THE APOCALYPTIC LANDSCAPES of LUDWIG MEIDNER By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zwischen Ideologie Und Kommerz

Zwischen Ideologie und Kommerz Der Kunstmarkt der DDR am Beispiel der Gegenwartskunst des Staatlichen Kunsthandels 1974 – 1990 Dissertation ur !rlangung des Grades eines Doktors der "hilosophie an der "hilosophischen #akult$t der %echnischen &ni'ersit$t Dresden 'orgelegt 'on Sa(ine %auscher ge() am 1*)1+)19,- in !isen(erg Betreuer. "ro/) Dr) 01rgen 21ller3 4nstitut /1r Kunst5 und 2usikwissenscha/t der %& Dresden Gutachter. 1) "ro/) Dr) 01rgen 21ller3 4nstitut /1r Kunst5 und 2usikwissenscha/t der %& Dresden +) "ro/) Dr) Bruno Klein3 4nstitut /1r Kunst5 und 2usikwissenscha/t der %& Dresden Eidesstattliche Erklärung 4ch 'ersichere hiermit3 dass ich die 'orgelegte Dissertation eigenst$ndig 'er/asst und keine anderen als die angege(enen 6il/smittel 'erwendet ha(e) 7rt3 Datum und &nterschri/t + Inhaltsverzeichnis I Einleitung .......................................................................................................................... 6 4)1 8or(emerkungen )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) 9 4)+ #orschungsstand ))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) +0 4)- 2ethode und :u/(au der :r(eit )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) +* II Kulturpolitischer Kontext ............................................................................................. 32 44)1 Die eitgen;ssische (ildende Kunst im So ialismus der 6onecker5<ra ))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) -

The Smart Museum of Art Bulletin 1992-1993

•vA THE SMART MUSEUM OF ART BULLETIN 1992-1993 IlliliMMil il I ' M- • tt. ,;i ii - v «<' S it *im •aw't .• • i';•. - 1 " h'f>•- vC-'"V „ <; • " - J& '"2 a., '%• > a a-ec •a: a- r / ' -aCaaT t: I • .•-.•a.' •a . 'aa •••'A. ;a . • . -a ' ' • ' a--a ' ., <J.. •a'; •T.,a- > ' ' ;• a• • a.• ,-vti a -"a .--yj ,v-5 _ - . -y y y>-" a- a "!> ' T'a- a; "a W aal'llfii^S Sip T' - ,, ' '• Vv,'-a-. • » «" ' " #liSIa. a . , "a ' • " v>:; • - a •" • « \ aa... a a:,"a• c'.Va. • a a - ' " V> '• B ',•• • - ; -/> a-~aVa .va . , - ••'". ..a aa-.a,aaa/:v s^gM. Ma ilgfi - - < .-k u. ' .>1'. ••.•-.a... a'a •. • ;y ... ,- a-, ^.-a, .-Car x t - ••- >a "V; a - ; a .- -a" ''•.. B >s - m' Hi *«•.. I I ft • •'- "'fa «'•«»•- , V.-Ss - - ' v- •••"••• r t- . - §• BSA'.v.^s^i a* • T a... • THE DAVID AND ALFRED SMART MUSEUM OF ART THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO g§ THE SMART MUSEUM OF ART B U L L E T I N 1992-1993 THE DAVID AND ALFRED SMART MUSEUM OF ART THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CONTENTS Volume 4, 1992-1993. STUDIES IN THE PERMANENT COLLECTION Copyright ©1993 by The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Testament and Providence: Ludwig Meidner's Interior of1909 2 5550 South Greenwood Avenue, Stephanie D'Alessandro Chicago, Illinois, 60637. All rights reserved. ISSN: 1041-6005 Empathy and the Experience of "Otherness" in Max Pechsteins Depictions of Women: The Expressionist Search for Immediacy 12 David Morgan Photography Credits: pages 2-9, fig. 1, Jerry Kobylecky Museum Photography; Fig. -

Das 20. Jahrhundert 279

Das 20. Jahrhundert 279 Neueingänge: Kunst, Fotobücher, Varia Antiquariat Frank Albrecht · [email protected] 69198 Schriesheim · Mozartstr. 62 · Tel.: 06203/65713 Das 20. Jahrhundert 279 D Verlag und A S Neueingänge: Kunst, Fotobücher, Varia Antiquariat 2 Frank 0. J Albrecht A Inhalt H R Kunst ............................................................................... 1 H Fotobücher .................................................................... 35 69198 Schriesheim U Varia .............................................................................. 44 Mozartstr. 62 N Register ......................................................................... 47 Tel.: 06203/65713 D FAX: 06203/65311 E Email: R [email protected] T Die Abbildung auf dem Vorderdeckel USt.-IdNr.: DE 144 468 306 D Steuernr. : 47100/43458 zeigt eine Original-Farblithographie A von Pablo Picasso (Katalognr. 207) S 2 0. J A H Spezialgebiete: R Autographen und H Widmungsexemplare U Belletristik in Erstausgaben N Illustrierte Bücher D Judaica Kinder- und Jugendbuch E Kulturgeschichte R Kunst T Unser komplettes Angebot im Internet: Politik und Zeitgeschichte Russische Avantgarde http://www.antiquariat.com Sekundärliteratur D und Bibliographien A S Gegründet 1985 2 0. Geschäftsbedingungen J Mitglied im Alle angebotenen Bücher sind grundsätzlich vollständig und, wenn nicht an- P.E.N.International A ders angegeben, in gutem Erhaltungszustand. Die Preise verstehen sich in Euro und im Verband H (€) inkl. Mehrwertsteuer. Das Angebot ist freibleibend; Lieferzwang besteht Deutscher Antiquare R nicht. Die Lieferungen sind zahlbar sofort nach Erhalt. Der Versand erfolgt auf H Kosten des Bestellers. Lieferungen können gegen Vorauszahlung erfolgen. Es besteht Eigentumsvorbehalt gemäß § 455 BGB bis zur vollständigen Bezah- U lung. Dem Käufer steht grundsätzlich ein Widerrufsrecht des Vertrages nach § Sparkasse Heidelberg N IBAN: DE87 6725 0020 361a BGB zu, das bei der Lieferung von Waren nicht vor dem Tag ihres Ein- 002 2013 13 D gangs beim Empfänger beginnt und ab dann 14 Tage dauert. -

The Silverman Collection

Richard Nagy Ltd. Richard Nagy Ltd. The Silverman Collection Preface by Richard Nagy Interview by Roger Bevan Essays by Robert Brown and Christian Witt-Dörring with Yves Macaux Richard Nagy Ltd Old Bond Street London Preface From our first meeting in New York it was clear; Benedict Silverman and I had a rapport. We preferred the same artists and we shared a lust for art and life in a remar kable meeting of minds. We were more in sync than we both knew at the time. I met Benedict in , at his then apartment on East th Street, the year most markets were stagnant if not contracting – stock, real estate and art, all were moribund – and just after he and his wife Jayne had bought the former William Randolph Hearst apartment on Riverside Drive. Benedict was negotiating for the air rights and selling art to fund the cash shortfall. A mutual friend introduced us to each other, hoping I would assist in the sale of a couple of Benedict’s Egon Schiele watercolours. The first, a quirky and difficult subject of , was sold promptly and very successfully – I think even to Benedict’s surprise. A second followed, a watercolour of a reclining woman naked – barring her green slippers – with splayed Richard Nagy Ltd. Richardlegs. It was also placed Nagy with alacrity in a celebrated Ltd. Hollywood collection. While both works were of high quality, I understood why Benedict could part with them. They were not the work of an artist that shouted: ‘This is me – this is what I can do.’ And I understood in the brief time we had spent together that Benedict wanted only art that had that special quality. -

Heinrich Zille's Berlin Selected Themes from 1900

"/v9 6a~ts1 HEINRICH ZILLE'S BERLIN SELECTED THEMES FROM 1900 TO 1914: THE TRIUMPH OF 'ART FROM THE GUTTER' THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Catherine Simke Nordstrom Denton, Texas May, 1985 Copyright by Catherine Simke Nordstrom 1985 Nordstrom, Catherine Simke, Heinrich Zille's Berlin Selected Themes from 1900 to 1914: The Trium of 'Art from the Gutter.' Master of Arts (Art History), May, 1985, 139 pp., 71 illustrations, bibliography, 64 titles. Heinrich Zille (1858-1929), an artist whose creative vision was concentrated on Berlin's working class, portrayed urban life with devastating accuracy and earthy humor. His direct and often crude rendering linked his drawings and prints with other artists who avoided sentimentality and idealization in their works. In fact, Zille first exhibited with the Berlin Secession in 1901, only months after Kaiser Wilhelm II denounced such art as Rinnsteinkunst, or 'art from the gutter.' Zille chose such themes as the resultant effects of over-crowded, unhealthy living conditions, the dissolution of the family, loss of personal dignity and economic exploi tation endured by the working class. But Zille also showed their entertainments, their diversions, their excesses. In so doing, Zille laid bare the grim and the droll realities of urban life, perceived with a steady, unflinching gaze. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . S S S . vi CHRONOLOGY . xi Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 5 . 1 II. AN OVERVIEW: BERLIN, ART AND ZILLE . 8 III. "ART FROM THE GUTTER:" ZILLE'S THEMATIC CHOICES . -

German and Austrian Art of the 1920S and 1930S the Marvin and Janet Fishman Collection

German and Austrian Art of the 1920s and 1930s The Marvin and Janet Fishman Collection The concept Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) was introduced in Germany in the 1920s to account for new developments in art after German and Austrian Impressionism and Expressionism. Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub mounted an exhibition at the Mannheim Museum in 1925 under the title Neue Art of the1920s and1930s Sachlichkeit giving the concept an official introduction into modern art in the Weimar era of Post-World War I Germany. In contrast to impressionist or abstract art, this new art was grounded in tangible reality, often rely- ing on a vocabulary previously established in nineteenth-century realism. The artists Otto Dix, George Grosz, Karl Hubbuch, Felix Nussbaum, and Christian Schad among others–all represented in the Haggerty exhibi- tion–did not flinch from showing the social ills of urban life. They cata- logued vividly war-inflicted disruptions of the social order including pover- Otto Dix (1891-1969), Sonntagsspaziergang (Sunday Outing), 1922 Will Grohmann (1887-1968), Frauen am Potsdamer Platz (Women at Postdamer ty, industrial vice, and seeds of ethnic discrimination. Portraits, bourgeois Oil and tempera on canvas, 29 1/2 x 23 5/8 in. Place), ca.1915, Oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. café society, and prostitutes are also common themes. Neue Sachlichkeit artists lacked utopian ideals of the Expressionists. These artists did not hope to provoke revolutionary reform of social ailments. Rather, their task was to report veristically on the actuality of life including the ugly and the vulgar. Cynicism, irony, and wit judiciously temper their otherwise somber depictions. -

Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Hobbs, Mark (2010) Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2182/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930 Mark Hobbs BA (Hons), MA Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of History of Art Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow February 2010 Abstract This thesis examines the urban topography of Berlin’s working-class districts, as seen in the art, architecture and other images produced in the city between 1924 and 1930. During the 1920s, Berlin flourished as centre of modern culture. Yet this flourishing did not exist exclusively amongst the intellectual elites that occupied the city centre and affluent western suburbs. It also extended into the proletarian districts to the north and east of the city. Within these areas existed a complex urban landscape that was rich with cultural tradition and artistic expression. This thesis seeks to redress the bias towards the centre of Berlin and its recognised cultural currents, by exploring the art and architecture found in the city’s working-class districts. -

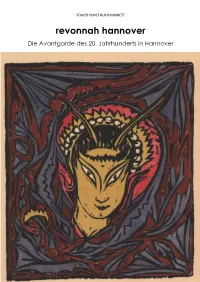

Revonnah Hannover Die Avantgarde Des 20

STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT revonnah hannover Die Avantgarde des 20. Jahrhunderts in Hannover 1 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT Katalog 3 Herbst 2018 Stader Kunst-Buch-Kabinett Antiquariat Michael Schleicher Schützenstrasse 12 21682 Hansestadt STADE Tel +49 (0) 4141 777 257 Email [email protected] Abbildungen Umschlag: Katalog-Nummern 67 und 68; Katalog-Nummer 32. Preise in EURO (€) Please do not hesitate to contact me: english descriptions available upon request. 2 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT 1 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Vorwort). I. Sonderausstellung Max Liebermann Gemälde Handzeichnungen. 1. Oktober - 5. November [1916]. Hannover, Königstr. 8. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1916, ca. 19,8 x 14,5 cm, (16) Seiten, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original-Klammerheftung. Umschlag etwas fleckig, Rückendeckel mit handschriftlichen Zahlenreihen, sonst ein gutes Exemplar. 280,-- Kestnerchronik 1, 29. - Schmied 1 (Abbildung des Umschlages Seite 238). - Literatur: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Hannover, Kunstverein, 1962. - Schmied, Wieland, Wegbereiter zur modernen Kunst, 50 Jahre Kestner Gesellschaft, 1966. - Kestnerchronik, Kestnergesellschaft, Buch 1, 2006. - REVONNAH, Kunst der Avantgarde in Hannover 1912-1933, Sprengel Museum, 2017. 2 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Text). III. Sonderausstellung Willy Jaeckel Gemälde u. Graphik. 17. Dezember 1916 - 17. Januar 1917. Hannover, Königstrasse 8. Zeitgleich mit Walter Alfred Rosam und Ludwig Vierthaler (Verzeichnis auf lose einliegendem Doppelblatt). Verkäufliche Arbeiten mit den gedruckten Preisangaben. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1917, ca. 19,7 x 14,4 cm, (16) Seiten, (4) Seiten Einlagefaltblatt als Ergänzung zum Katalog, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original- Klammerheftung (Klammern oxidiert). Im oberen Bereich alter Feuchtigkeitsschaden; die Seiten sind nicht verklebt. -

1914 the Avant-Gardes at War 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2014

1914 The Avant-Gardes at War 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2014 Media Conference: 7 November 2013, 11 a.m. Content 1. Exhibition Dates Page 2 2. Information on the Exhibition Page 4 3. Wall Quotations Page 6 4. List of Artists Page 11 5. Catalogue Page 13 6. Current and Upcoming Exhibitions Page 14 Head of Corporate Communications/Press Officer Sven Bergmann T +49 228 9171–204 F +49 228 9171–211 [email protected] Exhibition Dates Duration 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2013 Director Rein Wolfs Managing Director Dr. Bernhard Spies Curator Prof. Dr. Uwe M. Schneede Exhibition Manager Dr. Angelica C. Francke Dr. Wolfger Stumpfe Head of Corporate Communications/ Sven Bergmann Press Officer Catalogue / Press Copy € 39 / € 20 Opening Hours Tuesday and Wednesday: 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Public Holidays: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Closed on Mondays Admission 1914 and Missing Sons standard / reduced / family ticket € 10 / € 6.50 / € 16 Happy Hour-Ticket € 6 Tuesday and Wednesday: 7 to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 5 to 7 p.m. (for individuals only) Advance Ticket Sales standard / reduced / family ticket € 11.90 / € 7.90 / € 19.90 inclusive public transport ticket (VRS) on www.bonnticket.de ticket hotline: T +49 228 502010 Admission for all exhibitions standard / reduced / family ticket € 16/ € 11 / € 26.50 Audio Guide for adults € 4 / reduced € 3 in German language only Guided Tours in different languages English, Dutch, French and other languages on request Guided Group Tours information T +49 228 9171–243 and registration F +49 228 9171–244 [email protected] (ever both exhibitions: 1914 and Missing Sons) Public Transport Underground lines 16, 63, 66 and bus lines 610, 611 and 630 to Heussallee / Museumsmeile. -

The Cultivation of Class Identity in Max Beckmann's

THE CULTIVATION OF CLASS IDENTITY IN MAX BECKMANN’S WILHELMINE AND WEIMAR-ERA PORTRAITURE by Jaclyn Ann Meade A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2015 ©COPYRIGHT by Jaclyn Ann Meade 2015 All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION……...................................................................................................1 2. BECKMANN’S EARLY SELF-PORTRAITS ...............................................................8 3. FASHION AND BECKMANN’S MANNERISMS .....................................................11 Philosophical Fads and the Artist as Individual .............................................................27 4. BECKMANN’S IDENTITY AND SOCIAL POLITICS IN HIS MULTIFIGURAL WORK ............................................................................................33 5. BECKMANN AND THE NEW OBJECTIVITY..........................................................45 BIBILIOGRAPHY ..........................................................................................................125 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. Max Beckmann, Three Women in the Studio, 1908 .............................................2 2. Max Beckmann, Die Nacht, 1918 ........................................................................3 3. Max Beckmann, Self-Portrait with a Cigarette, 1923 .........................................3 4. Max Beckmann, Here is Intellect, 1921 ..............................................................3 -

Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: the Avant-Garde, No

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/raoulhausmannberOOOObens Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 55 Stephen C. Foster, Series Editor Associate Professor of Art History University of Iowa Other Titles in This Series No. 47 Artwords: Discourse on the 60s and 70s Jeanne Siegel No. 48 Dadaj Dimensions Stephen C. Foster, ed. No. 49 Arthur Dove: Nature as Symbol Sherrye Cohn No. 50 The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine Myroslava M. Mudrak No. 51 Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth- Century France Marilyn R. Brown No. 52 Emil Nolde and German Expressionism: A Prophet in His Own Land William S. Bradley No. 53 The Skyscraper in American Art, 1890-1931 Merrill Schleier No. 54 Andy Warhol’s Art and Films Patrick S. Smith Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada by Timothy O. Benson T TA /f T Research U'lVlT Press Ann Arbor, Michigan \ u » V-*** \ C\ Xv»;s 7 ; Copyright © 1987, 1986 Timothy O. Benson All rights reserved Produced and distributed by UMI Research Press an imprint of University Microfilms, Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Benson, Timothy O., 1950- Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. (Studies in the fine arts. The Avant-garde ; no. 55) Revision of author’s thesis (Ph D.)— University of Iowa, 1985. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Aesthetics. 2. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Political and social views. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release ' DRAWING IN AUSTRIA AND GERMANY Through October 1985 The current installation in the Drawings galleries at The Museum of Modern Art presents a comprehensive selection from the permanent collection of Austrian and German drawings and original works on paper. Organized by Bernice Rose, curator in the Department of Drawings, the installation reflects the development of drawing in Austria and Germany. Works by leading artists of this century are presented chronologically, beginning with drawings from the turn of the century and concluding with contemporary drawings. As Ms. Rose wrote in her introduction to the exhibition, "At the center of German drawing is Expressionism.... Expressionism, in the broad sense, has been used to describe the work of any artist who, rather than imitate the outer world of natural appearances, rejects or modifies it to reveal an inspired and imaginative inner world. In practice, Expressionist art employs the free and intuitive exaggeration of the everyday forms and colors of nature.... As a historian and colleague has noted, 'The individual attitudes of many of these artists who worked in Germany were fevered by passion, alternating exaltation and despair.'" The first section of DRAWING IN AUSTRIA AND GERMANY includes works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel who formed the group Die Brlicke (The Bridge) in 1905 with Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Die Brlicke was established in Dresden as the first organized reaction against Impressionism, which had become accepted by the conservative art establishment by 1905. Its members worked, exhibited, and published together in a boldly energetic and pioneering fashion.