Initial Interview Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Gunther

january 1934 Dollfuss and the Future of Austria John Gunther Volume 12 • Number 2 The contents of Foreign Affairs are copyrighted.©1934 Council on Foreign Relations, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution of this material is permitted only with the express written consent of Foreign Affairs. Visit www.foreignaffairs.com/permissions for more information. DOLLFUSS AND THE FUTURE OF AUSTRIA By John G?nther two VIRTUALLY unknown years ago, Dr. Engelbert Doll fuss has become the political darling of Western Europe. Two have seen him in the chambers years ago you might ? of the Austrian which he killed his parliament subsequently ? cherubic little face gleaming, his small, sturdy fists a-flutter career a and wondered what sort of awaited politician so per as as sonally inconspicuous. This year London and Geneva well Vienna have done him homage. Whence this sudden and dramatic are rise? Partly it derives from his personal qualities, which events considerable; partly it is because made him Europe's first a sort bulwark against Hitler, of Nazi giant-killer. And stature came to him paradoxically because he is four feet eleven inches high. Dollfuss was born a peasant and with belief in God. These are two facts paramount in his character. They have contributed much to his popularity, because Austria is three-fifths peasant, a with population 93 percent Roman Catholic. Much of his comes extreme personal charm and force from his simplicity of and amount to manner; his modesty directness almost na?vet?. no no Here is iron statue like Mustapha Kemal, fanatic evangelist a like Hitler. -

Harlan Cleveland Interviewer: Sheldon Stern Date of Interview: November 30, 1978 Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts Length: 56 Pages

Harlan Cleveland Oral History Interview—11/30/1978 Administrative Information Creator: Harlan Cleveland Interviewer: Sheldon Stern Date of Interview: November 30, 1978 Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts Length: 56 pages Biographical Note Cleveland, Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs (1961- 1965) and Ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (1965-1969), discusses the relationship between John F. Kennedy, Adlai E. Stevenson, and Dean Rusk; Stevenson’s role as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations; the Bay of Pigs invasion; the Cuban missile crisis; and the Vietnam War, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed February 21, 1990, copyright of these materials has passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

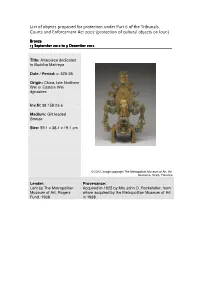

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Altarpiece dedicated to Buddha Maitreya Date / Period: c. 525-35 Origin: China, late Northern Wei or Eastern Wei dynasties Inv.N: 38.158.2a-e Medium: Gilt leaded Bronze Size: 59.1 x 38.1 x 19.1 cm © 2012. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Resource, Scala, Florence Lender: Provenance: Lent by The Metropolitan Acquired in 1925 by Mrs John D. Rockefeller, from Museum of Art, Rogers whom acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Fund, 1938 in 1938. List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Apollo Fountain Date / Period: 1532 Artist: Peter Flötner Inv.N: PL 1206/PL 0024 Medium: Brass Size: H. Incl. Base: 100 cm Base: 55 x 55 cm Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, Gemälde- und Skulpturensammlung Lender: Provenance: Leihgabe der Museen der Commissioned by the archers’ company for their Stadt Nürnberg, Gemälde- shooting yard, Herrenschiesshaus am Sand, und Skulpturensammlung Nuremberg; courtyard of the Pellerhaus. City Museum Fembohaus, Nuremberg (on permanent loan from the city of Nuremberg). List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Avalokiteshvara Date / Period: 9th- 10th century Origin: Java Inv.N: 509 Medium: Silvered Bronze Size: sculpture: 101 x 49 x 28 cm Base: 140 x 47 cm Weight: 250-300kgs Jakarta, Museum Nasional Indonesia Collection/Photo Feri Latief Lender: Provenance: National Museum Discovered in Tekaran, in Surakarta, Indonesia Indonesia (Philip Rawson, The Art of Southeast Asia, London, 1967, pp. -

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

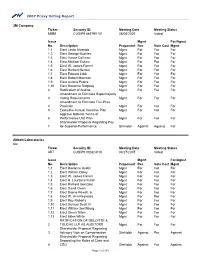

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making

Journal of Political Science Volume 33 Number 1 Article 2 November 2005 Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lasher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Lasher, Kevin J. (2005) "Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 33 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol33/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Madeleine Albright , Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lashe r Francis Marion University Women are finally becoming major participants in the U.S. foreign policy-making establishment . I seek to un derstand how th e arrival of women foreign policy-makers might influence the outcome of U.S. foreign polic y by fo cusi ng 011 th e activities of Mad elei n e A !bright , the first wo man to hold the position of Secretary of State . I con clude that A !bright 's gender did hav e some modest im pact. Gender helped Albright gain her position , it affected the manner in which she carried out her duties , and it facilitated her working relationship with a Repub lican Congress. But A !bright 's gender seemed to have had relatively little effect on her ideology and policy recom mendations . ver the past few decades more and more women have won election to public office and obtained high-level Oappointive positions in government, and this trend is likely to continue well into the 21st century. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

Hearings on the Nomination of Hon. Rich- Ard C. Holbrooke to Serve As Us Ambas

S. HRG. 106±225 HEARINGS ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. RICH- ARD C. HOLBROOKE TO SERVE AS U.S. AMBAS- SADOR TO THE UNITED NATIONS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 17, 22, AND 24, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57±735 CC WASHINGTON : 1999 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BILL FRIST, Tennessee STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director (II) CONTENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 1999 Page Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 4 Boxer, Barbara, U.S. Senator from California, prepared statement of ............... 34 Helms, Jesse, U.S. Senator from North Carolina, opening statement ................ 1 Holbrooke, Hon. Richard C., nominee to be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations .................................................................................................................. 10 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 16 Moynihan, Daniel Patrick, U.S. Senator from New York, statement ................. 9 Warner, John W., U.S. Senator from Virginia, statement ................................... 7 TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 1999 Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 47 Helms, Jesse, U.S. -

Guide to the John Gunther Papers 1935-1967

University of Chicago Library Guide to the John Gunther Papers 1935-1967 © 2006 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 9 Information on Use 9 Access 9 Citation 9 Biographical Note 9 Scope Note 10 Related Resources 12 Subject Headings 12 INVENTORY 13 Series I: Inside Europe 13 Subseries 1: Original Manuscript 14 Subseries 2: First Revision (Second Draft) 16 Subseries 3: Galley Proofs 18 Subseries 4: Revised Edition (October 1936) 18 Subseries 5: New 1938 Edition (November 1937) 18 Subseries 6: Peace Edition (October 1938) 19 Subseries 7: 1940 War Edition 19 Subseries 8: Published Articles by Gunther 21 Subseries 9: Memoranda 22 Subseries 10: Correspondence 22 Subseries 11: Research Notes-Abyssinian War 22 Subseries 12: Research Notes-Armaments 22 Subseries 13: Research Notes-Austria 23 Subseries 14: Research Notes-Balkans 23 Subseries 15: Research Notes-Czechoslovakia 23 Subseries 16: Research Notes-France 23 Subseries 17: Research Notes-Germany 23 Subseries 18: Research Notes-Great Britain 24 Subseries 19: Research Notes-Hungary 25 Subseries 20: Research Notes-Italy 25 Subseries 21: Research Notes-League of Nations 25 Subseries 22: Research Notes-Poland 25 Subseries 23: Research Notes-Turkey 25 Subseries 24: Research Notes-U.S.S.R. 25 Subseries 25: Miscellaneous Materials by Others 26 Series II: Inside Asia 26 Subseries 1: Original Manuscript 27 Subseries 2: Printer's Copy 29 Subseries 3: 1942 War Edition 31 Subseries 4: Printer's Copy of 1942 War Edition 33 Subseries 5: Material by Others 33 Subseries 6: -

COUNTRY PROFILE: MALI January 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Mali (République De Mali). Short Form: Mali. Term for Citi

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Mali, January 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: MALI January 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Mali (République de Mali). Short Form: Mali. Term for Citizen(s): Malian(s). Capital: Bamako. Major Cities: Bamako (more than 1 million inhabitants according to the 1998 census), Sikasso (113,813), Ségou (90,898), Mopti (79,840), Koutiala (74,153), Kayes (67,262), and Gao (54,903). Independence: September 22, 1960, from France. Public Holidays: In 2005 legal holidays in Mali include: January 1 (New Year’s Day); January 20 (Armed Forces Day); January 21* (Tabaski, Feast of the Sacrifice); March 26 (Democracy Day); March 28* (Easter Monday); April 21* (Mouloud, Birthday of the Prophet); May 1 (Labor Day); May 25 (Africa Day); September 22 (Independence Day); November 3–5* (Korité, end of Ramadan); December 25 (Christmas Day). Dates marked with an asterisk vary according to calculations based on the Islamic lunar or Christian Gregorian calendar. Flag: Mali’s flag consists of three equal vertical stripes of green, yellow, and red (viewed left to right, hoist side). Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: The area now constituting the nation of Mali was once part of three famed West African empires that controlled trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and other precious commodities. All of the empires arose in the area then known as the western Sudan, a vast region of savanna between the Sahara Desert to the north and the tropical rain forests along the Guinean coast to the south. All were characterized by strong leadership (matrilineal) and kin-based societies. -

The Library of the Musée National Des Arts Asiatiques Guimet (National Museum of Asian Arts, Paris, France)

Submitted on: June 1, 2013 Museum library and intercultural networking : the library of the Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet (National Museum of Asian Arts, Paris, France) Cristina Cramerotti Library and archives department, Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet, Paris, France [email protected] Copyright © 2013 by Cristina Cramerotti. This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Abstract: The Library and archives department of the musée Guimet possess a wide array of collections: besides books and periodicals, it houses manuscripts, scientific archives – both public and privates, photographic archives and sound archives. From the beginning in 1889, the library is at the core of research and communications with scholars, museums, and various cultural institutions all around the world, especially China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. We exchange exhibition catalogues and publications dealing with the museum collections, engage in joint editions of its most valuable manuscripts (with China), bilingual editions of historical documents (French and Japanese) and joint databases of photographs (with Japan). Every exhibition, edition or database project requires the cooperation of the two parties, a curator of musée Guimet and a counterpart from the institution we deal with. The exchange is twofold and mutually enriching. Since some years we are engaged in various national databases in order to highlight our collection: a collective library catalogue, the French photographic platform Arago, and of course Joconde, central database maintained by the Ministry of culture which documents the collections of the main French museums. Other databases are available on our website in cooperation with Réunion des musées nationaux, a virtual exposition on early Meiji Japan, and a database of Chinese ceramics. -

Press Kit Shangri-La Hotel, Paris

PRESS KIT SHANGRI-LA HOTEL, PARIS CONTENTS Shangri-La Hotel, Paris – A Princely Retreat………………………………………………..…….2 Remembering Prince Roland Bonaparte’s Historic Palace………………………………………..4 Shangri-La’s Commitment To Preserving French Heritage……………………………………….9 Accommodations………………………………………………………………………………...12 Culinary Experiences…………………………………………………………………………….26 Health and Wellness……………………………………………………………………………..29 Celebrations and Events………………………………………………………………………….31 Corporate Social Responsibility………………………………………………………………….34 Awards and Talent..…………………………………………………………………….…….......35 Paris, France – A City Of Romance………………………………………………………………40 About Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts……………………………………………………………42 Shangri-La Hotel, Paris – A Princely Retreat Shangri-La Hotel, Paris cultivates a warm and authentic ambience, drawing the best from two cultures – the Asian art of hospitality and the French art of living. With 100 rooms and suites, two restaurants including the only Michelin-starred Chinese restaurant in France, one bar and four historic events and reception rooms, guests may look forward to a princely stay in a historic retreat. A Refined Setting in the Heart of Paris’ Most Chic and Discreet Neighbourhood Passing through the original iron gates, guests arrive in a small, protected courtyard under the restored glass porte cochere. Two Ming Dynasty inspired vases flank the entryway and set the tone from the outset for Asia-meets-Paris elegance. To the right, visitors take a step back in time to 1896 as they enter the historic billiard room with a fireplace, fumoir and waiting room. Bathed in natural light, the hotel lobby features high ceilings and refurbished marble. Its thoughtfully placed alcoves offer discreet nooks for guests to consult with Shangri-La personnel. Imperial insignias and ornate monograms of Prince Roland Bonaparte, subtly integrated into the Page 2 architecture, are complemented with Asian influence in the decor and ambience of the hotel and its restaurants, bar and salons.