The Story of YIVO's Polish Jewish Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, launch May 1 with an event at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York completion of this landmark project in December 2021. Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed rare or unique books have now been digitized and put Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah online for researchers, teachers, and students around the photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article world to read. The next important step in developing (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to European Jewish Life. The museum will launch early explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures 2021. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, is currently being tested. Through Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us the art of storytelling the museum will provide the online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). historical context for the archive’s vast array of original documents, books, and other artifacts, with some materials being translated to English for the first time. -

UNIT FOUR: Songs of Belonging

UNITUNIT 4 FOUR:Studen t Workbook Songs of Belonging: Jewish/Israeli Songs Student Workbook A curriculum for Israel Engag ement Written by Belrose Maram In collaboration with Gila Ansell Brauner Elisheva Kupferman, Chief Editor Esti-Moskovitz-Kalman, Director of Education 1 UNIT 4 Student Workbook Lesson 1: Classical Poems and Songs Introduction In the first unit we explored the different types of connections that the Jewish People have with Israel. Since the Jews were expelled from the Land of Israel in ancient times, they have endeavored to remember and connect to the land in a variety of ways. The Arts in particular have played a major role in the expression of connection to Israel. It has provided an avenue for expression of yearning for the land, through poems, visual arts, music, etc. Even today, while we have the Modern State of Israel, artists worldwide are still expressing their connection to Israel through art. In the first lesson of this unit, we will learn about 2 poems that were written before the creation of the Modern State of Israel. One is a Psalm from the Bible: “If I forget you, O Jerusalem” and the second is a poem from the medieval period written by Yehuda Halevi: " My Heart is in the East, and I am in the furthermost West ". After analyzing both, we will do a short assignment asking you to reflect on Hatikva , the Israeli Hymn which later became Israel’s National Anthem, applying the themes of yearning you have studied in class to the hymn. " אם אשכך ירושלים ,If I forget you, O, Jerusalem " .1 The poem, If I forget you, O, Jerusalem , is part of Tehillim, Psalm #137, which is attributed to the First Exile, in Babylon, in the 6 th century B.C.E. -

2016 Pakn Treger Translation Issue

Table of Contents “You Have Not Betrayed Me Since the Day We Met” and “You Olive Tree in the Night” by Avrom Sutzkver, translated by Maia Evrona “On the Landing” by Yenta Mash, translated by Ellen Cassedy “From Eternity to Eternity: Thoughts and Considerations in Honor of Passover” by Moyshe Shtarkman, translated by Ross Perlin “In Which I Hate It and Can’t Stand It and Don’t Want to and Have No Patience at All” by Der Tunkeler, translated by Ri J. Turner “Letters” by H.D. Nomberg, translated by Daniel Kennedy “Blind Folye” by Froyim Kaganovski, translated by Beverly Bracha Weingrod “Mr. Friedkin and Shoshana: Wandering Souls on the Lower East Side” (an excerpt from Hibru) by Joseph Opatoshu, translated by Shulamith Z. Berger “Coney Island, Part Three” by Victor Packer, translated by Henry Sapoznik “Old Town” (an excerpt from The Strong and the Weak) by Alter Kacyzne, translated by Mandy Cohen and Michael Casper An Excerpt from “Once Upon a Time, Vilna” by Abraham Karpinowitz, translated by Helen Mintz “To a Fellow Writer” and “Shloyme Mikhoels” by Rachel H. Korn, translated by Seymour Levitan “The Destiny of a Poem” by Itzik Manger, translated by Murray Citron “The Blind Man” by Itsik Kipnis, translated by Joshua Snider Introduction he translation theorist Lawrence Venuti closes his short essay “How to Read a Translation” on a note of defiance: T Don’t take one translation of a foreign literature to be representative of the language, he tells us. Compare the translation to other translations from the same language. Venuti’s point is both political and moral. -

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

CURRICULUM VITA Anita Norich

CURRICULUM VITA Anita Norich ([email protected]) Department of English Language and Literature Frankel Center for Judaic Studies University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 EDUCATION 1979 Ph.D. in English literature, Columbia University. Dissertation: “Benjamin Disraeli’s Novels: Personal and Historical Myths” 1975-79 Fellow in Yiddish literature, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research 1976 M.Phil., English literature, Columbia University—with High Honors 1974 M.A., English literature, Columbia University—with Distinction. “George Eliot and the Jews: Contemporary Responses to Daniel Deronda” 1973 A.B., Barnard College—Magna cum laude PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2007- Professor of English and Judaic Studies, University of Michigan 2006-2008 Frankel Institute for Judaic Studies Executive Director, Univ. of Michigan 1. Interim Associate Chair, Department of English, University of Michigan 1998-99 Interim Director, Frankel Center for Judaic Studies, University of Michigan 1991- Associate Professor of English and Judaic Studies, University of Michigan 1991-94 Chair of Undergraduate Studies, Department of English, University of Michigan 1983-1991 Assistant Professor, Department of English and Judaic Studies Program, University of Michigan p. 1 1981-83 Lady Davis Postdoctoral Fellow in Yiddish, Hebrew University, Jerusalem 1980-81 Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania, Program in Comparative Literature 1979-81 Adjunct Assistant Professor, New York University, School of Continuing Education; Assistant Program Coordinator, General -

Profile ‘It’S About Something Much Bigger Than You!’

PROFILE ‘IT’S ABOUT SOMETHING MUCH BIGGER THAN YOU!’ EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW BY BORUCH MERKUR WRITTEN BY CHANA KATZ Friday afternoon. Music superstar enters and immediately starts to sing moving in their seats, if you can Matisyahu is being trailed by a a melody, “Dum, dum, dum, dum, imagine. The audience is ignited. reporter from one of America’s most dah, dah...” and then vocalizes a Matisyahu finishes, gives a shy prominent newspapers, The series of sounds that sizzle and but appreciative smile and is ushered Washington Post. Erev Shabbos and explode into song. into the interview seat. Taking in his the reporter is barely keeping pace The cameras occasionally flash on Chasidic composure, the host asks with the Chassid as he navigates the the crowd in the audience and no one with great interest, “How did you streets of New York City. is sitting still. Everyone is literally become this rapper?! The article is published with the Matisyahu smiles and says, headline, “Funny, He Doesn’t Look “Basically, I wasn’t always religious. I Jamaican!” referring to the reggae A SIGN THAT GEULA IS NEAR! was raised in a non-Orthodox Jewish roots of his music. Still, the essence family and listened to reggae like any “The success of Matisyahu is of the story is G-dliness. “Matisyahu high school kid.” does this (gives up Shabbos nothing short of pure G-dliness performances, etc.) because, as he and certainly the work of the Host: “You get criticism from the sees it, he has what he had because Rebbe MH”M. -

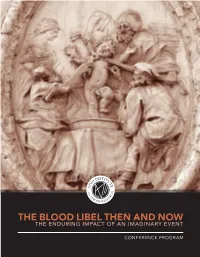

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

September / October

AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR YAD VASHEM Vol. 46-No. 1 ISSN 0892-1571 September/October 2019-Tishri/Cheshvan 5780 “TWO ARE BETTER THAN ONE… AND A THREEFOLD CORD CANNOT QUICKLY BE BROKEN” n Sunday, November 17, 2019, the are leaders of numerous organizations, including membrance for their grandparents, and to rein- American Society for Yad Vashem AIPAC, WIZO, UJA, and American Friends of force their commitment to Yad Vashem so that will be honoring three generations of Rambam Hospital. the world will never forget. Oone family at our Annual Tribute Din- Jonathan and Sam Friedman have been ll three generations, including ner in New York City. The Gora-Sterling-Fried- deeply influenced by Mona, David and their ex- David’s three children — Ian and his man family reflects the theme of this year’s traordinary grandparents, Jack and Paula. Grow- wife Laura, Jeremy and his wife Tribute Dinner, which comes from Kohelet. “Two ing up, they both heard Jack tell his story of AMorgan, and Melissa — live in the are better than one… and a threefold cord can- survival and resilience at the Yom HaShoah pro- greater New York City area. They gather often, not quickly be broken” (4:9-12). All three gener- ations are proud supporters of Yad Vashem and are deeply committed to the mission of Holo- caust remembrance and education. Paula and Jack Gora will receive the ASYV Remembrance Award, Mona and David Sterling will receive the ASYV Achievement Award, and Samantha and Jonathan Friedman and Paz and Sam Friedman will receive the ASYV Young Leadership Award. -

JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English

MONDAY The Rise of Yiddish Scholarship JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English As Jewish activists sought to build a modern, secular culture in the late nineteenth century they stressed the need to conduct research in and about Yiddish, the traditionally denigrated vernacular of European Jewry. By documenting and developing Yiddish and its culture, they hoped to win respect for the language and rights for its speakers as a national minority group. The Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute], known by its acronym YIVO, was founded in 1925 as the first organization dedicated to Yiddish scholarship. Throughout its history, YIVO balanced its mission both to pursue academic research and to respond to the needs of the folk, the masses of ordinary Yiddish- speaking Jews. This talk will explore the origins of Yiddish scholarship and why YIVO’s work was seen as crucial to constructing a modern Jewish identity in the Diaspora. Cecile Kuznitz is Associate Professor of Jewish history and Director of Jewish Studies at Bard College. She received her Ph.D. in modern Jewish history from Stanford University and previously taught at Georgetown University. She has held fellowships at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In summer 2013 she was a Visiting Scholar at Vilnius University. She is the author of several articles on the history of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Jewish community of Vilna, and the field of Yiddish Studies. English-Language Bibliography of Recent Works on Yiddish Studies CECILE KUZNITZ Baker, Zachary M. -

American Yiddish Poetry Video Conference

YIDDISH BOOK CENTER 2018 Great Jewish Books Book Club Video Conference American Yiddish Poetry by Benjamin and Barbara Harshav with Barbara Harshav August 29, 2018 8:00 p.m. EDT C.A.R.T. CAPTIONING SERVICES PROVIDED BY: www.CaptionFamily.com Edited by Jessica Parker * * * * * Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) is provided in order to facilitate communication accessibility and may not be a totally verbatim record of the proceedings. * * * * * JESSICA PARKER: Okay, we're going to get started. Hi, everyone, and welcome to our third video conference of the 2018 Book Club. Thank you for your careful reading, your thoughtful comments, and your insightful perceptions in our Facebook group and via e-mail. I'm so glad that you're all joining us this evening. I'm Jessica Parker, the coordinator for the Great Jewish Books Book Club. In just a moment, I'm going to introduce our featured guest, "American Yiddish Poetry" editor and translator, Barbara Harshav. But first, I want to tell you about the structure for this evening. All participants will be muted to prevent excessive background noise. Barbara will start with a 15-minute introduction, and then we'll open it up to questions for about 45 minutes. You can ask them questions by typing in the chat box. You can ask her questions, sorry, by typing in the chat box. To access the chat box, hover over the bottom of your Zoom window. You should see a speech bubble with "chat" written underneath it. Click on that speech bubble to open the chat window. You'll be able to send messages privately to individuals, or to everyone. -

Introduction Vered Karti Shemtov and Anat Weisman

Form: Introduction Vered Karti Shemtov and Anat Weisman An issue dedicated to Benjamin Harshav (Vilnius, 1928–New Haven, 2015) Everything is form and life itself is a form Honoré de Balzac Meter weaves a parallel thread underneath—and throughout—the verbal fabric Benjamin Harshav Form remains a word in common critical currency. It is, it seems, one that we cannot do without. After all, what other word could describe, with so little fuss, but also with due sense of estrangement and embodiment, the object in question: the art form in all its integral complexity? What other word could be so wittily and succinctly resonant, drawing into its small scope such a crowd of possibilities? Angela Leighton he word “form” itself, as Angela Leighton shows us in her book On Form: Poetry, Aestheticism and the Legacy of a Word, has a slippery meaning, one that changed from Plato to today. Although a necessary word for literary studies, it seems “self-sufficient Tand self-defining, is restless, tendentious, a noun lying in wait for an object.”1 What do we talk about when we talk about form in literary studies today, one hundred years after the establish- ment of the Russian Formalist circles?2 What are the objects that we have in mind? And can these objects be seen and studied as separated from other contexts? 1 Angela Leighton, On Form: Poetry, Aestheticism and the Legacy of a Word (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 1. 2 If we see the beginning of the movement as the 1916 establishment of the Society for the Study of Poetic Language (OPOYAZ) in Saint Petersburg (then Petrograd) by Boris Eichenbaum, Viktor Shklovsky, and Yury Tynyanov, and a bit over a century since the 1914 Moscow Linguistic Circle was founded by Roman Jakobson. -

Touching the Memory

Touching the Memory By William Eaton Zeteo is Reading, September 2014 My father usually invited an oirech (a poor person) from among those who had lined up at the door of the Beit HaMidrash to join us for [a Sabbath] meal. These were itinerant beggars, of whom there were, unfortunately, many in Poland. I was fascinated by these vagabonds who lived at the margin of our society, and their presence at our table added excitement and mystery to the celebration. This from a memoir by the former rabbi and director of Harvard-Radcliffe Hillel, Ben-Zion Gold. In the Introduction, Gold says that he wrote this memoir, The Life of Jews in Poland before the Holocaust, to rectify an “imbalance in the way we remember the Jews of Europe.” That is, we focus on the Holocaust and ignore how Jews lived, the “vitality and richness of Jewish life” in Europe before the most deadly wave of anti-Semitism—and of mass murder of people of many backgrounds. (See, please, Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, and I would also here recommend Tzvetan Todorov’s La Conquête de l’Amérique: La question de l’autre — The Conquest of America: The Question of the Other — which speaks powerfully of human savagery on our side of the Atlantic.) That said, I must also note that Gold’s memoir came most to life for me in its antepenultimate chapter, which tells how he, unlike his parents and three sisters, escaped: avoided being murdered by the Germans. Reading this chapter I was reminded of how my William Eaton is the Editor of Zeteo.