Page 1 of 5 Benjamin Spock Conspiracy 7/25/2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

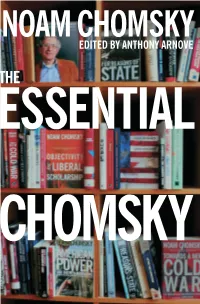

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael

South Carolina Law Review Volume 62 Issue 1 Article 2 Fall 2010 A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael Lonnie T. Brown Jr. University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lonnie T. Brown, Jr., A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Selective Non-Prosecution of Stokley Carmichael, 62 S. C. L. Rev. 1 (2010). This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brown: A Tale of Prosecutorial Indiscretion: Ramsey Clark and the Select A TALE OF PROSECUTORIAL INDISCRETION: RAMSEY CLARK AND THE SELECTIVE NON-PROSECUTION OF STOKELY CARMICHAEL LONNIE T. BROWN, JR.* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 II. THE PROTAGONISTS .................................................................................... 8 A. Ramsey Clark and His Civil Rights Pedigree ...................................... 8 B. Stokely Carmichael: "Hell no, we won't go!.................................. 11 III. RAMSEY CLARK'S REFUSAL TO PROSECUTE STOKELY CARMICHAEL ......... 18 A. Impetus Behind Callsfor Prosecution............................................... 18 B. Conspiracy to Incite a Riot.............................................................. -

Jessica Mitford

Jessica Mitford: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Title Jessica Mitford Papers Dates: 1949-1973 Extent 67 document boxes, 3 note card boxes, 7 galley files, 1 oversize folder (27 linear feet) Abstract: Correspondence, printed material, reports, notes, interviews, manuscripts, legal documents, and other materials represent Jessica Mitford's work on her three investigatory books and comprise the bulk of these papers. Language English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchase, 1973 Processed by Donald Firsching, Amanda McCallum, Jana Pellusch, 1990 Repository: Harry Ransom Center University of Texas at Austin Mitford, Jessica, 1917-1996 Biographical Sketch Born September 11, 1917, in Batsford, Gloucestershire, England, Jessica Mitford is one of the six daughters of the Baron of Redesdale. The Mitfords are a well-known English family with a reputation for eccentricity. Of the Mitford sisters, Nancy achieved notoriety as a novelist and biographer. Diana married Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British fascists before World War II. Unity, also a fascist sympathizer, attempted suicide when Britain and Germany went to war. Deborah became the Duchess of Devonshire. Jessica, whose political bent ran opposite to that of her sisters, ran away to Loyalist Spain with her cousin, Esmond Romilly, during the Spanish Civil War. Jessica eventually married Romilly, who was killed during World War II. In 1943, Mitford married a labor lawyer, Robert Treuhaft, while working for the Office of Price Administration in Washington, D.C. The couple soon moved to Oakland, California, where they joined the Communist Party. In California, Mitford worked as executive secretary for the Civil Rights Congress and taught sociology at San Jose State University. -

Vietnam War on Trial: the Court-Martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 1994 Vietnam War on Trial: The Court-Martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy Robert N. Strassfeld Case Western Reserve University - School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons Repository Citation Strassfeld, Robert N., "Vietnam War on Trial: The Court-Martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy" (1994). Faculty Publications. 551. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/551 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. TilE VIETNAM WAR ON TRIAL: TilE COURT-MARTIAL OF DR. HOWARD B. LEVY ROBERT N. STRASSFELD• This Article examines the history of a Vietnam War-era case: the court-martial of Dr. Howard B. Levy. The U.S. Army court-martialled Dr. Levy for refusing to teach medicine to Green Beret soldiers and for criticizing both the Green Berets and American involvement in Vietnam. Although the Supreme Court eventually upheld Levy's convicti on in Parkerv. Levy, ill decision obscures the political content of Levy's court-martial and its relationshipto the war. At the court-martialLe vy sought to defend himself by showing that his disparaging remarks about the Green Berets, identifying them as "killers of peasants and murderers of women and children," were true and that his refusal to teach medicine to Green Beret soldiers was dictated by medical ethics, given the ways in which the soldiers would misuse their medical knowledge. -

Benjamin Spock: a Two-Century Man

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 1996 Benjamin Spock: A Two-Century Man Bettye Caldwell Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Caldwell, Bettye "Benjamin Spock: A Two-Century Man," The Courier 1996:5-21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S YRAC U SE UN IVE RS I TY LIB RA RY ASS 0 CI ATE S COURIER VOLUME XXXI . 1996 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXI Benjamin Spock: A Two-Century Man By Bettye Caldwell, Professor ofPediatrics, 5 Child Development, and Education, University ofArkansas for Medical Sciences While reviewing Benjamin Spock's pediatric career, his social activism, and his personal life, Caldwell assesses the impact ofthis "giant ofthe twentieth century" who has helped us to "prepare for the twenty-first." The Magic Toy Shop ByJean Daugherty, Public Affairs Programmer, 23 WTVH, Syracuse The creator ofThe Magic Thy Shop, a long-running, local television show for children, tells how the show came about. Ernest Hemingway By ShirleyJackson 33 Introduction: ShirleyJackson on Ernest Hemingway: A Recovered Term Paper ByJohn W Crowley, Professor ofEnglish, Syracuse University For a 1940 English class at Syracuse University, ShirleyJackson wrote a paper on Ernest Hemingway. Crowley's description ofher world -

Vol. 1, No. 2 February 1968 Dr. Bejnarn1n Spock, Reverend William Sloane Coffin Jr., Marcus Raskin, Mitchell Goodman, and Michae

Vol. 1, No. 2 6324 Primrose Avenue February 1968 Los Angeles, Calif., 90028 Dr. Bejnarn1n Spock, Reverend William Sloane Coffin Jr., Marcus Raskin, Mitchell Goodman, and Michael Ferber were indicted on Friday, January 5, 1968, by the Rederal government on char~s of encouraging draft evasion. '!he following is a national staterrent that has been released in support of the five rren: "We stand beside the men who have been indicted for support of draft resistance. If they are sentenced, we too must be sentenced. If they are imprisoned, we will take their places and will continue to use what rreans we can to bring this war to an end. We will not stand by silently as our government conducts a criminal war. We will con tinue to offer support, as we have been doing, to those who refuse to serve in Viet Nam, to these indicted rren, and to all others who refuse to be passive accOl1'plices in war crimes. 'Ihe war is illegi timate and our actions are legitimate." Reverend Robert McAfee Brown Demise Leverton Noam Chcmsky IMight Macdonald Mary Clarke Herbert Magidson Reverend John Colburn Eason Monroe Reverend Stephen Fritchman Reverend William Moreman Paul Goodman Reverend Roy Ockert Florence Howe Ava Helen Pauling Professor Donald Kalish Professor Linus Pauling Louis Kampf Sidney Peck Reverend Martin Luther Ling, Jr. Hilary Putnam Lavid Krech Father Louis Vitale, O.F.M. Frederick Krews Arthur Waskow Reverend Tom Lasswell Reverend Harlan 1. Weitzel Paul Lauter Howard Zinn Reverend Speed Leas (Partial list of signers) I join in the above statement. -

On October 16, 1967, a Loosely-Knit Coalition Known As the Resistance Launched a Day National Day of Action Intended to Bring Th

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: A DISSIDENT BLUE BLOOD: REVEREND WILLIAM SLOANE COFFIN AND THE VIETNAM ANTIWAR MOVEMENT Benjamin Charles Krueger, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Dissertation Directed By: Professor Robert N. Gaines Department of Communication A long and bloody conflict, United States military action in Vietnam tore the fabric of American political and social life during the 1960s and 1970s. A wide coalition of activists opposed the war on political and religious grounds, arguing the American military campaign and the conscription of soldiers to be immoral. The Reverend William Sloane Coffin Jr., an ordained Presbyterian minister and chaplain at Yale University, emerged as a leader of religious antiwar activists. This project explores the evolution of Coffin’s antiwar rhetoric between the years 1962 and 1973. I argue that Coffin relied on three modes of rhetoric to justify his opposition to the war. In the prophetic mode, which dominated Coffin’s discourse in 1966, Coffin relied on the tradition of Hebraic prophecy to warn that the United States was straying from its values and that undesirable consequences would occur as a result. After seeing little change to the direction of U.S. foreign policy, Coffin shifted to an existential mode of rhetoric in early 1967. The existential mode urged draft-age men to not cooperate with the Federal Selective Service System, and to accept any consequences that occurred as a result. Federal prosecutors indicted Coffin and four other antiwar activists in January 1968 for conspiracy aid and abet draft resister in violation of the Selective Service Act. Chastened by his prosecution and subsequent conviction, Coffin adopted a reconciling mode of discourse that sought to reintegrate antiwar protesters into American society by advocating for amnesty. -

Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: the Ep Rilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2007 Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The eP rilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The eP rilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms, 2 London Law Review 2 (2007) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. bepress Legal Series Year Paper Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The Perilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Kenneth Lasson University of Baltimore This working paper is hosted by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress) and may not be commercially reproduced without the permission of the copyright holder. http://law.bepress.com/expresso/eps/1090 Copyright c 2006 by the author. Civil Liberties in Uncivil Times: The Perilous Quest to Preserve American Freedoms Abstract The perilous quest to preserve civil liberties in uncivil times is not an easy one, but the wisdom of Benjamin Franklin should remain a beacon: “Societies that trade liberty for security end often with neither.” Part I of this article is a brief history of civil liberties in America during past conflicts. -

FREEDOM of EXPRESSION in WARTIME " Thomas I

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN WARTIME " THomAs I. EMERSON t War and preparation for war create serious strains on a system of freedom of expression. Emotions run high, lowering the degree of rationality which is required to make such a system viable. It becomes more difficult to hold the rough give-and-take of controlled controversy within constructive bounds. Immediate events assume greater importance; long-range considerations are pushed to the back- ground. The need for consensus appears more urgent in the context of dealing with hostile outsiders. Cleavage seems to be more dan- gerous, and dissent more difficult to distinguish from actual aid to the enemy. In this volatile area the constitutional guarantee of free and open discussion is put to its most severe test. It is not surprising, therefore, that throughout our history periods of war tension have been marked by serious infringements on freedom of expression. The most violent attacks upon the right to free speech occurred in the years of the Alien and Sedition Acts, the approach to the Civil War, the Civil War itself, and World War I-all times of war or near-war.1 Yet it was not until the end of World War I that judicial application of the first amendment played any significant role in these events. Up to this point there had been no major decision by the Supreme Court applying the guarantees of the first amendment. Then, in 1919, the Court issued the first of a series of decisions dealing with federal and state legislation that had been enacted to restrict free expression during the war, and thus began the long development of first amendment doctrine. -

Red and White on the Silver Screen: the Shifting Meaning and Use of American Indians in Hollywood Films from the 1930S to the 1970S

RED AND WHITE ON THE SILVER SCREEN: THE SHIFTING MEANING AND USE OF AMERICAN INDIANS IN HOLLYWOOD FILMS FROM THE 1930s TO THE 1970s a dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bryan W. Kvet May, 2016 (c) Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Dissertation Written by Bryan W. Kvet B.A., Grove City College, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 1998 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ___Kenneth Bindas_______________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Kenneth Bindas ___Clarence Wunderlin ___________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Clarence Wunderlin ___James Seelye_________________, Dr. James Seelye ___Bob Batchelor________________, Dr. Bob Batchelor ___Paul Haridakis________________, Dr. Paul Haridakis Accepted by ___Kenneth Bindas_______________, Chair, Department of History Dr. Kenneth Bindas ___James L. Blank________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. James L. Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………iv LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...vii CHAPTERS Introduction………………………………………………………………………1 Part I: 1930 - 1945 1. "You Haven't Seen Any Indians Yet:" Hollywood's Bloodthirsty Savages……………………………………….26 2. "Don't You Realize this Is a New Empire?" Hollywood's Noble Savages……………………………………………...72 Epilogue for Part I………………………………………………………………..121 Part II: 1945 - 1960 3. "Small Warrior Should Have Father:" The Cold War Family in American Indian Films………………………...136 4. "In a Hundred Years it Might've Worked:" American Indian Films and Civil Rights………………………………....185 Epilogue for Part II……………………………………………………………….244 Part III, 1960 - 1970 5. "If Things Keep Trying to Live, the White Man Will Rub Them Out:" The American Indian Film and the Counterculture………………………260 6. -

Algeria, Vietnam, Iraq and the Conscience of the Intellectual

Volume 4 | Issue 2 | Article ID 1995 | Feb 16, 2006 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Algeria, Vietnam, Iraq and the Conscience of the Intellectual Lawrence S. Wittner Algeria, Vietnam, Iraq and the Conscience ideas in some fashion, often applying ideas in of the Intellectual an ethical way that may question the legitimacy of the established authorities." Thus, "a By Lawrence S. Wittner significant percentage of the professoriate and some journalists" can be classified as intellectuals, as can "a substantial portion of "History," the French philosopher Julien Benda the artistic community . who theorize in print once remarked, "is made from shreds of justice about their creativity." In his view, "there was, that the intellectual has torn from theand perhaps remains, a symbiotic relationship politician." This contention may overestimate between the intellectual and engagement," a the power of the former and underestimate the French term meaning "critical dissent." power of the latter. But it does point to a tension between intellectuals and government Schalk argues convincingly that there were officials that has existed at crucial historical remarkable similarities between the Algerian junctures--for example, in late nineteenth and Vietnam wars. These include: the use of century France (where the term "intellectual torture; the looming precedent of the was first coined in connection with the Dreyfus Nuremberg trials; anti-colonial revolt; the affair) and in the late twentieth century Soviet undermining of democracy; the murky style -

A CALL to RESIST ILLEGITIMATE AUTHORITY to the Young Men of America, to the Whole of the American People, and to All Men of Good Will Everywhere

MA,„to 00 'b } A CALL TO RESIST ILLEGITIMATE AUTHORITY To the young men of America, to the whole of the American people, and to all men of good will everywhere: An ever growing number of young American men are ter of peasants who dared to stand up in their fields and I• finding that the American war in Vietnam so outrages shake their fists at American helicopters; — these are all their deepest moral and religious sense that they cannot actions of the kind which the United States and the other contribute to it in any way. We share their moral outrage. victorious powers of World War II declared to be crimes against humanity for which individuals were to be held We further believe that the war is unconstitutional personally responsible even when acting under the orders 2• and illegal. Congress has not declared a war as re of their governments and for which Germans were sen quired by the Constitution. Moreover, under the Constitu tenced at Nuremberg to long prison terms and death. The tion, treaties signed by the President and ratified by the prohibition of such acts as war crimes was incorporated in Senate have the same force as the Constitution itself. The treaty law by the Geneva Conventions of 1949, ratified by Charter of the United Nations is such a treaty. The Charter the United States. These are commitments to other countries specifically obligates the United States to refrain from force and to Mankind, and they would claim our allegiance even or the threat of force in international relations.