Delta Sources and Resources ...134 Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

Northeast Arkansas Edition DECEMBER 2020-2021

Find It Here. Northeast Arkansas Edition DECEMBER 2020-2021 We’re on the web! Use our online directory at Ritter411.com 870.358.4400 rittercommunications.com Emergency & Information Numbers Write in the telephone numbers you will need in case of an emergency. Obtain your Police and Fire Department numbers from the list below. Local Police _________________________________ Doctor _______________ State Police _________________________________ Ambulance _______________ Fire _________________________________ ________ In counties where enhanced 9-1-1 service is not available, calls are transferred to a local law enforcement agency. Police Marked Tree . Dial 358-2024 Lepanto . Dial 475-2566 Tyronza . Dial 487-2168 Keiser . Dial 526-2300 Dyess . Dial 764-2101 Etowah . Dial 531-2340 Fire Marked Tree . Dial 358-3131 Lepanto . Dial 475-6030 Tyronza . Dial 487-2103 Keiser . Dial 526-2300 Dyess . Dial 764-2211 Etowah . Dial 531-2540 Sheriff Department Poinsett County . .(Toll Call) 1-870-578-5411 Mississippi County . .(Toll Call) 1-870-658-2242 1 How To Reach Us Cable Location – Call us Before you Dig Before you dig in areas where telephone cables are buried, please call our repair service first at 1-888-336-4466 or the Arkansas One Call System at 811 or 1-800-482-8998 where the personnel will locate any cables in the area free of charge. A cut cable causes trouble, added costs and service blackouts. The calls and conversations you cut off can be someone with a health emergency trying to get aid, someone trying to reach the fire or police department or a customer with an important business call. -

Commonlit | Showdown in Little Rock

Name: Class: Showdown in Little Rock By USHistory.org 2016 This informational text discusses the Little Rock Nine, a group of nine exemplary black students chosen to be the first African Americans to enroll in an all-white high school in the capital of Arkansas, Little Rock. Arkansas was a deeply segregated southern state in 1954 when the Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The Little Rock Crisis in 1957 details how citizens in favor of segregation tried to prevent the integration of the Little Rock Nine into a white high school. As you read, note the varied responses of Americans to the treatment of the Little Rock Nine. [1] Three years after the Supreme Court declared race-based segregation illegal, a military showdown took place in the capital of Arkansas, Little Rock. On September 3, 1957, nine black students attempted to attend the all-white Central High School. The students were legally enrolled in the school. The National Association for the Advancement of "Robert F. Wagner with Little Rock students NYWTS" by Walter Colored People (NAACP) had attempted to Albertin is in the public domain. register students in previously all-white schools as early as 1955. The Little Rock School Board agreed to gradual integration, with the Superintendent Virgil Blossom submitting a plan in May of 1955 for black students to begin attending white schools in September of 1957. The School Board voted unanimously in favor of this plan, but when the 1957 school year began, the community still raged over integration. When the black students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” attempted to enter Central High School, segregationists threatened to hold protests and physically block the students from entering the school. -

White Backlash in the Civil Rights Movement: a Study of the White Responses to the Little Rock Crisis of 1957 Abby Motycka, Clas

White Backlash in the Civil Rights Movement: A Study of the White Responses to the Little Rock Crisis of 1957 Abby Motycka, Class of 2017 For my honors project in the Africana Studies Department I decided to research the response from white southern citizens during the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. I want to explain the significance of Little Rock and its memorable story of desegregation broadcasted across the nation. Little Rock was in many ways the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement and a representation of tension between state and federal governments. The population shifted to appear predominantly segregationist and actively invested in halting plans for integration. Many white citizens chose not to participate, but others chose to join violent, vicious mobs. The complex environment leading up to the crisis of Little Rock was unexpected given the city’s reputation of liberality and particularly progressive southern Governor. No one could have predicted the nation’s first massive backlash to Brown v. Board of Education to be ignited in the small capitol of Arkansas or foreseen the mob violence that would follow. Analyzing white southern responses to African Americans at this time exposes the many dangerous ideologies and practices associated with American culture. Little Rock provides a specific location and event to compare to the other significant moments of white counter protest events in Birmingham, Montgomery, and Atlanta. I want to know how the white population evolved from moderate to outspoken on issues of education over the already integrated bus systems and stores. In my project, I explore approaches the white administration chose to take, including the School Board and the state government, to explain the initial and evolving response the state of Arkansas had to the Brown v. -

Alliance of Arkansas 2013 Arkansas Preservation Awards Program Reception

Historic Alliance of Arkansas 2013 Arkansas Preservation Awards Program Reception Welcome Courtney Crouch III / President, Historic Preservation Alliance Dinner Remarks John T. Greer Jr., AIA, LEED AP / Past President and Awards Selection Committee Chair Awards Program Rex Nelson, Master of Ceremonies Awards presented by Courtney Crouch III Closing Remarks Vanessa McKuin / Executive Director, Historic Preservation Alliance Sponsors & Patrons Special Thanks Bronze Sponsors Special thanks to: Holly Frein Parker Westbrook Laura Gilson Missy McSwain Table Sponsors Caroline Millar Greg Phillips Susan Shaddox Cary Tyson Amara Yancey Additional Table Sponsors Courtney Crouch Jr. & Brenda Crouch Ann McSwain Patrons Ted & Leslie Belden Brister Construction Richard C. Butler Jr. William Clark, Clark Contractors W.L. Cook Courtney C. Crouch III & Amber Crouch Energy Engineering Consultants Senator Keith Ingram Representative Walls McCrary and Emma McCrary The Honorable Robert S. Moore and Beverly Bailey Moore Justice and David Newbern Mark and Cheri Nichols WER Architects/Planners Additional support provided by: Theodosia Murphy Nolan Golden Eagle of Arkansas Lifetime Achievement Award Recipients Named in honor of the Alliance’s Founding President, the Parker Westbrook Parker Westbrook Award for Lifetime Achievement Award recognizes significant individual achievement in historic preservation. It is Award – Frances “Missy” McSwain, Lonoke the Alliance’s only award for achievement in preservation over a period of years. The award may be presented to an individual, organization, business or public Excellence in Heritage Preservation Award agency whose activity may be of local, statewide or regional importance. Award – Delta Cultural Center, Helena Recipients of the Parker Westbrook Award for Lifetime Achievement Excellence in Preservation through Rehabilitation 1981 Susie Pryor, Camden Award – Fort Smith Regional Art Museum, Fort Smith Large Project – Mann on Main, Little Rock Edwin Cromwell, Little Rock 1982 Small Project – Lesmeister Guesthouse, Pocahontas 1983 Dr. -

Choices in LITTLE ROCK

3434_LittleRock_cover_F 5/27/05 12:58 PM Page 1 Choices IN LITTLE ROCK A FACING HISTORY AND OURSELVES TEACHING GUIDE ••••••••• CHOICES IN LITTLE ROCK i Acknowledgments Facing History and Ourselves would like to offer special thanks to The Yawkey Foundation for their support of Choices in Little Rock. Facing History and Ourselves would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance it received from the Boston Public Schools in creating Choices in Little Rock. We are particularly appreciative of the team that consulted on the development of the unit under the leadership of Sidney W. Smith, Director, Curriculum and Instructional Practices, and Judith Berkowitz, Ed.D., Project Director for Teaching American History. Patricia Artis, history coach Magda Donis, language acquisitions coach Meira Levinson, Ph.D., teacher, McCormack Middle School Kris Taylor, history coach Mark Taylor, teacher, King Middle School Facing History and Ourselves would also like to offer special thanks to the Boston Public School teachers who piloted the unit and provided valuable suggestions for its improvement. Constance Breeden, teacher, Irving Middle School Saundra Coaxum, teacher, Edison Middle School Gary Fisher, teacher, Timilty Middle School Adam Gibbons, teacher, Lyndon School Meghan Hendrickson, history coach, former teacher, Dearborn Middle School Wayne Martin, Edwards Middle School Peter Wolf, Curley Middle School Facing History and Ourselves values the efforts of its staff in producing and implementing the unit. We are grateful to Margot Strom, Marc Skvirsky, Jennifer Jones Clark, Fran Colletti, Phyllis Goldstein, Jimmie Jones, Melinda Jones-Rhoades, Tracy O’Brien, Jenifer Snow, Jocelyn Stanton, Chris Stokes, and Adam Strom. Design: Carter Halliday Associates www.carterhalliday.com Printed in the United States of America 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 November 2009 ISBN-13: 978-0-9798440-5-8 ISBN-10: 0-9798440-5-3 Copyright © 2008 Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. -

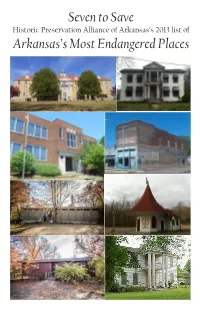

2013 MEP Press Packet

Seven to Save Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas’s 2013 list of Arkansas’s Most Endangered Places About the Most Endangered Places Program The Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas began Arkansas’s Most Endangered Places program in 1999 to raise awareness of the importance of Arkansas’s historic properties and the dangers they face through neglect, encroaching development, and loss of integrity. The list is updated each year and serves to generate discussion and support for saving the state’s endangered historic places. Previous places listed include the Johnny Cash Boyhood Home and the Dyess Colony Administration Building in Dyess, Bluff Shelter Archaeological Sites in Northwest Arkansas, Rohwer and Jerome Japanese-American Relocation Camps in Desha County, the William Woodruff House in Little Rock, Magnolia Manor in Arkadelphia, Centennial Baptist Church in Helena, the Donaghey Buildings in Little Rock, the Saenger Theatre in Pine Bluff, the twentieth century African American Rosenwald Schools throughout the state, the Mountainaire Apartments in Hot Springs, Forest Fire Lookouts statewide, the Historic Dunbar Neighborhood in Little Rock, Carleson Terrace in Fayetteville, the Woodmen on Union Building in Hot Springs. Properties are nominated by individuals, communities, and organizations interested in preserving these places for future Arkansans. Criteria for inclusion in the list includes a property’s listing or eligibility for listing in the Arkansas or National Register of Historic Places; the degree of a property’s local, state or national significance; and the imminence and degree of the threat to the property. The Historic Preservation Alliance of Arkansas was founded in 1981 and is the only statewide nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving Arkansas’s architectural and cultural heritage. -

Reflections on the Little Rock Desegregation Crisis

Louisiana State University Law Center LSU Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1989 Confrontation as Rejoinder to Compromise: Reflections on the Little Rock Desegregation Crisis Raymond T. Diamond Louisiana State University Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Diamond, Raymond T., "Confrontation as Rejoinder to Compromise: Reflections on the Little Rock Desegregation Crisis" (1989). Journal Articles. 290. https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship/290 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES CONFRONTATION AS REJOINDER TO COMPROMISE: REFLECTIONS ON THE LITTLE ROCK DESEGREGATION CRISIS* Raymond T. Diamond** In September 1957, soldiers of the IOI st Airborne Division of the United Stat es Army were called to duty in hostile territory. These soldiers were called to Little Rock, Arkansas, to keep safe nine Black children who, under a court order of desegregation, attended Little Rock's Central High School. 1 The Little Rock crisis is writ large in the history of the desegregation of the American South. Because many of the events of the crisis were performed before the television camera at a time when television was new, the Little Rock crisis was etched graphically in the American consciousness. 2 The cam era showed in violent detail the willingness of the South to maintain segrega tion, and the willingness of the federal government to support federal law. -

Little Rock Nine

Little Rock Nine Few people know their names, but the nine black students who became known as the Little Rock Nine helped to bring widespread integration to public schools in the United States. In the fall of 1957, Americans who were impressed with their courage and curious about the confrontations they caused watched as these ninestudents braved repeated threats and other indignities from segregationists as they tried to attend classes at the all-white Little Rock Central High School. The determination of the Little Rock Nine in challenging Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, who used armed troops to bar the nine students from entering the school, is legendary. Despite the obstacles they faced, the Little Rock Nine eventually entered the school and were able to attend classes, and as they did, their experiences continued to be documented and preserved as a testament to their characters. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional and that school systems should begin plans to desegregate. However, during the early years of his administration, President Dwight D. Eisenhower did not focus on education and, therefore, many states were slow to implement plans for or actively to pursue desegregation. Civil rights organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) continued to pressure state and federal officials about integration while implementing their own plans to facilitate the process. The Arkansas state president of the NAACP, Daisy Bates (who was elected in 1952), organized a youth council that included the first ninestudents to desegregate Little Rock Central High. -

September 2012

Celebrating Rural Money Trumps Easy Back-To-School Electrification p. 4 Tradition p. 24 Recipes p. 34 www.ecark.org SEPTEMBER 2012 Lee & BertheLLa $$50,00050,000 thomas Energy Efficiency Grand Prize Winners MAKEMAKEOOVEVERR SEPTEMBER 2012 ARKANSAS LIVING I 1 WATERFURNACE UNITS QUALIFY FOR A 30% FEDERAL TAX CREDIT and it isn’t just corn. You may not realize it, but your home is sitting on a free and renewable supply of energy. A WaterFurnace geothermal comfort system taps into the stored solar energy in your own backyard to provide savings of up to 70% on heating, cooling and hot water. That’s money in the bank and a smart investment in your family’s comfort. Contact your local WaterFurnace dealer today to learn how to tap into your buried treasure. YOUR LOCAL WATERFURNACE DEALERS Brookland DeQueen Mountain Home Russellville Nightingale Mechanical Bill Lee Co. Custom Heating & Cooling Rood Heating & Air (870) 933-1200 (870) 642-7127 (870) 425-9498 (479) 968-3131 Cabot Hot Springs Central Heating & Air Springdale Stedfast Heating & Air GTS Inc. (870) 425-4717 Paschal Heat, Air & (501) 843-4860 (501) 760-3032 Plumbing (800) 933-0195 waterfurnace.com (800) GEO-SAVE 2 I ARKANSAS LIVING ©2012 WaterFurnace is a registered trademark of WaterFurnace International, Inc. SEPTEMBER 2012 WATERFURNACE UNITS QUALIFY FOR A 30% FEDERAL TAX CREDIT (ISSN 0048-878X) (USPS 472960) Arkansas Living is published monthly. CONTENTS Periodicals postage paid at Little Rock, AR and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: Arkansas Living, P.O. Box 510, Little Rock, AR 72203 Members: Please send name of your cooperative with mailing label. -

Little Rock Nine

National Park Service Little Rock Central U.S. Department of the Interior Little Rock Central High School High School National Historic Site The Little Rock Nine The Little Rock Nine in front of Central High School, September 25, 1997. The Nine are l to r: Thelma Mothershed Wair, Minnijean Brown Trickey, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, and Melba Pattillo Beals. Behind the Nine are, l to r: Little Rock Mayor Jim Dailey, Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee, and President William Jefferson Clinton. Photo by Isaiah Trickey. Who Are The Little Rock In 1957, nine ordinary teenagers walked out of their homes and stepped up to the front Nine? lines in the battle for civil rights for all Americans. The media coined the name “Little Rock Nine,” to identify the first African-American students to desegregate Little Rock Central High School. The End of Legal In 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka “[Blossom said] you’re not going to be able to go Segregation Supreme Court decision outlawed segregation in to the football games or basketball games. You’re public education. Little Rock School District not going to be able to participate in the choir or Superintendent Virgil Blossom devised a plan of drama club, or be on the track team. You can’t go gradual integration that would begin at Central to the prom. There were more cannots…” High School in 1957. The school board called for Carlotta Walls LaNier volunteers from all-black Dunbar Junior High and Horace Mann High School to attend Central. -

Arkansas Public Higher Education Operating & Capital

Arkansas Public Higher Education Operating & Capital Recommendations 2019-2021 Biennium 7-A Volume 1 Universities Arkansas Department of Higher Education 423 Main Street, Suite 400, Little Rock, Arkansas 72201 October 2018 ARKANSAS PUBLIC HIGHER EDUCATION OPERATING AND CAPITAL RECOMMENDATIONS 2019-2021 BIENNIUM VOLUME 1 OVERVIEW AND UNIVERSITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTITUTIONAL ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................................... 1 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EDUCATIONAL AND GENERAL OPERATIONS ................................................................................... 3 Background ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Table A. Summary of Operating Needs & Recommendations for the 2019-2021 Biennium .............................................................. 7 Table B. Year 2 - Productivity Index ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Table C. 2019-21 Four-Year Universities Recommendations ........................................................................................................... 9 Table D. 2019-21 Two-Year Colleges Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 10 Table E. 2019-21