Choices in LITTLE ROCK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Association for Women in Mathematics: How and Why It Was

Mathematical Communities t’s 2011 and the Association for Women in Mathematics The Association (AWM) is celebrating 40 years of supporting and II promoting female students, teachers, and researchers. It’s a joyous occasion filled with good food, warm for Women conversation, and great mathematics—four plenary lectures and eighteen special sessions. There’s even a song for the conference, titled ‘‘((3 + 1) 9 3 + 1) 9 3 + 1 Anniversary in Mathematics: How of the AWM’’ and sung (robustly!) to the tune of ‘‘This Land is Your Land’’ [ICERM 2011]. The spirit of community and and Why It Was the beautiful mathematics on display during ‘‘40 Years and Counting: AWM’s Celebration of Women in Mathematics’’ are truly a triumph for the organization and for women in Founded, and Why mathematics. It’s Still Needed in the 21st Century SARAH J. GREENWALD,ANNE M. LEGGETT, AND JILL E. THOMLEY This column is a forum for discussion of mathematical communities throughout the world, and through all time. Our definition of ‘‘mathematical community’’ is Participants from the Special Session in Number Theory at the broadest: ‘‘schools’’ of mathematics, circles of AWM’s 40th Anniversary Celebration. Back row: Cristina Ballantine, Melanie Matchett Wood, Jackie Anderson, Alina correspondence, mathematical societies, student Bucur, Ekin Ozman, Adriana Salerno, Laura Hall-Seelig, Li-Mei organizations, extra-curricular educational activities Lim, Michelle Manes, Kristin Lauter; Middle row: Brooke Feigon, Jessica Libertini-Mikhaylov, Jen Balakrishnan, Renate (math camps, math museums, math clubs), and more. Scheidler; Front row: Lola Thompson, Hatice Sahinoglu, Bianca Viray, Alice Silverberg, Nadia Heninger. (Photo Cour- What we say about the communities is just as tesy of Kiran Kedlaya.) unrestricted. -

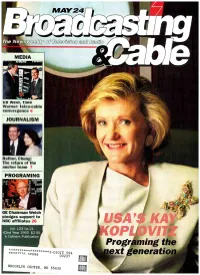

Ext Generatio

MAY24 The News MEDIA nuo11011 .....,1 US West, Time Warner: telco-cable convergence 6 JOURNALISM Rather, Chung: The return of the anchor team PROGRAMING GE Chairman Welch pledges support to NBC affiliates 26 U N!'K; Vol. 123 No.21 62nd Year 1993 $2.95 A Cahners Publication OP Progr : ing the no^o/71G,*******************3-DIGIT APR94 554 00237 ext generatio BROOKLYN CENTER, MN 55430 Air .. .r,. = . ,,, aju+0141.0110 m,.., SHOWCASE H80 is a re9KSered trademark of None Box ice Inc. P 1593 Warner Bros. Inc. M ROW Reserve 5H:.. WGAS E ALE DEMOS. MEN 18 -49 MEN 18 -49 AUDIENCE AUDIENCE PROGRAM COMPOSITION PROGRAM COMPOSITION STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE 9 37% WKRP IN CINCINNATI 25% HBO COMEDY SHOWCASE 35% IT'S SHOWTIME AT APOLLO 24% SATURDAY NIGHT LIVE 35% SOUL TRAIN 24% G. MICHAEL SPORTS MACHINE 34% BAYWATCH 24% WHOOP! WEEKEND 31% PRIME SUSPECT 24% UPTOWN COMEDY CLUB 31% CURRENT AFFAIR EXTRA 23% COMIC STRIP LIVE 31% STREET JUSTICE 23% APOLLO COMEDY HOUR 310/0 EBONY JET SHOWCASE 23% HIGHLANDER 30% WARRIORS 23% AMERICAN GLADIATORS 28% CATWALK 23% RENEGADE 28% ED SULLIVAN SHOW 23% ROGGIN'S HEROES 28% RUNAWAY RICH & FAMOUS 22% ON SCENE 27% HOLLYWOOD BABYLON 22% EMERGENCY CALL 26% SWEATING BULLETS 21% UNTOUCHABLES 26% HARRY & THE HENDERSONS 21% KIDS IN THE HALL 26% ARSENIO WEEKEND JAM 20% ABC'S IN CONCERT 26% STAR SEARCH 20% WHY DIDN'T I THINK OF THAT 26% ENTERTAINMENT THIS WEEK 20% SISKEL & EBERT 25% LIFESTYLES OF RICH & FAMOUS 19% FIREFIGHTERS 25% WHEEL OF FORTUNE - WEEKEND 10% SOURCE. NTI, FEBRUARY NAD DATES In today's tough marketplace, no one has money to burn. -

Exchange with Reporters Prior to Discussions with Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland of Norway May 17, 1994

May 16 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1994 give our kids a safe and decent and well-edu- We cannot stand chaos and destruction, but cated childhood to put things back together we must not embrace hatred and division. We again. There is no alternative for us if we want have only one choice. to keep this country together and we want, 100 Let me read this to you in closing. It seems years from now, people to celebrate the 140th to me to capture the spirit of Brown and the anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education in spirit of America and what we have to do today, the greatest country the world has ever known, starting with what is in our heart. These are fully diverse, where everybody, all God's chil- lines from Langston Hughes' wonderful poem dren, can live up to the fullest of their God- ``Let America Be America Again'': ``Oh yes, I given potential. say it plain, America never was America to me. And in order to do it, we all have to overcome And yet I swear this oath, America will be.'' a fair measure not only of fear but of resigna- Let that be our oath on this 40th anniversary tion. There are so many of us today, and all celebration. of us in some ways at some times, who just Thank you, and God bless you all. don't believe we can tackle the big things and make a difference. But I tell you, the only thing for us to do to honor those whom we honor NOTE: The President spoke at 8:15 p.m. -

A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael

South Carolina Law Review Volume 62 Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2010 A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael Lonnie T. Brown Jr. University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lonnie T. Brown, Jr., A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael, 62 S. C. L. Rev. 1 (2010). This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brown: A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Select A TALE OF PROSECUTORIAL INDISCRETION: RAMSEY CLARK AND THE SELECTIVE NON-PROSECUTION OF STOKELY CARMICHAEL LONNIE T. BROWN, JR.* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 II. THE PROTAGONISTS .................................................................................... 8 A. Ramsey Clark and His Civil Rights Pedigree ...................................... 8 B. Stokely Carmichael: "Hell no, we won't go!.................................. 11 III. RAMSEY CLARK'S REFUSAL TO PROSECUTE STOKELY CARMICHAEL ......... 18 A. Impetus Behind Callsfor Prosecution............................................... 18 B. Conspiracy to Incite a Riot.............................................................. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

What We Give, However, Mgkes a Lve. -Arthur Ashe 2 THETUFTS DAILY Commencement 1999

THEWhere You Read It First TUFTS Commencement 1999 DAILY Volume XXXVIII, Number 63 , From what we get, we can make a living; what we give, however, mGkes a lve. -Arthur Ashe 2 THETUFTS DAILY Commencement 1999 News pages 345 A historical perspective of the Tufts endowment Is cheating running rampant at Tufts? New alumni will be able to keep in touch with e-mail Tufts students appear on The Lafe Show wifh David Lefferman A retrospective of the last four years Ben Zaretskyfears graduation in his final column Sports Vivek Ramgopal profiles retiring Athletic Director Rocky Carzo Baseball just misses out in the post-season 8 \( 11 b .7\ c/ Viewpoints - c Dan Pashman encourages Tuftonians to appreciate the school Commencement speakerAlex Shalom's Wendell Phillips speech David Mamet's new movie The Winslow Boy and an interview with the director A review of the new Beelzebubs CD, Infinity A review of The Castle and Trippin' Photo by Kate Cohen f Cover Photo by Seth Kaufman + < THETUFTS DAILYCommencement 1999 3 NEWS Halberstam, Ackerman speak 1929 1978 1999 Tufts $9.7 million $30 million $500 million DartmoLth $9.7 million $1 57 million $1.4 billion Brown $9.4 million $96 million $1.1 billion at Tufts’ Commencement ‘99 Alex Shalom to give coveted Wendell Phillips speech byILENEsllEIN Best and the Brightest, about the ment address. Senior Staff Writer Vietnam War, and most recently The ceremonies for the indi- Percent increase Percent increase Nearly 1,700 undergraduates Playingfor Keeps, a biography of vidual schools will take place be- between ’29 and between ’78 and and graduates will gather on the Michael Jordan. -

Lee Lorch 1915-2014

Extract from OP-SF NET Topic #1 --------- OP-SF NET 21.2 -------- March 15, 2014 From: Martin Muldoon [email protected] Subject: Lee Lorch 1915-2014 Lee Lorch died in Toronto on February 28, 2014 at the age of 98. He was known as a mathematician who made life-long contributions to ending segregation in housing and education and to the improving the position of women and minorities in mathematics. Born in New York City on September 20, 1915, Lorch was educated at Cornell University (1931-35) and at the University of Cincinnati (1935-41) where he completed his PhD under the supervision of Otto Szász, with a thesis “Some Problems on the Borel Summability of Fourier Series”. He worked for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (the predecessor of NASA) in 1942-42 and served in the US Army in India and the Pacific in 1943-46. While In India, he took time to contact local mathematicians and his second publication appeared in the Bulletin of the Calcutta Mathematical Society (1945). Some of Lorch’s early mathematical work, arising from the subject of his thesis dealt with the magnitude and asymptotics of the Lebesgue constants, known to form a divergent sequence in the case of Fourier Series. He studied the corresponding question when convergence is replaced by various kinds of summability (Fejér had considered Cesàro summability) in several papers including joint work with Donald J. Newman (whom he had known as an undergraduate at CUNY in the late 1940s). Later, he looked at corresponding questions for Jacobi series. At the same time, Lee and his wife Grace were involved in the struggle against discrimination in housing (in New York), for equal treatment for Blacks in mathematical meetings, and for school integration in the US South. -

A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1994 A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement Michelle Margaret Viera Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Viera, Michelle Margaret, "A Summary of the Contributions of Four Key African American Female Figures of the Civil Rights Movement" (1994). Master's Theses. 3834. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3834 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SUMMARY OF THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF FOUR KEY AFRICAN AMERICAN FEMALE FIGURES OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by Michelle Margaret Viera A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1994 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My appreciation is extended to several special people; without their support this thesis could not have become a reality. First, I am most grateful to Dr. Henry Davis, chair of my thesis committee, for his encouragement and sus tained interest in my scholarship. Second, I would like to thank the other members of the committee, Dr. Benjamin Wilson and Dr. Bruce Haight, profes sors at Western Michigan University. I am deeply indebted to Alice Lamar, who spent tireless hours editing and re-typing to ensure this project was completed. -

2006-2007 Impact Report

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S MEDIA FOUNDATION The Global Network for Women in the News Media 2006–2007 Annual Report From the IWMF Executive Director and Co-Chairs March 2008 Dear Friends and Supporters, As a global network the IWMF supports women journalists throughout the world by honoring their courage, cultivating their leadership skills, and joining with them to pioneer change in the news media. Our global commitment is reflected in the activities documented in this annual report. In 2006-2007 we celebrated the bravery of Courage in Journalism honorees from China, the United States, Lebanon and Mexico. We sponsored an Iraqi journalist on a fellowship that placed her in newsrooms with American counterparts in Boston and New York City. In the summer we convened journalists and top media managers from 14 African countries in Johannesburg to examine best practices for increasing and improving reporting on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria. On the other side of the world in Chicago we simultaneously operated our annual Leadership Institute for Women Journalists, training mid-career journlists in skills needed to advance in the newsroom. These initiatives were carried out in the belief that strong participation by women in the news media is a crucial part of creating and maintaining freedom of the press. Because our mission is as relevant as ever, we also prepared for the future. We welcomed a cohort of new international members to the IWMF’s governing board. We geared up for the launch of leadership training for women journalists from former Soviet republics. And we added a major new journalism training inititiative on agriculture and women in Africa to our agenda. -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

The All American Boy

The All American Boy His teeth I remember most about him. An absolutely perfect set kept totally visible through the mobile shutter of a mouth that rarely closed as he chewed gum and talked, simultaneously. A tricky manoeuvre which demanded great facial mobility. He was in every way the epitome of what the movies, and early TV had taught me to think of as the “All American Boy”. Six foot something, crew cut hair, big beaming smile, looked to be barely twenty. His mother must have been very proud of him! I was helping him to refuel the Neptune P2V on the plateau above Wilkes from numerous 44 gallon drums of ATK we had hauled to the “airstrip” on the Athey waggon behind a D4 driven by Max Berrigan. I think he was an aircraft mechanic. He and eight of his compatriots had just landed after a flight from Mirny, final stop McMurdo. Somehow almost all of the rest of his crew, and ours, had hopped into the weasels to go back to base for a party, leaving just a few of us “volunteers” to refuel. I remember too, feeling more than a little miffed when one of the first things he said after our self- introductions was “That was one hell of a rough landing strip you guys have - nearly as bad as Mirny”. Poor old Max had ploughed up and down with the D4 for hours knocking the tops of the Sastrugi and giving the “strip” as smooth a surface as he could. For there was not really a strip at Wilkes just a slightly flatter area of plateau defined by survey pegs. -

Address at Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., Delivered by Coretta Scott King the Martin Luther King, Jr. P

25 Oct vividly, is the vast outpouring of sympathy and affection that came to me literally 1958 from everywhere-from Negro and white, from Catholic, Protestant and Jew, from the simple, the uneducated, the celebraties and the great. I know that this affection was not for me alone. Indeed it was far too much for any one man to de- serve. It was really for you. It was an expression of the fact that the Montgomery Story had moved the hearts of men everywhere. Through me, the many thou- sands of people who wrote of their admiration, were really writing of their love for you. This is worth remembering. This is worth holding on to as we strive on for Freedom. And finally, as I indicated before, the experience I had in New York gave me time to think. I believe that I have sunk deeper the roots of my convic- tion that (non-violent}resistence is the true path for overcoming in- justice and- for stamping out evil. May God bless you. TAD. MLKP-MBU: Box 93. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project Address at Youth March for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C., Delivered by Coretta Scott King 25 October 1958 New York, N.Y. At the Lincoln Memorial Coretta Scott King delivered these remarks on behalf of her husband to ten thousand people who had marched down Constitution Avenue in support of school integration.’ During the march Harry Belafonte led a small integrated contingent of students to the White House to meet the president. They were met at the gate by a guard who informed them that neither the president nor any of his assistants would be available.