 Artifacts #2...........................................................................................10-11 Drugs and Medicines..................................................................................12 Items in a Desk...........................................................................................13 Items in a Scientist’s Lab.............................................................................14 Items in a Study..........................................................................................15 Steam Engine and Boiler Parts...................................................................16 Victorian Era Books #1...............................................................................18 Victorian Era Books #2..............................................................................19 FAMOUS VICTORIANS -

A Popular Handbook

A P O P UL AR HAN D B O O K A R Y S S Y I O L O G . A P O P ULAR HAN D B O O K OF USEFUL AND INTERESTING INFORMATION FOR BEGINNERS IN THE ELEMENTARY STUDY OF A Y R I L Y S S O O G . CO MP IL ED FR O M THE WR ITIN GS O F SO ME O F THE B EST AUTHO R ITIES F c . N R T . N O ! O . Price nett . P UB L ISHED B Y THE AUTH O R , . D I T.C H L I N G , SUSSEX 1 908 C O P YR I GHT . DEDICATION P f ss D . D . t . Sa c A. o th e R e v d . H y e ro e or b rm issi n , D edi cat ed y p e o t Wh m v ry m any ar gr at y at O xf o o e e e l o f As s yr i gy ord olo in th i a of Archa gy e r e rly a s w th e s d eolo i b t for h vin g o n ee nde ed i t i t in t r s t k m s f tak an n ell gen e e b m akin m any i y , e iv s th r y g l e el l e , e e b th e n ew and v r at th e W y e e 11 n ion s of old orld, C opy right . -

Babylon and Persia

MEDIA BABYLON AND PERSIA INCLUDING A STUDY OF THE ZEND-AVESTA OR RELIGION OF ZOROASTER FROM THE FALL OF NINEVEH TO THE PERSIAN WAR . ' ZENAIDE A. RAGOZIN MEHBEK OF THE "sOCIliT^ ETHNOI.OGIQUE " Of I'ARIS ; AUTHOR OF "aSSYHIA," *'cnALDEA," ETC. 3Lon&on T. FISHER UNWIN =6 PATERNOSTER SQUARE NEW YORK: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS ilDCCCLXXXlX ^ 5t^ ^' ^ ., " V',! p- ii!^ t \ ..H t k ARCHER-FRIEZE, IN GLAZED TILES ALONG THE PALACE OF DAREIOS I., AT SUSA EXHUMED BY MR. DIEULAFOY, IN I785. Frontispiece. MEDIA BABYLON AND PERSIA INCLUDING A STUDY OF THE ZEND-AVESTA OR RELIGION OF ZOROASTER FROM THE FALL OF NINEVEH TO THE PERSIAN WAR ZENAIDE A. RAGOZIN MEMBER OF THE " SOCIliTg ETH.NOI.OGIQUE " Of I'ARIS ; AUTHOR OF "ASSYRIA," " CHALDEA," ETC. 3Lon&on T. FISHER UNWIN 26 PATERNOSTER SQUARE NEW YORK: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MDCCCLXXXIX Entered at Stationers' Hall By T. Fisher Unwin C01.VRICHT ny G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1888 (For the United Slates of America) C(b^: ^ ^^ CLASSIFIED CONTENTS. Notable Religious Survival : the Parsis Anquetil Duperron .... 1-16 § I. The Parsis, descendants of the Persians and followers of Zoroaster.§ 2. The Parsis not heathens.§ 3. Con¬ quest of Persia by the Arabs.§ 4. Oppression and con¬ version of the country,§ 5. Self-exile of the Zoroastrians. § 6. Their wanderings and settlements in India. § 7. Principal tenets of their religion. § 8. Discovery of Parsi manuscripts.§ g. Anquetil Duperron and his mission. § 10. Hjs-departure for India.§ 11. Obstacles and hard¬ ships.§ 12. His translation of the Zend-Avesla.§ 13. He is attacked by William Jones.§ 14. -

The Religious Reform of Nabonidus: a Sceptical View

Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Proceedings 7 Kabalan Moukarzel: The Religious Reform of Nabonidus: A Sceptical View In: Markham J. Geller (ed.): Melammu : The Ancient World in an Age of Globalization Online version at http://edition-open-access.de/proceedings/7/ ISBN 978-3-945561-00-3 First published 2014 by Edition Open Access, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science under Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 Germany Licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/de/ Printed and distributed by: Neopubli GmbH, Berlin http://www.epubli.de/shop/buch/39410 The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Chapter 8 The Religious Reform of Nabonidus: A Sceptical View Kabalan Moukarzel 8.1 Introduction Modern scholars often ascribe to Nabonidus an attempt to introduce some sort of “religious reform.” Three documents were particularly important in the cre- ation of modern views on the reign of the last ruler of independent Babylonia– “The Verse Account of Nabonidus” (hereafter quoted as the Verse Account), “The Cyrus Cylinder” and “The Chronicle of Nabonidus.” The hypothesis that Naboni- dus was a “religious reformer” was based mainly on information from the Verse Account and the Cyrus Cylinder and was born with the first translations of these documents in the nineteenth century; subsequently, in the early twentieth cen- tury, it permeated the general notions on the reign of Nabonidus. Throughout the twentieth century this theory has remained indisputable for the majority of As- syriologists; however it was modified in some important details. -

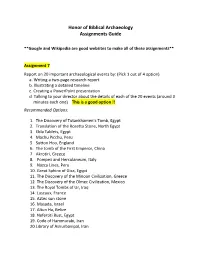

Honor of Biblical Archaeology Assignments Guide

Honor of Biblical Archaeology Assignments Guide **Google and Wikipedia are good websites to make all of these assignments** Assignment 7 Report on 20 important archaeological events by: (Pick 1 out of 4 option) a. Writing a two‐page research report b. Illustrating a detailed timeline c. Creating a PowerPoint presentation d. Talking to your director about the details of each of the 20 events (around 3 minutes each one) This is a good option !! Recommended Options: 1. The Discovery of Tutankhamen’s Tomb, Egypt 2. Translation of the Rosetta Stone, North Egypt 3. Ebla Tablets, Egypt 4. Machu Picchu, Peru 5. Sutton Hoo, England 6. The tomb of the First Emperor, China 7. Akrotiri, Greece 8. Pompeii and Herculaneum, Italy 9. Nazca Lines, Peru 10. Great Sphinx of Giza, Egypt 11. The Discovery of the Minoan Civilization, Greece 12. The Discovery of the Olmec Civilization, Mexico 13. The Royal Tombs of Ur, Iraq 14. Lascaux, France 15. Aztec sun stone 16. Masada, Israel 17. Altun Ha, Belize 18. Nefertiti Bust, Egypt 19. Code of Hammurabi, Iran 20. Library of Ashurbanipal, Iran Assignment 8 Share with a group or instructor the significance of each of these famous archaeologists: (3 minutes each) Have your notes on hand at the time of your report. a) Jean‐Francois Champollion b) Edward Robinson e) William Foxwell Albright Assignment 9 Assemble a folder with ten archaeological discoveries that have connected with the biblical history of the Old and New Testament (3 discoveries per page or one paragraph of each one of them) Handed over printed or by mail to your club director. -

Inscriptions

Price 50p INSCRIPTIONSINSCRIPTIONS The Newsletter of the Friends of the Egypt Centre, Swansea Issue 43 Notice of AGM The AGM of the Friends of the Egypt Centre September 2017 will be held on In this issue: Wednesday 11th October 2017 Notice of AGM 1 beginning at 6.30 pm in Forthcoming Lectures 1 Room 2, Fulton House Apep / Apopis – A demon of the All Friends are welcome and are Underworld 2 encouraged to attend. by Rachel Wollerton Editorial 3 New issue of Nile Magazine 3 Forthcoming Lectures from Jeff Burzacot Wednesday 13th September, 7 pm Bastet – Goddess of fertility and Dr Val Billingham sexuality 4 by Sophie McCloy Trustee of the Egypt Exploration Society and Independent Researcher Bes – a domestic deity 4 A Thousand Miles up the Nile: by Julia Smith Amelia Edwards' voyage of discovery Egyptian Hieroglyphs: In the winter of 1873-74, Amelia Edwards travelled up the Nile from a 12-week course with Cairo to Abu Simbel, a journey described in her 1876 bestseller, ªA Maiken Mosleth King 5 Thousand Miles up the Nileº. In this lecture, Val Billingham will Ancient Egypt in English draw on Amelia's own words and on images from the Egypt Literature 6 Exploration Society archive to tell the story of that seminal voyage. by Dulcie Engel Wednesday 11th October (7 pm, after AGM) “Wonderful Things” 9 by Dulcie Engel Dr Kasia Szpakowska Swansea University A Magical Mystery Tour through the Ancient Egyptian Afterlife with Ra Have you ever wondered what happened to the sun-god Ra when he set in the West each day? Come on a journey with him on his barque through each of the 12 hours of the Duat (the Afterlife). -

Acoustic Analysis Sogmatar

PreliminaryArchaeoacoustic Analysis of a Temple in the Ancient Site of Sogmatar in South-East Turkey Paolo Debertolis, Linda Eneix, Daniele Gullà PAOLO DEBERTOLIS, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Trieste (Italy), Chair of Dental Archaeology, Coordinator of Project SB Research Group(*) LINDA ENEIX, Mediterranean Institute of Ancient Civilizations, The OTS Foundation, United States and Malta DANIELE GULLA’, forensic researcher, Project SB Research Group, Bologna, Italy(*) (*) Note. SB Research Group (SBRG) is an international and interdisciplinary project team of researchers, researching the archaeoacoustic properties of ancient sites and temples throughout Europe ( www.sbresearchgoup.eu ). ABSTRACT - The archaeoacoustic properties and physical phenomena of a site in South East Anatolia (Turkey), described from ancient times as a religious and knowledge centre, were studied. An experiment of resonance and research of local physical phenomena by UV photography took place over one day to establish the properties of this underground site using SBSA protocol. The preliminary study found some interesting peculiarities that confirm a deep knowledge of resonance phenomenon at frequencies suspected to affect brain activity. On a side wall, we also identified a strong magnetic field that is without explanation. KEYWORDS: Archaeoacoustics, Sogmatar, Hypogeum, altered state of mind. Introduction Archaeoacoustics is a field of study complementary to archaeology, by which exploring sound behaviour of ancient ritual and ceremonial sites can bring a different dimension and understanding to the interpretation of their use. After six years of research at a number of sites throughout Europe, our group hypothesizes that the geographic location of cultic sites is not a random act, but rather driven by the geologic characteristics of that place. -

Introduction

1 Introduction The English word “museum” comes from the Latin word, and is pluralized as “museums” (or rarely, “musea”). It is originally from the Ancient Greek (Mouseion), which denotes a place or temple dedicated to the Muses (the patron divinities in Greek mythology of the arts), and hence a building set apart for study and the arts, especially the Musaeum (institute) for philosophy and research atAlexandria by Ptolemy I Soter about 280 BCE. The first museum/library is considered to be the one of Plato in Athens. However, Pausanias gives another place called “Museum,” namely a small hill in Classical Athens opposite the Akropolis. The hill was called Mouseion after Mousaious, a man who used to sing on the hill and died there of old age and was subsequently buried there as well. The Louvre in Paris France. 2 Museum The Uffizi Gallery, the most visited museum in Italy and an important museum in the world. Viw toward thePalazzo Vecchio, in Florence. An example of a very small museum: A maritime museum located in the village of Bolungarvík, Vestfirðir, Iceland showing a 19th-century fishing base: typical boat of the period and associated industrial buildings. A museum is an institution that cares for (conserves) a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic,cultural, historical, or scientific importance and some public museums makes them available for public viewing through exhibits that may be permanent or temporary. The State Historical Museum inMoscow. Introduction 3 Most large museums are located in major cities throughout the world and more local ones exist in smaller cities, towns and even the countryside.