Provincial Ghetto in a Lens of Gentile Photographers Lucia Morawska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Pakn Treger Translation Issue

Table of Contents “You Have Not Betrayed Me Since the Day We Met” and “You Olive Tree in the Night” by Avrom Sutzkver, translated by Maia Evrona “On the Landing” by Yenta Mash, translated by Ellen Cassedy “From Eternity to Eternity: Thoughts and Considerations in Honor of Passover” by Moyshe Shtarkman, translated by Ross Perlin “In Which I Hate It and Can’t Stand It and Don’t Want to and Have No Patience at All” by Der Tunkeler, translated by Ri J. Turner “Letters” by H.D. Nomberg, translated by Daniel Kennedy “Blind Folye” by Froyim Kaganovski, translated by Beverly Bracha Weingrod “Mr. Friedkin and Shoshana: Wandering Souls on the Lower East Side” (an excerpt from Hibru) by Joseph Opatoshu, translated by Shulamith Z. Berger “Coney Island, Part Three” by Victor Packer, translated by Henry Sapoznik “Old Town” (an excerpt from The Strong and the Weak) by Alter Kacyzne, translated by Mandy Cohen and Michael Casper An Excerpt from “Once Upon a Time, Vilna” by Abraham Karpinowitz, translated by Helen Mintz “To a Fellow Writer” and “Shloyme Mikhoels” by Rachel H. Korn, translated by Seymour Levitan “The Destiny of a Poem” by Itzik Manger, translated by Murray Citron “The Blind Man” by Itsik Kipnis, translated by Joshua Snider Introduction he translation theorist Lawrence Venuti closes his short essay “How to Read a Translation” on a note of defiance: T Don’t take one translation of a foreign literature to be representative of the language, he tells us. Compare the translation to other translations from the same language. Venuti’s point is both political and moral. -

Touching the Memory

Touching the Memory By William Eaton Zeteo is Reading, September 2014 My father usually invited an oirech (a poor person) from among those who had lined up at the door of the Beit HaMidrash to join us for [a Sabbath] meal. These were itinerant beggars, of whom there were, unfortunately, many in Poland. I was fascinated by these vagabonds who lived at the margin of our society, and their presence at our table added excitement and mystery to the celebration. This from a memoir by the former rabbi and director of Harvard-Radcliffe Hillel, Ben-Zion Gold. In the Introduction, Gold says that he wrote this memoir, The Life of Jews in Poland before the Holocaust, to rectify an “imbalance in the way we remember the Jews of Europe.” That is, we focus on the Holocaust and ignore how Jews lived, the “vitality and richness of Jewish life” in Europe before the most deadly wave of anti-Semitism—and of mass murder of people of many backgrounds. (See, please, Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, and I would also here recommend Tzvetan Todorov’s La Conquête de l’Amérique: La question de l’autre — The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other — which speaks powerfully of human savagery on our side of the Atlantic.) That said, I must also note that Gold’s memoir came most to life for me in its antepenultimate chapter, which tells how he, unlike his parents and three sisters, escaped: avoided being murdered by the Germans. Reading this chapter I was reminded of how my William Eaton is the Editor of Zeteo. -

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Kelly. 2012. Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830349 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Kelly Scott Johnson All rights reserved Professor Ruth R. Wisse Kelly Scott Johnson Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin Abstract The thesis represents the first complete academic biography of a Jewish clockmaker, warrior poet and Anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard's experience was both typical and unique for a Jewish man of his era. It included four immigrations, two revolutions, numerous pogroms, a world war and, far less commonly, an assassination. The latter gained him fleeting international fame in 1926, when he killed the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura in Paris in retribution for pogroms perpetrated during the Russian Civil War (1917-20). After a contentious trial, a French jury was sufficiently convinced both of Schwarzbard's sincerity as an avenger, and of Petliura's responsibility for the actions of his armies, to acquit him on all counts. Mostly forgotten by the rest of the world, the assassin has remained a divisive figure in Jewish-Ukrainian relations, leading to distorted and reductive descriptions his life. -

Polish Jewry: a Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein

Polish Jewry: A Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein © YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 2013 The old castle and the Maharsha synagogue in Ostrog, connected by an underground passage. Built in the 17th century, the synagogue was named after Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer Eidels (1555 – 1631), author of the work Hidushei Maharsha. In 1795 the Jews of Ostrog escaped death by hiding in the synagogue during a military attack. To celebrate their survival, the community observed a special Purim each year, on the 7th of Tamuz, and read a scroll or Megillah which told the story of this miracle. Photograph by Alter Kacyzne. YIVO Archives. Courtesy of the Forward Association. A Haven from Persecution YIVO’s dedication to the study of the history of Jews in Poland reflects the importance of Polish Jewry in the Jewish world over a period of one thou- sand years, from medieval times until the 20th century. In early medieval Europe, Jewish communities flourished across a wide swath of Europe, from the Mediterranean lands and the Iberian Peninsu- la to France, England and Germany. But beginning with the first crusade in 1096 and continuing through the 15th century, the center of Jewish life steadily moved eastward to escape persecutions, massacres, and expulsions. A wave of forced expulsions brought an end to the Jewish presence in West- ern Europe for long periods of time. In their quest to find safe haven from persecutions, Jews began to settle in Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, and parts of Ukraine, and were able to form new communities there during the 12th through 14th centuries. -

Jewish Labor Bund's

THE STARS BEAR WITNESS: THE JEWISH LABOR BUND 1897-2017 112020 cubs בונד ∞≥± — A 120TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF THE FOUNDING OF THE JEWISH LABOR BUND October 22, 2017 YIVO Institute for Jewish Research at the Center for Jewish History Sponsors YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Jonathan Brent, Executive Director Workmen’s Circle, Ann Toback, Executive Director Media Sponsor Jewish Currents Executive Committee Irena Klepisz, Moishe Rosenfeld, Alex Weiser Ad Hoc Committee Rochelle Diogenes, Adi Diner, Francine Dunkel, Mimi Erlich Nelly Furman, Abe Goldwasser, Ettie Goldwasser, Deborah Grace Rosenstein Leo Greenbaum, Jack Jacobs, Rita Meed, Zalmen Mlotek Elliot Palevsky, Irene Kronhill Pletka, Fay Rosenfeld Gabriel Ross, Daniel Soyer, Vivian Kahan Weston Editors Irena Klepisz and Daniel Soyer Typography and Book Design Yankl Salant with invaluable sources and assistance from Cara Beckenstein, Hakan Blomqvist, Hinde Ena Burstin, Mimi Erlich, Gwen Fogel Nelly Furman, Bernard Flam, Jerry Glickson, Abe Goldwasser Ettie Goldwasser, Leo Greenbaum, Avi Hoffman, Jack Jacobs, Magdelana Micinski Ruth Mlotek, Freydi Mrocki, Eugene Orenstein, Eddy Portnoy, Moishe Rosenfeld George Rothe, Paula Sawicka, David Slucki, Alex Weiser, Vivian Kahan Weston Marvin Zuckerman, Michael Zylberman, Reyzl Zylberman and the following YIVO publications: The Story of the Jewish Labor Bund 1897-1997: A Centennial Exhibition Here and Now: The Vision of the Jewish Labor Bund in Interwar Poland Program Editor Finance Committee Nelly Furman Adi Diner and Abe Goldwasser -

Jews, Poles, and Slovaks: a Story of Encounters, 1944-48

JEWS, POLES, AND SLOVAKS: A STORY OF ENCOUNTERS, 1944-48 by Anna Cichopek-Gajraj A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Todd M. Endelman, Co-Chair Associate Professor Brian A. Porter-Sz űcs, Co-Chair Professor Zvi Y. Gitelman Professor Piotr J. Wróbel, University of Toronto This dissertation is dedicated to my parents and Ari ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am greatly appreciative of the help and encouragement I have received during the last seven years at the University of Michigan. I have been fortunate to learn from the best scholars in the field. Particular gratitude goes to my supervisors Todd M. Endelman and Brian A. Porter-Sz űcs without whom this dissertation could not have been written. I am also thankful to my advisor Zvi Y. Gitelman who encouraged me to apply to the University of Michigan graduate program in the first place and who supported me in my scholarly endeavors ever since. I am also grateful to Piotr J. Wróbel from the University of Toronto for his invaluable revisions and suggestions. Special thanks go to the Department of History, the Frankel Center for Judaic Studies, and the Center of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Michigan. Without their financial support, I would not have been able to complete the program. I also want to thank the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture in New York, the Ronald and Eileen Weiser Foundation in Ann Arbor, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, and the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC for their grants. -

![Program Here [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5164/program-here-pdf-3395164.webp)

Program Here [Pdf]

Organizers: The event is organized within the framework of the Global Education Outreach Program. GEOP INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH WORKSHOP Building Culture and Community: The program is made possible thanks to the support to Taube Philanthropies, the William K. Bowes, Jr. Foundation, and the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland. Jewish Architecture and Urbanism in Poland 29-31 May 2019, POLIN Museum POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews 6 Anielewicza St. 00-157 Warsaw [email protected] www.polin.pl/en On the cover: View of the Luxembourg Gallery and the Grand Hotel in Warsaw – Postcard/ POLIN Museum. DAY 1, 29 MAY / CONFERENCE ROOM A 3:00-4:00 Session III: Case Studies of Jewish Builders and Buildings 5:30-6:00 Registration and informal greetings Chair: Ruth Leiserowitz, German Historical Institute Barbara Zbroja, National Archives, Krakow – They Also Built Krakow: The Role 6:00-7:30 Keynote lecture by Rudolf Klein, Szent István University, of Jewish Architects Budapest – Metropolitan Jewish Cemeteries in Central and Eastern Europe Cecile Kuznitz, Bard College – Jewish Architecture as an Expression of Doikeyt [“Hereness”]: Examples from Vilna and Lublin 7:30 Dinner 4:00-4:30 Coffee break DAY 2, 30 MAY / CONFERENCE ROOM B 4:30-6:00 Session IV: Perceptions and Roles of Urban Space 10:00-10:30 Opening Remarks Chair: Renata Piątkowska, POLIN Museum 10:30-12:00 Session I: Spaces of Religious and Communal Life Mikhail Krutikov, University of Michigan – Polish and Jewish Urban Space Chair: Eleanora Bergman, Emanuel -

Annual Report

Annual Report CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Table of Contents A Message from Bruce Slovin, Chairman of the Board 2 Our Mission 3 The Center Facility Education, Exhibition and Enlightenment 5 American Jewish Historical Society 10 American Sephardi Federation 12 Leo Baeck Institute 14 Yeshiva University Museum 16 YIVO Institute for Jewish Research 18 Center Affiliates 20 Exhibitions 21 Program Highlights 22 Philanthropic Giving at the Center for Jewish History 24 Benefactors 25 Center Volunteers and Docents 28 Financial Report Insert Governance Insert Michael Luppino 1 CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY From the Chairman August, 2005 he nurturing that every child experiences during the first five Boris and Bessie Thomashefsky. years of its life is vital in determining that child’s character and The Leo Baeck Institute’s commemorations of its 50th year Tfuture. These vital years, marked by amazingly rapid change was a particularly poignant reminder of the miracle of Jewish survival, and inspiring growth, chart the transition from infancy to responsibili- since none of its founders whose visionary goal was to ensure the sur- ty, and culminate in the child’s entry into formal schooling and social vival of the material documentation of the remnants of German Jewry interaction with his or her peers. in the period immediately following the years of Nazi terror, could have As I look back on the past five, formative years of the Center for imagined that this Institute would be thriving into the 21st century. Jewish History–the American Jewish community’s youngest and Yeshiva University Museum, in collaboration with Yeshiva’s already richest and most important institution for the study of our Cardozo Law School and Bernard Revel Graduate school, simultane- people’s history–I find myself experiencing emotions analogous to ously commemorated two other major milestones in Jewish spiritual the naches of a parent seeing his child off for the first day of school. -

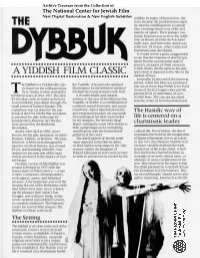

Read NCJF Program Notes

Archive Treasure from the Collection of The National Center for Jewish Film New Digital Restoration & New English Subtitles of Jewish communities in the large Sender brings Leah to Miropole to himself by reciting the Kaddish for the cities and urban centers of Eastern seek the help ofReb Azriel. His heart tormented soul. And yet, the Messen Europe, and eventually America, was rending confession of disregard for the ger cautions the Rebbe that although to a great extent an outgrowth of shtetl vow made eighteen years earlier the vow has been declared not binding !ife, institutions, and values. prompts the Rebbe to appeal to the and has been set aside, with Sender deceased Nisn to forgive Sender, and repentant and Leah's life saved, the The Story declare the vow null and void, since, heavens stilJ demand justice: the fulfill •••••••••••••••••••••• according to law, an agreement per ment of the vow for the lovers' sake, Sender and Nisn, former yeshiva stu taining to a thing not yet born is not for their hopes and spiritual struggle dents and now devoted friends, have binding. In an elaborately orchestrated for happiness together. Ultimately, come from afar to celebrate the High ritual, theRebbe succeeds finally in both worlds converge on the vow Holy Days with their spiritual leader, exorcising the dybbuk. TheRebbe's made between Nisn and Sender, for Reb Azriel, the HasidicRebbe of Miro earthly justice notwithstanding, the with the vow fulfilled, a human pole. In their desire to strengthen the young lovers are ultimately reunited in beings moral responsibility for one's bonds of friendship, Sender and Nisn death and, as the mysterious Messen fellow human being is reaffirmed. -

Gazeta Summer 2015

Photo: Jason Francisco Photo: Jason Francisco Volume 22, No. 2 Gazeta Summer 2015 A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Vera Hannush, Alice Lawrence, Aleksandra Makuch, LaserCom Design. Front and Back Cover Photos: Jason Francisco TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 1 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 2 HISTORY & CULTURE Jewish Heritage in Lviv Today–A Brief Survey By Jason Francisco ............................................................................................................. 3 Discovering the History of a Lost World By Dr. Tomasz Cebulski ....................................................................................................... 6 EDUCATION My Mi Dor Le Dor Experience By Klaudia Siczek ................................................................................................................ 9 Hillel Professionals Explore Poland’s Jewish Revival, Contemplate Student Encounters By Lisa Kassow ................................................................................................................. 12 New Notions of “Polonia”: Polish- and Jewish-American Students Dialogue with Polish Foreign Ministry on Taube Study Tour ........................................................ 15 -

Yedies 189 Winter 99

hshgu, hshgu, No. 189 IVOIVO Winter 1999 YYNEWS hHuu† pui Alter Kacyzne’s Photographs YIVO Celebrates Publication of Historic Album IVO began its 75th Anniversary year with a Ycelebration for Poyln — Jewish Life in the Old YIVO Institute Country, a new book of pre-Holocaust photo- for graphs taken throughout Poland by the renowned Yiddish author and photographer Alter Kacyzne. Jewish (A selection of photographs from the book appears Research on pages 18 – 21.) Edited by YIVO Chief Archivist hHshagr Marek Web and published by YIVO in cooperation uuhxbaTpykgfgr with Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt, Poyln has thbxyhyuy ≈ thbxyhyuy received excellent reviews from the Forward, the Atlanta Jewish Times and the Canadian Jewish News hHuu† and has been named a Book-of-the-Month selection. Its initial printing in English is 17,000 copies. Marek Web, Chief Archivist and editor of Poyln, with YIVO “A simultaneous German edition of Poyln was Board member and author Fanya Gottesfeld Heller. released just in time for the Frankfurt Book Fair,” Kacyzne had a remarkable sensibility for his Board Chairman Bruce Slovin told the 100 people subjects, whether in studio portraits, on a Warsaw who attended the November 4th reception and street, or in a shtetl marketplace. He was known to book signing in the Center for Jewish History have been unusually painstaking in his work, library. “Marek Web has done Herculean labor in never satisfied until he had achieved exactly the bringing this book to publication.” right effect. This new book provides a window “We are very proud to be here today,” Dr. Carl into the lost world of Polish Jewry through the Rheins, YIVO Executive Director, commented. -

MIKHAIL KRUTIKOV May 18, 2016 Department of Slavic Languages

MIKHAIL KRUTIKOV May 18, 2016 Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and The Frankel Center for Judaic Studies, University of Michigan Office: Home: MLB 3040 572 Glendale Cir. 812 E. Washington St Ann Arbor, MI 48103 Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1275 Cell 734-709-6979 Office 734-764-5355 [email protected] EMPLOYMENT 2015- Chair, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Michigan 2014 - Professor of Slavic and Judaic Studies, University of Michigan 2010 - 2014 Associate Professor of Slavic and Judaic Studies, University of Michigan, 2004 - 2010 Assistant Professor of Slavic and Judaic Studies, University of Michigan, 2002-2003 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Michigan 1999-2002 Lecturer in Yiddish Literature, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1996-2001 Lecturer in Yiddish Literature, Oxford Institute for Yiddish Studies, Oxford 1995-1996 Academic Curator, Project Judaica, Joint academic program between the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and Russian State University for Humanities OTHER ACADEMIC AFFILIATIONS 2000- Fellow, European Humanities Research Centre, Oxford University 2001- Senior Research Associate, Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies EDUCATION Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Ph.D. in Jewish Literature, 1998 A. M. Gorky Institute of Literature, Moscow, Editor Certificate in Yiddish language and literature, 1991 Moscow State University, Diploma (B.Sc. equivalent), Mathematics, 1979 Krutikov CV 2015 2 FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS 2014-15 Head Fellow, Theme Year Jews and Empire, Frankel Institute for Advanced Judaic Studies 2012 Modern Language Association Fenia and Yaakov Leviant Memorial Prize in Yiddish Studies for 2008-2011 2009 Guest Scholarship, Project Charlottengrad and Scheunenviertel: East-European Jewish Migrants in Weimar Berlin during the 1920s-30s.