A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strengths Become Vulnerabilities How a Digital World Disadvantages the United States in Its International Relations

A HOOVER INSTITUTION ESSAY Strengths Become Vulnerabilities HOW A DIGITAL WORLD DISadVANTAGES THE UNITED STATES IN ITS INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JACK GOLDSMITH AND STUART RUSSELL Aegis Series Paper No. 1806 The Roman Empire’s multi-continent system of roads effectuated and symbolized Roman military, economic, and cultural power for centuries. Those same roads were eventually used as a pathway for the Goths to attack and destroy the empire.1 The Internet and related digital systems that the United States did so much to create have effectuated and symbolized US military, economic, and cultural power for decades. The question raised by this essay is whether these systems, like the Roman Empire’s roads, will come to be seen as a platform that accelerated US decline. We are not so foolish as to predict that this will happen.2 But this essay does seek to shine light on the manifold and, in the aggregate, underappreciated structural Law and Technology, Security, National challenges that digital systems increasingly present for the United States, especially in its relations with authoritarian adversaries. These problems arise most clearly in the face of the “soft” cyber operations that have been so prevalent and damaging in the United States in recent years: cyber espionage, including the digital theft of public- and private-sector secrets; information operations and propaganda, related to elections; doxing, which is the theft and publication of private information; and relatively low-level cyber disruptions such as denial-of-service and ransomware attacks.3 Our central claim is that the United States is disadvantaged in the face of these soft cyber operations due to constitutive and widely admired features of American society, including the nation’s commitment to free speech, privacy, and the rule of law; its innovative technology firms; its relatively unregulated markets; and its deep digital sophistication. -

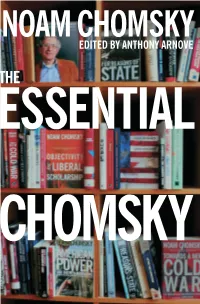

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 2-2-1968 Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968" (1968). Resist Newsletters. 4. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/4 a call to resist illegitimate authority .P2bruar.1 2 , 1~ 68 -763 Maasaohuaetta A.Tenue, RH• 4, Caabrid«e, Jlaaa. 02139-lfewaletter I 5 THE ARRAIGNMENTS: Boston, Jan. 28 and 29 Two days of activities surrounded the arraignment for resistance activity of Spock, Coffin, Goodman, Ferber and Raskin. On Sunday night an 'Interfaith Service for Consci entious Dissent' was held at the First Church of Boston. Attended by about 700 people, and addressed by clergymen of the various faiths, the service led up to a sermon on 'Vietnam and Dissent' by Rev. William Sloane Coffin. Later that night, at Northeastern University, the major event of the two days, a rally for the five indicted men, took place. An overflow crowd of more than 2200 attended the rally,vhich was sponsored by a broad spectrum of organizations. The long list of speakers included three of the 'Five' - Spock (whose warmth, spirit, youthfulness, and toughness clearly delight~d an understandably sympathetic and enthusiastic aud~ence), Coffin, Goodman. Dave Dellinger of Liberation Magazine and the National Mobilization Co11111ittee chaired the meeting. The other speakers were: Professor H. Stuart Hughes of Ha"ard, co-chairman of national SANE; Paul Lauter, national director of RESIST; Bill Hunt of the Boston Draft Resistance Group, standing in for a snow-bound liike Ferber; Bob Rosenthal of Harvard and RESIST who announced the formation of the Civil Liberties Legal Defense Fund; and Tom Hayden. -

The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at the Breman Museum

William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History Weinberg Center for Holocaust Education THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES FOR SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY AT THE BREMAN MUSEUM MSS 250, CECIL ALEXANDER PAPERS BOX 1, FILE 10 BIOGRAPHY, 2000 THIS PROJECT WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS SUPPORT OF THE ALEXANDER FAMILY ANY REPRODUCTION OF THIS MATERIAL WITHOUT THE EXPRESSED WRITTEN CONSENT OF THE CUBA FAMILY ARCHIVES IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED The William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum ● 1440 Spring Street NW, Atlanta, GA 30309 ● (678) 222-3700 ● thebreman.org CubaFamily Archives Mss 250, Cecil Alexander Papers, The Cuba Family Archives for Southern Jewish History at The Breman Museum. THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCIDTECTS October 2, 2000 Ben R. Danner, FAIA Director, Sowh Atlantic Region Mr. Stephen Castellanos, FAIA Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award C/o AlA Honors and Awards Department I 735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20006-5292 Dear Mr. Castellanos: It is my distinct privilege to nominate Cecil A. Alexander, FAIA for the Whitney M. Young, Jr. Award. Mr. Alexander is a man whose life exemplifies the meaning of the award. He is a distinguished architect who has led the effort to foster better understanding among groups and promote better race relations in Atlanta. Cecil was a co-founder, with Whitney Young, of Resurgens Atlanta, a group of civic and business leaders dedicated to improving race relations that has set an example for the rest of the nation. Cecil was actively involved with social issues long before Mr. Young challenged the AlA to assume its professional responsibility toward these issues. -

Sanctuary: a Modern Legal Anachronism Dr

SANCTUARY: A MODERN LEGAL ANACHRONISM DR. MICHAEL J. DAVIDSON* The crowd saw him slide down the façade like a raindrop on a windowpane, run over to the executioner’s assistants with the swiftness of a cat, fell them both with his enormous fists, take the gypsy girl in one arm as easily as a child picking up a doll and rush into the church, holding her above his head and shouting in a formidable voice, “Sanctuary!”1 I. INTRODUCTION The ancient tradition of sanctuary is rooted in the power of a religious authority to grant protection, within an inviolable religious structure or area, to persons who fear for their life, limb, or liberty.2 Television has Copyright © 2014, Michael J. Davidson. * S.J.D. (Government Procurement Law), George Washington University School of Law, 2007; L.L.M. (Government Procurement Law), George Washington University School of Law, 1998; L.L.M. (Military Law), The Judge Advocate General’s School, 1994; J.D., College of William & Mary, 1988; B.S., U.S. Military Academy, 1982. The author is a retired Army judge advocate and is currently a federal attorney. He is the author of two books and over forty law review and legal practitioner articles. Any opinions expressed in this Article are those of the author and do not represent the position of any federal agency. 1 VICTOR HUGO, THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE-DAME 189 (Lowell Bair ed. & trans., Bantam Books 1956) (1831). 2 Michael Scott Feeley, Toward the Cathedral: Ancient Sanctuary Represented in the American Context, 27 SAN DIEGO L. REV. -

NOVEMBER 6, 1979 WASHINGTON, D.Cl THME DAY 8:35 A.M

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON, D.C. 5:30 a.m. TUESDAY From 1 To 5:30 The President received a wake up call from the White House signal board operator. 6:02 The President went to the Oval Office. 6:46 6:50 The President talked with Secretary of State Cyrus R. Vance. The President telephoned Secretary. Vance. The call was not completed. 7:ll The President talked with Secretary Vance. 7:ll 7:12 The President talked with his Press Secretary, Joseph L. "Jody" Powell. IA6 7:22 The President talked with Coretta Scott King, President of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Social Change, Atlanta, Georgia. The President met with: 7:30 7:50 Zbigniew Brzezinski, Assistant for National Security Affairs 7:45 ’ 7:50 Walter F. Mondale, Vice President I 7:46 1 7:47 The President talked with his Personal Assistant and Secretary, Susan S. Clough. 7:56 The President talked with Secretary of Defense Harold Brown. The President met to discuss the situation in Iran with: 8:OO 8:30 Secretary Vance 8:00 8:30 Mr. Brzezinski 8:00 I 8:30 1 David D. Newsom, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs 8:00 8:30 Gary Sick, Staff Member, National Security Council (NSC) 8:32 Mr. Powell 8:30 Secretary Brown 8:25 1 8:30 I Hamilton Jordan, Chief of Staff i The President met with: 8:35 Mr. Jordan 5:35 Charles H. Kirbo, partner with King and Spalding Law firm, Atlanta, Georgia 8:35 It Robert H. Strauss, Ambassador at Large - designate continued THE DAlL’f DCARY OF PRESIDENT .llhAMY CARTER OATE WI. -

What We Give, However, Mgkes a Lve. -Arthur Ashe 2 THETUFTS DAILY Commencement 1999

THEWhere You Read It First TUFTS Commencement 1999 DAILY Volume XXXVIII, Number 63 , From what we get, we can make a living; what we give, however, mGkes a lve. -Arthur Ashe 2 THETUFTS DAILY Commencement 1999 News pages 345 A historical perspective of the Tufts endowment Is cheating running rampant at Tufts? New alumni will be able to keep in touch with e-mail Tufts students appear on The Lafe Show wifh David Lefferman A retrospective of the last four years Ben Zaretskyfears graduation in his final column Sports Vivek Ramgopal profiles retiring Athletic Director Rocky Carzo Baseball just misses out in the post-season 8 \( 11 b .7\ c/ Viewpoints - c Dan Pashman encourages Tuftonians to appreciate the school Commencement speakerAlex Shalom's Wendell Phillips speech David Mamet's new movie The Winslow Boy and an interview with the director A review of the new Beelzebubs CD, Infinity A review of The Castle and Trippin' Photo by Kate Cohen f Cover Photo by Seth Kaufman + < THETUFTS DAILYCommencement 1999 3 NEWS Halberstam, Ackerman speak 1929 1978 1999 Tufts $9.7 million $30 million $500 million DartmoLth $9.7 million $1 57 million $1.4 billion Brown $9.4 million $96 million $1.1 billion at Tufts’ Commencement ‘99 Alex Shalom to give coveted Wendell Phillips speech byILENEsllEIN Best and the Brightest, about the ment address. Senior Staff Writer Vietnam War, and most recently The ceremonies for the indi- Percent increase Percent increase Nearly 1,700 undergraduates Playingfor Keeps, a biography of vidual schools will take place be- between ’29 and between ’78 and and graduates will gather on the Michael Jordan. -

Page 1 of 5 Benjamin Spock Conspiracy 7/25/2009

Benjamin Spock Conspiracy Page 1 of 5 excerpt from It Did Happen Here by Bud and Ruth Schultz (University of California Press, 1989) The Conspiracy to Oppose the Vietnam War, Oral History of Benjamin Spock The Selective Service Act of 1948 made it a criminal offense for a person to knowingly counsel, aid, or abet someone in refusing or evading registration in the armed forces. In 1968, Dr. Benjamin Spock and four others were indicted for conspiring to violate this act. Evidence of the conspiracy was to be found in the public expressions of the defendants: hours of selectively edited newsreel footage of press conferences, demonstrations, and public addresses they made in opposition to government policy in Vietnam. What could better symbolize the damage such prosecutions made on the free marketplace of ideas? Why were they charged with conspiracy to counsel, aid, and abet rather than with the commission of those acts themselves? Conspiracy, Judge Learned Hand said, is "the darling of the modern prosecutor's nursery."' It relaxes ordinary rules of evidence, frequently results in higher penalties than the substantive crime, may extend the statue of limitations, and holds all conspirators responsible for the acts of each. The conspirators may have acted entirely in the open, they may never have met; they may have agreed only implicitly; they may never have acted illegally. It's enough that they were of a like mind to do so. When applied to political activity, writing, and speech, a conspiracy charge has virtually no limits. Government attorneys could have included as co-conspirators the publishers of Dr. -

DOJ BACKGROUND/RECORDS A. Key Officials

DOJ BACKGROUND/RECORDS A. Key Officials --Attorney General-- Robert F. Kennedy, 1961-6 Nicholas Katzenbach ? Ramsey Clarke, 196_-__ Griffin Bell (worked with HSCA) --Deputy Attorney General--Nicholas deB. Katzenbach (under Kennedy) --Associate Attorney General --Office of Legislative Affairs --Assistant Attorney General Michael Uhlman, worked with the HSCA --Office of Public Affairs --Office of Policy Development --Office of Information and Privacy --Office of Legal Counsel --Norbert A. Schlei (Assistant AG under Kennedy) --Frank M. Wozencraft (1968) --Assistant Attorney General for Criminal Division --Herbert J. Miller, Jr. (under Kennedy) --Fred M. Vinson, Jr. (@ 1965-68) --Composed of the following sections:General Crimes; Fraud; Organized Crime & Racketeering (the Chief of the Organized Crime Section in 1963 was William G. Hundley); Administrative Regulations (covers immigration); Appeals and Research. --Jeff Fogel was on the JFK Assassination Task Force in 1980 --Internal Security Division --J. Walter Yeagley (under Kennedy and Johnson) --Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Division --John W. Douglas (1965) --Barefoot Sanders (1967) --Edwin Weisl, Jr. (1968) --Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division --Burke Marshall ? (under Kennedy) --John Doar (1967) --Robert Owens (1968) --Assistant Attorney General for the Tax Division --Louis Oberdorfer (under Kennedy) --Robert L. Keuch, Special Counsel to the Attorney General (G. Bell), worked with the HSCA B. Assassination Records Located to Date --Microfilmed DOJ Records from the JFK Library (Need To Review) --Office of Information and Privacy Files re: FOIA Appeals of Harold Weisberg (Civi Action No. 75-0226) and James Lesar, including the documents that were the subject of the appeal. Approximately 3,600 records were identified and 85% transferred to NARA. -

The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’S Fight for Civil Rights

DISCUSSION GUIDE The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights PBS.ORG/indePendenTLens/POWERBROKER Table of Contents 1 Using this Guide 2 From the Filmmaker 3 The Film 4 Background Information 5 Biographical Information on Whitney Young 6 The Leaders and Their Organizations 8 From Nonviolence to Black Power 9 How Far Have We Come? 10 Topics and Issues Relevant to The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights 10 Thinking More Deeply 11 Suggestions for Action 12 Resources 13 Credits national center for MEDIA ENGAGEMENT Using this Guide Community Cinema is a rare public forum: a space for people to gather who are connected by a love of stories, and a belief in their power to change the world. This discussion guide is designed as a tool to facilitate dialogue, and deepen understanding of the complex issues in the film The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights. It is also an invitation to not only sit back and enjoy the show — but to step up and take action. This guide is not meant to be a comprehensive primer on a given topic. Rather, it provides important context, and raises thought provoking questions to encourage viewers to think more deeply. We provide suggestions for areas to explore in panel discussions, in the classroom, in communities, and online. We also provide valuable resources, and connections to organizations on the ground that are fighting to make a difference. For information about the program, visit www.communitycinema.org DISCUSSION GUIDE // THE POWERBROKER 1 From the Filmmaker I wanted to make The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights because I felt my uncle, Whitney Young, was an important figure in American history, whose ideas were relevant to his generation, but whose pivotal role was largely misunderstood and forgotten. -

Jessica Mitford

Jessica Mitford: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Title Jessica Mitford Papers Dates: 1949-1973 Extent 67 document boxes, 3 note card boxes, 7 galley files, 1 oversize folder (27 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, printed material, reports, notes, interviews, manuscripts, legal documents, and other materials represent Jessica Mitford's work on her three investigatory books and comprise the bulk of these papers. Language English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1973 Processed by Donald Firsching, Amanda McCallum, Jana Pellusch, 1990 Repository: Harry Ransom Center University of Texas at Austin Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Biographical Sketch Born September 11, 1917, in Batsford, Gloucestershire, England, Jessica Mitford is one of the six daughters of the Baron of Redesdale. The Mitfords are a well-known English family with a reputation for eccentricity. Of the Mitford sisters, Nancy achieved notoriety as a novelist and biographer. Diana married Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British fascists before World War II. Unity, also a fascist sympathizer, attempted suicide when Britain and Germany went to war. Deborah became the Duchess of Devonshire. Jessica, whose political bent ran opposite to that of her sisters, ran away to Loyalist Spain with her cousin, Esmond Romilly, during the Spanish Civil War. Jessica eventually married Romilly, who was killed during World War II. In 1943, Mitford married a labor lawyer, Robert Treuhaft, while working for the Office of Price Administration in Washington, D.C. The couple soon moved to Oakland, California, where they joined the Communist Party. In California, Mitford worked as executive secretary for the Civil Rights Congress and taught sociology at San Jose State University. -

Lipstick on the Pig Lipstick on The

ELECTION 2008 Lipstick on the Pig Robert David STEELE Vivas Public Intelligence Minuteman Prefaces from Senator Bernie Sanders (I‐VT), Tom Atlee, Thom Hartmann, & Sterling Seagraves Take a Good Look Our Political System Today Let’s Lose the Lipstick, Eat the Pig, and Move On! ELECTION 2008 Lipstick on the Pig Robert David STEELE Vivas Co‐Founder, Earth Intelligence Network Copyright © 2008, Earth Intelligence Network (EIN) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ EIN retains commercial and revenue rights. Authors retain other rights offered under copyright. Entire book and individual chapters free online at www.oss.net/PIG. WHAT THIS REALLY MEANS: 1. You can copy, print, share, and translate this work as long as you don’t make money on it. 2. If you want to make money on it, by all means, 20% to our non-profit and we are happy. 3. What really matters is to get this into the hands of as many citizens as possible. 4. Our web site in Sweden is robust, but you do us all a favor if you host a copy for your circle. Books available by the box of 20 at 50% off retail ($35.00). $20 is possible at any printer if you negotiate, we have to pay $35 with our retail discount, but actual cost to printer is $10. Published by Earth Intelligence Network October 2008 Post Office Box 369, Oakton, Virginia 22124 www.earth-intelligence.net Cover graphic is a composition created by Robert Steele using open art available on the Internet.