Exploring the Creative Mindset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing Type, a History from Jung to Today

Developing Type: A history from Jung to today Type measurement methods used today are based on the work of C.G.Jung, who commenced developing his theory of psychological types a century ago. He commenced with extraversion–introversion, and over time added the mental activities or functions of sensation, intuition, thinking and feeling. None of these terms were original; Jung provided his own definitions and distinctions.People responded to Jungʼs ideas from the very start, before the introduction of functions, and placed their own perspective on his work. This presentation takes a broad but in depth brush to the history of various interpretations and methods associated with Jungʼs typology up to the present day, commencing with Jungʼs construction and early use of his type categories, a period of two to three decades. It includes interpretations and explanations of his work by others, whether in general texts and seminars in disparate fields including society, medicine and art. Measurement (Gray and Wheelwright; Isabel Myers and Katharine Briggs) as a particular cultural and methodological approach to Jungʼs typology will also be examined. This will include the development a particular language of type from measurement results and associated texts, but also the products and orientation of instrument use and the drift to the use of the term personality type. Influences from within and without the Jungian field will also be discussed, notably David Keirseyʼs temperaments (associated with Isabel Myers, but not Jung) and John Beebeʼs archetypal approach. It is intended as a brief contribution to the current challenges to the plausibility of type dynamics and development. -

Extending the Abstraction of Personality Types Based on MBTI with Machine Learning & Natural Language Processing

Extending the Abstraction of Personality Types based on MBTI with Machine Learning & Natural Language Processing (NLP) Carlos Basto Abstract This study focuses on the essential basis for the classification of psychological types – that is, the basis This paper presents a data-centric approach with for determining a broader spectrum of characteristics Natural Language Processing (NLP) to predict derived from a human being (Jung and Baynes, 1953)– personality types based on the MBTI (an through the use of machine learning and natural language introspective self-assessment questionnaire that processing. This topic is crucial in differential indicates different psychological preferences psychology and has been extensively worked on by Carl Jung (further details and correlated studies available no about how people perceive the world and make 1 decisions) through systematic enrichment of IAAP ) which allows us to ensure that the psychological text representation, based on the domain of the classification of different types of individuals is a area, under the generation of features based on promising step towards self-knowledge. three types of analysis: sentimental, grammatical and aspects. The experimentation Under Jung's proposal (Geyer, 2014), a dominant had a robust baseline of stacked models, with function, along with the dominant attitude, characterizes premature optimization of hyperparameters consciousness, while its opposite is repressed and through grid search, with gradual feedback, for characterizes the unconscious. This dualism is extremely each of the four classifiers (dichotomies) of valuable in understanding and, eventually, predicting MBTI. The results showed that attention to the personality types. Thus, this classification opened doors data iteration loop focused on quality, for further enrichment of his work. -

O Processo Decisório Judicial À Luz Dos Tipos Psicológicos De Carl Gustav Jung

O PROCESSO DECISÓRIO JUDICIAL À LUZ DOS TIPOS PSICOLÓGICOS DE CARL GUSTAV JUNG (DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO ) ORIENTADORA: PROF A DRA LÍDIA REIS DE ALMEIDA PRADO CANDIDATO: ANTOIN ABOU KHALIL (N O USP: 492.351) FACULDADE DE DIREITO DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOSOFIA E TEORIA GERAL DO DIREITO (DFD) SÃO PAULO (SP) 2010 Todas as opiniões que há sobre a natureza Nunca fizeram crescer uma erva ou nascer uma flor. Toda a sabedoria a respeito das cousas Nunca foi cousa em que pudesse pegar, como nas cousas; Se a ciência quer ser verdadeira, Que ciência mais verdadeira que a das cousas sem ciência? Fecho os olhos e a terra dura sobre que me deito Tem uma realidade tão real que até as minhas costas a sentem, Não preciso de raciocínio onde tenho espáduas. --- x --- Assim como falham as palavras quando querem exprimir qualquer pensamento, Assim falham os pensamentos quando querem exprimir qualquer realidade. Mas, como a realidade pensada não é a dita mas a pensada, Assim a mesma dita realidade existe, não o ser pensada. Assim tudo o que existe, simplesmente existe. O resto é uma espécie de sono que temos, Uma velhice que nos acompanha desde a infância da doença. --- x --- O espelho reflete certo; não erra porque não pensa. Pensar é essencialmente errar. Errar é essencialmente estar cego e surdo. (Alberto Caeiro) 1 1 PESSOA, Fernando. Obra e Poética em Prosa, vol. 1, in “Poemas Inconjuntos”, Lello & Irmão – Editores, Porto, 1986, pp. 798, 792 e 793. 1 RESUMO O presente trabalho tem por objeto a análise da influência do psiquismo do juiz no modo como preside o processo – estilo de colheita de dados e relacionamento com os de- mais sujeitos (partes e advogados, principalmente) – e produz suas decisões. -

A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES and FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION in UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS Frank Capellan Southeastern University - Lakeland

Southeastern University FireScholars College of Education Fall 2017 A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION IN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS Frank Capellan Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: https://firescholars.seu.edu/coe Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, First and Second Language Acquisition Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Capellan, Frank, "A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION IN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS" (2017). College of Education. 11. https://firescholars.seu.edu/coe/11 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Education by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION IN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS By FRANK CAPELLAN A doctoral dissertation submitted to the College of Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Curriculum and Instruction Southeastern University October, 2017 DEDICATION For Otilia, with everlasting love iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Over the course of my doctoral journey, I have received support and encouragement from a great number of people. I cannot fully express in words my gratitude and indebtedness to all of you for encouraging me on this long, and exhausted journey. I am deeply grateful for my dissertation committee, Dr. Joyce Tardáguila Harth, Dr. Jim Anderson, and Dr. Patricia Coronado Domenge for their incredible guidance, encouragement, and accountability throughout my research, and writing. Your counsel throughout the study process exemplified the spirit of the learning journey. -

70 Years of the MBTI® Assessment

70 years of the MBTI® assessment The MBTI® tool has a long and prestigious history, all of which lead to its huge success as the world’s most widely used and recognised personality tool. Katharine Briggs and Isabel Myers: the creators The MBTI questionnaire, first published in 1943, was originally developed in the United States by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers. Katharine Briggs was inspired to start researching personality type theory when she first met Isabel’s future husband, Clarence Myers. Whilst Clarence was a very eligible match for her daughter, Katharine noticed that he had a different way of seeing the world to her and her family, and was intrigued enough to start an extensive literature review based on understanding different temperaments. It was shortly after Carl Jung’s publication of Psychological Types (1921; 1923 in English) that Katharine realised how closely his theories resembled hers, and how much more developed they were. Inspiration from Carl Jung Carl Jung was a renowned Swiss psychiatrist, and is still seen by many, along with Sigmund Freud, as one of the founding fathers of modern-day psychology. His theory of psychological types proposes that people are innately different, both in terms of the way they see the world and take in information, and how they make decisions. Briggs and Myers thought that these ideas were so useful that they wanted to make them accessible to a wider audience. TranslatingTranslating the the theory theory into into a practical a practical tool tool Driven by a desire to help people understand themselves and each other better in a post-war climate, Isabel Myers set about devising a questionnaire that would identify which psychological type a person was. -

Thesis and Dissertation Guidelines

Temperament Types, Job Satisfaction, Job Roles, and Years of Service of Doctor of Educational Leadership Candidates and Graduates Pamela B. Turner B.S., Mid America Nazarene University, 1972 M.A., University Missouri-Kansas City, 1984 Submitted to the Graduate Department and Faculty of the School of Education of Baker University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership February 3, 2015 Copyright 2015 by Pamela B. Turner Dissertation Committee Major Advisor ii Abstract Some organizational studies examining the relationship between job satisfaction, and temperament type have indicated marginal to significant correlations between the two variables (Herzberg, Mausner, and Snyderman., 2000; Keirsey, 1998; Spector, 1997. Other studies examining the relationship between job satisfaction, temperament type, job roles, and years of service have produced mixed results (Jennings, 1999). One purpose of this survey study was to examine the extent to which there is a relationship between job satisfaction and temperament of doctoral candidates and graduates. A second purpose for this survey study was to examine the extent to which there is a relationship between job satisfaction and job role. The third purpose for this survey study was to examine the extent to which the relationship between job satisfaction and job role is affected by temperament. The fourth purpose of this survey study was to examine the relationship between job satisfaction and years of service. The fifth purpose for this survey study was to examine the extent to which the relationship between job satisfaction and years of service is affected by temperament. The methodology involved a purposeful sampling of 45 doctoral candidates and graduates enrolled in cohorts 1-9 at a small, private liberal arts university in the Midwest. -

Is Myers-Briggs up to the Job? Murad Ahmed

February 11, 2016 10:26 am Is Myers-Briggs up to the job? Murad Ahmed Share Author alerts Print Clip Comments While the personality test devised in the 1960s remains popular, can it still claim to be relevant? ©Spencer Wilson On the first day of his new job at the management consultants McKinsey & Company, Alick Varma, then 22, was asked to take a test. The questionnaire quizzed him on aspects of his personality, asking, for instance, whether he would “rather be considered a practical person or an ingenious person?” and whether he considered himself “a ‘good mixer’ or rather quiet and reserved?” Varma, who joined McKinsey as a business analyst in October 2007, was taking the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) — a personality test that has become a rite of passage for millions of white- collar workers. Since the 1960s, when the test began to be rolled out across corporate America, more than 50 million people around the world are estimated to have taken it. Myers-Briggs has a particularly strong influence at McKinsey, according to current and former staffers (when contacted for this article, McKinsey said it does not comment on its “internal processes”.) Included in the basic biographical information supplied on the company’s staff profile pages are addresses, educational background — and MBTI personality types. When a team begins a new project, associates often start by discussing their respective personality traits — are you an “E” (extrovert) or an “I” (introvert)? ©Spencer Wilson As Varma settled into his new job at the company, working long hours alongside other ambitious overachievers, he found the insights provided by the test helpful. -

Evaluating the Validity of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Theory

DOI: 10.1111/spc3.12434 ARTICLE Evaluating the validity of Myers‐Briggs Type Indicator theory: A teaching tool and window into intuitive psychology Randy Stein1 | Alexander B. Swan2 1 Cal Poly Pomona Abstract 2 Eureka College Despite its immense popularity and impressive longevity, Correspondence Randy Stein, College of Business the Myers‐Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) has existed in a Administration, Cal Poly Pomona, 3801 W parallel universe to social and personality psychology. Here, Temple Ave, Pomona, CA 91768. Email: [email protected] we seek to increase academic awareness of this incredibly popular idea and provide a novel teaching reference for its conceptual flaws. We focus on examining the validity of the Jungian‐based theory behind MBTI that specifies that people have a “true type” delineated across four dichotomies. We find that the MBTI theory falters on rigorous theoretical criteria in that it lacks agreement with known facts and data, lacks testability, and possesses internal contradictions. We further discuss what MBTI's continued popularity says about how the general public might evaluate scientific theories. 1 | INTRODUCTION Presumably, a purpose of the field of psychology is to assist the general public in becoming psychologically literate. Unfortunately, the ideas about psychology that gain the most traction with the public can lack theoretical rigor. Arguably, the most popular psychology idea in the world is the Myers‐Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Seven decades after its inception, the administration and interpretation of the MBTI is a huge business and force in shaping the general public's perceptions of psychology, championed by the MBTI's current owners, The Myers‐Briggs Company (formerly known until late 2018 as CPP). -

O Processo Decisório Judicial À Luz Dos Tipos Psicológicos De Carl Gustav Jung

O PROCESSO DECISÓRIO JUDICIAL À LUZ DOS TIPOS PSICOLÓGICOS DE CARL GUSTAV JUNG (DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO ) ORIENTADORA: PROF A DRA LÍDIA REIS DE ALMEIDA PRADO CANDIDATO: ANTOIN ABOU KHALIL (N O USP: 492.351) FACULDADE DE DIREITO DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOSOFIA E TEORIA GERAL DO DIREITO (DFD) SÃO PAULO (SP) 2010 RESUMO O presente trabalho tem por objeto a análise da influência do psiquismo do juiz no modo como preside o processo – estilo de colheita de dados e relacionamento com os de- mais sujeitos (partes e advogados, principalmente) – e produz suas decisões. Há, portanto, uma interface entre Direito e Psicologia, tomando-se como paradigma a teoria dos tipos psicológicos de Carl Gustav Jung e seguidores, com os acréscimos que lhe foram feitos por Isabel Briggs Myers e Katharine Cook Briggs. Para fins de contraste, a teoria de Jung é confrontada com a tipologia psicanalítica de Freud. No âmbito jurídico, especial atenção é dada à relação das funções pensamento e sentimento com o “senso de justiça”, sugerindo- se que a teoria tridimensional do Direito, de Miguel Reale, seja a expressão jurídica do uso equilibrado das funções perceptivas e judicativas. Esta a primeira parte do trabalho. Na segunda, são analisados tipologicamente seis magistrados do Tribunal de Justiça do Estado de São Paulo, tomando-se por base sua atuação profissional, conforme por eles expressa em entrevista. A entrevista foi feita a partir de um questionário padrão, de modo a estabelecer paralelos discursivos e daí colher semelhanças e diferenças, analisadas à luz do tipo psicológico aferido. Para aferição do tipo psicológico de cada entrevistado, além da análise do conteúdo de sua fala, foi aplicado um segundo questionário, de natureza especí- fica. -

Theory and Research Article Collection from the Bulletin of Psychological Type.Pdf

TYPE ARCHIVE WWW.PETERGEYER.COM.AU PETER GEYER Research and Theory A collection of articles published in the APTi Bulletin of Psychological Type as Interest Area Coordinator for Research and Theory 2006–2010 1. Research and Theory, From Inside and Outside It's an honour to be asked to undertake the role of APTi Interest Area Coordinator for Research and Theory, which really starts off with this article. What follows are some of my current thoughts The MBTI, as a practical implementation of C.G.Jung's theory of psychological types, requires close attention to both research/theory and practice in order to work effectively. Sometimes this means attention to what aspect of theory works, what doesn't, and why. An old saw states "there's nothing so practical as a good theory." Isabel Myers once reflected on the natural tendency for intuitives to change aspects of her ideas and practice. This was naturally a good thing, but sometimes she wished that inquiry was made into why she did what she did, before changing things. This is a fundamental principle of research anywhere and involves investigation of present and past. Sometimes we have to separate research and theory from practice in order to work out what the implications are of the theory or research results and its consistencies or otherwise of other ideas. MBTI and type–related conferences may therefore make an unintentional mistake if they require their presenters to provide practical hints in their presentations. I've seen this requirement regarding some recent events in various countries, Often the knowledge presented by a researcher or theoretician is practical in itself in terms of developing personal understanding; other times it can require a person other than the presenter of a well-developed idea or piece of theory to apply the learning. -

Jungian Character Network in Growing Other Character Archetypes in Films 13

Youngsue Han : Jungian Character Network in Growing Other Character Archetypes in Films 13 https://doi.org/10.5392/IJoC.2019.15.2.013 Jungian Character Network in Growing Other Character Archetypes in Films Youngsue Han German Interpretation and Translation Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Yongin-si, 17035, Republic of Korea ABSTRACT This research demonstrates a clear visual outline of character influence-relations in creating Jungian character archetypes in films using R computational technology. It contributes to the integration of Jungian analytical psychology into film studies by revealing character network relations in film. This paper handles character archetypes and their influence on developing other character archetypes in films in regards to network analysis drawn from Lynn Schmidt’s analysis of 45 master characters in films. Additionally, this paper conducts a character network analysis visualization experiment using R open-source software to create an easily reproducible tutorial for scholars in humanities. This research is a pioneering work that could trigger the academic communities in humanities to actively adopt data science in their research and education. Key words: Gustave Jung, Archetype, Character Network Analysis, Digital Humanities, Master characters. 1. INTRODUCTION characters [2]. I have used the R statistical language for computational tools for analysis and visualization. 1.1 General Appearance The outline of this paper is as follows. At the outset, this This paper aims to epitomize the visualization of paper deals with a two-folded theoretical framework drawing character networks on influences and influenced among on (1) character analysis from Jungian archetype and (2) Jungian character archetypes in developing character network analysis in digital humanities. -

An Introduction to Psychological Type

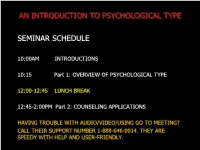

AN INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE SEMINAR SCHEDULE 10:00AM INTRODUCTIONS 10:15 Part 1: OVERVIEW OF PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE 12:00-12:45 LUNCH BREAK 12:45-2:00PM Part 2: COUNSELING APPLICATIONS HAVING TROUBLE WITH AUDIO/VIDEO/USING GO TO MEETING? CALL THEIR SUPPORT NUMBER 1-888-646-0014. THEY ARE SPEEDY WITH HELP AND USER-FRIENDLY. WHAT TO TRY IF YOU CAN’T SEE OR HEAR THE VIDEOS I AM STREAMING FROM GO TO MEETING. STEP 1: DOWNLOAD THE SLIDES I SENT EARLIER THIS WEEK. MOVE TO THE SLIDE I AM DISCUSSING. STEP 2: CLICK ON THE VIDEO LINK ON THE SLIDE. THE YOU TUBE VIDEO SHOULD OPEN AND PLAY ON YOUR COMPUTER. BE SURE TO MUTE YOUR MICROPHONE WHILE DOING THIS. CONFIDENTIALITY YOU WILL HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY TO SHARE PERSONAL INFORMATION ABOUT YOURSELF DURING THIS SEMINAR. AS THE SEMINAR IS BEING RECORDED, SHARE ONLY INFORMATION THAT YOU DON’T MIND BEING RECORDED. DURING PART 2 OF THIS SEMINAR I WILL TURN THE RECORDING OFF WHILE DOING A DEMONSTRATION OF HOW TO CONDUCT A PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE INTERVIEW SO THAT MORE PERSONAL SHARING MAY OCCUR. AAMFT ETHICAL GUIDELINES REGARDING CONFIDENTIALITY WILL APPLY TO PERSONAL INFORMATION SHARED. ICEBREAKER WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER TO BE YOUR GREATEST STRENGTHS AS A PERSON? RECENT EXAMPLE OF THAT? AN INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE Dr. Carl Jung One of the most important of Jung's longer works, and probably the most famous of his books, Psychological Types appeared in German in 1921 after a "fallow period" of eight years during which Jung had published little. He called it "the fruit of nearly twenty years' work in the domain of practical psychology," and in his autobiography he wrote: "This work sprang originally from my need to define the ways in which my outlook differed from Freud's and Adler's.