The Smart Museum of Art Bulletin 1992-1993

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Silverman Collection

Richard Nagy Ltd. Richard Nagy Ltd. The Silverman Collection Preface by Richard Nagy Interview by Roger Bevan Essays by Robert Brown and Christian Witt-Dörring with Yves Macaux Richard Nagy Ltd Old Bond Street London Preface From our first meeting in New York it was clear; Benedict Silverman and I had a rapport. We preferred the same artists and we shared a lust for art and life in a remar kable meeting of minds. We were more in sync than we both knew at the time. I met Benedict in , at his then apartment on East th Street, the year most markets were stagnant if not contracting – stock, real estate and art, all were moribund – and just after he and his wife Jayne had bought the former William Randolph Hearst apartment on Riverside Drive. Benedict was negotiating for the air rights and selling art to fund the cash shortfall. A mutual friend introduced us to each other, hoping I would assist in the sale of a couple of Benedict’s Egon Schiele watercolours. The first, a quirky and difficult subject of , was sold promptly and very successfully – I think even to Benedict’s surprise. A second followed, a watercolour of a reclining woman naked – barring her green slippers – with splayed Richard Nagy Ltd. Richardlegs. It was also placed Nagy with alacrity in a celebrated Ltd. Hollywood collection. While both works were of high quality, I understood why Benedict could part with them. They were not the work of an artist that shouted: ‘This is me – this is what I can do.’ And I understood in the brief time we had spent together that Benedict wanted only art that had that special quality. -

German and Austrian Art of the 1920S and 1930S the Marvin and Janet Fishman Collection

German and Austrian Art of the 1920s and 1930s The Marvin and Janet Fishman Collection The concept Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) was introduced in Germany in the 1920s to account for new developments in art after German and Austrian Impressionism and Expressionism. Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub mounted an exhibition at the Mannheim Museum in 1925 under the title Neue Art of the1920s and1930s Sachlichkeit giving the concept an official introduction into modern art in the Weimar era of Post-World War I Germany. In contrast to impressionist or abstract art, this new art was grounded in tangible reality, often rely- ing on a vocabulary previously established in nineteenth-century realism. The artists Otto Dix, George Grosz, Karl Hubbuch, Felix Nussbaum, and Christian Schad among others–all represented in the Haggerty exhibi- tion–did not flinch from showing the social ills of urban life. They cata- logued vividly war-inflicted disruptions of the social order including pover- Otto Dix (1891-1969), Sonntagsspaziergang (Sunday Outing), 1922 Will Grohmann (1887-1968), Frauen am Potsdamer Platz (Women at Postdamer ty, industrial vice, and seeds of ethnic discrimination. Portraits, bourgeois Oil and tempera on canvas, 29 1/2 x 23 5/8 in. Place), ca.1915, Oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. café society, and prostitutes are also common themes. Neue Sachlichkeit artists lacked utopian ideals of the Expressionists. These artists did not hope to provoke revolutionary reform of social ailments. Rather, their task was to report veristically on the actuality of life including the ugly and the vulgar. Cynicism, irony, and wit judiciously temper their otherwise somber depictions. -

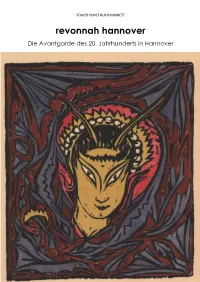

Revonnah Hannover Die Avantgarde Des 20

STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT revonnah hannover Die Avantgarde des 20. Jahrhunderts in Hannover 1 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT Katalog 3 Herbst 2018 Stader Kunst-Buch-Kabinett Antiquariat Michael Schleicher Schützenstrasse 12 21682 Hansestadt STADE Tel +49 (0) 4141 777 257 Email [email protected] Abbildungen Umschlag: Katalog-Nummern 67 und 68; Katalog-Nummer 32. Preise in EURO (€) Please do not hesitate to contact me: english descriptions available upon request. 2 STADER KUNST-BUCH-KABINETT 1 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Vorwort). I. Sonderausstellung Max Liebermann Gemälde Handzeichnungen. 1. Oktober - 5. November [1916]. Hannover, Königstr. 8. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1916, ca. 19,8 x 14,5 cm, (16) Seiten, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original-Klammerheftung. Umschlag etwas fleckig, Rückendeckel mit handschriftlichen Zahlenreihen, sonst ein gutes Exemplar. 280,-- Kestnerchronik 1, 29. - Schmied 1 (Abbildung des Umschlages Seite 238). - Literatur: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Hannover, Kunstverein, 1962. - Schmied, Wieland, Wegbereiter zur modernen Kunst, 50 Jahre Kestner Gesellschaft, 1966. - Kestnerchronik, Kestnergesellschaft, Buch 1, 2006. - REVONNAH, Kunst der Avantgarde in Hannover 1912-1933, Sprengel Museum, 2017. 2 Kestner Gesellschaft e. V. Küppers, P. E. (Text). III. Sonderausstellung Willy Jaeckel Gemälde u. Graphik. 17. Dezember 1916 - 17. Januar 1917. Hannover, Königstrasse 8. Zeitgleich mit Walter Alfred Rosam und Ludwig Vierthaler (Verzeichnis auf lose einliegendem Doppelblatt). Verkäufliche Arbeiten mit den gedruckten Preisangaben. Hannover, Druck von Edler & Krische, 1917, ca. 19,7 x 14,4 cm, (16) Seiten, (4) Seiten Einlagefaltblatt als Ergänzung zum Katalog, 4 schwarz-weiss Abbildungen, Original- Klammerheftung (Klammern oxidiert). Im oberen Bereich alter Feuchtigkeitsschaden; die Seiten sind nicht verklebt. -

1914 the Avant-Gardes at War 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2014

1914 The Avant-Gardes at War 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2014 Media Conference: 7 November 2013, 11 a.m. Content 1. Exhibition Dates Page 2 2. Information on the Exhibition Page 4 3. Wall Quotations Page 6 4. List of Artists Page 11 5. Catalogue Page 13 6. Current and Upcoming Exhibitions Page 14 Head of Corporate Communications/Press Officer Sven Bergmann T +49 228 9171–204 F +49 228 9171–211 [email protected] Exhibition Dates Duration 8 November 2013 – 23 February 2013 Director Rein Wolfs Managing Director Dr. Bernhard Spies Curator Prof. Dr. Uwe M. Schneede Exhibition Manager Dr. Angelica C. Francke Dr. Wolfger Stumpfe Head of Corporate Communications/ Sven Bergmann Press Officer Catalogue / Press Copy € 39 / € 20 Opening Hours Tuesday and Wednesday: 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Public Holidays: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Closed on Mondays Admission 1914 and Missing Sons standard / reduced / family ticket € 10 / € 6.50 / € 16 Happy Hour-Ticket € 6 Tuesday and Wednesday: 7 to 9 p.m. Thursday to Sunday: 5 to 7 p.m. (for individuals only) Advance Ticket Sales standard / reduced / family ticket € 11.90 / € 7.90 / € 19.90 inclusive public transport ticket (VRS) on www.bonnticket.de ticket hotline: T +49 228 502010 Admission for all exhibitions standard / reduced / family ticket € 16/ € 11 / € 26.50 Audio Guide for adults € 4 / reduced € 3 in German language only Guided Tours in different languages English, Dutch, French and other languages on request Guided Group Tours information T +49 228 9171–243 and registration F +49 228 9171–244 [email protected] (ever both exhibitions: 1914 and Missing Sons) Public Transport Underground lines 16, 63, 66 and bus lines 610, 611 and 630 to Heussallee / Museumsmeile. -

Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: the Avant-Garde, No

NUNC COCNOSCO EX PARTE THOMAS J BATA LIBRARY TRENT UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2019 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/raoulhausmannberOOOObens Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada Studies in the Fine Arts: The Avant-Garde, No. 55 Stephen C. Foster, Series Editor Associate Professor of Art History University of Iowa Other Titles in This Series No. 47 Artwords: Discourse on the 60s and 70s Jeanne Siegel No. 48 Dadaj Dimensions Stephen C. Foster, ed. No. 49 Arthur Dove: Nature as Symbol Sherrye Cohn No. 50 The New Generation and Artistic Modernism in the Ukraine Myroslava M. Mudrak No. 51 Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth- Century France Marilyn R. Brown No. 52 Emil Nolde and German Expressionism: A Prophet in His Own Land William S. Bradley No. 53 The Skyscraper in American Art, 1890-1931 Merrill Schleier No. 54 Andy Warhol’s Art and Films Patrick S. Smith Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada by Timothy O. Benson T TA /f T Research U'lVlT Press Ann Arbor, Michigan \ u » V-*** \ C\ Xv»;s 7 ; Copyright © 1987, 1986 Timothy O. Benson All rights reserved Produced and distributed by UMI Research Press an imprint of University Microfilms, Inc. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Benson, Timothy O., 1950- Raoul Hausmann and Berlin Dada. (Studies in the fine arts. The Avant-garde ; no. 55) Revision of author’s thesis (Ph D.)— University of Iowa, 1985. Bibliography: p. Includes index. I. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Aesthetics. 2. Hausmann, Raoul, 1886-1971—Political and social views. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release ' DRAWING IN AUSTRIA AND GERMANY Through October 1985 The current installation in the Drawings galleries at The Museum of Modern Art presents a comprehensive selection from the permanent collection of Austrian and German drawings and original works on paper. Organized by Bernice Rose, curator in the Department of Drawings, the installation reflects the development of drawing in Austria and Germany. Works by leading artists of this century are presented chronologically, beginning with drawings from the turn of the century and concluding with contemporary drawings. As Ms. Rose wrote in her introduction to the exhibition, "At the center of German drawing is Expressionism.... Expressionism, in the broad sense, has been used to describe the work of any artist who, rather than imitate the outer world of natural appearances, rejects or modifies it to reveal an inspired and imaginative inner world. In practice, Expressionist art employs the free and intuitive exaggeration of the everyday forms and colors of nature.... As a historian and colleague has noted, 'The individual attitudes of many of these artists who worked in Germany were fevered by passion, alternating exaltation and despair.'" The first section of DRAWING IN AUSTRIA AND GERMANY includes works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel who formed the group Die Brlicke (The Bridge) in 1905 with Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. Die Brlicke was established in Dresden as the first organized reaction against Impressionism, which had become accepted by the conservative art establishment by 1905. Its members worked, exhibited, and published together in a boldly energetic and pioneering fashion. -

THE APOCALYPTIC LANDSCAPES of LUDWIG MEIDNER By

THE APOCALYPTIC LANDSCAPES OF LUDWIG MEIDNER by CATHERINE COOK A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF RESEARCH, ART HISTORY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies The Barber Institute of Fine Arts The University of Birmingham Edgbaston Birmingham B15 2TS United Kingdom February 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis examines the apocalyptic landscape paintings of Ludwig Meidner (1884-1966), executed in Berlin between the years of 1911 and 1916. Meidner was an early adherent of the early generation of Expressionism. His creative project is, therefore, explored within the broader paradigm of German Expressionism. The apocalyptic landscapes are examined through a discussion of three themes: ideas of decline in German culture and Expressionist messianism, the experience of modernity and Meidner’s cityscape, and the apocalypse and revolution. Meidner and his contemporary Expressionist artists were influenced by a discourse which argued that German culture was in a state of decline and that artists were responsible for inciting its renewal. They were also a driving force of this discourse, interpreting its significance to be the messianic role of artists in the development of culture. -

The Apocalypse in Germany

The Apocalypse in Germany Klaus Vondung University of Missouri Press The Apocalypse in Germany The Apocalypse in Germany Klaus Vondung Translated from the German by Stephen D. Ricks University of Missouri Press Columbia and London © 1988 Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich/Germany © 2000 for the English language translation: Stephen D. Ricks © 2000 for the English language edition by The Curators of the University of Missouri University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States of America All rights reserved 54321 0403020100 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vondung, Klaus. [Apokalypse in Deutschland, English] The apocalypse in Germany / Klaus Vondung; translated from the German by Stephen D. Ricks. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8262-1292-1 (alk. paper) 1. Germany—History—Philosophy. 2. History (Theology) 3. Nationalism—Germany—History. 4. German literature—History and criticism. 5. Apocalyptic art—Germany. I. Title. DD97.V6613 2000 943'.001—dc21 00-032558 ⅜ϱ ™This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984. Text design: Elizabeth K. Young Jacket design: Susan Ferber Typesetter: BOOKCOMP, Inc. Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc. Typefaces: Helvetica, Goudy Old Style Frontispiece: Ludwig Meidner, Apocalyptic Landscape I (1912), © Ludwig Meidner-Archiv, Judisches¨ Museum der Stadt, Frankfurt am Main, 2000. This book is published with the generous assistance of the Eric Voegelin Institute in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Contents List of Illustrations vii Introduction 1 Part One: Approaches 1. How Exciting the Vision of the New World Is! Or, What Ernst Toller Connects with John of Patmos 11 2. -

Street View: the Expressive Face of the Public in James Ensor's 1888 Christ's Entry Into Brussels

© COPYRIGHT by Patricia L. Bray 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED STREET VIEW: THE EXPRESSIVE FACE OF THE PUBLIC IN JAMES ENSOR’S 1888 CHRIST’S ENTRY INTO BRUSSELS IN 1889 AND ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER’S 1913-15 STRASSENBILDER SERIES BY Patricia L. Bray ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes in tandem James Ensor’s 1888 Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s 1913-15 Strassenbilder series. Current interpretations of these paintings often emphasize a narrative reading of the artists’ personal expressions of the struggle of the individual against the angst and dysfunction of society. I explore the artists’ visualizations of the modern urban street and the individual in a crowd. In addition, I contextualize the environment of rapid modernization and fin-de-siècle anxiety, and the anti-institutionalism of Les XX and the Brücke. This thesis challenges the assumptions upon which current art-historical interpretations are constructed by examining the artists’ work within contemporary cultural discourse, crowd theory, and sociological scholarship, and through close visual readings of the artists’ formal strategies. I argue that Ensor and Kirchner deployed conscious aesthetic strategies in compositional distortion, antithesis and masquerade to explore the conflicting impulses, contumacy, and ambiguity of the modern moment. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express sincere gratitude to my thesis advisor, Professor Emerita Norma Broude, for her support, guidance, insight and inspiration. I would also like to express sincere appreciation to Professor Juliet Bellow for participating on my thesis committee and for her support of my academic endeavors. In addition, special thanks are due to the faculty in the Art History Department: Professor Helen Langa for her generous guidance in the production of this thesis, and Professor Kim Butler for her advice and intellectual inspiration. -

Annual Report 2002

2002 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D C. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Robert F. Erburu AUDIT COMMITTEE TRUSTEES' COUNCIL Sally Engelhard Pingree (as of 30 September 2002) Chairman (as of 30 September 2002) Diana C. Prince Robert F. Erburu Mitchell P. Rales Chairman Victoria P. Sant, Chair Catherine B. Reynolds Paul H. O'Neill La Salle D. Leffall Jr., Vice Chair Sharon Percy Rockefeller Robert H. Smith The Secretary of the Treasury Leon D. Black President Robert M. Rosenthal Robert H. Smith W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Roger W. Sant Julian Ganz, Jr. Calvin Cafritz B. Francis Saul II David 0. Maxwell William T. Coleman Jr. Thomas A. Saunders III Victoria P. Sant Edwin L. Cox Julian Ganz, Jr. Albert H. Small — James T. Dyke James S. Smith FINANCE COMMITTEE Mark D. Ein Ruth Carter Stevenson Edward E. Elson Roselyne C. Swig Robert H. Smith Doris Fisher Chairman Frederick A. Terry Jr. David 0. Maxwell Aaron I. Fleischman Paul H. O'Neill Joseph G. Tompkins Juliet C. Folger The Secretary of the Treasury John C. Whitehead John C. Fontaine Robert F. Erburu John Wilmerding Marina K. French Julian Ganz, Jr. Dian Woodner Morton Funger David 0. Maxwell Nina Zolt 1 Victoria P. Sant Lenore Greenberg Victoria P. Sant Rose Ellen Meyerhoff Greene EXECUTIVE OFFICERS ART AND EDUCATION Frederic C. Hamilton (as of 30 September 2002) COMMITTEE Richard C. Hedreen Teresa F. Heinz Robert H. Smith William H. Rehnquist i: Raymond J. Horowitz President The Chief Justice Robert H. Smith of the United States Chairman Robert J. Hurst Earl A. -

Report 2, by Dr Jill Lloyd Assessment of the Collection As a Key Asset In

Report 2, by Dr Jill Lloyd Assessment of the collection as a key asset in the worldwide understanding of German Expressionism Introduction Leicester City’s collection of German Expressionist Art plays a unique role in promoting the worldwide understanding of German Expressionism. Not only does it feature outstanding individual examples of German Expressionist art; it also includes an impressive range of artworks, in particular works on paper, which illuminate the history, background and development of the Expressionist movement. Although certain artists (such as August Macke) and certain representative works, which are present in the most important international collections of German Expressionism (particularly in Germany and the United States), are missing from the Leicester collection, this weakness is compensated for by the inclusion of émigré artists and women artists whose works are difficult to find elsewhere. The so-called ‘lost generation’ of German and Austrian émigré artists - including Martin Bloch, Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, Ernst Neuschul and Margarete Klopfleisch - is particularly well represented in Leicester by works in the permanent collection and important loans that contribute to the collection’s unique character. Moreover, although there are several museums in the United States (listed in section B) that have benefited from donations by German émigré collectors, Leicester is the only museum in the United Kingdom that has such deep historical links with major émigré collectors of German Expressionism, such as Albert, Tekla and Hans Hess, and Dr Rosa Schapire. From an international perspective, Leicester’s collection of German Expressionist art tells the story of émigré culture in the United Kingdom in a unique fashion, playing a vital role in our understanding of the reception and dissemination of the Expressionist movement, and preserving many works for posterity that might otherwise have fallen victim to the violent upheavals of twentieth-century history. -

German Expressionist Prints and the Legacy of the Early German Masters

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2019 Distorted Norms: German Expressionist Prints and the Legacy of the Early German Masters YOUNGCHUL SHIN University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation SHIN, YOUNGCHUL, "Distorted Norms: German Expressionist Prints and the Legacy of the Early German Masters" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 2253. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2253 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISTORTED NORMS: GERMAN EXPRESSIONSIT PRINTS AND THE LEGACY OF THE EARLY GERMAN MASTERS by Youngchul Shin A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2019 ABSTRACT DISTORTED NORMS: GERMAN EXPRESSIONIST PRINTS AND THE LEGACY OF THE EARLY GERMAN MASTERS by YoungChul Shin The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2019 Under the Supervision of Professor Sarah Schaefer German Expressionism, one of the most influential art movements of the twentieth century, was the source of unprecedented experiments in printmaking. Although the works appear modern to our eyes, Expressionist printmakers drew heavily from the early history of printmaking, which emerged in northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The early history of the print included the development of the woodcut, the innovation of the printing press, and the invention of new printmaking techniques such as engraving and drypoint.