The Tough Way Back: Failed Migration in Mali1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

COUNTRY PROFILE: MALI January 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Mali (République De Mali). Short Form: Mali. Term for Citi

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Mali, January 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: MALI January 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Mali (République de Mali). Short Form: Mali. Term for Citizen(s): Malian(s). Capital: Bamako. Major Cities: Bamako (more than 1 million inhabitants according to the 1998 census), Sikasso (113,813), Ségou (90,898), Mopti (79,840), Koutiala (74,153), Kayes (67,262), and Gao (54,903). Independence: September 22, 1960, from France. Public Holidays: In 2005 legal holidays in Mali include: January 1 (New Year’s Day); January 20 (Armed Forces Day); January 21* (Tabaski, Feast of the Sacrifice); March 26 (Democracy Day); March 28* (Easter Monday); April 21* (Mouloud, Birthday of the Prophet); May 1 (Labor Day); May 25 (Africa Day); September 22 (Independence Day); November 3–5* (Korité, end of Ramadan); December 25 (Christmas Day). Dates marked with an asterisk vary according to calculations based on the Islamic lunar or Christian Gregorian calendar. Flag: Mali’s flag consists of three equal vertical stripes of green, yellow, and red (viewed left to right, hoist side). Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early History: The area now constituting the nation of Mali was once part of three famed West African empires that controlled trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and other precious commodities. All of the empires arose in the area then known as the western Sudan, a vast region of savanna between the Sahara Desert to the north and the tropical rain forests along the Guinean coast to the south. All were characterized by strong leadership (matrilineal) and kin-based societies. -

WFP Mali SPECIAL OPERATION SO 200521

WFP Mali SPECIAL OPERATION SO 200521 Country: Mali Type of project: Special Operation Title: Provision of Humanitarian Air Services in Mali Total cost (US$): US$ 4,516,235 Duration: Twelve months (1st January 2013 to 31st December 2013) Executive Summary This Special Operation (SO) is established to continue the provision of safe and reliable air transport services to the humanitarian community in Mali, and in the region, for 2013. Humanitarian Air Services in Mali started in March 2012 and were managed under the WFP/UNHAS Niger SO 200316. The initial plan was to operate from Niamey to northern Mali, but the change of the geopolitical situation in Mali and the closure of the north eastern part of the country necessitated the establishment of a separate UNHAS operational base in Bamako. From the 1st of January 2013, WFP/UNHAS Mali becomes a separate SO 200521 with its own management and structure. WFP/UNHAS Mali facilitates movement of United Nations agencies, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), government counterparts and donor representatives within Mali and between Mali and Niger. It also ensures air capacity for prompt evacuation of staff members to Bamako or abroad, in case of medical or security problems. This service is used by over 35 humanitarian agencies and the donor community currently operating in Mali. In 2013 WFP/UNHAS is planning to maintain a Beechcraft 1900 D (19 seats). An additional aircraft of the same type will be deployed on an ad-hoc basis to ensure uninterrupted services during maintenance of the main aircraft and/or to reinforce WFP/UNHAS capacity in case of additional needs. -

1. Characteristics of the Industry

In Senegal, Dakar Intl Airport Leopold Sedar SENGHOR is the main international airport, for which the current growth of Air Traffic is about 4 to 5%. Dakar ACC has the responsibility to provide air navigation services within Dakar FIR and Dakar Oceanic FIR where the major traffic flow is defined as the corridor Europe/South America. • The economical growth expected, with the great development of the tourism in the country in the near future will have an great impact on the Air Traffic growth which is projected around 7%. In addition, the creation of a new national airline will increase the domestic Air Traffic. • However, Dakar Intl Airport has just one single runway for the medium and heavy aircraft. The runway occupancy is too long because there is no rapid exit. • The airport is located in an urban area and the protection areas of the approach segments are occupied by buildings and houses. This situation doesn’t allow further extensions of the airport. That’s why the government has planned to build a new airport and to transfer the activities of Dakar Intl Airport to the new airport. • Meanwhile, the challenges are to maintain a satisfied level of safety and efficiency for the aerodrome operations in Dakar Intl Airport. • Senegal is a member state of ASECNA. In this regard, the air navigation services are provided by ASCECNA which is a regional organization with 17 African States members plus France. • ASECNA is an autonomous multinational entity governed politically by a committee of ministers and technically by a Board of Directors General of Civil Aviation Authority of the members states. -

MALI COUNTRY READER TABLE of CONTENTS Arva C. Floyd

MALI COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Arva C. Floyd 1960-1961 Officer in Charge of Senegal, Mali and Mauritania, Washington, DC Robert V. Keeley 1961-1963 Political Officer, Bamako Roscoe S. Suddarth 1961-1963 General Services Officer/Political Officer, Bamako Robert C. Haney 1962-1964 Political Affairs Officer, USIS, Bamako Phillip W. Pillsbury Jr. 1962-1964 Information Officer, USIA, Bamako Stephen Low 1963-1965 Guinea and Mali Desk Officer, Washington, DC John M. Anspacher 1964-1966 Public Affairs Office, USIS, Bamako C. Roberts Moore 1965-1968 Ambassador, Mali Mark C. Lissfeit 1967-1969 Economic-Commercial Officer, Bamako Harold E. Horan 1967-1969 Political Officer, Bamako Robert O. Blake 1970-1973 Ambassador, Mali Jay K. Katzen 1971-1973 Deputy Chief of Mission, Bamako Edward Brynn 1978-1982 Deputy Chief of Mission, Bamako Harold W. Geisel 1978-1980 Director, Joint Administrative Office, Bamako Keith L. Wauchope 1979-1981 Deputy Chief of Mission, Bamako Charles O. Cecil 1980-1982 Public Affairs Officer, Bamako Parker W. Borg 1981-1984 Ambassador, Mali Charles O. Cecil 1982-1983 Deputy Chief of Mission, Bamako ARVA C. FLOYD Officer in Charge of Senegal, Mali and Mauritania Washington, DC (1960-1961) Arva Floyd was born and raised in Georgia and educated at Emory University and the University of Edinburgh. After serving with the US Army in World War II and in the Occupying Forces in Austria after the war, he joined the Foreign Service and was posted to Djakarta, Indonesia in1952. His foreign postings include Indonesia, South Africa, Martinique and Brussels, where he dealt with matters concerning NATO, European Security and Disarmament. -

The Types of Missions Flown by Air America's Boeing 727S

AIR AMERICA: BOEING 727s by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 15 August 2003, last updated on 24 August 2015 The types of missions flown by Air America’s Boeing 727s: Although three Boeing 727s had been ordered by Air Asia, none of them was ever operated by Air America, but all of them were used by Southern Air Transport on an MAC contract. Connie Seigrist, one of the pilots who flew the 727s, recalls: “February 1967 – I left Intermountain Aviation of Marana, Arizona to rejoin the CAT Complex of the Agency to fly B-727’s of Southern Air Transport. All of my flying was in support of the Agency’s requirements in the area. Part of the flying was for the Korean troops, transportation to and from Korea to Vietnam. The flying was routine: Military personnel and cargo transportation. Enemy ground fire was always a threat on final when landing at Saigon or take-off at night from Da Nang. 3 January 1968 – My last flight into Da Nang flying a B-727 was slightly more than routine. I had arrived at night from Kadena. I went to Operations to file clearance and the Ops Officer said for us to move fast that the airfield would be under attack within an hour. I rushed the crew and asked the Officer to call traffic to have the aircraft off-loaded and loaded for departure immediately. We rushed to the aircraft for departure. […] As we turned for take-off, I saw the other end of the runway looking like a dozen fourth of July celebrations in one. -

A History of Teal. the Origins of Air New Zealand As an International Airline

University of Canterbury L. \ (' 1_.) THESIS PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY. by IoA. THOMSON 1968 A HISTORY OF TEALe THE ORIGINS OF AIR NEW ZEALAND AS AN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINEo 1940-1967 Table of Contents Preface iii Maps and Illustrations xi Note on Abbreviations, etco xii Chapter 1: From Vision to Reality. 1 Early airline developments; Tasman pioneers; Kingsford Smith's trans-Tasman company; Empire Air Mail Scheme and its extension to New and; conferences and delays; formation of TEAL. Chapter 2: The Flying-boat Era. 50 The inaugural flight; wartime operations - military duties and commercial services; post-war changes; Sandringham flying-boats; suspension of services; Solent flying boats; route expansion; withdrawal of flying-boats. Chapter 3: From Keels to Wheels. 98 The use of landplanes over the Tasman; TEAL's chartered landplane seryice; British withdrawal from TEAL; acquisition of DC-6 landplanes; route terations; the "TEAL Deal" and the purchase of Electras; enlarged route network; the possibility of a change in role and ownership. Chapter 4: ACquisition and Expansion. 148 The reasons for, and of, New Zealand's purchase of TEAL; twenty-one years of operation; Electra troubles; TEAL's new role; DC-8 re-equipment; the negotiation of traff rights; change of name; the widening horizons of the jet age .. Chapter 5: Conclusion .. 191 International airline developments; the advantages of New Zealand ownership of an international airline; the suggested merger of Air New" Zealand and NoAoC.; contemporary developments - routes and aircraft. Appendix A 221 Appendix B 222 Bibliography 223 Preface Flying as a means of travel is no more than another s forward in man's impulsive drive to discover and explore, to colonize and trade. -

Western-Built Jet and Turboprop Airliners

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS Data compiled from Flightglobal ACAS database flightglobal.com/acas EXPLANATORY NOTES The data in this census covers all commercial jet- and requirements, put into storage, and so on, and when airliners that have been temporarily removed from an turboprop-powered transport aircraft in service or on flying hours for three consecutive months are reported airline’s fleet and returned to the state may not be firm order with the world’s airlines, excluding aircraft as zero. shown as being with the airline for which they operate. that carry fewer than 14 passengers, or the equivalent The exception is where the aircraft is undergoing Russian aircraft tend to spend a long time parked in cargo. maintenance, where it will remain classified as active. before being permanently retired – much longer than The tables are in two sections, both of which have Aircraft awaiting a conversion will be shown as parked. equivalent Western aircraft – so it can be difficult to been compiled by Flightglobal ACAS research officer The region is dictated by operator base and does not establish the exact status of the “available fleet” John Wilding using Flightglobal’s ACAS database. necessarily indicate the area of operation. Options and (parked aircraft that could be returned to operation). Section one records the fleets of the Western-built letters of intent (where a firm contract has not been For more information on airliner types see our two- airliners, and the second section records the fleets of signed) are not included. Orders by, and aircraft with, part World Airliners Directory (Flight International, 27 Russian/CIS-built types. -

Atcm-Wp/13 Twelfth Meeting of the Afcac Air Transport

ATCM-WP/13 TWELFTH MEETING OF THE AFCAC AIR TRANSPORT COMMITTEE (Dakar, Senegal, 30-31October 2012) Theme: Sustainability of Air Transport Agenda Item 5: Air Carrier Ownership and Control RELAXING THE RULES FOR AIRLINE DESIGNATION AND AUTHORISATION AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE YD ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA (Presented by AFCAC) SUMMARY This paper provides Africa’s strategy for sustainability of air transport, through the harmonisation of the authorisation and designation of airlines based on a common set of criteria and the need for flexibility in order to facilitate African Airline access to international capital markets. The common set of criteria is based on the YD eligibility criteria. The benefit is to enable eligible African airlines the possibility to gain access to the international capital market, and also encourage cooperation via consolidation, mergers and acquisition as well as cross border investments. Action: Recommended action is stated in section 5 1. INTRODUCTION: 1.1 The substantial ownership and effective control provision, commonly found in ASA is not a provision of the Chicago Convention, but has its origin in the International Air Services Transit Agreement. Article I, Section 5 of the cited treaty establishes the right of each State to withhold or revoke a certificate or permit to an air transport enterprise of another State in any case where it is not satisfied that substantial ownership and effective control are vested in nationals of a contracting State. 1.2 With globalisation and liberalisation of the industry, in particular airline privatisation, alternative ownership and control models have emerged. The ICAO proposed clause for the designation of carriers however seem to be the most favoured (CONF/5-2003). -

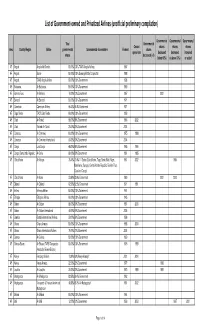

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Building Integrity in Mali's Defence and Security Sector

BUILDING INTEGRITY IN MALI’S DEFENCE AND SECURITY SECTOR An Overview of Institutional Safeguards. Transparency International (TI) is the world’s leading non-governmental anti-corruption organisation, addressing corruption and corruption risk in its many forms through a network of more than 100 national chapters worldwide. Transparency International Defence and Security (TI-DS) works to reduce corruption in defence and security worldwide. Author: Seán Smith Editors: Julien Joly, Matthew Steadman, Jo Johnston With thanks for feedback and assistance to: Ousmane Diallo Dr Karolina MacLachlan Stephanie Trapnell This report was funded by the United Nations Democracy Fund © 2019 Transparency International. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in parts is permitted, providing that full credit is given to Transparency International and provided that any such reproduction, in whole or in parts, is not sold or incorporated in works that are sold. Written permission must be sought from Transparency International if any such reproduction would adapt or modify the original content. Published October 2019.Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of October 2019. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. Transparency International UK’s registered charity number is 1112842. BUILDING INTEGRITY IN MALI’S DEFENCE AND SECURITY SECTOR: An Overview of the Institutional Safeguards. D Building Integrity in Mali’s Defence and Security Sector: An Overview of the Institutional Safeguards Transparency International Defence & Security 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Corruption is widely recognized as one of the fundamental drivers of conflict in Mali.