The World's Religions After September 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ācārya Kundakunda's

Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine vkpk;Zizopulkj dqUndqUn fojfpr Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr izopulkj Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr izopulkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Charming black idol of Lord Pārśvanātha, the 7 twenty-third Tīrthańkara 1 in a Jain temple (Terāpanthī Kothī) at Shri Sammed Shikharji, y k. Jain, 20 Jharkhand, India. Pic Vija Ācārya Kundakunda’s Pravacanasāra – Essence of the Doctrine Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN: 978-81-932726-1-9 Rs. 600/- Published, in the year 2018, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ije iwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z 108 Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt vkxegh.kks le.kks .ksoIik.ka ija fo;k.kkfn A vfotk.karks vRFks [kosfn dEekf.k fd/ fHkD[kw AA & vkpk;Z dqUndqUn ^izopulkj* xkFkk 3&33 vFkZ & vkxeghu Je.k vkRek dks vkSj ij dks fu'p;dj ugha tkurk gS vkSj tho&vthokfn inkFkks± dks ugha tkurk gqvk eqfu leLr deks± dk {k; dSls dj ldrk gS\ vkpk;Z dqUndqUn dk ^izopulkj* okLro esa ,d cgqr gh egku xzUFk -

Ratnakarandaka-F-With Cover

Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-fourth Tīrthaôkara, Lord Mahāvīra, at the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, the holiest of Jaina pilgrimages, situated in Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-9-9 Rs. 500/- Published, in the year 2016, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ijeiwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt milxsZ nq£Hk{ks tjfl #tk;ka p fu%izfrdkjs A /ekZ; ruqfoekspuekgq% lYys[kukek;kZ% AA 122 AA & vkpk;Z leUrHkæ] jRudj.MdJkodkpkj vFkZ & tc dksbZ fu"izfrdkj milxZ] -

Full Complaint

Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 1 of 602 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ESTATE OF ROBERT P. HARTWICK, § HALEY RUSSELL, HANNAH § HARTWICK, LINDA K. HARTWICK, § ROBERT A. HARTWICK, SHARON § SCHINETHA STALLWORTH, § ANDREW JOHN LENZ, ARAGORN § THOR WOLD, CATHERINE S. WOLD, § CORY ROBERT HOWARD, DALE M. § HINKLEY, MARK HOWARD BEYERS, § DENISE BEYERS, EARL ANTHONY § MCCRACKEN, JASON THOMAS § WOODLIFF, JIMMY OWEKA OCHAN, § JOHN WILLIAM FUHRMAN, JOSHUA § CRUTCHER, LARRY CRUTCHER, § JOSHUA MITCHELL ROUNTREE, § LEIGH ROUNTREE, KADE L. § PLAINTIFFS’ HINKHOUSE, RICHARD HINKHOUSE, § SECOND AMENDED SUSAN HINKHOUSE, BRANDON § COMPLAINT HINKHOUSE, CHAD HINKHOUSE, § LISA HILL BAZAN, LATHAN HILL, § LAURENCE HILL, CATHLEEN HOLY, § Case No.: 1:18-cv-01612-CKK EDWARD PULIDO, KAREN PULIDO, § K.P., A MINOR CHILD, MANUEL § Hon. Colleen Kollar-Kotelly PULIDO, ANGELITA PULIDO § RIVERA, MANUEL “MANNIE” § PULIDO, YADIRA HOLMES, § MATTHEW WALKER GOWIN, § AMANDA LYNN GOWIN, SHAUN D. § GARRY, S.D., A MINOR CHILD, SUSAN § GARRY, ROBERT GARRY, PATRICK § GARRY, MEGHAN GARRY, BRIDGET § GARRY, GILBERT MATTHEW § BOYNTON, SOFIA T. BOYNTON, § BRIAN MICHAEL YORK, JESSE D. § CORTRIGHT, JOSEPH CORTRIGHT, § DIANA HOTALING, HANNA § CORTRIGHT, MICHAELA § CORTRIGHT, LEONDRAE DEMORRIS § RICE, ESTATE OF NICHOLAS § WILLIAM BAART BLOEM, ALCIDES § ALEXANDER BLOEM, DEBRA LEIGH § BLOEM, ALCIDES NICHOLAS § BLOEM, JR., VICTORIA LETHA § Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 2 of 602 BLOEM, FLORENCE ELIZABETH § BLOEM, CATHERINE GRACE § BLOEM, SARA ANTONIA BLOEM, § RACHEL GABRIELA BLOEM, S.R.B., A § MINOR CHILD, CHRISTINA JEWEL § CHARLSON, JULIANA JOY SMITH, § RANDALL JOSEPH BENNETT, II, § STACEY DARRELL RICE, BRENT § JASON WALKER, LELAND WALKER, § SUSAN WALKER, BENJAMIN § WALKER, KYLE WALKER, GARY § WHITE, VANESSA WHITE, ROYETTA § WHITE, A.W., A MINOR CHILD, § CHRISTOPHER F. -

Vkpk;Z Dqundqun Fojfpr Iapkflrdk;&Laxzg & Izkekf.Kd Vaxzsth O;K[;K Lfgr

Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr iapkfLrdk;&laxzg & izkekf.kd vaxzsth O;k[;k lfgr Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) vkpk;Z dqUndqUn fojfpr iapkfLrdk;&laxzg & izkekf.kd vaxzsth O;k[;k lfgr Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Viśuddhasāgara Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-third Tīrthaôkara, Lord Pārśvanātha at the ‘Svarõabhadra-kūÇa’, atop the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Kundakunda’s Paôcāstikāya-saÉgraha – With Authentic Explanatory Notes in English (The Jaina Metaphysics) Vijay K. Jain Non-copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original. ISBN: 978-81-932726-5-7 Rs. 750/- Published, in the year 2020, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971, Mob.: 9412057845, 9760068668 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun D I V I N E B L E S S I N G S eaxy vk'khokZn & ije iwT; fnxEcjkpk;Z 108 Jh fo'kq¼lkxj th eqfujkt oLrq ds oLrqRo dk HkwrkFkZ cks/ izek.k ,oa u; ds ekè;e ls gh gksrk gS_ izek.k ,oa u; ds vf/xe fcuk oLrq ds oLrqRo dk lR;kFkZ Kku gksuk vlaHko gS] blhfy, Kkuhtu loZizFke izek.k o u; dk xEHkhj vf/xe djrs gSaA u;&izek.k ds lehphu Kku dks izkIr gksrs gh lk/q&iq#"k -

Ten Universal Virtues

TEN UNIVERSAL VIRTUES SUPREME Munishri Ram Kumar Nandi Ten Universal Virtues Munishri Kam Kumar Nandi English Rendering by: Naresh Chandra Garg (Jain) M.A. (English & Hindi) Rtd. Vice Principal Senior-most English Lecturer J.V. Jain Inter College, Saharanpur Printed at: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29, Rajpur Road, Dehradun- 248 001 Ten Universal Virtues Munishri Kam Kumar Nandi Financiers: Shri Girnari Lal Chunni Lal Jain Chowk Fowara, Saharanpur Shri Sundar Lal Ramesh Chandra Jain Shaheed Ganj, Saharanpur Cost Price: Rs. 45/- Price for Mundane Souls: Utility First Edition: 1994, 1000 copies [c] All rights reserved Available at: Shri Vinod Jain V.K.J. Builders and Contractors (Pvt.) Ltd. 162/3/1, Rajpur Road, Dehradun 248 001 Tel: (0135) 623540, 28035 Shri Vivek Jain 229/1 Krishnapuri, Muzaffarnagar - 251 002 (U.P.) Tel: (0131) 26762 Typesetting and Printing at: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29, Rajpur Road, Dehradun -248 001 Tel: (0135) 28971 MUNISHRI 108 KAM KUMAR NANDI Monkshood Name Muni Kam Kumar Nandi Birth Place Village Khawat Kappa, Distt. Belgaum (Karnataka) Father’s Name Late Shri Bhimappa Mother’s Name Shrimati Ratnva Brothers Four brothers Sisters Three sisters Real Name Shri Bhramappa (fourth child of the family) Date of birth 6th June, 1967 Renunciation year November, 1988 Place of Celibacy Vow Ankloose (Maharastra) Celibacy Vow & Gandhar Acharya Shri Kunthu Sagarji Initiation ceremony by Place of Initiation Ceremony Holy mount Shri Sammed Shikher ji Teachers of Jain thought 1. Acharya Shri Vidhya Nand ji 2. Upadhaya Shri Kanak Nand ji Study of Languages Kannad, Hindi, English, Sanskrit, Prakrit, Marathi and Brahami script Daily Routine Constant meditation, incessant study (reading, writing, learning of sacred books), delivering sermons and religious discourse Up-to-date Chaturmas Under the supervision of Gandhar (Four-month rainy season Acharya Shri Kunthu Sagarji at Aara stay) (Bihar), Baraut (U.P.), Muzaffarnagar (U.P.), Rohtak Haryana) Under the supervision of Acarya Vidya Nand ji at Kundkund Bharati, New Delhi. -

North American Indians

INDIANS OF NORTH AMERICA • land boys and foreign tourists) along more AmericanIndianreligions emphasizedthe Mediterranean or pederastic lines will freedom of individuals to follow theirown develop. inclinations, as evidence of guidance from Apart from caste and family obli theirpersonalspiritguardian, and to share gations, however, Indian society is re generously what they had with others. markablytolerant of individualeccentrici Children's sexual play was more ties, and it is quite possible that when the likely to be regarded by adults as an amus curtainfinally liftsonIndian sexualityone ing activity rather than as a cause for may find the patterns ofhomosexualityin alarm. This casual attitude of child-rear India distinctively Indian. ingcontinued to influence people as they grew up, and even after their marriage. BIBLIOGRAPHY. Ejaz Ahmad, ulw Yet, while sex was certainly much more Relating to Sexual Offenses, 2nd ed., Allahabad: Ashoka Law House, 1975; J. accepted than in the Judeo-Christian tra P. Bhatnagar, Sexual Offenses, Al dition, it was not the major emphasis of lahabad: Ashoka Law House, 1987; Indian society. The focus was instead on Shakuntala Devi, The World ofHomo two forms of social relations: family sexuals, New Delhi: Vikas Publishing (making ties to other genders) and friend House, 1977; Serena Nanda, "The Hijras of India: Cultural and Individual ship (making ties within the samegender). Dimensions of an Institutionalized Third Since extremely close friendships were Gender Role," in Evelyn Blackwood, ed, emphasized between two "blood broth Anthl'Opology and Homosexual Behav ers" or two women friends, this allowed a ior, New York: Haworth Press, 1986, pp. context in which private homosexual 35-54; Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty, Women, Androgynes, and Other behavior could occur without attracting Mythical Beasts, Chicago: University of attention. -

Âcârya Pujyapada's

Âcârya Pujyapada’s IÈÇopadeúa – THE GOLDEN DISCOURSE vkpk;Z iwT;ikn fojfpr b"Vksins'k Foreword by: Âcârya 108 Vidyanand Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Âcârya Pujyapada’s IÈÇopadeúa – The Golden Discourse vkpk;Z iwT;ikn fojfpr b"Vksins'k Âcârya Pujyapada’s IÈÇopadeúa – The Golden Discourse vkpk;Z iwT;ikn fojfpr b"Vksins'k Foreword by: Âcârya 108 Vidyanand Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: The eye-catching, palm-size, black idol of ) 2 0 Lord Parshvanatha, the 23rd Tîrthaôkara, 0 2 ( n in Jain Temple, Jalalabad. i a J This antique idol is considered to be endowed . K y a with miraculous powers. Jalalabad is a small j i V historical town situated on Delhi-Saharanpur y b c i Road, 41 km from Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh. P Âcârya Pujyapada’s IÈÇopadeúa – The Golden Discourse Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission, provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-6-4 Rs. 450/- Published, in the year 2014, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) vk| ferk{kj vkpk;Z fo|kuUn eqfu dfo] oS;kdj.k vkSj nk'kZfud bu rhuksa O;fÙkQRoksa dk ,d=k leok; vkpk;Z nsoufUn&iwT;ikn esa ik;k tkrk gSA vkfniqjk.k ds jpf;rk vkpk;Z ftulsu us bUgas dfo;ksa esa rhFkZÑr fy[kk gS& dohuka rhFkZÑíso% ¯drjka r=k o.;Zrs A fonq"kka okÄ~eyèoafl rhFk± ;L; opkse;e~ AA1-52AA tks dfo;ksa -

Short Tender Call Notice

SHORT TENDER CALL NOTICE Sealed tender are invited for purchase of Books (Oriya and English) on different subjects for Biju Patnaik State Police Academy, Bhubaneswar. The approximate quantity required is noted against each. Titles of books, names of the Publisher and Writers are available in the Tender document and in our Website www.bpspaorissa.gov.in. Sl.No Name of the item Quantity 1 Library Books 1000 Approx. The Tender Document may be obtained on payment of Rs.200/- between 11 AM to 4 PM on each working day from the Office of the undersigned at the address given below. Tender document can also be obtained by sending a self stamped (Rs.75.00) envelop of size not less than 35cm x 25cm along with a demand draft of Rs.200/- payable at Bhubaneswar drawn in favour of the Director, BPSPA-cum-I.G. of Police, Training, Orissa, Bhubaneswar.Details of the documents/ specification and requirements may be down loaded from the Website of BPSPA i.e www.bpspaorissa.gov.in and sent along with a DD of Rs 200/- payable at BBSR in favour of Director, BPSPA-cum-IGP.Trg Orissa, Bhubaneswar. Bids submitted otherwise than the manner prescribed in the Tender document shall be rejected. Tender Calling authority has right to accept or reject the tender (s) without assigning any reason thereof. 1. Date of sale of Tender Document - 21.02.2011 ( between 10 AM to 5 PM on working days) 2. Last date of sale of Tender documents – 28.02.2011 3. Last date of receipt of Tender documents – 28.02.2011 4. -

Powers of Atman: 47 Shaktiyan As Described by Acharya Amritchandra

47 Powers of Soul 47 Shaktiyan as described by Acharya Amritchandra Dr Narayan Lal Kachhara With a Foreword and Summary by Dr Paras Mal Agrawal Publisher 1 Foreword I feel privileged to have an opportunity of writing a few words regarding the author and the subject matter of this publication. Dr. Narayan Lal Kachhara is a dedicated Jain scholar. It is his mission that the novel, valuable, and powerful concepts described by Jain Acharyas become available to English speaking community. By profession he is a Mechanical Engineer. This makes his writing concise and scientific. Earlier I came across his work on Karma Theory, Vargana, etc. But when he showed me this work on 47 Shaktiyan, then I realized that his interest in Adhyatmic aspect of Jainology can be valuable to all those who want to read Adhyatma in simple language. Samayasaar is the best work of Acharya Kundkund who is regarded as the most respectable Digambar Acharya of the modern fifth era. 1000 years after Acharya Kundkund, Acharya Amritchandra wrote the commentary on Samayasaar. It is known as Atmkhyati. The work of Dr. Kachhara presented here is based on the description given by Acharya Amritchandra in the appendix of Atmkhyati. In Atmkhyati, we find the narration of 47 Shaktiyan in about two pages just after Kalash number 263. For many, it may be very difficult to comprehend the two pages written by Acharya Amritchandra. Dr. Kachhara also got interested in this treasure only when he read the detailed explanation of Amritchandra’s work presented by Dr. Hukum Chand Bharill in Gyayak Bhava Prabodhini Hindi Tika of Samayasaar. -

Emissions Gap

Emissions Gap Emissions Gap Report 2020 © 2020 United Nations Environment Programme ISBN: 978-92-807-3812-4 Job number: DEW/2310/NA This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit services without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The United Nations Environment Programme would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Communication Division, United Nations Environment Programme, P. O. Box 30552, Nairobi 00100, Kenya. Disclaimers The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. For general guidance on matters relating to the use of maps in publications please go to http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/ htmain.htm Mention of a commercial company or product in this document does not imply endorsement by the United Nations Environment Programme or the authors. The use of information from this document for publicity or advertising is not permitted. Trademark names and symbols are used in an editorial fashion with no intention on infringement of trademark or copyright laws. -

Bhakti: a Bridge to Philosophical Hindus

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2000 Bhakti: A Bridge to Philosophical Hindus N. Sharath Babu Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Babu, N. Sharath, "Bhakti: A Bridge to Philosophical Hindus" (2000). Dissertation Projects DMin. 661. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/661 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT BHAKTI: A BRIDGE TO PHILOSOPHICAL HINDUS by N. Sharath Babu Adviser: Nancy J. Vyhmeister ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: BHAKTI: A BRIDGE TO PHILOSOPHICAL HINDUS Name of researcher: N. Sharath Babu Name and degree of faculty adviser: Nancy J. Vyhmeister, Ed.D. Date completed: September 2000 The Problem The Christian presence has been in India for the last 2000 years and the Adventist presence has been in India for the last 105 years. Yet, the Christian population is only between 2-4 percent in a total population of about one billion in India. Most of the Christian converts are from the low caste and the tribals. Christians are accused of targeting only Dalits (untouchables) and tribals. Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the nation, advised Christians to direct conversion to those who can understand their message and not to the illiterate and downtrodden. -

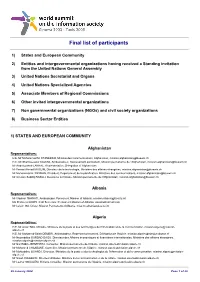

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies